#contemporary ya

Growing up male in America, there were many damaging things I learned about being a man. Society taught me some of these things explicitly, while others were implicitly made clear through potential consequences that were a constant threatening undercurrent. The one I want to discuss here is the one I find myself thinking about a lot these days as a high school teacher and a writer of fiction for young adults: the lie that boys do not feel deeply, that we are simply hard-wired to be insensitive.

Society constantly bombarded me with this lie even as I knew it wasn’t true. As a kid, I cried easily. I enjoyed poetry and reading. I loved cuddling stuffed animals. I felt bonded to pretty much any living thing I came across (or even any inanimate object if given a name). But as I grew older, I received the message loud and clear that these were not aspects of myself I should embrace publicly, or I would be labeled as “gay” or a “pussy” and then suffer the social consequences. Of course, as a kid I didn’t have the ability to deconstruct the homophobia and misogyny inherent to this limiting view of masculinity and the wider damage caused by buying into it. I didn’t have the self-esteem to be my actual self. Instead, I downplayed all of those “softer” sides. I learned to stop crying, to hide my stuffed animals, to avoid emotions outside of humor and anger. I emphasized the sports I played and the girls I wanted to get with. So it was not that as a male I did not feel things deeply, but that I became an expert of suppression.

As a result, I never lacked for friends, which I suppose was the point of conforming. But, even so, I was always lonely. I never felt very close to any of the guys I hung out with in my middle school or high school years no matter the quantity of time we spent together. I believe they were also buying into the same lie as me—a lie even more strongly messaged to boys of color—so there was this collective unspoken agreement to never talk about anything too real, anything that would expose our softness. Instead, we played—sports, video games, music, etc.—because to play was to distract ourselves, to make us believe our friendship was deeper than it was. Yet I always wondered how many of us were secretly lonely, how many of us dealt with that loneliness in damaging ways.

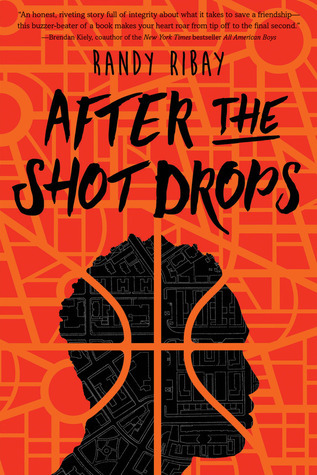

I think this is why when I write YA fiction, I gravitate toward exploring friendship among boys, and particularly boys of color. This is why my characters are, at their core, lonely. After the Shot Dropsbegins with Bunny and Nasir each in isolation, struggling with the fallout of Bunny’s decision to transfer schools. Their issues are grounded in this loneliness, and it seems so obvious that they could resolve their problems if only they knew how to communicate honestly, to be vulnerable with each other. But the challenge here as a writer of realistic fiction is the challenge of real life: how do they overcome all of the societal programming that pressures them to do the exact opposite?

As many writers of children’s literature, I believe that fiction can serve as a roadmap. It can be countercultural, can be a form of resistance that shows readers another way to exist. A better way, a more freeing way. That is what I hoped I have done with Nasir and Bunny, and it’s what I hope to do with my other stories as well. I consider myself lucky to be writing at a time when so much of what I’ve struggled with in silence is now part of the national conversation, and I’m proud to be writing alongside so many other young adult authors who are trying to dismantle these toxic ideas. InThe Fire Next Time, James Baldwin writes, “Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” I am hopeful that these stories will help our boys figure out how to remove their masks in order to construct a healthier masculinity.

Randy Ribay is the author of An Infinite Number of Parallel UniversesandAfter the Shot Drops. He was born in the Philippines and raised in the Midwest. A graduate of the University of Colorado and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, he is a high school English teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area where he lives with his wife and two dog-children.

After the Shot Drops is available for purchase.