#dilshad qadir

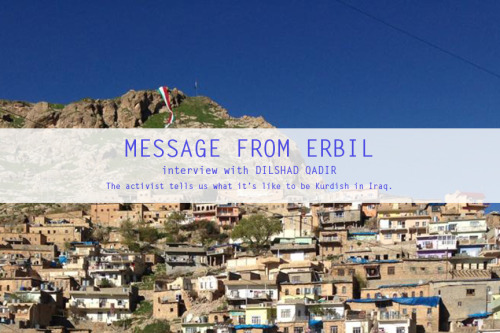

Dilshad Qadir is a Kurdish activist from Erbil, the capital of the autonomous Kurdistan region in northern Iraq. The region is full of different ethnic and religious groups, and he’s worked among them on democracy, human rights, and peaceful coexistence for 15 years. We talked to him about daily life in Erbil, what it means to be Kurdish and Iraqi, and his hopes for the future.

Dilshad Qadir.

From the west, it can be hard for us to understand daily life across the Middle East. What is daily life like in Erbil?

Well the downtown area of Erbil is very interesting. At night there are lots of activities, cafés and restaurants. Most people meet friends for a coffee or shisha. When the weather is nice, people take weekend trips to the mountains.

But to be honest, since 2014—when ISIS took major areas in Iraq and the Iraqi Civil War began—the current situation has been on everyone’s minds. Before then, there was hope for the region. Now there’s not much hope: there is so much killing with ISIS, there’s an economic crisis, and there’s no national leadership: the government and international organizations are sectarian. People are focused on finding opportunity or leaving the country.

There is actually a really popular TV show that deals with these issues. It’s called Bezmi Bezm. It’s a weekly sketch comedy that’s comments on the social, economic, and political issues. It’s quite funny, and has become very popular in the past year. You hear the jokes on the street and things like that.

You mentioned sectarian divides in the government. But how do different ethnic groups interact in Erbil in everyday life?

There’s a lot of diversity in Erbil. Of course there are Kurds, but also Yazidis, Iraqi Christians, and Iraqi Arabs from the southern part of the country. Kurdistan is relatively safe, and last year, over a million people came to Iraqi Kurdistan from the Sunni conflict area just south of us. There are also people from around the world working at the international organizations and companies.

Mostly, it’s a respectful, peaceful place: everyone is interacting, in the same neighborhoods, going to the same stores. There might be some tension sometimes, but nowhere near full-scale conflict. People outside of the Middle East have this picture that we love killing, and it’s not true. We are human beings, and we’re very kind people.

A market in Erbil. Photo courtesy of Dilshad Qadir.

You’re ethnically Kurdish, but your nationality is Iraqi. How do those identities relate?

To be honest, the majority of Kurds don’t feel Iraqi. This feeling has intensified because the Iraqi government has not supported Kurdistan. Al-Maliki, the previous Prime Minister, cut Kurdistan’s budget. The Kurds supported the new Prime Minister, Al-Abadi, but that was because of pressure from the U.S. We knew the government would not support the Kurds, and it has not. Even now, Kurds in Baghdad are under threat of the Shia militia. So it does not feel like our own country. Outside of the region, Kurds always introduce themselves as from the Kurdistan region, not Iraq.

Kurdistan is a region that spans parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Do Kurds from the different countries feel unified? What are the main differences?

Yes, we feel that we’re the same people, and the main difference is really language. There are two Kurdish languages: Sorani is spoken by people in Iran and northeastern Iraq, and Kurmanji is spoken by people in Turkey, Syria, and northwestern Iraq. Of course, the states that Kurds live in have their own languages and cultures, so that does influence the Kurds that live there. But we are a unified people.

A Kurdish flag flies over hills in Kurdistan. Photo courtesy of Dilshad Qadir.

How do you see multiculturalism affecting the future of Kurdistan?

That’s the question everyone is asking. Before 2014, different ethnic groups were willing to work together under a unified Iraq. But the political system failed to bring security to all the ethnic groups, so now they want independent states. It’s a security issue.

The Kurds have suffered for hundreds of years from different regimes. No one in the region was accepting of an independent Kurdistan. But now, thousands of people from the very groups who attacked us before have been welcomed here after ISIS pushed them them out of their cities. There is hope that now that they have seen us they will understand. Forgiveness is key.

Big question: what do you see for the future of the region?

I try to be optimistic, but it’s becoming really hard. There is so much hopelessness, more than any other time. You spend your day watching the news, you become very sad, you go out to meet a friend for coffee, and you again you talk about the politics. We know the reason there is violence: for control of the resources. I think the game has become clear to everyone.

I was optimistic before 2014. Prime Minister Al-Abadi had a lot of ideas about political reforms, and he had a lot of support. But he failed—the political parties won’t allow reform. I think now it’s hard to envision something united, with different groups coexisting peacefully. I think Iraq will eventually become three states: the Kurdish state, the Sunni state, and the Shia state. Of those, Kurdistan will be the most prepared to be independent. But it will be hard to define those borders, and there will be a lot of external pressure, especially from Iran. It depends on how international leaders align.

However, when I’m working with youth, that’s when I feel the most optimistic. There is always something new, so much life. Watching them grow, going on with new accomplishments makes me happy. You can see your work has an impact. It gives me hope. ✰

See more at confluxmagazine.com

Post link