#bad feminist

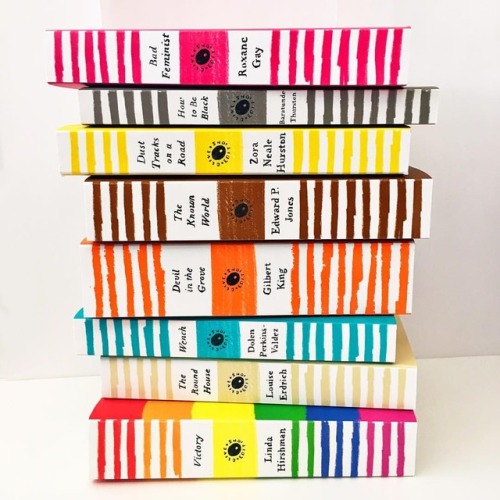

Happy Olives Day! Our limited edition 2017 #OliveEditions are now on sale, get them while they last! (at Harper Perennial)

Post link

We’ve been a bit quiet lately but we’re coming back with a bang:

2017 OLIVE EDITIONS ANNOUNCEMENT!

On sale October 10, 2017 for a limited time; head on over to our Olive Editions page for more info!

Devil in the Grove by Gilbert King

Dust Tracks on a Road by Zora Neale Hurston

How to be Black by Baratunde Thurston

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

‘Books are often far more than just books’ writes Roxane Gay in her essay ‘I Once Was Miss America’. This statement rings true to me when writing this blog post and epitomises why I want to use this book club to discuss important issues. The meanings and implications that many of the books I have read have helped shape my perspective of the world. ‘Bad Feminist’ was one of these books, as I first read it a couple of years ago when I was beginning to discover feminism as something that aligned with my beliefs, but was fearful to outright call myself a feminist in fear of ‘getting it wrong’. This book allowed me to realise that I could still be a feminist even if some of my past and present habits did not align with my beliefs, as long as I was working on improving these things. As the last line of the book states, ‘I would rather be a bad feminist than no feminist at all.’ ‘Bad Feminist’ is very accessible, not only because of its conversational voice throughout but because of Gay’s complete willingness to admit that she is far from the ‘perfect feminist’, if such a thing really exists. The book also begins with the claim that feminism is flawed ‘because it is a movement powered by people and people are inherently flawed’. This is important to remember, especially for people who are quick to denounce feminism, and the statement allows a reader who is sceptical of feminism to find a middle ground with Gay, perhaps making them more willing to listen to what she has to say. ‘Me’ The first set of essays have a confessional tone, as does much of the book, as Gay, amongst various other things, goes into detail on her competitive scrabble wins and losses. These essays are humorous and portray Gay as relatable and charismatic to the reader, allowing her to discuss the hard-hitting issues this book is about whilst remaining approachable to the reader. This aspect of the text makes ‘Bad Feminist’ a really great book for someone who is still finding their feet as a feminist and is perhaps feeling overwhelmed, and Gay’s discussion of popular culture would also be useful for this reader as it is something most people can use as a reference point and reflects how the promotion of intersectional feminism is still absolutely necessary. My favourite essay from this section is ‘Peculiar Benefits’ as Gay discusses the necessity of acknowledging privilege but the dangers of completely silencing those with it, which would create ‘a world of silence’. She claims: ‘we need to get to a place where we discuss privilege by way of observation and acknowledgment rather than accusation’, which is crucial as I have witnessed how excluding individuals from conversation has dwindled discussion rather than encouraged it. ‘Gender and Sexuality’ These essays have an autobiographical format, which allows Gay to use her own experiences to discuss gender and sexuality, whilst also considering their portrayal in popular culture. In ‘How We All Lose’ Gay denounces the view that women should be grateful because of the progression of our position in society over the last 100 years, stating, ‘better is not good enough, and it’s a shame that anyone would be willing to settle for so little.’ As a woman who has been told that the cat-calling that makes me feel physically sick from vulnerability should be taken as a compliment, I can vouch for the fact that just because our rights have improved, we are yet to gain total equality. Gay states ‘if the patriarchy is dead, the numbers have not gotten the memo’ and, from my experience, neither have the men who shout sexual remarks at a women walking home alone at night. ‘The Careless Language of Sexual Violence’ is an essay that explores how damaging the casual ways in which we deal with rape can be, from living in a time that ‘necessitates the phrase rape culture’ to it’s gratuitous portrayals in television and film. Gay discusses how language is often used to ‘buffer our sensibilities’ from the brutality of sexual assault, leading to sympathy for the perpetrator and isolating the victim. This is something that is hugely relatable for me as someone who would shrug my soldiers when I was sexually assaulted at gigs saying things like, ‘they only pinched my bum, it’s not a big deal’ whilst feeling completely uncomfortable for the rest of the night, Even at a gig around a year and half ago when I spent the last two songs being grinded on and groped despite my clear unease and efforts to move away leading me to leave the gig early, I refused to accept to myself that I had been sexually assaulted and even attempted to make up excuses for the perpetrator in my head. Being sexually assaulted felt a great deal more significant than being ‘felt up’ but had I immediately accepted that that was what had happened to me, I know it would have been much easier to remove any responsibility for what happened from myself. This essay does a great job at bringing the importance of the language around sexual assault to light that, as Gay states, is not just careless but criminal. In ‘Beyond the Measure of Men’ Gay discusses how the actions of women are often compared to and measured against those of men and portrays the prevalence of this this through certain books written by women being labelled as ‘women’s fiction’ but similar books written by men being simply fiction for everyone. She states ‘narratives about certain experiences are somehow legitimised when mediated through a man’s perspective’. This is something that I had never considered but found really interesting as a book-lover. In the essay ‘Some Jokes Are Funnier Than Others’ Gay considers the humour behind rape jokes. She concludes that they not only serve to remind women that their bodies are open to legislation and public discourse but also that it is because sexual violence is embedded into our culture so deeply that people feel comfortable in making these jokes. Gay talks about her experience of rape in this book and, for me, her story alone would be enough to make rape jokes unfunny and completely insensitive. She also explains why women are allowed to respond negatively to misogynistic humour, ‘We are free to speak as we choose without fear or prosecution or persecution, but we are not free to speak as we choose without consequence.’ The final essay I’m going to discuss from this set is ‘Blurred Lines, Indeed’ as it discusses how music and feminism are linked - something that is particularly relevant to Girls Against. She looks at how rape culture is embedded and accepted in popular music such as in Robin Thicke’s ‘Blurred Lines’ that ‘revisits the age-old belief that sometimes when a woman says no she really means yes.’ Gay comments on how the culture that supports entertainment that objectifies women also elects lawmakers who work to restrict reproductive freedom. Gay describes this as a ‘chicken and the egg’ situation and as ‘trickle-down misogyny’. If we cannot deduce whether it is the lawmakers influencing the media or the media influencing the lawmakers should we really be willing to treat these songs as insignificant? ‘Race and Entertainment’ The next set of essays are significantly shorter, seemingly because they are much more focussed and specific than the previous set, as Gay discusses how race is portrayed in entertainment through considering various films and their significance. The first essay is centred around The Help and Gay’s take on a film/book that I initially enjoyed was really interesting and helped me to see it in a different light. She explains how The Help is a white interpretation of the black experience and is ‘an unfairly emotionally manipulative movie’, offering us a ‘sanitised’ picture of the early 1960s portraying life as hard for white women, and slightly harder for black women, when in reality life for black women was immeasurably more difficult in segregated America. Gay also describes the black women in this book and film as ‘caricatures…finding pieces of truth and genuine experience and distorting them to repulsive effect.’ After reading this essay I can see that this film that I initially enjoyed was seemingly created for the purpose of enjoyment alone. It uses real historical events that are distressing to provide entertainment and not to truthfully portray the painful history of black Americans because if this were the film’s purpose, an accurate depiction of their experiences would have undoubtedly been more of a priority. Gay feels similarly about Django Unchained, a film that I have not seen and so have less authority to comment on, describing it as ‘obnoxious’ and ‘indulgent’ as Tarantio uses a traumatic cultural experience to ‘exercise his hubris for making farcically violent, vaguely funny movies that set to right historical wrongs from a very limited, privileged position’. She also touches on the Oscars and how ‘Hollywood has very specific notions about how it wants to see black people on the silver screen’, as critical acclaim is often dependent on black suffering or subjugation. She asserts that despite this, audiences are ready for more from black film and I certainly agree with this- there is a great deal more to black experience and history than slavery. In a further essay ‘The Last Day of a Young Black Man’ Gay discusses the detrimental effects of demonising young black men in contemporary cinema in reference to the shooting of 22-year old, defenceless Oscar Grant. The effects of the demonisation of young black men in society are terrifying and Gay’s examination of how this is reflected in film is harrowing. Orange Is The New Black is the subject of the last essay in this set ‘When Less Is More’ as Gay explains how its source material concerning a privileged white woman serving a prison sentence will never be anything more than this. She also states that ,as black woman, she is tired of feeling like she should be grateful ‘when popular culture deigns to acknowledge the experiences of people who are not white, middle class or wealthy, and heterosexual’ and that the way in which we are focussing on OITNB’s attempt at doing this shows the extent to which we are forced and willing to settle. ‘Politics, Gender and Race’ These seven essays cover a broad range of issues and are much less focussed than the previous two sets. In the first essay ‘The Politics of Respectability’ Gay discusses the danger of encouraging respectability politics, stating that the targets of oppression should not be wholly responsible for ending that oppression. She uses examples to portray the problems in suggesting that just because one person from a marginalised group has been successful this does not mean everyone is able to reach this same level of success. This is an interesting essay that shows the many ways in which different groups of people can be diminished and the difficult consequences of this. In perhaps my favourite essay of the entire book, ‘The Alienable Rights of Women’, Gay discusses reproductive healthcare and why it is so important to women’s freedom. Repeating the phrase ‘Thank goodness women do not have short memories’ throughout the essay, Gay explores how trivially reproductive freedom is discussed by certain politicians and why the ongoing debate surrounding it, usually instigated by men, is ‘the stuff of satire’. People have actually questioned me on why reproductive healthcare is a women’s rights issue and although I usually have a long and detailed answer to this, Gay sums it up neatly, ‘There is no freedom in any circumstance where the body is legislated, none at all.’ ‘The Racism We All Carry’ explains how racism is embedded in pretty much all of us because ‘We’re human. We’re flawed. Most people are simply at the mercy of centuries of cultural conditioning.’ Gay comments on the fact that for many people, there are times when you can be racist and times when you cannot, depending on your company and setting. Sadly, I feel this is true for a great deal of people, proving Gay’s previous point. ‘Back To Me’ In the final set of essays, Gay plainly states that she ‘falls short as a feminist’ and describes the ways in which she does. Not only this but she describes how feminism has been ‘warped by misperception’ and that her main issue with it is that it ‘doesn’t allow for the complexities of human experience or individuality.’ Gay’s rejection of a prescribed form of feminism is really what makes her approach so accessible. She concludes in stating that although she might be a ‘bad feminist’, she is committed to the issues feminism promotes despite its issues and that it’s importance and necessity cannot be denied. I enjoyed reading ‘Bad Feminist’ this time round as much as I did reading it for the first time, however there are some small issues I have with it. Gay’s complete acceptance in sometimes falling short as a feminist and straying from the principles that she believes in provides reassurance for the reader but perhaps too much leniency. It’s okay if some of your habits don’t completely align with your views but I think rather than completely accepting it, it’s important to work on changing them and improving yourself and Gay’s approach is often a little too laidback for me. I would have also liked Gay’s essays to have been more focussed on the topics they were supposed to be centred around according to the sub-heading they were under. Although I enjoyed the essays themselves, I felt like the way in which they were organised into sub-headings was a little bit lazy and last-minute and this is especially relevant to the penultimate set of essays, ‘Politics, Gender & Race’. Despite these arguably minor issues I took with the book, I think it is great because it covers such a wide range of topics in an informative, thought-provoking way and I would recommend it to feminist newbies and veterans alike, so much so that I rated it 5 stars on Goodreads, which is rare to say the least! If you can’t get hold of the book, many of her essays are available online including some of the ones I have mentioned. For the month of August, the Girls Against Book Club will be reading ‘The Color Purple’ by Alice Walker. If you aren’t familiar with this feminist classic, it’s a novel, first published in 1982, set in rural Georgia that focuses on the life of women of colour in the 1930s. I’ve wanted to read this book for a while and I hope that you will join me in reading or re-reading it! If you do have any thoughts on ‘The Color Purple’, the Girls Against Book Club would love to hear them and we will feature any comments we particularly enjoy in the September blog post. You can send them to us any time before Sunday 3rd September using the hashtag on twitter #GABookClub, email us at [email protected] or join our GoodReads group and contribute to the monthly book discussion here. All credit to the wonderful Alice Porter