#agriscience

The conference ‘Feeding the future: can we protect crops sustainably?’ was a tremendous success from the point of view of the technical content. The outcomes have been summarised in a series of articles here. How did such an event come about and what can we learn about putting on an event like this in a world of Covid?

This event was born from two parents. The first was a vision and the second was collaboration.

The vision began in the SCI AgrIsciences committee. We had organised a series of events in the previous few years, all linking to the general theme of challenges to overcome in food sustainability. Our events had dealt with the use of data, the challenge of climate changeandthe future of livestock production. Our intention was to build on this legacy using the International Year of Plant Health as inspiration and provide a comprehensive event, at the SCI headquarters in London, covering every element of crop protection and what it will look like in the future. We wanted to make a networking hub, a place to share ideas and make connections, where new lines of research and development would be sparked into life. Well, then came Covid…

2020 is the International Year of Plant Health.

From the start, we knew in the Agrisciences group that this was going to be too much for us alone. Our first collaboration was within the SCI, the Horticulture Group and the Food Group. Outside of the SCI, we wanted collaborators who are research-active, with wide capabilities and people who really care about the future of crop protection. Having discussed a few options, we approached the Institute of Agriculture and Food Research and Innovation, IAFRI and later Crop Health and Protection, CHAP.

By February 2020, we had our full team of organisers and about half of our agenda all arranged. By March we didn’t know what to do, delay or virtualise? The debate went back and forth for several weeks as we all got to grips with the true meaning of lockdown. When we chose to virtualise, suddenly we had to relearn all we knew about organising events. Both CHAP and SCI started running other events and building up their experience. With this experience came sound advice on what makes a good event: Don’t let it drag; Keep everything snappy; Make sure that your speakers are the very best; Firm and direct chairing. We created a whole new agenda, based around these ideas.

How do you replicate those chance meetings facilitated by face-to-face events?

That still left one problem: how do you reproduce those extra bits that you get in a real conference? Those times in the coffee queue when you happen across your future collaborator? Maybe your future business partner is looking at the same poster as you are? It is a bit like luck, but facilitated.

We resolved this conundrum with four informal parallel sessions. So we still had student posters but in the form of micro-presentations. We engineered discussions between students and senior members of our industry. We tried to recreate a commercial exhibition where you watched as top companies showed off their latest inventions. For those who would love to go on a field trip, we offered virtual guided tours of some of the research facilities operated by CHAP.

Can virtual conferences take the place of real ones? They are clearly not the same, as nothing beats looking directly into someone’s eyes. But on the plus side, they are cheaper to put on and present a lower barrier for delegates to get involved. I am looking forward to a post-Covid world when we can all meet again, but in the meantime we can put on engaging and exciting events that deliver a lot of learning and opportunity in a virtual space.

Feeding the Future was organised by:

James Garratt, SCI AgrIsciences

John Points, SCI Food

Liliya Serazetdinoza, SCI AgrIsciences

Robin Blake, SCI AgrIsciences

Bruce Knight, SCI AgrIsciences

Sebastian Eves-van den Acker, SCI Horticulture

Neil Boonham, IAFRI Newcastle University

Katherine Wotherspoon, IAFRI FERA

Darren Hassall, CHAP

Technical and administrative support was provided by:

JacquI Maguire SCI

Shadé Bull SCI

Theo Echarte SCI

Sandy Sevenne CHAP

Claire Boston-Smithson, IAFRI FERA

Guest chairs and moderators were:

Rob Edwards Newcastle University

Ruth Bastow CHAP

Richard Glass CHAP

Recently, our Agri-Food Early Career Committee ran the third #agrifoodbecause Twitter competition. Today we are looking back over the best photos of the 2020 competition, including our winner and runner-up. Entrants were asked to take photos and explain why they loved their work, using the hashtag #agrifoodbecause on Twitter.

Our 2020 winner, Jordan Cuff, Cardiff University, won first prize for his fantastic shot of a ladybird. He received a free SCI student membership and an Amazon voucher.

#agrifoodbecause insect pests ravage agriculture through disease and damage. Naturally-occurring predators offer sustainable biocontrol, but their dynamics must be better understood for optimal crop protection. @SCIupdate@SCI_AgriFood#conservationbiocontrol️️pic.twitter.com/ss4WjdB8ky

For the first-time ever we also awarded a runner-up prize to Lauren Hibbert, University of Southampton, for her beautiful root photography. She also received a free SCI student membership and Amazon voucher.

#agrifoodbecause developing more environmentally friendly crops will help ensure the sustainability of future farming.

Photo illustrating the dawn of root phenotyping… or some very hairy (phosphate hungry) watercress roots! @SCI_AgriFoodpic.twitter.com/29u533Xyow

There were also many other fantastic entries!

#AgrifoodBecause My research looks at the potential biocontrol of parasitic wasps on #CSFB, major pest of #OSR! Combining field and lab work to work towards #IPM strategies pic.twitter.com/YqJnBM4CVf

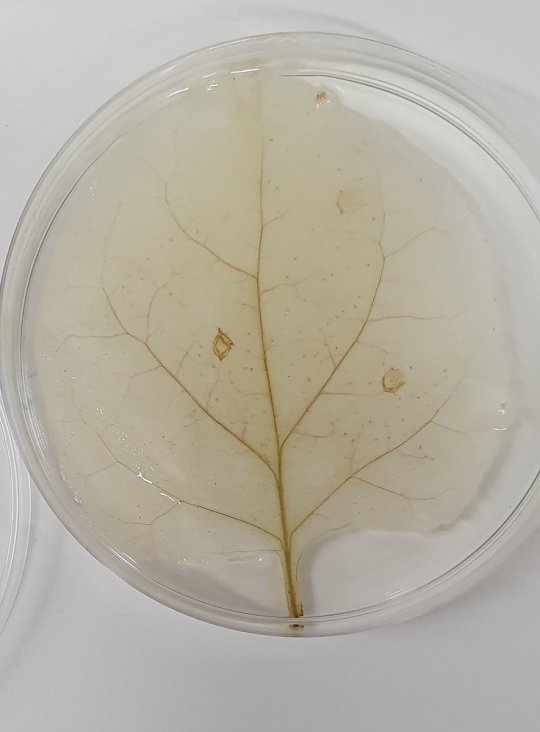

#AgrifoodBecause we need to work out which tools fungi use to damage our crops. Sometimes crops are tricky to work with so models have to do pic.twitter.com/mrdk2tRgC6

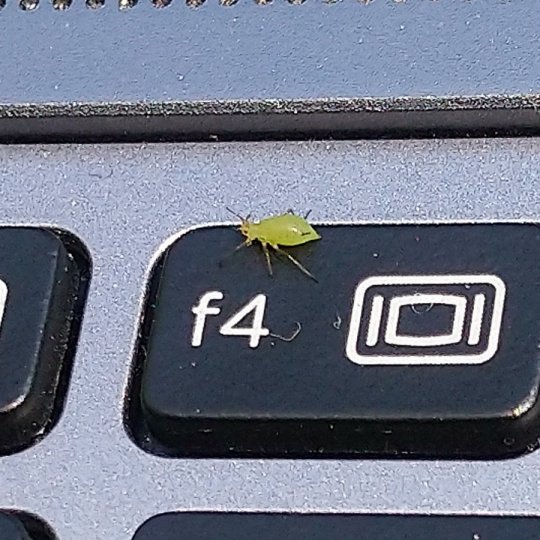

#agrifoodbecause we need to protect the crops to feed the world while repairing and protecting a highly damaged ecosystem. There is no delete option! #foodsecurity#noplanetb#organic#earth#wildlife#insectpests#beneficialinsectspic.twitter.com/JXfycRc0tx

Once again, it was an incredibly successful online event, with fascinating topics covered.

To find out more about the Twitter competition, follow our SCI Agri-Food Early Careers Committee Twitter @SCI_AgriFood and look out for #agrifoodbecause.

This year’s wheat harvest is currently underway across the country after a difficult growing season, with harvest itself being delayed due to intermittent stormy weather. The high levels of rainfall at the start of the growing season meant that less winter wheat could be planted and dry weather in April and May caused difficulties for spring wheat as well. This decline in the wheat growing area has caused many news outlets to proclaim the worst wheat harvest in 40 years and potential bread price rises.

Difficult weather during this year’s growing season. Photo: Joe Oddy

This is also the first wheat harvest in which I have a more personal stake, namely the first field trial of my PhD project; looking at how asparagine levels are controlled in wheat. It seemed like a bad omen that my first field trial should coincide with such a poor year for wheat farming, but it is also an opportunity to look at how environmental stress is likely to influence the nutritional quality of wheat, particularly in relation to asparagine.

The levels of asparagine, a nitrogen-rich amino acid, in wheat grain have become an important quality parameter in recent years because it is the major determinant and precursor of acrylamide, a processing contaminant that forms during certain cooking processes. The carcinogenic risk associated with dietary acrylamide intake has sparked attempts to reduce consumption as much as possible, and reducing asparagine levels in wheat is a promising way of achieving part of this goal.

Asparagus, from which asparagine was first discovered and named.

Previous work on this issue has shown that some types of plant stress, such as sulphur deficiency, disease, and drought, increase asparagine levels in wheat, so managing these stresses with sufficient nutrient supply, disease control, and irrigation can help to prevent unwanted asparagine accumulation. Stress can be difficult to prevent even with such crop management strategies though, especially with environmental variables as uncontrollable as the weather, so it is tempting to speculate that the difficulties experienced this growing season will be reflected in higher asparagine levels; but we will have to wait and see.

Joe Oddy is a PhD student at Rothamsted Research and a member of SCI’s Agri-Food Early Careers Committee.