#battle of fishguard

Hello. We’ve been writing this blog every day for a little over eleven months now. As it was our intention to find out why every single day of the year is BRILLIANT, we’re almost there and it seems appropriate to begin some sort of countdown. If we make it, there will be nineteen more posts after this one. You can also find this blog on Wordpress, along with a short explanation of how it came about, and in which we reveal which of us has actually written all of this. Thank you all for reading, liking and reposting.

Why February 25th is BRILLIANT

Mission Impossible

Today we want to tell you about the last invasion of mainland Britain. It was not, as you might think, at Hastings in 1066. That was the last successful invasion. There was one in 1797 that did not go so well. It happened as Fishguard in Wales. The invading army was French and they were led by an Irish American named Colonel William Tate. In the accounts we’ve looked at, there is some discrepancy over the date of their surrender, but our favourite part of this story first appeared in the London Gazette on February 25th 1797, so we’ll go with that.

The invasion was part of a planned three pronged attack on the British Isles. The first invasion would take place in Ireland. Fifteen thousand troops would land at Bantry Bay and they would support the United Irishmen in their battle to overthrow British rule. In order to draw British troops away from Ireland, they would launch two further invasions in what they perceived to be places where they would find the most support. One at Newcastle and another near Bristol. The Irish contingent arrived off Bantry Bay on December 21st 1796, but there was such a terrible storm that they couldn’t land. The Irish didn’t know they were coming, so there was no one to help them. They decided to sail home again.

For some reason, the rest of the plan went ahead. Five thousand troops set off in barges for Newcastle, intent on destroying the collieries and shipyards. They were forced to return to Dunkirk because there was a mutiny. But still the planned invasion of Wales went ahead. Colonel Tate had fourteen hundred men for his mission. Six hundred of them where troops that Napoleon had felt were best left behind when he went off to invade Italy. The other eight hundred were made up of Republicans, deserters, convicts and Royalist prisoners. They called themselves ‘La Légion Noire’ after the dark coloured uniforms they wore. The uniforms were actually ones they had taken from British Redcoats and dyed a very dark brown. With no support coming from Ireland or the North of England, it’s hard to see why it went ahead at all. It does look a little bit like whoever was in charge was just trying to get rid of La Légion Noire.

Four warships sailed from France under the command of Commodore Castagnier. Like the fleet bound for Ireland, they also found the weather was against them and they had to change their plans. In the early hours of February 23rd they landed near Fishguard, but they had already been spotted in the Bristol Channel. The troops and their ordnance were all taken ashore, everyone agreed that the invasion had definitely happened and Castagnier sailed away with the happy news, leaving them to get on with it. Meanwhile, the Welsh were gathering an opposing army. One of the commanders was at a ball, a whole troop happened to be at a funeral nearby. They all set off for Fishguard.

Colonel Tate lost control of a significant proportion of his troops pretty much as soon as they landed. They deserted and set about looting local villages. In Llanwnda, they broke into a church. They used the Bible to light a fire and then heaped the church pews on as well. If they were hoping to find support for their invasion among the Welsh, they certainly weren’t going the right way about it. Discipline was also not helped by the fact that the French soldiers had also discovered that the locals had a large stash of wine. They had it from a Portuguese ship that had been wrecked nearby only a few weeks before.

The Welsh troops were small in number, but they never let on. There were outnumbered by the French about 2-1. Villagers from the surrounding countryside poured in to Fishguard with crude weapons of their own, and one in particular, who we’ll mention in a minute. The Welsh decided to attack before dusk, but the French had an ambush lying in wait for them. Luckily, when they were only a few hundred yards away from lots of armed French soldiers hiding behind a hedge,. They decided it was getting a bit dark and headed back to town.

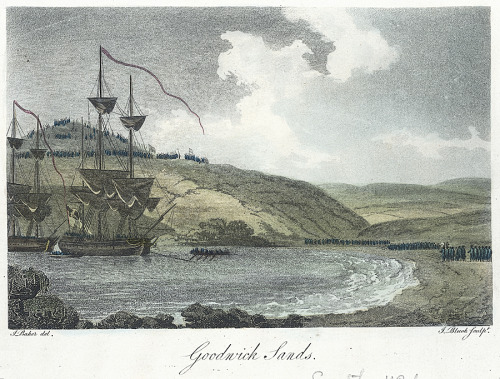

Things weren’t going Colonel Tate’s way at all. He tried to negotiate a conditional surrender. The Welsh said no, they had thousands of people on their side and they would definitely all attack if the French did not surrender unconditionally by 10 o'clock the next day. The ruse worked and Tate did surrender. Part of the reason may have been that the French, rather than being a feared enemy, had made themselves something of a local curiosity. The two sides had arranged to meet on the beach at Goodwick Sands the next day and rather a lot of people turned up to see what would happen. They stood on the cliffs above the beach. Among them were hundreds and hundred of Welsh women. Welsh women were, in those days, inclined to wear bright red cloaks and large black felt hats. This possibly made them look, from the beach, like hundreds and hundreds of British Redcoats.

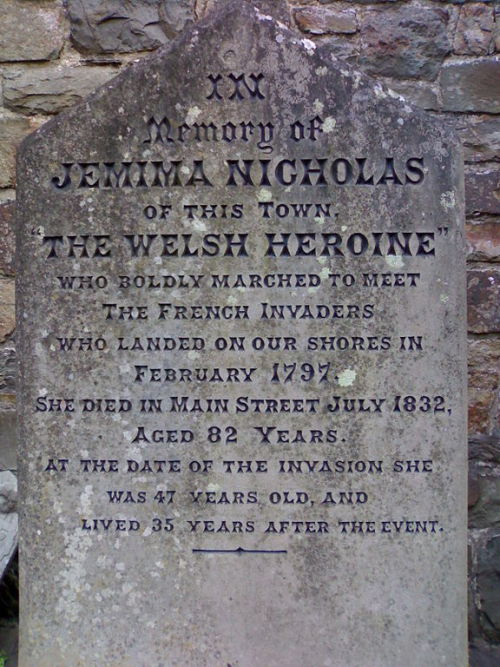

The peace treaty was signed on either the 24th or 25th of February, but a report certainly appeared in the London Gazette on February 25th. It carried the story of Jemima Nicholas, the wife of a Fishguard shoemaker. She was either 47 or, according to more recent evidence 41. She took a pitchfork and single-handedly rounded up twelve French Soldiers and locked them up in a church and then set off to find more. For this, she has been given the name 'Jemima Fawr’, which means Jemima the Great, and a place in Welsh history.

Post link