#adventure log

There was no Adventure Log last week because I spent the entire week ploughing through a huge pile of essays. As compensation, this week I have hired a professional. Sit back and relax as urbanAnchorite and I take you on a tour of the early-90s edutainment software ‘scene’, a scene which turns out to have had a greater influence on both of us than previously suspected.

Below the cut: Granny’s Garden, Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood, L: A Mathemagical Adventure, Stickybear Math Town, Hazard/Rescue, Treasure Mountain!, and a couple of runners-up.

GRANNY’S GARDEN (BBC/ACORN, 1983)

pT: Granny’s Garden 'served as a first introduction to computers for many schoolchildren in the United Kingdom during the 1980s and 1990s’, saith Wikipedia. Yes. It also served as a first introduction to fear.

A strange thing about being five years old is that extremely rudimentary puzzles are still the Voynich fucking Manuscript. Because your gelatinous, ill-knit brain hasn’t yet wrapped round the entire concept of ‘puzzles’ as an artificial but entertaining challenge created for you by another human person, they remain this mystical intrusion from Beyond, this horrifying glimpse of the vast enigma that you know lurks just below the world’s skin despite your parents’ best attempts to convince you otherwise. Who had made Granny’s Garden? What was it for? How had it come to be on this innocuous wafer of blue plastic in our teacher’s classroom, and why was our teacher letting us study it? Didn’t she realise?

My memories of this game are so stained with terror and fascination that they border on the hallucinatory. Here is a puzzle from Granny’s Garden:

Before we can go in you must solve a little puzzle:

There is a secret word on the house. What is it?

It’s FIG. I’m just going to spoil that for you. The secret word on the house is FIG. Furthermore, it is always FIG. Procedural world generation, in 1983, was still a way off. You could play the game a thousand times and the word would always be FIG. And yet, I very clearly remember being gathered round an RM Nimbus in the St Mary’s RC Primary 'computer room’ with like five other children, all hunched forward, intent on the screen, when whoever had the keyboard hit this puzzle. Someone - it might have been me - said 'It’s FIG’, in the tones of a veteran in the dugout grimly passing on to the cowering rookies that that was a phosphorus shell going off. And then I’m pretty sure they said 'I’ve seen this before’.

You have to understand: this wasn’t one smug kid showing off their knowledge to the other kids. This was survival. Everyone else was mute with relief to have such a well-travelled guide. No-one in the school had ever escaped from Granny’s Garden. It was a six-man raid and every other party had wiped. If we were going to make it out, we needed to work as a team. And now we were through the secret word puzzle, sure, but what horrors lay inside?

The game is violently arbitrary, which again feeds into one’s childhood assumptions about the world. Some things you can do are bad. You don’t know why. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with them. But if you do them, you were wrong, and will die. Once you get into the woodcutter’s house, you can go into the kitchen, but if you look in the cauldron, you get an instantaneous Game Over. You can look in the cupboard under the stairs, where you’ll find a red broom. If you take it, Game Over. (Please admire that for a second. Almost every point-and-click adventure game ever made operates on the axiom that if you find a random object lying around, and it’s not obviously something you shouldn’t be taking, like the key to the treasure room, you should pick it up. In Granny’s Garden, the first random object you find kills you.) There’s a long stick you can take, too, which doesn’t harm you at all - unless when you meet a snake, upstairs, you try to use the stick on it. If you do that, Game Over. Because the stick was actually a booby-trapped magic wand, specifically placed by her.

And there she is. The Face of Evil. A Game Over in Granny’s Garden has no preamble. Suddenly, the screen changes and she's there. You can’t run, you can’t fight. She will send you home at once. (space bar)

(No, being sent home is not actually that bad. In my adult life, there are many days during which I actively long to be sent home at once. Sometimes I open cupboards and pick up random brooms, and then say, hopefully, 'oh whoops, I have picked up this broom’. But as a five-year-old, you know perfectly well that 'send you home at once’ is witcholese for 'crunch your bones between my hooked cyan mandibles’, and so you are terrified as shit, let me tell you.)

Because the woodcutter’s house is the first area of the game, I remember it much more clearly; in many runs it was as far as we got. (Kid memories aren’t great for this kind of thing, so if you’re playing the game again a week later, you’re like: wait, picking up the red broom turned out to be a good idea, right? Pretty sure, yeah.) The next part involved making your way across a garden with the help of some insects. The part after that definitely involved giving dragons their favourite foods in order to tame them, and was famously hard. There was one more area after that, but the dragon puzzle was so vicious that almost nobody ever saw it. I think there was a map.

Granny’s Garden was basically Amnesia: The Dark Descent for 1990. The solemnity with which we gathered round the Nimbus for another doomed attempt to free Esther, Tom, and the other pixellated children from the witch’s clutches was almost sacramental. The acid-coloured text on the pitch-black screen gave the game a weird horror ambience, subtly (if untentionally) reinforced by the writing. Look again up there: before we go in you must solve a little puzzle. I think that’s meant to sound sort of fairy-tale and reassuring, but the sugary diminutive of 'little’ - just a little puzzle, nothing that could hurt - alongside the blunt imperative of 'must’ produces a genuinely sinister effect. If they’d said: there’s a secret word on the house! Can you work out what it is?, that would have sounded kind of exciting, like a fun challenge for you to test yourself against. You must solve a little puzzle is what Jigsaw tells you before he takes off your blindfold. If you picked up the red broom the game crowed Silly! Silly! Silly! in bright green text, giving you just a second to realise that she was behind you.

And, I mean. It was a cupboard. Why… why was it very cold in there?

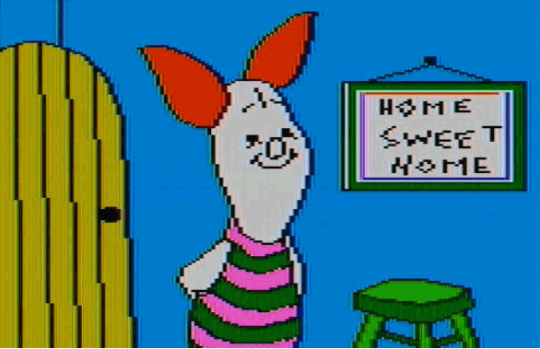

WINNIE THE POOH IN THE HUNDRED ACRE WOOD (AMIGA/COMMODORE, 1986)

uA: I began playing Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood around age four. It was a randomised find-the-item game where familiar objects from Winnie the Pooh (Eeyore’s tail, Rabbit’s carrot) and return them to their owners.

It is also the Zork of edutainment and may be responsible for my career in horror, because it depicts the Hundred Acre Wood as unfailingly lonely and empty, the kind of place where the body is buried. Every so often you’ll randomly encounter Tigger and he’ll “bounce” you, making you drop all the items you’ve so carefully collected and scattering them to the four winds. This felt not unakin to getting stalked by Walter Sullivan in Silent Hill 4: The Room.

Also everyone looked just slightly off, like this:

And the game let you perform unreal meta self-reflection, like this:

And also asked you to believe

Whoooo put Bella in the wych elm

The game also let you watch it render itself in real time, so that with every screen you waited as you watched the lines draw and the colours fill – a common thing at the time, this was early Amiga – but this also had the curious result that the Hundred Acre Wood unmade and re-made itself around you as you moved through it, just like in Darkwood. The graphics themselves were also dilated in a weird way – tunnels were enormous, holes were voids, trees stretched into space – which, for a child raised entirely on the American-style Winnie the Pooh cartoon seemed distinctly unfriendly and freakish.

You could finish the game and have a party with your uncanny valley buds and Christopher Robin, but usually I’d fled the room in tears by that point.

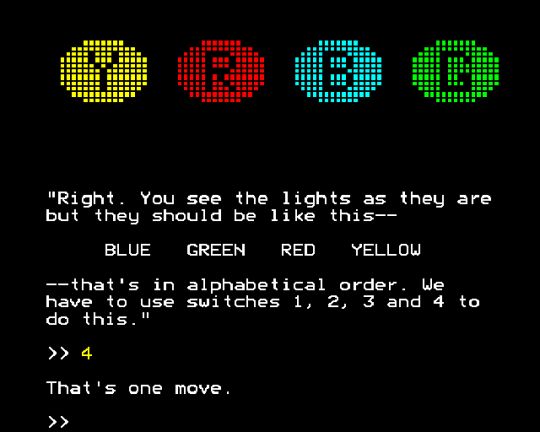

L: A MATHEMAGICAL ADVENTURE (BBC/ACORN, 1984)

pT: IfGranny’s Garden was my five-year-old self's Clock Tower, the weirdly-named L was my Myst (although it was supplanted in my affections by the actual Myst not that long afterwards). It was an old-school parser IF game written by a team of UK maths teachers (oh yes), which I suppose was meant to introduce you to exciting maths concepts, but mostly just induced a dreamlike state of dissociation from reality while forcing you to meander in circles. It has a tremendous opening page:

It is a very hot day. You are sitting on the grass outside a crumbling palace. Your sister is reading a book called “Fractions and the Four Rules - 5000 Carefully Graded Problems”. You are bored and the heat is making you feel a little sleepy. Suddenly you see an old man dressed as an abbot. He glances at you nervously and disappears through a small door in the side of the palace.

'Dressed as an abbot’ there is incredible. It would have been so easy to say 'dressed as a monk’, which is approximately five times less intriguing. Also, I think 'You are sitting on the grass outside a crumbling palace’ may be some of the most vestigial yet effective scene-setting I’ve ever encountered. What palace? Whose palace? Why are you just chilling outside it? Why is it crumbling? Palaces, in the main, don’t crumble. Castles crumble; palaces are kept in tip-top condition. If I can ever write an opening sentence that good, I’ll be happy.

Anyway, you follow the spurious abbot (or maybe he’s a real abbot - even real abbots are, technically, dressed as abbots) in through the side door because you know a quest hook when you see one and your sister is clearly a pill, and then you get totally lost in a big, empty building full of puzzles. Unlike Granny’s Garden, most people at my school ignored L - it had a reputation for being impossible - and I think I was one of the only kids who ever took the disk out of the box. I found it fascinating, even though I don’t think I ever got even a quarter of the way into it. You could find models of the Platonic solids, made of expensive luxury materials, just kind of lying around enigmatically: 'You are in the ballroom. You see an ivory icosahedron.’ My Mum had to explain to me that they were Platonic solids, which at least was a teaching moment. I assume that eventually there’d have been some kind of metapuzzle where you’d need to use all five Platonic solids to do something, but I never got that far, so I just wandered around the palace with a clanking satchel of looted abstract art, looking at the sunbeams.

There was a puzzle where you had to combine spotlight colours, which I solved, and one with a boat, which I could never seem to get past. I don’t know if it was really hard, or if I was just too young for it. But I still think about that crumbling palace, sometimes. Presumably my sister is still sitting on the lawn waiting for me to emerge. I wonder if she’s run out of problems yet.

STICKYBEAR MATH TOWN ET AL. (APPLE II, 1985 ONWARDS)

uA: Despite the name, Stickybear was a bear whose tailor told him suits were meant to fit that way.

Stickybear would attempt to teach me typing, shapes and “math”, but patently fucking failed.

The Stickybear adventure I recall most vividly was Stickybear Math Town, in which the eponymous Stickybear does a variety of maths activities that seemed unnecessary to me at the time: for instance, every trip to the grocery involved long division. I guess that’s how life treated you in Math Town.

I have never lived in Math Town. I would go weekly to Kip McGrath, the local NZ tutelage jail, in an optimistic attempt to get my maths up to passing School Cert. I remember Stickybear Math Town as little more than an Anathem-style parade of impossible cake calculations. Humiliatingly, keep in mind that it was the early noughties and that I was fifteen. Stickybear sometimes had to catch fruit that rained from the sky in order to get his hundreds, tens and ones in order, and I remember getting quite good at that, though not good enough to get more than 45% for my fifth-form qualification.

I only found out this hot second that Stickybear Math Town was for children with learning disabilities, so my whole life just got rudely explained, I guess.

I think I have dyscalculia, Stickybear.

HAZARD/RESCUE (BBC/ACORN, ????)

pT: I want to start this with a heartfelt appeal: if anyone out there on the Internet has any idea how I could get my hands on a copy of Hazard/Rescue, please, please let me know. Of all the games I’ve ever played, it’s the one I’d most like to play again, and yet no-one seems even to remember it existed. I sometimes feel that creeping sense of Candle Cove about it.

Hazard/Rescue was a very early game making program. It was actually two halves, hence the weird name. Hazard let you construct a very basic text adventure to your own specifications. You could lay out rooms on a map, and then fit them out with either items or obstacles. Each obstacle required a specific item to get past. So: 'You are in the BONDAGE DUNGEON. There is a MALFUNCTIONING SEX DROID here. Do you have the ROCKET LAUNCHER?’. If you didn’t, you had to go and explore somewhere else to try and find the rocket launcher so you could keep going. But all of the flavour text - the names of the rooms, their descriptions, the obstacles and the items - you could fill in yourself. Then you could save the game as a file, switch over to Rescue, and play it - or get your friend to.

I hardly ever got time to play Hazard/Rescue, but I planned so many games. I wrote pages and pages of dense, elaborate adventures, requiring dozens of rooms and interconnected obstacle-item chains. Only a couple of them ever got made because computer time was so limited. One of my teachers said she’d try and procure me a copy of the game, because I loved it so much, but our only computer at home was an Amstrad electronic typewriter my Dad used for work, so I couldn’t have played it. I know that in a world where Twine and Ren'Py and RPG Maker exist Hazard/Rescue has moved beyond 'obsolete’ into 'perhaps this crude tool was once used by Cro-Magnon Man in his long migrations across the steppe’, but all the same, it was Hazard/Rescue that showed me how much I love making games. It was so simple, and it put so few barriers between you and what you wanted to build: no coding, no tutorials. You just imagined a game and typed it in, basically, and then your friends could play it. It was extraordinary.

They say that everything’s on the Internet somewhere. So far I have found that the one exception to this rule is Hazard/Rescue. But I keep looking, every year or so, just in case.

TREASURE MOUNTAIN!/TREASURE MATHSTORM! (PC, 1990)

uA: In the “Treasure” games of the Super Solvers series you went up a mountain to fox a guy called the Master of Mischief. There were other games in the Super Solvers brand, and I think they took place in schools and in cities and things, but I only cared about the mountain. The mountain is really the main character in the Treasure series, and the mountain was a symbol of unfettered hoarding.

Treasure Mountain! made you solve general-education questions – maths, spelling, verbal and non-verbal logic – in order to accumulate hidden treasures, which the Master of Mischief had stolen and dumped all over the mountain. At the summit you would drop all your treasures in a box and slide down to the bottom where you would get a single treasure for your trophy room. Then you’d start again. The more treasures you got, the higher your rank would tick up, which enticed you to find as many poorly-rendered treasures as possible. Treasure MathStorm! was exactly the same, only here the Master of Mischief had made it permanent winter on the mountain: it was always maths and never Christmas.

Your goal was to collect keys, money and nets. The keys were hidden in different mysterious groups of objects around the level. The money let you buy goods and services, and also, bewilderingly, could be expended to examine the groups of objects to find the keys. The nets would let you fuck up elves.

Caught elves would give you clues if you answered their questions correctly. Even if you got it wrong they’d give you a tiny amount of money. After reading my travails with Stickybear you might wonder how a youth such as myself could get through Treasure! without having to see the child psychologist, but the maths questions in Treasure Mountain! generally did not tax me.

Ten-year-old uA was confident that this one was possible.

Treasure MathStorm! was significantly harder (for me). Lots of the puzzles were fun, like working out weights and measures, but there was one puzzle called the “Time Igloo” that was my Siege of Rhodes. While we’re on embarrassing mathematical facts about yours truly, I still can’t read analog time, so when I was presented with this shit –

– I just fucked right off.

Thankfully you could do that. It was perfectly possible to scale the mountain with minimal treasures in either game. I think my favourite way of playing it as an urbanAnchorling was to stay on a single mountain level, earn fat stacks of cash, and buy a thousand nets to catch elves with. Not to answer their questions, mind, just for a psychosexual childish thrill.

It’s 30!!! I could go pro e-sports on this game now.

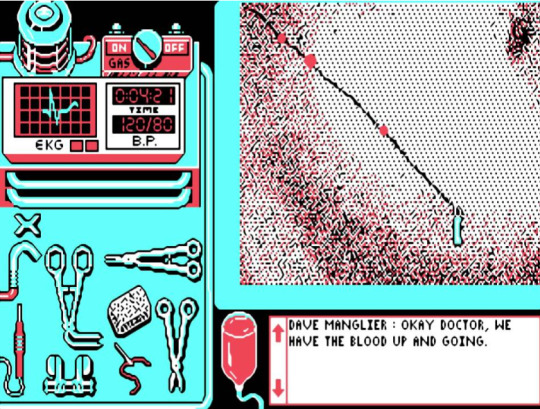

RUNNER-UP: LIFE AND DEATH (PC, 1988)

uA: You are an abdominal surgeon! Perform an appendectomy! See the words ‘subcutaneous fat’, then run away!!!!

I was doing my First Aid refresher training the other week and had to leave the room because the nurse mentioned the words “fingernail slippage”. I couldn’t come back for like five minutes. I’m on the hook to write a space horror trilogy about necromancers, just so you know.

RUNNER-UP: ???? (PRESUMABLY BBC/ACORN, ????)

pT: This was a puzzle game. It was brightly coloured, and had maths. All I remember - actually literally all I remember - is that it came in two parts, on two separate disks, and at the end of part 1 you fell into a river and were washed away. This was a huge cliffhanger. There was a little animation of you being swept down a bright blue river between hot green banks, your mouth an open black clump of pixels, and then it came up with 'Please Insert Disk 2’ or some equivalent dread mid-90s phrase of command. Problem was, our teacher had lost Disk 2. So I got to the end of Part 1, fell in the river, practically sprinted up to the teacher’s desk to find what happened next, and received the bad news.

But the teacher was sweetly optimistic that Disk 2 would turn up. So I couldn’t even grieve. I was forever caught between sorrow and hope, wondering each day if she would come up to me and say 'Guess what I found down the side of my desk!’

I am still waiting for Disk 2. I bet it’s going to be amazing.

RUNNER-UP: RAFT-AWAY RIVER (APPLE II, 1984)

uA: This was in the computer lab at school when I was in Standard Three. Pretty much every action you took made you wet or dying.

I played this just now on archive.org and died from being wet.

Now, when I were a lad, all of this was fields, you could still get a pint of beer for £1, and Fallen London was still called Echo Bazaar.

When you made an Echo Bazaar account, you hooked it up to your Twitter. Then, when you took actions in the game, you had the option of letting the game post a Tweet – a tiny snippet of narrative, summarising whatever it was you’d just achieved. This was called an ‘echo’. So if you had friends on Twitter who were playing the game, every so often you’d see something like:

This is an excitingly risky reproductive strategy (for the game, not the player), because it’s balancing intrigue against irritation. If people get sick of #ebz Tweets sprouting all over their timeline like mushrooms, it’s going to actively prejudice them against the game – so you have to hope that, before irritation sets in, they’ll have been sufficiently tantalised to click on a link and get ensnared.

I was using Twitter in 2011, and several of my friends were playing Echo Bazaar. I could very easily have developed a Pavlovian antipathy to the very words ‘London’, ‘bats’, and ‘delicious’. And, honestly, if you’d tried to elevator-pitch me on the whole concept, I’d have wrinkled my nose. ‘A dark and hilarious Gothic underworld’? Dear God, it sounds whimsical.I bet it’s got flippy-floppy skellingtons like a Tim Burton movie, and the kind of arch, pallid humour that used to characterise about 70% of fandom’s Rose Lalonde dialogue. I bet everyone wears hats.

But I was curious. I clicked a link. Three years later, I was using Echo Bazaar (now hight Fallen London) to plan my wedding.

Let me fill in a little context. FLis a role-playing game with only one real mechanic. You are a citizen of London some time in the very late 19th century. In this alternate history, the entire city of London has been uprooted and transplanted into a huge cavern below the earth, where it is ruled by mysterious cowled entities called Masters. Your character has four statistics: Dangerous, Persuasive, Watchful, and Shadowy. (Take a moment to admire how those are broad yet unambiguous – it’s very clear what you’re going to need for what – and how, just by existing, they sketch in the kinds of things the game will be about and hint at what you might be getting up to.)

Almost everything you do, from flattering a vicar to punching a wolf, tests your score in one of the four statistics. If you succeed, the vicar is charmed or the wolf is concussed, and you get a reward (which may be money, fame, or simply access to a more important vicar). If you fail, you take a penalty. Either way, your score in the relevant statistic gets slightly higher – so that if you fail often enough you will still get better, much as I did as an undergrad with Greek verse composition.

To prevent this from being a frustrating guessing-game, you’re given a sense before you attempt a challenge of how likely you are to succeed.

‘Straightforward’ there means I literally cannot fail, because these are Watchful tests and my character is extremelyWatchful. But it might also say ‘very modest’, or ‘almost impossible’, or something in between. (These days, you can also mouse over the words to get a percentage chance of success, if 29% means more to you than ‘high-risk’.) So you can tailor the challenges you attempt to just how lucky you’re feeling: do you want to stay safe and improve slowly, or roll the dice and hope for a big payoff? If you know it’s going to be almost impossible to thaw this particular vicar’s icy heart, you can be phlegmatic about failure, and unreasonably gleeful about success.

(Some people find this level of transparency unrealistic and ‘gamey’, but I actually find it closer to real life than many of the alternatives. In real life, if I try a task, I generally dohave some sense of how likely I am to succeed in it: I can almost certainly make this cake, whereas I probably can’t fix that laptop. In games, you don’t have that contextual intuition – you can’t compare the task at hand to other, similar things you’ve attempted in the past, or to your general sense of your own limits – so it really helps my immersion to have the game fill it in for me. Compare some RPGs, where you try to pick a lock and are told ‘Failure’ or ‘Skill too low’, and nothing else. So, what? Did I nearly have it? If I see a similar lock down the hall, is it worth my trying that one too? Or was I just stabbing blindly at the door, and the phone video my healer is now uploading to YouTube is about to reap thousands of upvotes on r/therewasanattempt?)

The only real ‘objective’ in FLis the story. In a sense, the whole game is one very long and complicated novel, where each individual page has been torn out and hidden in a different box. Information is tightly controlled and drip-fed at an exquisitely modulated pace. You learn very early in the game that London is the fifth city to have ‘fallen’; as you progress, you start to pick up more and more little hints to the identities of the previous four cities. By the time you’ve played for a while, and as long as you’ve been paying attention, you’ll know what the Fourth City was; you’ll know roughly where the Third City was, but may not be sure of its exact name; you’ll probably have a theory about the Second City; and you’ll be almost none the wiser about the First City. (I have still never seen a fully satisfactory proof of the First City’s identity.) But these Cities aren’t just hand-waved in as fodder for speculation. They’re concrete puzzles, with solutions you can piece together. I once spent more than a thousand words trying to figure out the meaning behind one particular location in the game (spoilers for Hunter’s Keep).

But obviously there has to be other stuff to keep you busy in your search for the next page of story. You can buy things for your character: I saved up for weeks to afford my Semiotic Monocle, and much of the fun for a late-game player comes in acquiring difficult, expensive, or limited-edition items to show off, just like in any MMO. There are also social actions. You can have a list of in-game friends, and you can invite these friends over to play chess, talk to them when the Nightmares are getting too much, even send them a card at Christmas.

In early 2014 urbanAnchorite and I were planning our actual, real-life wedding. This was a complicated process, made worse because she was still living in New Zealand, so the whole thing had to be sorted out by E-mail. We were keeping ourselves sane by sending our FLcharacters on adventures: I had two, Daniel and Evie, and she had two, Thomasina and Meredith. I’d been too busy with work to write anything substantial, so we kept up a running exchange of narrative snippets. Daniel and Thomasina were investigating forged antiquities while embroiled in an increasingly baroque flirtation. Then, for Valentine’s Day, Failbetter unveiled the option to marry another player in-game.

This was simple and realistic: the more you could spend, the more you could have. You needed to build up a quality called Organising a Wedding by spending other resources, and then eventually ‘buy’ one of a number of possible weddings, from a dubiously legal handfasting at the Docks to the society event of the season at St Fiacre’s Cathedral. So I have a string of E-mails from the time, full of paragraphs like:

I’ve E-mailed the Chaplain at John’s, making enquiries about using the chapel for a Nuptial Mass. I’ve also dragged Daniel and Thomasina’s Organising up over 100, largely by calling in an old favour and getting the Bishop of Southwark as the celebrant; he owes Daniel big time, and he’s one of my favourite NPCs in the game because he’s somewhere between Brian Blessed and Equius. My Connected: Church has gone down to 6, but never mind. I also used the ‘something old, something new’ option because I happened to have all the stuff lying around and I thought it was cute. There’s plenty more I can do: I have a Cellar of Wine and can get more, I have a decent cache of Blackmail Material, and I have a stack of Sworn Statements from being a Journalist for ages, though they exchange at 2 for 5 OW so they’re not as useful. I’m going to see if I can get my hands on some Fourth City Airag, but that’ll be pure luck.

In real life, we did not have much money and could not afford a big wedding. In the game, though, I was rich as Croesus. So we spent fictional currency like so much water, and got as big a wedding as we wanted. Daniel and Thomasina ended up married in St Dunstan’s, with the reception in the Shuttered Palace, and the occasion was attended by most of the game’s long-term NPCs, including at least two Masters and the Tiger-Keeper. It remains one of my proudest achievements in video gaming, and a validation of Dorothy L. Sayers’ famous advice:

At the time I was particularly hard up, and it gave me pleasure to spend [Lord Peter Wimsey’s] fortune for him. When I was dissatisfied with my single unfurnished room, I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered him an Aubusson carpet. When I had no money to pay my bus fare, I presented him with a Daimler double-six, upholstered in a style of sober magnificence, and when I felt dull I let him drive it. I can heartily recommend this inexpensive way of furnishing to all who are discontented with their incomes. It relieves the mind and does no harm to anybody.

In the last twelve months I’ve hardly logged onto FL. Moved by loyalty and affection I became an Exceptional Friend, which is what Failbetter call their subscriber programme, and which gave me access to a brand-new story every month; but these Exceptional Stories were of uneven quality, certainly compared to the rest of the game, and ironically they managed to cool my enthusiasm. One story in particular was very nakedly and unsubtly game-like in exactly the way FLis so good at avoiding – it was a repetitive grind culminating in an arbitrary Bioware-type choice between two factions – and, as stupid as it may sound, I felt like Daniel’s time was being wasted. It dragged me partway out of the illusion, and reminded me that I was playing a browser game in my coffee break, not exploring ghastly mysteries in a city forgotten by the light.

So I drifted away. I’d seen most of what I wanted to see. I’d chickened out of the game’s notorious unwinnable quest, Seeking Mr Eaten’s Name, because it destroys your character and I couldn’t bear to have Daniel destroyed now he was a married man with a nice house and an ocelot. But I’d accessed all areas; I’d tackled all the main story quests; I’d bought my Semiotic Monocle; I’d even finished the ‘secret quest’, Ambition: Enigma, which is hidden away for only nerds to find. There were still plenty of bits and pieces I hadn’t done, but none of them quite had their hooks in me.

I played and enjoyed Sunless Sea, Failbetter’s rather better-known nautical survive-em-up set in the FLuniverse, but was never able fully to resolve its balance of the traditional and the roguelike: in an early run I got lucky and pulled off so many impressive feats of exploration and derring-do, including getting the Scarred Sister to Naples, that I felt any subsequent run would be a disappointment. I backed its sequel, Sunless Skies, on Kickstarter (one of only two KS projects I’ve ever backed), and played an alpha build, but I think the transition to outer space may take me too far beyond my interests and too close to the horrifying maw of steampunk. I’ll reserve judgement until the finished product is released.

I’m actually more excited for Cultist Simulator(the other one), which is being made by Alexis Kennedy and Lottie Bevan, both Failbetter alumni, and releasing 31st May: although technically a much simpler game, it seems to preserve more of what I treasured about FLin the first place – crisp writing, sinister lore that has to be unpicked with tweezers, and an aesthetic of what I suppose you’d have to call occult melancholy.

(Alexis Kennedy, it should be said, has become one of my favourite writers on the Internet purely off the back of FL.He didn’t write the whole game himself by any means, and some of my individual favourite sections were the work of Yasmeen Khan or Nigel Evans, but he set the rules and the tone – and he excels at small-scale technical precision of the kind I really value. One good Kennedy sentence is worth your average short story, and it’s largely down to his facility for saying little and suggesting much that I first clicked on a Twitter echo back in 2011. Here, for example, is his 2,000 word dissection of how he wrote a single sentenceforCultist Simulator.)

But there’s something special about the game where you practised marrying your wife. uA has on her desk some small plastic models of our FLcharacters, which I bought for her off Hero Forge and painted ineptly with acrylic paint. We’ve put Daniel and friends in a Sims house and on an XCOM team. FLhas evolved beyond a browser game we both play, and into a shared cultural referent, a kind of background note in day-to-day life. I remember describing an event I attended as ‘an almost impossible Persuasive challenge’ in casual conversation with someone who’d never heard of the game. I have a whole tag on this very Tumblr for things that make me think of FL. I even adapted it into a set of tabletop rules so I could run it as a campaign for some friends. It’s just there, now, like a book you take off the shelf just to re-read the first page.

I know some new content has been added to the late-game since last I explored it, and one day soon I’ll probably go and check that out, for curiosity’s sake; but even if I never logged in again, Fallen London would be one of the most important games I’ve ever played. If you haven’t tried it, there’s a really extraordinary banquet of wonderful places and people and ideas there, just waiting for their next explorer.

Of all the games I’ve never finished – a long and humiliating list – I’m not sure there’s one I’ve startedquite so many times as Theme Hospital.

Theme Hospital is a game where you build and run a hospital. You win a level by amassing a sufficiently high score across several different categories: total funds, number of people cured, etc. Then you get a letter from the Ministry of Health encouraging you to move on to a new challenge, i.e. opening a brand new hospital in a new town (and thereby starting a new level). Most of the crucial scores can be accumulated by making a decent hospital and then keeping it functional for long enough. People cured, for example: you can’t uncure someone, so even if you’re only curing ten people a year, you will still inevitably end up meeting the requirement.

The sticker is a score called Reputation. Reputation can go down as well as up – if you cause a public health disaster, for example – and it can also just stay put: if you’re running a perfectly ordinary hospital that’s not collapsing but also isn’t distinguishing itself, your Reputation is going to hover in more or less the same place, no matter how long you play. In other words, you can’t drag up your Reputation just by treading water and being patient.

This is the first of many useful life lessons that Theme Hospital has taught me.

It was one of the first games I ever played purely by myself, on our huge beige late-90s PC back in Birmingham. I must have been about 11. I remember nothing about how I acquired the game: I’d guess my parents must have bought it for me, but it’s not the kind of game I’d naturally have expressed an interest in at that age, so maybe I saw it at a friend’s house or something. (Mum will know, if I ask her; the woman has the unfailing institutional memory of a particularly long-established Dwarven kingdom.)

At this point in my life I had very little experience with games, and, if it doesn’t sound too strange, I hadn’t really awoken to the idea that you could play games well. In a platformer, if you make a mistake, the penalty is obvious and immediate: rings go flying everywhere. But in a management sim, I just sort of assumed you did what you thought was right, and then hoped that the game arbitrarily judged you worthy of success. My developing brain had not yet got its teeth (brain teeth) into the concept of strategy.So I built my first hospital exactly the way it seemed natural to me to do, and won the level, because you can’t not win the first level of Theme Hospital. Once the levels actually started to require an understanding of the game’s mechanics and the ways they interact, I hit a wall.

Later attempts, periodically throughout my teens, were a bit more successful. I started to understand basic principles like ‘don’t make a room vastly bigger than it needs to be’ – yes, I’m sure in real life a GP would be delighted to have an office the size of your average ballroom, but in game terms a 4x4 cubicle with a window and a pot plant will have very much the same effect and won’t take up half of the hospital – and ‘put the toilets near where the patients are’. (I definitely remember an early game where I put the toilets in a completely separate wing of the hospital from all the medical stuff, because this seemed to me orderly and hygienic. If a patient was sitting waiting for General Diagnosis and needed the loo, they faced about a half-mile walk. Sometimes they would quite literally die on the journey. Later I thought: hmm, maybe it would save time if they didn’t have to go so far? This is your child’s brain learning.)

But – and this dates me more than anything else – it never occurred to me to go looking online for guides or tips. So a lot of things that make a real difference to the game in the later levels, such as focusing your consultants on early-stage diagnosis, passed me by. I just kept making hospitals I thought looked nice and worked well, and then every time I’d get to about level 7 or 8, where Reputation starts being a deal-breaker, and stall. My hospitals at this level would run, but they wouldn’t run wellenough.

I kept playing, though, because Theme Hospital was such an intensely satisfying game to play. I love laying out spaces. As a kid I used to fill exercise books with top-down plans of imaginary buildings. THgives you a big empty shell to fill, and just enough stuff that you can make pleasing personal decisions: where are you going to put the GP’s pot-plant? Next to his desk, so he can look at it? Next to the window, so it gets lots of light? Neither of these are mechanically relevant, since in the game doctors don’t look at things and plants don’t need light, but they feel important in your head. All the colours are bright and clean, and all the sounds are crisp. The benches you provide for patient seating are an acid green that almost glows, and you can rotate them with a fwip-fwip-fwipnoise before dropping them into place with this decisive clumpthat remains probably my favourite sound-effect in video games.

The humour is silly without being in-your-face wacky, and is shot through with a vein of gleeful darkness (you cure Slack Tongue Syndrome by… cutting off the patient’s enormous tongue with a big metal guillotine). The music: oh God, the music! There are games I’ve played in the last year and I can barely remember a note of the soundtrack, and yet I can and do still hum the entirety of ‘On the Mend’ while doing the housework. Even my parents loved the announcer, who punctuates gameplay with tannoy calls ranging from the metatextual (‘Look out for other Bullfrog products!’) to the bleak (‘Please try not to die in the corridors…’), all delivered in a cheery Lancashire accent. (Apparently her VA is, or was until recently, teaching Performing Arts at Blackpool and the Fylde College; I hope her students know they’re being taught by a legend.)

There are very few games for which I have such unalloyed respect and affection as Theme Hospital. I think about it a lot, particularly when scandals break in the news. You see, one of the things that damages your Reputation in the game, perhaps unsurprisingly, is patients dying in your hospital. But these people are ill; many of them have one foot in the grave by the time you diagnose them, let alone get them to treatment. So there is a very cruel and heartless thing you can do if you’re really struggling for Reputation: you can skim round your current patients, find anyone who’s at death’s door (represented by a little warning icon on their profile), and send them home.

The ‘send home’ button is meantto be used when you have a patient you literally can’t treat, because their condition requires facilities you don’t have yet. When you click it, it makes a sound like a whiplash, and the patient stalks out of your front doors with an angry red icon over their head. I have done this to critically ill patients, and then watched as they walked out the doors, got about twenty metres down my front drive, and dropped dead. And reader, all I felt was relief. Because if they’re not in the hospital building when they turn up their toes, it’s not my fault. Now I don’t have to soak up the Reputation damage that comes from letting a patient die.

That’s honestly not funny at all, when you think about it. And it did always make me feel bad, though not bad enough not to do it. But every time now I see a story in the news about some manager or administrator who did something obviously immoral, covered up some malpractice or faked some data, in an attempt to protect their own reputation or their employer’s, I think: yeah. Yeah, been there, actually. I certainly hope I wouldn’t have done that bad thing, but I kicked ill people out of my hospital so they wouldn’t die on my floor. I’m not confident of my own high ground here. Theme Hospital was where I learned that games can make you act like someone you’re not, or you hope you’re not, just by presenting you with tools you wouldn’t normally have. I remember in 2013 when Papers, Please came out, and everyone got terribly excited about its moral gradient: we had hot take after hot take about how the game’s genius was its message, the way it wore you down into a ruthlessly self-serving and compassionless way of living by subjecting you to exactly the same pressures that might be faced by someone who was in that position for real. Papers, Please makes us all complicit in atrocity! Sure, but Bullfrog pulled exactly the same trick in 1997, and I didn’t see the New Yorker paying any attention back then.

(POLITICALLY TENDENTIOUS SIDEBAR: I remember finding it really weird, as a kid, the way the hospitals worked. Patients came in, talked to their GP, got a diagnosis, and then you got a ‘ch-ching’ sound effect and a little banknote appeared above their head. They were paying for it! When Mum took me to the GP, we didn’t pay for it; everyone knew going to the doctor was free, just like going to the park. I mean, it was great for me, the hospital administrator, because if patients paid for diagnosis I could then make them pay againfor treatment, and if I was getting a bit short on cash I could just go and tweak the charge for diagnosis up a little bit – make every patient pay an extra $5 and hey presto, free money for me. If you don’t believe in free healthcare, or if you don’t think the NHS is a national asset that needs to be protected with walls of fucking steel, play some Theme Hospital for me and see what you make of it.)

It’s not a perfect game. All the doctors are male and all the nurses are female, which would no longer fly. The Epidemic system remains completely opaque to me: I’ve lost count of the times I have vaccinated every epidemic patient in my hospital, double-checked I’ve got them all, and then been told that I’m taking an enormous cash and reputation hit for failing to contain an epidemic. (I suppose that may have been intentional, but Christ, it’s infuriating.) The reliance on specialist clinics to cure single diseases gets repetitive in the late game, because you know you’re going to have to build at least one of every single clinic but you have to research them all from scratch anyway. My hospitals are always, alwaystoo cold. And there’s a problem shared by many sim-type games, where playing optimally forces you to abandon a lot of your imaginative investment. The pot-plant problem I mentioned earlier? The correct answer is ‘next to the door’, always, because then when a handyman comes to water it, he only has to step just inside the room. If you stick it under the window, the handyman has to walk all the way round the room to get to it, which is time he could be spending on fixing your X-Ray before it explodes. Pot-plants in rooms should really only ever be next to the door. At the extreme end, this is a picture I found online of a ‘decently optimal’ Training Room:

(It’s really efficient! The projector and the chairs are near the door, which minimises the amount of time doctors spend walking in and out; the skeleton is near the projector, because the doctor will sometimes walk to point at the skeleton and you don’t want that animation to take forever; and there are seven bookcases, all of which add value to the room but aren’t used for anything else, so can be shoved up the far end out of the way. The problem is that it looks absolutely nothing like a classroom. All four students are staring directly at the door, and none of them can see the projector screen, plus the bookcases look ridiculous clumped together like that. That doesn’t matter, because the game doesn’t keep track of things like sight-lines or ridiculousness, but I tell you for free, I would never build that room in any hospital of mine. I’m an artist, damn it. I have integrity. Boy, it’s so nice our classroom has all these windows, offering this unrivalled view of a bunch of arcade cabinets from behind!!)

I said at the start that I’ve never finished Theme Hospital. I probably never will, and I don’t particularly regret the fact. I keep coming back to itbecause it achieves what is, in a sense, the ultimate goal of a game: it’s good to play. Like a set of wooden blocks being nice colours and making a nice noise when you clonk them together, the process of mapping out a hospital and filling it with stuff looks nice, sounds nice, and feels nice. I don’t really need to see the final level (which, let’s face it, is going to involve building a big hospital and then getting a very high Reputation).

I’m certainly keeping an eye on Two Point Hospital, the spiritual sequel that’s in development with some of the original designers, and I may very well buy it, but I don’t need them to correct any errors or fill any gaps. All I really need to do is play the original’s first couple of levels every couple of years, when the moon is full and the need comes on me again to hear a bright green bench go clump, and I’ll have got what I wanted. That may not sound like high praise, but when I think about games I’ll still want to revisit when I’m 60, I can very easily see myself being tempted once more to fire up Theme Hospital for half an hour on my Applesoft Googlebook cybernetic replacement brain. There are many more technically impressive or artistically innovative games I’ve played for which I’m not sure I could say the same.

LikeSpelunky, I don’t know why I started playing Unreal Tournament. I must have been about fifteen, and I remember discussing it with some of my friends at secondary school, so maybe one of them convinced me to try it out. Again like Spelunky, it’s not a kind of game I’m normally drawn to. I’ve played a few first-person shooters in my time – it was kind of hard to be a young man in the 2000s and notend up playing first-person shooters, since GoldenEyeandHalowere both so fundamental to adolescent male social interaction – but it’s always a genre I’ve enjoyed with friends in the same room, rather than as a solo pursuit. (To this day, I think the closest I’ve ever come to playing and completing a solo FPS is with the Mass Effect games, which are party RPGs clad in a very thin FPS veneer.)

UT, though, I played all by myself, and not even against strangers on the Internet. I have never once entered a UTmatch against another human being. I played UTexclusively against robots.

This is not the point of deathmatch-type games. The bots are training dummies: they’re only there for you to practise your skills against. Oh, they run around and shoot and display human-like tactics – falling back if they’re injured, trying to sneak up on you from a blind angle – but they’re not meant to provide a full and satisfying experience any more than one of those machines that fires tennis balls out of a cannon is meant to give you a good tennis match. You’re supposed to learn how to play the game by fighting through a series of botmatches, and then head online in search of a real challenge. I simply decided I was having quite enough fun with part one, thankyou, and wasn’t really interested in part two.

Now, the bots in UTwere not ‘characters’ in any meaningful sense. This was before Overwatch, before even Team Fortress 2. They had names, and distinct (although similar) appearances, and that was pretty much it. But as I played against them over multiple matches, they started to take on personalities. Malakai was a coward; Dessloch was a thug. Alys was a worthy foe. I had a lot of respect for Alys. I tended to play team games, rather than free-for-alls, and I’d be pleased or annoyed if certain bots were assigned to my team: Christ, I have to tote Kosak around for this entire match? He sucks!

(As it turns out, this wasn’t completely due to overimagination on my part. UTis still admired today for having exceptionally good bot AI for the time, and I discovered much later that the bots weren’t actually interchangeable. There was one guy, Loque, who I particularly feared and hated for his tendency to disrupt my winning streaks: I’d have killed ten Blue Team bots in a row without taking a scratch, and then suddenly bam, headshot from nowhere and of course it would be Loque. I recently learned from this chart that Loque was the only bot in the game with an Accuracy stat of 100, so in fact the bastard genuinely was responsible for a disproportionate number of my deaths and I wasn’t just imagining it.)

Feeding into all this unnecessary and largely unsupported headcanon was the game’s own setting, in which players were contestants in a dystopian future’s wildly popular arena bloodsport. Each map came with a cute little description of how this particular rusting facility had been bought by Liandri Corporation and repurposed for the Tournament; an announcer with a deep movie-trailer voice would rumble out approving comments if a player was doing particularly well (‘MULTI KILL!’). Match scores were displayed on electronic leaderboards during the matches themselves, so if you were on your A-game you could glance up at a wall mid-firefight and see yourself at the top of the list. I’m not sure if the game ever tried to rationalise the fact that death was so temporary as to be laughable: you could literally be blown to pieces by high explosives and you’d reappear elsewhere in the arena five seconds later, unscathed. You could kill the same opponent twenty times in a five-minute match. Future science is a wonderful thing. But all these trappings gave a potentially grim and savage game – sixteen maniacs shooting each other in a disused laboratory – a preposterous, camp bombast, a kind of heavy-metal psychedelia of blood and flame and skulls set to a pumping rock soundtrack. I could only make sense of it by recasting the whole thing as a WWF set-up: steroid-swollen gladiators and gladiatrixes, strapped into a mixture of combat fatigues and bondage gear, swigging energy drinks in the dressing room and cracking stupid jokes before all barrelling out together into the glare of the spotlights and the roar of the crowd. Of course no-one was going to die.Look, I ‘killed’ Arachne sixteen times in last night’s match and now she’s over there giving me the middle finger. The death stuff’s just for the cameras.

I named my player avatar Wraith, after a minor character I was fond of in Wolverine canon, and because I couldn’t exactly step in there with a name like Matt. The chunky pistol you started each match with, the Enforcer, could be doubled up: if you found another one lying around, you could wield one in each hand, because it was that kind of game. I loved the dual Enforcers, and regarded them as my signature weapons, which is the kind of thing that feels absolutely tremendous when you’re fifteen. Online, this would only have got me murdered by better players with the sense to use better gear. Against the bots – whose skill shifted up or down to match the player’s own – it was viable and fun. My favourite arena was Morpheus, three skyscrapers jutting up impossibly high, miles above the Earth’s surface, with only vestigial gravity. You could take a run-up and jump clean off one rooftop, sail across the gap in glorious slow-motion – blazing away at opponents as you flew – and land on the other side as easily as if you’d hopped over a puddle. Laurence Fishburne himself could hardly have done it with such effortless style. Then, of course, you’d get capped with a sniper rifle round by Loque, but that just served to check o’erweening hubris.

There was something of the Iliadabout it, I suppose: these larger-than-life beefcakes locked in futile but heroic combat, ‘hands spattered with gore, straining to win imperishable glory’. If you kept killing without being killed – an aristeia, basically – the announcer, like the narrator, would make sure everyone knew about it. ‘KILLING SPREE’, he would proclaim, in a voice like thunder, and then as your kleosmounted he’d go up the ranks: ‘RAMPAGE’, ‘DOMINATING’, ‘UNSTOPPABLE!’, and finally, with perhaps just a trace of awe, ‘GODLIKE’. That was the peak of your glory; further than that let no man look. Once you were godlike, all you could hope was that the match would end before another in his turn took the life from you with the thrown spear or the arrow sped from the bow-string (or, more likely, the fucking GES Biorifle, which just covered you with toxic green gunge until you exploded).

I’ve never spent any serious time with a first-person shooter other than UT. Its sequel, UT2004, was too hefty a game to run well on my entry-level PC at the time. I dipped a cautious toe in the water of more ‘realistic’ shooters – a friend got me to try Counter-Strike– but next to UTit seemed beige and banal: I couldn’t instinctively grasp the difference between a BJ-600 assault rifle and a Banger Mk 5 light machine gun in the way I could when they were a plasma cannon and a rocket launcher, and I found it frustrating that getting shot killed you. (Obviously, getting shot in UTdoes kill you eventually, but you can soak up a surprising amount of punishment first.) Also, slinking in cover down a dusty desert street seemed pretty dull after being propelled in low-G through the guts of an enormous mechanical crypt while the voice of God roared UNSTOPPABLE! I experimented with TF2, which like UTis colourful and slightly ridiculous, but everyone else who played it online had evidently never done anything else in their entire lives, so I spent most of my first match dead. Overwatchstill tempts me – I’ve watched a couple of clips and felt something stir in my heart – but I suspect the same thing would happen, and I am not at a stage in my life where I want some bloke in Ohio screeching at me because I can’t use the Backflip ability properly or whatever.

What I want, honestly, is UTback. Every attempt I’ve made to get it running on my laptop has been a frustrating failure: it’s an old enough game that it requires all sorts of driver kludges to run on a modern system. I’ve downloaded this patch and undownloaded that patch and taken my graphics card out and dunked it in milk before reinserting it, and all I get is a stuttery, unplayable mess. I wish I could fix it. If, after a long day at work, I could just drop into DM-ArcaneTemple for five minutes and run around firing wildly into the air, I’d be happy. I don’t really care whether I hit anything.

I like to imagine the scene pre-match; the excitement in the commentators’ booth, the commotion in the stands. Have you heard? Supposedly Wraith is back! They brought him out of retirement for a special season! Wait, is he the guy who got like two hundred kills on Codex one time? I thought he was dead!Like, really dead! And there I’d be in the dressing room, strapping the Enforcer to my thigh, surrounded by the mingled glee and disbelief of the other old lags. Hey Wraith, sneers Dessloch, you got any better at dodging bullets since last time? I adjust my shades. I don’t know, boy. You got any better at firing ‘em?

The gate cranks up; the lights and the shouting flood back in. We all rush out to die, and the loser buys the beers.

There’s a bit in one issue of Sandmanwhere Lucien, the Librarian of Dream, is giving the reader a tour of his library – which contains every book ever written. He comments that he’s even got yourbooks. What’s that? You haven’t written any books? Yes you have, here’s one: The Bestselling Romantic Spy Thriller I used to think about on the bus that would sell a billion copies and mean I’d never have to work again.

I never actually had that book. Everyone has a novel in them, but I’ve never found mine. (My romantic spy thriller did very well and I’m proud of it, but here I am, still working.) What I did absolutely have, for years and years, was the bestselling video game that I used to think about on the bus that would sell etc. etc.

And oh, that game! What a masterpiece it was. A party-based RPG, with a strong narrative, characters you could care about, a flexible build system so you could be the kind of PC you enjoy being, big dramatic set-piece battles, and – crucially – grid combat. No dull JRPG auto-fights where you hammer the boss with your strongest spells for eighty turns until he finally switches to his second form and becomes immune to poison; no irritating real-time-with-pause compromises where you queue up a bunch of brilliant manoeuvres, hit space, and watch your party completely fail to execute any of them. Real, proper, granular, transparent, beautiful grid combat. Tank holds the bottleneck while the mage charges something cataclysmic in cover and the rogue patiently circles to the higher ground, and you know when you’re in range because there’s a bunch of fucking squares on the floor that tell you so. Exquisite.Oh, this is my stop.

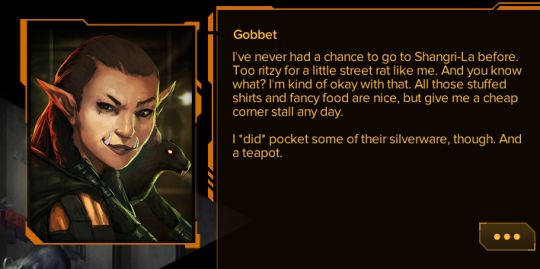

Then it turned out someone had actually made that game, and it was called Shadowrun Returns.

Okay: to be really specific, it was actually called Shadowrun: Dragonfall andShadowrun: Hong Kong. The first game, plain ol’ Shadowrun Returns, is a dress rehearsal. A lot of the crucial bits are in place, but it lacks the scope and polish of the other two; it’s shorter, the plot is less interesting, there are no side-quests to speak of, and it’s missing a few specific features I really value (such as levelling up your party members). But the key point here is that every RPG I have played since these three games has left me saying ‘It was pretty good, but I wish it had been more like Shadowrun Returns’.

I got very lucky! I had no association at all with the Shadowrun setting before this; indeed, having never been a tabletop gamer in my youth, I was only very dimly conscious of its existence. Nor is it all that obviously my jam. I’m fond of cyberpunk, sure, but I hate elves and all those who elf in them, so getting your elves in my cyberpunk is not a peanut butter/chocolate situation so much as a broken glass/mashed potatoes one. (Show me an elf who isn’t really annoying! Trick question. You can’t.)

So, from a content perspective, Shadowrun Returns and I were by no means fated to meet. But with mechanics like this, you could have set the entire trilogy in the world of Barbie Horse Adventures and I’d still have played it. Here are just a few of the things it does right:

- Character building. To start with, the game lets you build your own character, so you’re not stuck playing some shounen schmoe with a penchant for friendship speeches. Then, as you progress, you’re topped up with regular helpings of stat points. I believe very strongly that stat-point systems should work towards interesting and personalised character design, rather than against it. I’ve played too many systems where, for example, if you’re playing a physical fighter, there is only ever any point in increasing your Strength; putting points in Intelligence or Proficiency (Gardening) is not only futile, since you’ll never get to use those statistics, but actively hampers your character, as now they’ll never be as strong as a ‘pure’ example of their class. In SRyou get enough points that you can afford to focus on one core stat while still bumping up a couple of others on the side, so that my lightning-fast gunslinger, for example, ended up with insane Dexterity but also quite good Charisma. She wasn’t quiteas good at talking to people as she was at shooting them, but it remained a viable backup plan.

(Increasing Charisma lets you give your character ‘etiquettes’, which are somewhere between areas of expertise and habits of speech, and which unlock new dialogue possibilities: if you have the Security etiquette and you’re talking to a guard, you can commiserate with her about the tedium of the job and swap a couple of war stories, so she’ll accidentally drop a hint about the location of the main server room. But you can pick up a first etiquette extremely cheap – so even if your orc street samurai is literally just a killing machine, with no proficiency in anything but swords and the swinging thereof, you can easily fill in a smidgen of backstory and apply a thin coat of texture by picking her etiquette. In which case you should, obviously, pick Academic. ‘Time to die, punk – although I appreciate that killing you with a sword, a fundamentally closuralmode of discourse which seeks to limit and confine the available hermeneutics, itself ironically introduces apertures (in this case, wounds) into the literal ‘corpus’ of your body.’)

- Progression.As you go through the game you acquire party members, equip better weapons and armour, and accumulate cash – all those juicy, soothing RPG identifiers. But they’re all kept under tight control. You never get very manyparty members – four in Dragonfall, five in Hong Kong – so you can afford to spend time getting to know all of them without it feeling like a list of chores. New gear is drip-fed rather than sluiced in by bucket; if you use assault rifles, there are only half-a-dozen available in the whole game, so you never spend time scrolling down five pages of options, stewing over whether +5% armour penetration but -2% accuracy is a better deal than +10% burn chance but -3% libido. And you never end up drowning in money, so purchases matter; you won’t reach a point where you can just buy whatever you like (nor does the game have to include cash-sponge ultimate weapons costing the same as a small country, which I always think is a cheap way of avoiding late-game financial boredom). If you get back from a run, and find you’ve saved up enough money to buy that intensely desirable new armour you’ve been ogling for the last three missions, it feels great. You walk away from the shop feeling like a badass in cool new armour that you, a hard-working shadowrunner, earned with the sweat of your brow, not like you finally got the numerical value of $playerwealth to go higher than the numerical value of $armourcost.

(The characters, incidentally, are all great. Gobbet, the garbage baby orc shaman with her two pet rats, who when not summoning horrible arcane constructs basically lives in a dumpster and eats discarded kebabs, is one of my favourite RPG party members of all time. She’ll follow you into Hell, and then raid the Devil’s trash for chips.)

- Combat.Yes, it’s grid-based, and yes, that for me is the holy of holies. I regard it as axiomatic that any game in which you control multiple characters during combat either already is grid-based, or would be improved by being grid-based. But my favourite thing in SRis that combat always takes place on the same screen as exploration. If you’re poking around a disused warehouse and you get jumped, you don’t switch to a separate ‘battle screen’; the combat UI simply appears overthe terrain you’re already on. This is great, because it means when you’re exploring a potentially dangerous area, the back of your mind starts working on what to do if shit kicks off. (That pillar’s going to make great cover if guards suddenly bust through the hatch over there…)

Battles can be optional, but are never random: there’s no identikit pockets of appropriately-levelled foes just kind of loitering on the way to your next objective because God forbid you should have to go too long without a fight. When you do draw your weapon, there’s a simple and non-fiddly cover system that strikes a good balance between plausibility and cool. Yes, your team-mates should always end the turn in as much cover as they can, but you can dash from place to place to get a better angle – gunfights are fluid and cinematic, rather than getting bogged down with everyone hiding behind crates and fruitlessly trading shots. Even melee attacks remain plausible, which is always hard to pull off in any setting with guns. Overall, getting into a fight feels scary and awesome, just the way it ought to (in a video game). When the evil CEO slaps the alarm button and five goons in body-armour come barrelling in through the doors behind him, you get a real sense of: okay, it’s on.Not just ‘oh Christ, more of these guys’.

Also, everything is gorgeous. Check it out:

Now That’s What I Call Cyberpunk. Look at all that detail! Every environment in the game is stuffed full of really deft little touches, and areas never feel repetitive – basic elements are slotted together and then garnished with unique chunks of set-dressing, so that although you’ll come to recognise motifs and architectural styles, you’re unlikely to feel that this street is just a clone of the previous street but with the dustbins in a different place. SRdoesn’t lean too hard on the idea of cyberpunk being nothing but cold metal and grime, which I like; this is Cafe Cezve, a location from Dragonfallwhere you can sometimes pick up quests –

It’s a cafe. It has a piano, and plants, and stuff. It’s not just a big blue neon box where you jack into the Baristanet with your ‘trodes and download yourself a grande caffstim or stimcaff or whatever the fuck. Cyberpunk being about alienation and the subjugation of human identity by the remorseless grind of technocapitalism doesn’t actually mean the whole thing has to take place in a series of trash-strewn alleyways and no-one is ever allowed to laugh.

I think the thing I admire most about the SRtrilogy is its efficiency. I’m (finally) playing through Dragon Age: Inquisition at the moment, and seeing for myself what a vast, overstuffed, exhausting, five-course-Christmas-dinner slogof a game it is. You can’t move without being deluged in options, because options mean freedom and freedom is good. Lots of party members, all of them mechanically and aesthetically customisable to your heart’s content! Heaps of largely interchangeable loot, or if you prefer you can make your own! Change every aspect of your castle’s decor! Wander in circles looking for bandits until you’ve completely forgotten what the story is or what you were meant to be doing! Conversely, SRgives you options, but never very many of them. Each mission is an individually wrapped chocolate: you go to the place, do the job, and then you leave and you never go back there again. You can take side missions, but there’s only ever a couple to pick from; you can level up your party members, but whenever you do, it’s a matter of choosing which of two skills you want them to have, and the other one is lost for good. There’s just enough choice for you to feel like you’re playing the game your way, and no more. The result in each case is a game which leaves you hungry for seconds, rather than bloated and slightly queasy.

Unfortunately for me, Harebrained Studios have declared themselves done with the series; having made an RPG that more or less attained my ideal of Platonic perfection, they’ve casually decided that was fun but they’d like to try something else. Obviously I respect and indeed applaud their artistic autonomy and their desire not to stagnate, but also, God damn it. I just want more; more tense, atmospheric little stories for my shadowrunner (on whom I dote to the extent that I made her a mixtape) to sneak and hack and lie and shoot her way through. I feel like my favourite TV show got cancelled. But Rick and Ilsa will always have Paris, and I’ll always have Seattle, Berlin, and Hong Kong. There’s an official Shadowrun Returns level editor, which can theoretically be used to construct entire original campaigns; maybe one day, when I have a lot of time on my hands, I’ll settle down with it and I’ll make that bestselling romantic spy thriller, for nobody else but me. Shadowrun: Oxford. Now that would be a game.

[All three Shadowrun Returns games are available on GOGorSteam for between £10 and £15 a pop, and are often substantially discounted in sales. If you’ve read this and already know you want in, it’s absolutely worth starting with the first game: it has more rough edges than the other two, but it’s still a damn fine piece of work. If you’re just curious, I’d recommend trying Dragonfall, the second in the trilogy, which requires no knowledge at all of the previous game but improves on it in several respects.]

I started playing Spelunky– the ‘enhanced edition’, not the lo-fi original – in March 2014, during the last Oxford vacation I ever spent at my childhood home in Birmingham. I don’t know why I bought it. It was cheap in a sale on GOG, but even so, it’s a famously hard platformer and I am famously bad at platformers. I never honed those nerves and thews on Mario. I miss jumps; I get stressed. I think I lasted half a level in Meat Boy. I ought to have bounced off Spelunkyafter my first handful of deaths.

Instead, I got hooked. I’d play it a few times (which doesn’t take very long; early in one’s Spelunkycareer surviving for five minutes is a significant achievement) and then decide it was too hard and not for me. The next day I’d fire it up again, wondering if I’d somehow magically got better at it overnight. This lasted for the rest of the vacation, until I went back to work and lost all my free time again.

That summer, Taz moved to the UK. We spent the first month literally living in my office, cooking dinner on a portable camping stove and using college showers, because we didn’t have anywhere else. Our days were taken up with trying to find a flat we could rent, along with wedding planning, setting up bank accounts, and all the other jobs that breed from the dead land when someone moves country. I showed her Spelunkyas a curio – this is the game I was complaining to you about back in March! – and promptly fell back into the same pattern: die, throw up hands in exasperation, quit, sneakily restart half an hour later because thistime I’ll know not to…

ReplayingSpelunkynever palls, because its levels are randomly-generated. They follow the same narrative arc every time – there are always four Mine levels, then four Jungle levels, and so on in predictable strata down to the boss – but each level is spawned afresh from a procedural generation system so clever it still feels to me like magic. I have never, in thousands of games, seen a level spawn in such a way as to be impossible. (This may well be quite simple to achieve if you understand computers, but let me keep my peasant’s awe.) If you played Level 1 a hundred times in an old-school platformer, you would eventually come to know it so well that it would be boring; you’d be able to play it by muscle memory, without really paying attention. If you play Level 1-1 in Spelunkya hundred times, that’s a hundred completely new challenges, but – crucially – all requiring the same set of mechanical skills. If you’ve mastered the reflex of catching the edge of a platform so you don’t fall far enough to take damage, you can use it to make your life easier and expand your available options in basically every single level from then on. It’s almost like learning a language: if you know the forms of a certain verb, you can recognise it wherever it turns up, not just in the one specific piece of text where you originally encountered it.

Taz and I started rewarding ourselves for completing difficult or annoying jobs with a quick burst of Spelunky.At first we’d take turns: I’d die, then she’d die. Later we hit on an accidental masterstroke, and started playing alternate levelsrather than alternate games. I’d play 1-1, then hand over to her for 1-2 (easy to manage, because when you finish one level the game doesn’t move on to the next until you tell it to – a tiny but important design choice). Playing like this fundamentally alters the experience. Normally, if you’re taking turns with a game you both enjoy, some part of you always wants the other player to hurry up and die so you can have another go. But in Spelunky, at least once you get past your earliest failures, the important thing is as much howyou finish the level as whether you finish it at all. Do you reach the exit on full health, with a well-stocked reserve of bombs, the spike boots, and the pickaxe? Or do you reach it with a single heart remaining, having idiotically lost the shotgun because you got stunned by a bat and dropped it into a spike pit? So you become tremendously invested in the other player’s success, because the better they do, the easier time you’re going to have on the next level – and you become intensely careful of your ownsuccess, because if you lose health or items pointlessly, you’re taking them away from your partner. “Sorry,” I’d moan, handing over to Taz after a spectacular last-second fuckup cost me (and therefore her) two hearts and our last rope. “It’s cool!” she would always tell me, kindly.

Welp, can’t see anything bad in this bit of ooohhhh my GOD

This gradually developed into a kind of mutual artistic appreciation. We would watch each other in near-total silence, no backseat driving, occasionally murmuring “Nice” or “Not your fault” in response to dramatic moments. The level would end and we’d both relax, and hand over the laptop with a brief post-mortem: “I’m really sorry, that crate was a waste of time. I should have just left it.” “Nah, it was a good call. Could have been bombs.” Or just the purely aesthetic: “That jump was gorgeous,” I remember her telling me once, with the meaningful admiration of the expert who knows how difficult what you just did actually was. We learnt each other’s habits, too. Taz is always a little more flamboyant than me, a little more prone to leaps of faith. On a good day she’ll effortlessly swing moves I’d never have dared attempt, but one mistake shakes her confidence and she starts making more. I’m clinical and neat to a fault, but I waste time vacillating: I can get that crate – no, it’s too hard – no, I canget it – but then I’ve lost five seconds, and at the ninety-second mark the ghost appears and things get a lot harder. Taz is an artist with the climbing gloves, which I irrationally loathe, but gets timid with the shotgun because she doesn’t calculate the recoil. I depend near-fetishistically on the spike boots, and will mutter doom-laden prophecies if we haven’t found some by the end of 2-4. She hates the Black Market; I hate the Worm.

(Spelunkyhas no on-screen timer. We both know, almost to the second, when ninety seconds is nearly up, based on nothing but habituation and the background music.)

Four years later, we no longer play Spelunkynearly as much as we used to. Sometimes months will pass and we never touch it at all. But we’ve played enough now that the skills are written deep, so when we return to it, we’re a little rusty but we bounce back fast. And we always do come back to it, in the end. I wouldn’t honestly call either of us good at it, even after all that practice: we’ve reached Hell, the secret area, maybe a dozen times, but we’ve still never beaten the secret boss. We don’t use any of the strategies that mark out serious players, like ghostrunning or deliberately looting the Market. We read about the Solo Eggplant Run, a feat so perversely difficult to achieve that the designers didn’t realise it was possible, with the wide-eyed excitement of two kids on the primary school football team watching the World Cup final. But we’re just good enough to feelgood – to ride the high of a patiently learnt skill being pushed to its limit, the sugar rush of competence as we drop under a psychic blast and skip straight over a crush trap while sticking two bombs squarely to Anubis’ horrid snout.

It’s probably not the last time I’ll say this, but I’m not sure why I love this game so much. I don’t generally gravitate towards games that depend on reflexes and speed – I like my combat turn-based and my timers non-existent – or towards games whose adherents say ‘yeah, you have to get good to really understand how good it is’. (Not that I regard the latter as an unworthy or undesirable quality in a game! I just have very little confidence in my own ability and am easily scared off.) Aesthetics are certainly important. I’ve never mustered the courage to play Dark Souls, because it looks so big and Gothic and intimidating that it seems to growl HARDCORE PLAYERS ONLY, and I found Binding of Isaac too cruel and scatological to enjoy, with its nostalgie de la boue for flies and worms and blood and shit (all rendered in a faux-adorable style). Spelunkylooks like I think adventures should look: deep and rich, with sinister idols and jewels and flaming torches. But there’s also just something about its remorseless clarity; its careful fairness (all rules are consistent, and if something hurts you it will generally hurt enemies too); its absolute mechanical predictability. I love transparent games – the kind that set everything out right there in front of you, look you dead in the eye, and wink. Spelunkycan surprise you, but it shouldn’t. After you’ve played a few games you ought to be able to see everything coming. You won’t, of course, but that means when you die you don’t say: what? Why did THAT happen? You say: oh God, I forgot about the arrow trap, didn’t I? It was right there and I forgot about it. Next time I will definitely not forget about arrow traps.

And then you push the button, and start again.

[Spelunkyis available from GOG for £11.39, Steam for £10.99, and probably from various other places too. It’s also on XBLA and PSN. You can play the original lo-fi version for free; I’ve never tried it, so I’m not sure how exactly they compare, but the gameplay seems to be very much the same.]