#anaesthesia

Anaesthetic.

Small warm-up sketch after a really really long time of no painting. I have finally graduated uni ♥ so I can hopefully relax for a tiny bit, as a 3D student, lockdown did not really help my final submissions, but I somehow got there…

——————————————

https://www.youtube.com/c/weroni

https://www.etsy.com/shop/weroniart

Post link

“Poems, regardless of any outcome, cross the battlefields, tending the wounded, listening to the wild monologues of the triumphant or the fearful. They bring a kind of peace. Not by anaesthesia or easy reassurance, but by recognition and the promise that what has been experienced cannot disappear as if it had never been. Yet the promise is not of a monument. (Who, still on a battlefield, wants monuments?) The promise is that language has acknowledged, has given shelter, to the experience which demanded, which cried out.”

- John Berger, And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos

Art: Miki Kratsman, Untitled, 2001. 116 x 170 cm, digital inkjet print.

Post link

Beating Heart Cadavers

Last year we had a terminal (non-recovery) fish practical which required fresh cadavers. The fish were humanely euthanised with an anaesthetic overdose. As an added precaution, the gill arches were then cut (causing them to bleed out and preventing respiration) and the spinal cord transected (obstructing electrical signals from the brain). Despite these measures, the fish hearts continued to beat for several minutes. Even once removed from the rest of the body, they continued to beat. As you can imagine, it was quite disconcerting, but we were all reassured that the fish were, in fact, dead and unable to feel any pain.

I hadn’t given it another thought until I came across this video yesterday and my curiosity got the better of me. So I did what any ex-vet student would do - RESEARCH!

The heart continues to beat because, unlike most muscles in the body, the heart doesn’t rely on electrical impulses from the brain, but instead generates its own electrical impulses from specialised cells within the heart. These cells can continue to fire as long as they have sufficient ATP (energy). Apparently this phenomenon can (and does) occur in humans too.

So then I started thinking about the process of dying, how “death” is defined, and what criteria are used to determine death. Is a patient dead when the heart stops beating, or when respiration ceases? Are they dead when there is no longer conscious thought, no response to stimulus, or an absence of electrical activity in the brain (“brain dead”)? Or a combination? It’s clearly a controversial question because death isn’t a single event, it’s a process! Cells, tissues and organs die at different rates.

While I was reading, I came across the term “beating heart cadaver” which I hadn’t heard of before. A beating heart cadaver is a body that is pronounced dead (by the brain dead definition), yet retains functioning organs and a pulse. Because the brain stem is dead and can’t control ventilation, the body is connected to a medical ventilator which keeps the blood oxygenated. This blood is circulated around the body by the heart, which continues to beat independently. Beating heart cadavers are known to “survive” for up to 20 years! These cadavers are even capable of maintaining pregnancies! Fascinating right?

In the vet industry we routinely determine whether an animal is alive or not simply by feeling for a pulse and using a stethoscope to auscultate the heart. I suppose if the heart ISN’T beating, the animal is definitely dead. And with pharmacological euthanasia, the cardiovascular system is likely to be the last to go (after nervous and respiratory systems). Even so, assessing cardiovascular function now seems an over-simplified means for determining death in veterinary patients. I will certainly be giving more thought to my death criteria from now on.

If you’re as fascinated by this topic as I apparently am, I found this interesting BBC article which is worth a read: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20161103-the-macabre-fate-of-beating-heart-corpses

Check out the videos of my fish practical here: https://www.instagram.com/p/BtaeSQKnW-a/

Post link

Anaesthesia Rotation

(1001 Ways To Kill Your Patient)

While most people in my group were terrified to begin two weeks of anaesthesia, having spent six years working in a vet clinic on weekends and often playing anaesthetist, I felt quietly confident about this rotation. I was already competent drawing up and administering medications that a vet had advised, recognising when a patient’s vitals were abnormal and following instructions to correct this. I was hoping this rotation would provide me with an explanation behind these actions so I would be able to problem solve and make decisions independently.

In the introductory session, we were led to believe that we would be the primary anaesthetists, and a supervising vet would be around and ready to jump in if things went pear shaped. It quickly became evident, however, that the vets and nurses didn’t have the tolerance or patience for teaching. They simply couldn’t resist interfering. A perfect example of this was placing catheters. You’d think that getting the catheter into the vein would be the hardest part, right? Wrong. It’s all in the taping my friends. You would also think, perhaps, that as long as the tape secures the catheter and ensures it remains in the vein for the duration of the procedure, it was serving its purpose. Also wrong. In the university hospital, there are about 10 types of tape that all need to be applied in a certain order and in a very specific way. The catch: every single department and staff member does this slightly differently. The student’s job is to ascertain the ‘correct’ technique for the specific supervisor and carry it out without the slightest hesitation. Knowing this to be the bane of many a student’s existence, after placing my first catheter of the rotation, I asked the supervising vet if they had a preference for taping. She replied, to my astonishment, “No! As long as the catheter stays in, you can tape any way you like!”. I proceeded to secure the first piece of tape, when suddenly - “NO! Not like that! I like to do it this way because…”. And just like that, I was robbed of my taping responsibilities and forced to endure yet another 10 minute lecture on how to best tape in a catheter. It was micromanaging in the most extreme sense. A few days on, my friend joked that if she heard one more person say “let me just show you a trick with taping”, she might throttle someone. Except I’m not entirely sure it was a joke. We were all incredibly frustrated. That level of control was applied to every aspect of anaesthesia throughout the rotation. I don’t know how we were expected to learn from our mistakes and correct them.

One time I offered to clip a dog’s nails and after a good five minutes of convincing the nurse that I was, in fact, capable of performing such a hazardous task, she eventually relinquished the clippers. She returned a while later to ask whether I’d made any bleed (no), if I was sure (yes), if I’d clipped them short enough (yes), whether I remembered to also cut the back nails (yes) and whether I also clipped the dew claws (yes). She then inspected them all herself before saying “not a bad effort” and walking off. NOT A BAD EFFORT!? Just about the time I’d recovered from that incident, she returned to give me a 15 minute lecture about how to appropriately assemble an e-collar. Sigh.

Micromanaging aside, the staff were more than happy to explain things and answer questions, so I focussed my two weeks on learning the theory, rather than improving my practical skills. We were encouraged to create an anaesthesia plan specific to each of our patients, including drug choice and dose rate for premedication, induction, maintenance and analgesia, a fluid rate, and specific anaesthetic considerations. This was a really useful exercise, even though the clinicians always used their own plan regardless. We also had an assignment for which we had to come up with a pain management plan for two provided cases, one acute and one chronic. My acute case was a horse undergoing colic surgery and my chronic case was a dog with hip osteoarthritis. I didn’t realise just how complicated pain management could be until I started researching drug efficacy, dose rates, interactions and adverse effects.

As the days passed and we learned more and more about patient physiology, anaesthetic machines, the drugs at our disposal and their endless side effects, it became evident that anaesthesia could be renamed ‘1001 ways to kill your patient’. Strangely enough, incorrect catheter taping technique is not one of them!

The hospital anaesthetic machines and monitors were next level. The most extreme of which I was told is “the only one in the country”. The 10 screens were filled with all sorts of unnecessary numbers, graphs and settings, all beeping and flashing to indicate one thing or another. It’s a good thing the patients were stable, because by the time I found the heart rate and determined it to be dangerously low, the patient could already be dead! I’m exaggerating, of course, but I still found it absurd. Despite being the fanciest anaesthetic monitoring machine in Australia, it seemed to struggle with a basic heart rate and blood pressure reading. Oh the irony! Give me a stethoscope, thermometer and watch any day!

One of the perks of the anaesthesia rotation was that I got to follow my patients all over the hospital and visit friends in primary care, imaging, medicine and surgery. I also got to see some pretty interesting procedures including orthopaedic surgery, CTs, rhinoscopy, surgery to remove an enormous abdominal mass from a tiny dog (the mass was 20% of the dog’s body weight), ectopic cilia removal, a cat that was bleeding into its abdomen, two pig speys, and a horse that was having a fetlock arthroscopy.

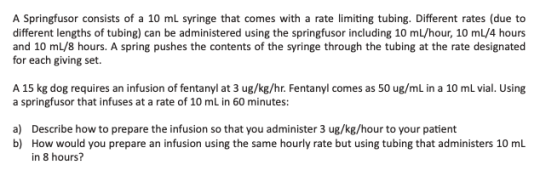

On the final Friday we had a theory exam and three practical exams. The first practical exam involved setting up an anaesthetic machine for a specified patient, leak testing it and fixing a leak. Mine had a hole in the reservoir bag. The second was intubation, which was easy. The third was dose calculations, which I had no problem doing at home, but the exact moment my timer started in the exam, a loud BANG-BANG-BANG started across the room. All I could think was how loud the banging noise was and how fast the timer was ticking down. I managed to get to an answer but I’m not sure if it was right. I’ve added a practice question below, for your enjoyment.

Although I’m now confident with the basics required in every day private practice, I feel as though I’ve only just scratched the surface of anaesthesia. I have my whole career ahead of me to keep learning!

Post link