#the twenties

Card for Magic the Gathering: “Streets of New Capenna”

Basic Land - Plains

I was so excited to create several cards for the new Art Deco setting Magic the Gathering.

Post link

Rare card for Magic the Gathering: “Streets of New Capenna”

My very first card for MTG. Cabaretti in all their glory.

Post link

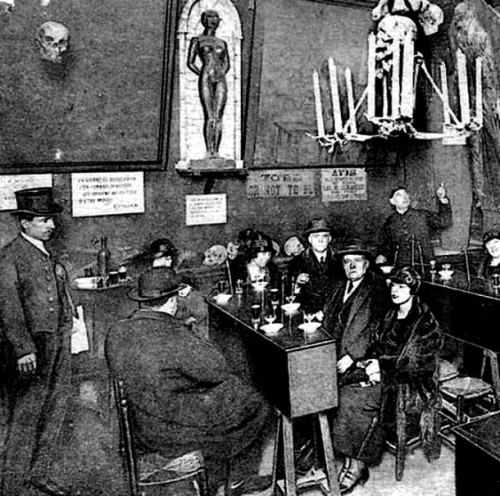

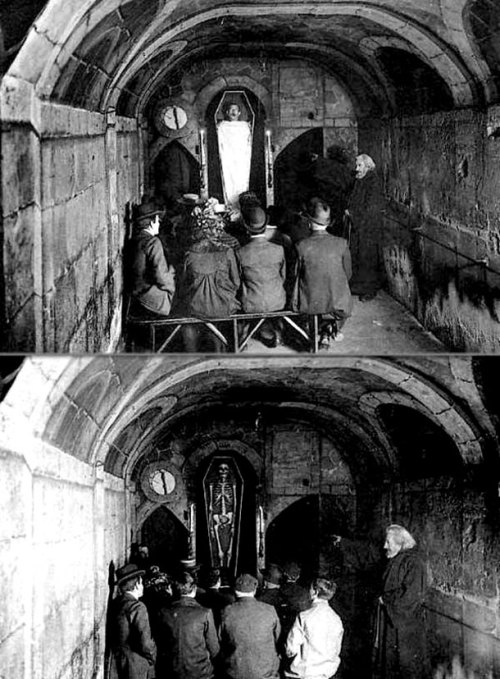

Paris nightclub, 1920s.

https://www.mixcloud.com/20thcenturynostalgia/let-us-scare-your-children/

Post link

fromMotion Picture Classic, April 1922

Transcription:

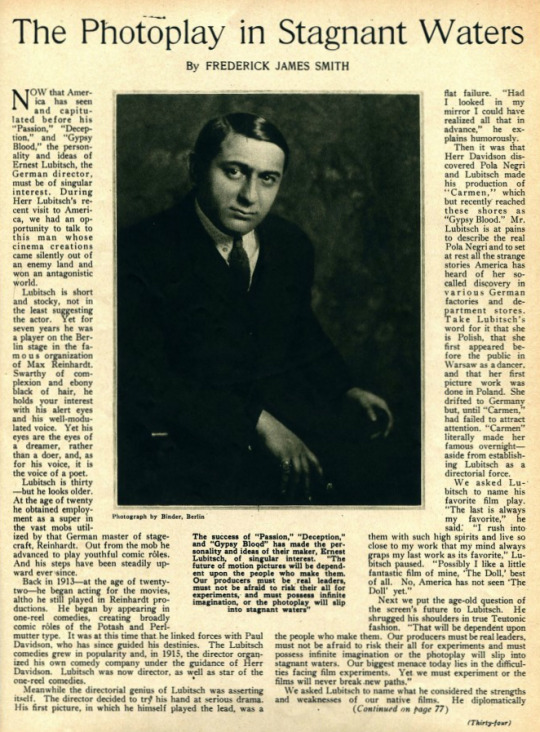

NOW that America has seen and capitulated before his “Passion,” “Deception,” and “Gypsy Blood,” the personality and ideas of Ernest [sic] Lubitsch, the German director, must be of singular interest. During Herr Lubitsch’s recent visit to America, we had an opportunity to talk to this man whose cinema creations came silently out of an enemy land and won an antagonistic world.

Lubitsch is short and stocky, not in the least suggesting the actor. Yet for seven years he was a player on the Berlin stage in the famous organization of Max Reinhardt. Swarthy of complexion and ebony black of hair, he holds your interest with his alert eyes and his well-modulated voice. Yet his eyes are the eyes of a dreamer, rather than a doer, and, as for his voice, it is the voice of a poet.

Lubitsch is thirty—but he looks older. At the age of twenty he obtained employment as a super in the vast mobs utilized by that German master of stagecraft, Reinhardt. Out from the mob he advanced to play youthful comic rôles. And his steps have been steadily upward ever since.

Back in 1913—at the age of twenty-two—he began acting for the movies, altho he still played in Reinhardt productions. He began by appearing in one-reel comedies, creating broadly comic rôles of the Potash and Perlmutter type. It was at this time that he linked forces with Paul Davidson, who has since guided his destinies. The Lubitsch comedies grew in popularity and, in 1915, the director organized his own comedy company under the guidance of Herr Davidson. Lubitsch was now director, as well as star of the one-reel comedies.

Meanwhile the directorial genius of Lubitsch was asserting itself. The director decided to try his hand at serious drama. His first picture, in which he himself played the lead, was a flat failure. “Had I looked in my mirror I could have realized all that in advance,” he explains humorously.

Then it was that Herr Davidson discovered Pola Negri and Lubitsch made his production of “Carmen,” which but recently reached these shores as “Gypsy Blood.” Mr. Lubitsch is at pains to describe the real Pola Negri and to set at rest all the strange stories America has heard of her so-called discovery in various German factories and department stores. Take Lubitsch’s word for it that she is Polish, that she first appeared before the public in Warsaw as a dancer, and that her first picture work was done in Poland. She drifted to Germany but until “Carmen,” had failed to attract attention. “Carmen” literally made her famous overnight—aside from establishing Lubitsch as a directorial force.

We asked Lubitsch to name his favorite film play. “The last is always my favorite,” he said: “I rush into them with such high spirits and live so close to my work that my mind always graps [sic] my last work as its favorite,” Lubitsch paused. “Possibly I like a little fantastic film of mine, ‘The Doll,’ best of all. No, America has not seen ‘The Doll’ yet.”

Next we put the age-old question of the screen’s future to Lubitsch. He shrugged his shoulders in true Teutonic fashion. “That will be dependent upon the people who make them. Our producers must be real leaders, must not be afraid to risk their all for experiments and must possess infinite imagination or the photoplay will slip into stagnant waters. Our biggest menace today lies in the difficulties facing film experiments. Yet we must experiment or the films will never break new paths.”

We asked Lubitsch to name what he considered the strengths and weaknesses of our native films. He diplomatically

(Continued on page 77)

Photo Caption:

The success of “Passion,” “Deception,” and “Gypsy Blood” has made the personality and ideas of their maker, Ernest [sic] Lubitsch, of singular interest. “The future of motion pictures will be dependent upon the people who make them. Our producers must be real leaders, must not be afraid to risk their all for experiments, and must possess infinite imagination, or the photoplay will slip into stagnant waters”

The Photoplay in Stagnant Waters

(Continued from page 34)

professed to have seen but few of them. One however, he named with genuine enthusiasm. It was Griffith’s “Broken Blossoms.” “That is a true work of art,” he said. And he enthused over the work of Charlie Chaplin. We asked him to name the foremost American film players and he again lapsed into diplomatic silence. But when we asked him to select that foremost film player of Europe, his eyes lighted and he named Pola Negri without a second’s hesitation. And he listed Emil Jannings, Paul Wegener and Weiner [sic] Krauss as among the foremost celluloid actors. Incidentally, Lubitsch confirmed the report that Jannings, the unforgettable Louis XV of “Passion” and Henry VIII of “Deception,” is of American blood. Jannings is of American parentage, altho he was born in Switzerland.

Lubitsch briefly explained his method of work, which differs but little from those of our own directors. Save in one important particular. Before starting a production, he goes away with his scenario editor and together they devote a month to working out the continuity.

Here Lubitsch pointed out that European continuity differs from American in one essential aspect. Motion pictures in Germany, Italy and Sweden are shown after the style of spoken plays—in acts, usually four in number, with intermissions between the parts. This necessitates building to act climaxes, after the fashion of the footlight drama. Lubitsch declares this to be easier than the American continuity, which must steadily build upward until it reaches its climax.

“My actual methods of direction are, I suppose, similar to American ways. I have but one fixed rule: I never use players until I know their personalities and real inner selves. In that way, I never ask more of them than they can give.”

Lubitsch looks but lightly upon the present film depression. “A war reaction,” he explains. “During the struggle the people of every country had more or less excess money to spend. And they had to do something steadily to forget. So even film rubbish attracted, for the war-time audiences sought only amusement.

“Now conditions are different. Money is scarce. People have no horror to forget. They think before entering a theater and they sit with a critical attitude. All over Europe conditions are psychologically the same as in America.”

Lubitsch laughs at the idea of German motion pictures injuring American film making. “We must interchange—for we all need the best products of every country. Never forget that the photoplay is international and that the people of every land are essentially the same in every way. And do not forget that the photoplay is the one art speaking all languages.”

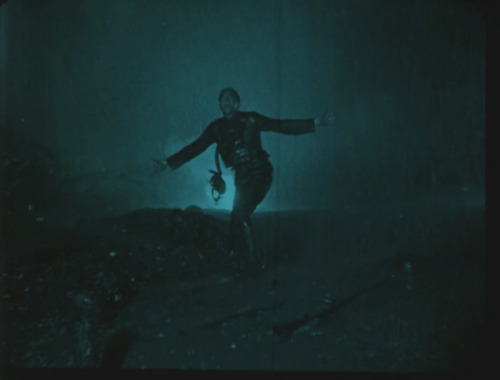

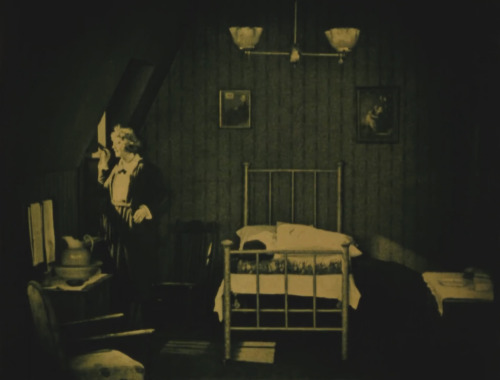

1922 in 2022: Back Pay(1922)

Directed by Frank Borzage

Adapted for the screen by Frances Marion

Based on a story by Fannie Hurst

Photographed by Chester Lyons

Produced by Cosmopolitan Productions

Premiered on 8 January 1922

Synopsis:

Hester Bevins (Seena Owen) dreams of a bigger, more extravagant life than her small-town home of Demopolis can offer. When Hester decries her flannel and gingham lifestyle to her beau, Jerry (Matt Moore), he doesn’t take her seriously. Regardless, once Hester has the scratch, she moves to New York City. There, she toils in obscurity for a few years before she lands a tycoon boyfriend, Wheeler (J. Barney Sherry). Though Hester has settled into the lap of luxury, she hasn’t forgotten her roots. Hester returns to Demopolis for a spell while on a road trip with Wheeler and friends. There she finds the whole town has forgotten her, except for Jerry. Jerry still insists Hester belongs in gingham and with a heavy heart she rejects him again and returns to the city. Normal life resumes for Hester, while Jerry enlists to fight in World War I. After Hester discovers that Jerry has returned to the States wounded, she rushes to the hospital and is informed that he only has three weeks to live. Hester thinks up a scheme to make the most of his last days by marrying him and convincing the now-blind Jerry that she’s living in a humble one-room apartment on earnest wages. She easily gains Wheeler’s agreement to support this arrangement. The pair live out an imitation of Jerry’s modest domestic fantasy until Jerry’s death. Hester unexpectedly finds that she is unable to return to her former life. Hester is haunted by the spectre of Jerry and feels guilty for her ruse. After her maid foils an attempted suicide, Hester resolves to become the person Jerry believed she was. Hester moves into a dingy one-room apartment, reclaims her old job, and is determined to pay for Jerry’s funeral with money she earned “honestly” as a final act of atonement.

My Impressions:

There was a lot I liked about this movie, and I really enjoyed Seena Owen’s performance, but the morality of the story was so shallow that it left me frustrated.

There’s not much information online about the movie, so I tried to scan through movie magazines from the time with little luck. Then I ended up finding a contemporary review cited on Back Pay’s Wikipedia page! The reviewer, James W. Dean, was also disenchanted with the hollowness of the film. Dean was already familiar with the story from the original publication (in Cosmopolitan Magazine in 1921) and from the stage play which was running while Back Pay was produced and released. And, according to Dean, the movie adaptation gutted the substance of the story. This spurred me on to find a copy of the original story and golly was Dean right!

In the story, Hester’s childhood in Demopolis is recounted in a way that deeply informs the choices she makes as an adult. Hester was raised by a protective aunt who also happened to be running an adult establishment out of her home. These childhood experiences shape Hester’s view of men and her expectations of life. This also frames Demopolis as less of a sleepy, idyllic bit of Americana. The film contains no hint of Hester’s life before the plot commences.

The film also whittles down the character of Wheeler, who in the story has a wife and child he’s double timing. He’s also searingly referred to as a “parlor patriot.” As the war rages abroad, Wheeler is specifically described as a war profiteer. When Hester asks him to do a solid for a disabled veteran, she even mentions that it’s only right seeing how much money he’s made off the war!

There isn’t much different about Jerry between the two versions of the story, aside from some blatant anti-Semitism is the original story. Honestly, even with the bigotry removed, I found it hard to like a character whose main trait is invalidating his girlfriend’s self image.

While the original story also tackles morality and guilt, the added depth of Hester’s psychology and the added shittiness of Wheeler make for a much more dynamic story.

So, I’ve ragged a lot on what was removed from “Back Pay” when it was adapted for the screen, but there is one addition that stuck with me. It regards Hester’s live-in maid. The maid isn’t a full character in either version of the story. But, if you remember from the synopsis, after the maid saves Hester’s life, Hester decides to up and leave. In other words, Hester abandons this very loyal woman in the early hours of the morning, leaving her potentially homeless and jobless with absolutely no prior notice. But, seemingly Borzage had some awareness of how completely insensitive this act was, because the camera lingers on the (unfortunately uncredited) maid looking anxious and despondent after Hester’s departure. This minimal moment is more thought given to that character than the original story, shockingly.

The aforementioned shot of the tragically uncredited maid.

Further Info: [below the jump!]

- Adjusted for inflation, the chinchilla coat that Hester wants Wheeler to buy for her would be $368,170.00 in 2022 dollars. Jerry’s funeral costs would be $8,848.63. (Although the movie is set some time in the 1910s, not 1922 so the numbers would be slightly different in actuality.)

- Back Pay was produced by Cosmopolitan Productions, which was owned by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. The business model of Cosmopolitan was that it would have the film rights to the popular stories that ran in Hearst’s magazines and would also be able to promote the films in Hearst-owned publications. At the time Back Pay was made, Cosmopolitan’s films were distributed through Paramount.

- Back Pay was shot at Cosmopolitan’s New York studio located at Harlem River Park. The area used to contain an amusement park and casino. However, a year after Back Pay was released, while production ofLittle Old New York(1923) with Marion Davies was under way, the studio burned down. This precipitated the studio moving production to California.

Photo of Cosmopolitan’s studio c. 1923 from the HABG Task Force website.

The city block where the studio once stood (between 1st & 2nd and E 126th & E 127th in Harlem) was, until recently, a city bus depot abutting a bridge ramp. We often talk about how much has changed in Hollywood in the last century, but the old movie-making enclaves in New York and New Jersey have also changed massively! I bet the view across the river from the studio was lovely back then!

The block as seen on Google Maps in 2019. (Shoutout to this dude in a Dragon Ball Z t-shirt btw)

Seeing as this post is already a beast, I’ll quickly say that the history of this location, going all the way back to when Harlem was still Nieuw Harlem is fascinating and the redevelopment plans for the area sound great! The website Urban Archive has a full survey. It’s worth a read!

You can also check out the HABG Task Force website for details on the redevelopment, which is currently slated to be completed in 2023.

Post link

from Motion Picture Magazine, January 1922

Photo Caption: “The winner of the contest is Miss Clara Bow, of 875 Seventy-third Street, Brooklyn, New York. She is very young, only sixteen. But she is full of confidence, determination and ambition. She screens perfectly, Above, a new portrait of Miss Bow.”

The New Star

“The great Contest is closed. The winner is chosen. These two short sentences might tell it all, representing as they do, nearly a year of hopes and disappointments for the thousands of contestants.

The winner is Miss Clara Bow, 857 73rd Street, Brooklyn, New York. She is very young, only sixteen. But she is full of confidence, determination and ambition. She is endowed with a mentality far beyond her years. She has a genuine spark of the divine fire. The five different screen tests she had, showed this very plainly, her emotional range of expression provoking a fine enthusiasm from every contest judge who saw the tests. She screens perfectly.

Her personal appearance is almost enough to carry her to success without the aid of the brains she indubitably possesses. She has short blonde curly hair, very thick. Her eyes are big and brown and set far apart in compliance with a law of beauty. Her features are delicate, the mouth particularly lovely. Her teeth are even and white, and her suite is as gay and unforced as youth itself. She is slenderly built, with an easy and graceful carriage, that proclaims perfect health and a freedom and zest, denied those of more mature years.

The distinguished contest judges are well satisfied with their decision.”

FULL TRANSCRIPTION BELOW:

“MOTION PICTURE MAGAZINE is glad also, to publish the Final Honor Roll. It consists of those who were considered for the final winner. Several of them were very strong contenders, but individually they lacked the various good points that made Miss Bow the final choice. We are sorry to note that only one male entry is included. The Final Honor Roll is as follows:

Miss Clara Bow, 857 73rd Street, Brooklyn, New York.

Miss Eilleen Eliott, 1707 Ritner Street, Philadelphia, Pa.

Miss Laura Lyle, 56 W. 47th Street, New York City.

Miss Ella Lee Jeannette Ruby, 838 N. Church Street, Rockford, Ill.

Miss Margaret Porter, 1078 Madison Avenue, New York City.

Miss Helene Bristow, 105 Thomas Street, Newark, N.J.

Miss Bojan Claussen, 129 W. 87th Street, New York City.

Mr. Maurice Kaines, 11 Abingdon Sq. New York City.

(Continued on page 99)

The New Star

(Continued from page 55)

“Miss Virginia Eastman, 104 West Seventieth Street, New York City.

Miss Lula M. Hubbard, 223 Fourth Street, San Antonio, Texas.

Other Awards in the contest were three very beautiful pieces of lace, which Ensign Tyburc, of the United States Navy, brought from abroad for the express purpose of giving them to the Fame and Fortune Contest. The lace was made by the nuns on the islands of Malta, famous the world over for their exquisite laces.

Miss Bow was given a little bolero jacket. Miss Eastman was presented with a filmy scarf. Miss Ursula Mengoni, a little girl just five years old, had a pair of unusual lace socks for her baby feet, given to her, as her share of the contest glory.

MOTION PICTURE MAGAZINE is glad to present Miss Bow’s sincere and grateful letter in full:

‘Gentlemen: I want to thank all those in the Brewster Publications, Inc., who have been responsible for the kind treatment and many efforts on my behalf, from the day of my entrance into the Fame and Fortune Contest of 1921 up until the present time, and also for the beautiful outfit, which they so kindly presented me with. Everyone thinks the outfit beautiful, and is so very becoming, thanks to the taste of Mrs. Gleason and Miss Palmer.

‘Now, about my future. I hope that everything you credit me with will prove true, and that all your hopes and expectations will also do the same. I hope that with the proper training I will grow into a good actress, worthy of the Brewster Publications’ help, and hope that some day Mr. Brewster and the rest will be proud of me and my work. I intend to work very hard and try and perform the smallest role that is given to me to the best of my ability.

‘I thought that writing to you would be better than trying to get an interview. In any business matters, I hope to rely upon your judgment, as I am inexperienced in that direction.

‘Feeling that I have said all I wish to say, I will close, with much appreciation and thanks to the Brewster Publications, Inc. I am, Yours sincerely,

‘Clara G. Bow.’”

Post link