#becauseofyuri

The Day I Read Aloud to Yuri Kochiyama

I didn’t meet Yuri Kochiyama until three years ago. By then, she was a few weeks short of her 90th birthday, living in an assisted living facility and no longer making public appearances. I was lucky. This summer, the renowned Japanese-American human rights activist passed away on June 1 at the age of 93.

For more than a decade before I ever shook her hand, Yuri Kochiyama had a huge influence on me. During my early years, as I tried to figure out my place in the prison justice and abolitionist movements of New York City, I was often the only Asian in the room. I didn’t know any other Asian involved in anti-prison organizing nor, did it seem, did any of the black, brown or white people with whom I connected. Sometimes, it felt like people were wondering why I was trying to be involved with anti-prison organizing instead of, say, organizing against anti-Asian violence or for the rights of Chinatown restaurant workers. Others were more hostile. The decade had started with the shooting of a 15-year-old black girl by a 51-year-old Korean grocer and, several years later, distrust and hostilities had yet to heal. Feeling as if I were lumped into the same category as the trigger-happy grocer made me feel like an unwelcome intruder at more than a couple of events. But still, I persevered, seeking out people and groups that didn’t automatically make assumptions based on my ethnicity. In part, this was because of Yuri.

Yuri Kochiyama still lived in New York City in the 1990s. I didn’t know her, nor did I travel in any of the same circles, but I knew that she existed and was, at least in my (teenage) mind, somewhat of a legend. Here was an Asian-American woman who had been working for prison justice for longer than I’d been alive. People respected both her and the work that she’d been doing. While we never organized (or even were in the same room) together, I’m pretty sure no one gave her a side-eye glance as if to silently ask, What is she doing here? This was Yuri Kochiyama, the woman who had lived through a Japanese internment camp during World War II, been a part of Malcolm X’s burgeoning Organization of Afro-American Unity and cradled him in her lap as he lay dying on the floor of the Audubon Ballroom. In addition to all that political activity, I also knew she had children and had raised them all to be political people as well. (I wouldn’t learn the magnitude of this until years later, when I read her memoir.)

So, even though I had never met her, I was inspired by her example.

In 1998, there was a march in Washington, D.C., demanding freedom for all political prisoners and prisoners of war in the United States. A bus of Asian-American activists supporting political prisoners was organized to leave from New York City. While the 4 a.m. sky was still dark, I boarded that bus with dozens of other Asian-American activists, including Yuri Kochiyama. That day, I was too shy to approach her, or to even talk to anyone I didn’t know, but it was obvious how respected and loved she was.

Hours later, we piled off the bus under a very sunny D.C. sky. As the 77-year-old Yuri slowly walked towards the action, people approached her, offering her wide smiles, adulation and teddy bears. (Over 10 years later, I learned that Yuri was known for her collection of K-bears, short for Kochiyama bears, that began as her children grew up and left home in the 1970s.) She accepted them graciously and continued to make her way towards the march.

That was my almost-encounter with Yuri Kochiyama. It was over a decade before I saw Yuri again. In those in-between years, I met other Asian Americans who were involved either in social justice organizing that sometimes intersected with anti-prison work or who were deeply involved in prison justice work. I also felt less hostility (or maybe I just grew a thicker skin) when I was the only Asian face in the room.

Fast forward to 2011. By then, I’d become a mother, become obsessed with finding the hidden histories (or herstories) of resistance and organizing in women’s prisons, and graduated college (in that order). I’d taken some of those hidden herstories I had uncovered and turned them into a book, then I’d gone on what I jokingly referred to as the Never-ending Book Tour. Although my book had been published in 2009, I was still on the Never-ending Tour two years later when I was in the Bay Area talking about women’s incarceration — specifically women imprisoned for self-defense and the movements that emerged to defend them. I also learned that my Never-ending Book Tour and other publicity efforts had led to my book being sold out. My publisher asked if I would do a second edition, which required new material.

In between book-related events, I made plans with a friend from the 1990s. He had been one of the Asian-American activists who had organized with Yuri and her husband, Bill, when they had lived in New York City. After moving to the Bay Area, he became the person who took on the responsibility of driving Yuri from her assisted living facility to wherever she needed to go. “Would you like to have dinner with Yuri Kochiyama?” he asked as we tried to make plans.

Would I? Really?

Even as an adult, I still get tongue-tied when in the presence of people who are considered movement superstars and, in my mind, Yuri Kochiyama was a huge movement superstar. I wasn’t sure if I would actually think of something to say to her, but I wasn’t going to pass up the opportunity to sit down to dinner with her. So off I went, with a copy of my book under my arm as a present.

We drove to her assisted living facility. Many of the residents recognized my friend from his frequent visits and greeted him by name as we walked down the hall to the elevator leading us to Yuri’s room. In my excitement at meeting the famous Yuri Kochiyama, I didn’t pay much attention to my surroundings.

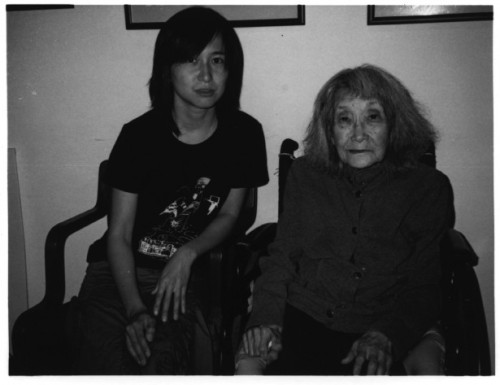

Then we were out of the elevator and in her room. My friend introduced us, and she immediately welcomed me as if I were the celebrity. If she had no idea who I was, she definitely didn’t let on. Perhaps she was used to meeting young(er) Asian-American activists who were in awe of her. Perhaps she was used to putting these awe-struck fans at ease. Instead of waiting for me to stumble my way through starting a conversation, Yuri immediately began to ask me questions. Our entire conversation was filled with talk about women in prison, questions about why I was in the Bay Area, and a discussion of the piece I had written about women incarcerated for self-defense in the 1970s. She was also excited to know that we had other mutual friends in common from the long years of working around prison issues.

When we arrived at her daughter’s house, my friend suggested that I read parts of my book to Yuri. Although Yuri had been working around prison issues since before I was born, she was still horrified by the conditions I described, exclaiming, “Those poor women!” or “How terrible!” Sometimes, she looked as if she would cry at the litany of abuses and injustices I was reading out loud to her. I felt terrible that my book was depressing her. Somewhere between her second and the 20th exclamation, I decided that my second edition needed a chapter dedicated to stories of resistance, a section that could serve as a good read-aloud portion and leave the reader (or listener) with a sense of hope rather than sadness and futility.

Even before I spent that early evening reading aloud to Yuri Kochiyama, I knew that I wanted to write about resistance and organizing against horrific prison conditions. But the experience of reading to her — and inwardly cringing that my book was causing her distress rather than offering hope — strengthened my determination to seek and write about histories and herstories of prison resistance and organizing. The following year, the second edition of my book came out, including that chapter inspired by Yuri. Now, three years later, I write weekly pieces about resistance and organizing and, motivated by that evening, I continue to seek out stories that inspire and rouse us to action.

Victoria Law is a freelance writer, analog photographer, and parent. She is the author of Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women andco-editor of Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind: Concrete Ways to Support Families in Social Justice Movements & Communities.

This post originally appeared in Waging Nonviolence.

Post link

Yuri was here

but

nothing

marks her birth

no nation

honors her death

so they made their own

testimony

of the life lived

the generations rebirthed

the children raised

the voices spurred

the borders crossed

the liberation sought

the evidence that she lived large

to scream that she stayed true

to show that she moved us forward

because it pains to see

our giant

leave without a trace

ignored or forgotten by most

but

cherished by those

who keep on

keepin’ on

Keepin’ the struggle alive

even when they mourn

when they decided

to gather memories

to commemorate her life

to celebrate her fight

on their own

they did just what

Yuri would do

if she were still here

Rest easy, Mrs. Kochiyama.

Jason Fong is a high school student at Redondo Union High School interested in Asian American issues.

I discovered Yuri and the inspiring Asian American movement activists like her at a time when I felt my identity didn’t matter, when it was ridiculed and I didn’t understand why. Now I do and I couldn’t understand why a dumb reason like the way I looked made me a victim. Like so many others like her, she taught me I’m not a victim and my identity meant something. So, I make this heartfelt declaration: please don’t let her memory, or any of the other Asian American movement leaders, fade away into nothingness.

Ralph Le

Yuri Kochiyama’s life and legacy is a reminder to Asian Americans and to all those who believe in social justice, of a basic value: to show up whenever and wherever injustice occurs and to engage in acts of resistance and solidarity. She did just that throughout her life. I remember how she became a strong voice to highlight the experiences of South Asians, Muslims, Arabs and Sikhs who faced discrimination in the aftermath of 9/11. Film director Jason DaSilva captured Kochiyama relating the post 9/11 dragnet of detentions and deportations to the experiences of Japanese Americans – including her own – who were interned during World War II. It wasn’t surprising that Kochiyama would make these connections. She had been an ally in key moments of struggle before, whether it was supporting political prisoners, calling for the establishment of ethnic studies programs, allying with the Black Power movement, or demanding Puerto Rican sovereignty.

Deepa Iyer is the former director of South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT) and a writer and activist.