#hard post sorry

Let’s make some penises in Chinese.

Because there are relatively few characters in Chinese (around 20k in a modern dictionary) compared to the number of words in other languages (100k+ in English), most characters carry many meanings. This leads to ambiguities if writing were to be fully composed from single-character words, which is why most words in modern Chinese are compounded from two or more characters, and the meaning is synthesized from the individual meanings. Here are some penis-relevant suffixes, in no particular order:

-物 thing

-器 organ/instrument

-根 root

-茎 stalk

-棒 stick

-柱 pillar

-具 implement

-刃 blade (ouch)

You’ll notice that these are all, well, things. This is one typical pattern for making a Chinese compound word: the second character describes the physicality in some way while the first describes an attribute (characters are flexible and can be either prefix or suffix depending on context). Here are some penis-relevant prefixes:

巨- huge (the opposite would be 微 for tiny, but it’s hard to find micropenises in erotica)

硬- hard

阴- yin

阳- yang

性- sex

那- that

玉- jade

肉- meat

凶- violent

男- male

Now we can create our own penis euphemism by mashing any two together. Here are some real quotes from explicit Jingsu fanfic (translations are kept literal here, but I almost always translate every euphemism to cock because it’s the English term I hate the least):

阳具 = yang implement

萧景琰的阳具大得惊人,比一般的乾阳还要大上几分,他曾笑说这是皇家威严,被梅长苏白了一眼 [x]

Xiao Jingyan’s yang implement was frighteningly large, even significantly larger than the average Alpha’s. He once joked that this was the might of the imperial bloodline, getting an eye roll from Mei Changsu.

凶刃 = violent blade

只是等到下一个清醒的瞬间,萧景琰已经将他的双腿分开。将那粗硬滚烫的凶刃抵上濡湿的穴口。《踏雪寻梅》

But the next instant he came to, Xiao Jingyan had already parted his legs. Pressed that thick, hard, and searing violent blade against his wet opening.

性器 = sex organ

萧景琰的囊口已经完全开了,里头两根性器探了出来,打在林殊大腿外侧 《四时歌》

Xiao Jingyan’s sac had fully opened, two sex organs emerging from inside and hitting against the outside of Lin Shu’s thigh.

肉棒 = meat stick

他一定不知道自己被黑布蒙住双眼,仰着头费力吞吐男人肉棒的模样有多……诱惑 [x]

He must not know how…seductive he looks, black cloth covering both eyes, tilting his head to strenuously swallow a man’s meat stick.

那物 = that thing

萧景琰也不再磨蹭,随手抓过床边的消毒啫喱,在自己的那物上涂了几下便抵在了长苏紧闭的穴口 [x]

Xiao Jingyan didn’t waste any more time either, grabbing the disinfectant gel conveniently by the bedside, applying it a few times on that thing of his then pressing it against Changsu’s tight opening.

The anatomical term for the penis is 阴茎 = yin stalk, the word that is the closest equivalent of penis. But why is the penis both a yin stalk and yang implement? Glad you asked. Yang is associated with the male and yin with the female, but the very concept of yin-yang is that there’s yin in yang and yang in yin (think of the symbol itself). The penis is a yin part because the privates are the most yin on the body. So you can think of it as either the thing of a yang being, or the yin thing on a yang being—the wonderful duality of the male member.

As you might expect, not all of the possible combinations are actually in use. Like, 阴棒 = yin stick isn’t a thing. Why not? I don’t know, it just isn’t. If you used it in context, readers would understand you mean penis and probably puzzle a bit over why you didn’t use the more common names.

Some of the combinations also mean other things. 凶器 = violent instrument actually means murder weapon in ordinary use. Can it be a penis euphemism during rough sex? Yes, but most of the time it means the real weapon. 那根 = that root is tricky because 根 is a classifier word (a similar concept to measure words in English) for long stick-like objects in addition to its meaning of root, so 那根 is almost always used in conjunction with other words, like that phallic [thing], as opposed to a penis on its own, which would probably be confusing to read. But when the character preceding 根 is something else, like 男- male, then it’s not being used in the classifier context, and 男根 = male root is indeed a penis.

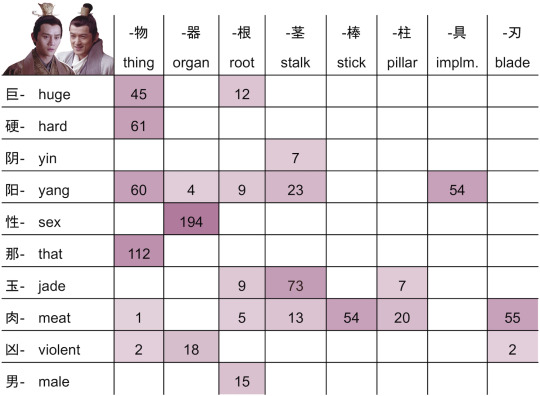

Now that we’ve gotten the explanations out of the way, I searched through the corpus of Chinese Jingsu fics on my computer (around 1000+ fics) to look for all possible combinations of the prefixes and suffixes listed above, tossing out the compound words that don’t mean penis in context, to see what the most popular penises are. Behold the Jingsu compound penis matrix:

Congratulations to our winner, sex organ, and the distant runner-up, that thing. In contrast, the anatomical yin stalk is not very popular, kind of like how penis is not used as frequently as other terms in English erotica.

Okay, so now you have the power to create all kinds of penises. But what’s the correct penis to use in a particular situation? Jingsu smut is, of course, mostly ancient erotica (unless it’s a modern AU), so the tendency is to go for the more literary and euphemistic, and the way to do that is to be less physically descriptive. That thing is definitely more suited for delicate company than meat stick (though some authors happily use meat stick in their ancient settings anyways), and jade/yin/yang penises are also more literary. 玉茎 = jade stalk is, in fact, the traditional Chinese medicine term for the penis and also a literary term, in use for well over a thousand years.

萧景琰取了红帛将梅长苏的玉茎捆扎起来,被白肤衬起来耀眼得很。《梅烬》

Xiao Jingyan tied up Mei Changsu’s jade stalk with red silk, looking quite eye-catching against white skin.

Some more penises

It would be way oversimplifying things to say we’re done now when there are many more methods to form words and penises in Chinese besides our simple algorithm. Let’s first discuss some concepts with English analogs:

A lot of ancient cultures associated chickens with the male member, and we have cock in English. In Chinese, children call penises 小鸡鸡 = little chicken, kind of the equivalent of weewee. You would definitely not use it in a sexy story.

In English you could say he pushed himself inside, and you could say that in Chinese too, with 自己 = self. A relatively euphemistic term.

There’s also little [person’s name], so 小长苏 = xiao-Changsu and 小景琰 = xiao-Jingyan exist. And yes, so does 小小殊 = xiao-xiao-Shu, Lin Shu’s penis. This might be my least favorite one. These are not generally euphemisms you’d see in more…well-regarded erotica.

Okay, now onto the more uniquely Chinese penises. We have some more euphemistic ones:

那话儿 = those words, actually meaning that which we can’t speak of, and penis. 话儿 on its own just means words and remarks in general, but once you add that in the beginning, it becomes a whole other thing (though it can still mean those words in non-erotic contexts). This is one of the euphemisms found in the infamous erotic Ming Dynasty novel 金瓶梅 (Jīn Píng Méi), The Plum in the Golden Vase, so it has a storied history, though it isn’t used much in Jingsu smut at all. 不文之物 = uncivilized thing is also along these lines (之 here is a literary possessive particle). You can also put all kinds of adjectives before 之物 for a more customized penis.

Speaking of adjectives, one thing about Chinese very different from English is that parts of speech are fluid, especially in Classical Chinese where many characters are basically any part of speech. 火热 is fire + hot, but it can be both an adjective, fiery hot, that you stick in front of a penis, or a noun, fiery heat, that acts as a penis itself. So 火热之物, fiery hot thing, is a penis, and here’s an example where just fiery heat is the penis:

他稍顿了顿,便继续往里推进,里面温暖紧致,肠道吸附在他的火热上,就好像他们天生就是一套的,此刻终于镶嵌完整了 《夜宿山寺》

He paused slightly, then continued pushing inward. The passage is warm and tight inside, clinging onto his fiery heat as if they were two pieces made for each other, finally tessellating together and becoming whole in this moment.

We also have words with standard definitions that mean something else in erotica:

尘根 = dust root, which is actually a term in Buddhism that means one of the human senses rooting you to the mortal realm, often referred to as the realm of ephemeral dust (尘世). This is a creative allusion, because what else is a penis but a root that traps you in carnal desire and prevents you from reaching nirvana? Of course, whether it’s appropriate for use depends on whether you want to bring up mortality and the illusion of desire when your characters are getting it on. 孽根 = sinful root, or the more fun translation, root of evil, is also along these lines.

只是这么一想,萧景琰压根还没被触碰到的尘根就一颤一颤的立了起来,硬邦邦地将单薄的亵裤撑起一片帐篷 [x]

At this mere thought, Xiao Jingyan’s utterly untouched dust root trembled upwards, forming a stiff tent in his thin underclothes.

命根 = life root, meaning the source of vitality or reason for living, which is obviously the penis. This one does refer to penis in ordinary use as well, often humorously.

他的命根子给萧景琰含着,用力吮裹,几乎要把他的魂从身体里吸出来一样。[x]

His life root was held in Xiao Jingyan’s mouth and forcefully sucked, as if threatening to extract his soul from his body.

欲望 = desire. Very popular in erotica, not in the dictionary as a penis, and may confuse a first-time fic reader why an abstract concept is being shoved places.

萧景琰握住梅长苏纤长的双腿,让他缠在自己腰上,把快要忍爆了的欲望抵在那小小的入口,慢慢地推了进去 [x]

Xiao Jingyan gripped Mei Changsu’s slender legs, letting him wrap around his own waist, and pressed his desire, nearly exploding with need, against that tiny opening, slowly pushing in.

分身 = split body, or where the body parts (and what you do with it to another body). Its usual meaning is to find time to do something else, and this meaning is only for erotica.

At this point, I should say that some of these may have been invented for erotica to get around censorship. The coined words often evolve to become part of the vocabulary of the in-group over time, such that even when there’s no need to censor, people instinctively use the vocabulary to signal, whether subconsciously or consciously, that they’re in the know.

Of course, just because a euphemism is popular, or of proper ancient lineage, doesn’t mean it will be subjectively to your taste. Jade stalk burns my eyes despite being a classic literary term, which probably says more about my Chinese than anything else; someone who’s really internalized this term and isn’t still on the literal level of understanding probably doesn’t mind it at all. Honestly, my original intention was to giggle a bit at all the euphemisms, but now that I’ve stared at them for a while, they all seem…okay to me (except xiao-xiao-Shu, that one can die). Not sure whether that’s a good thing or not.

A bonus last one very relevant to Jingsu, 龙根 = dragon root, just for His Majesty’s penis.

萧景琰的龙根还埋在自己体内,下体湿滑粘腻,一片狼藉,胸前的两点又被肆意玩弄,梅长苏真想就这么昏过去算了。[x]

Xiao Jingyan’s dragon root was still buried inside him, his lower body slick and wet, a completely sorry mess, and the two nubs on his chest were being wantonly toyed with again—Mei Changsu really wished he could just pass out on the spot and be done with it.

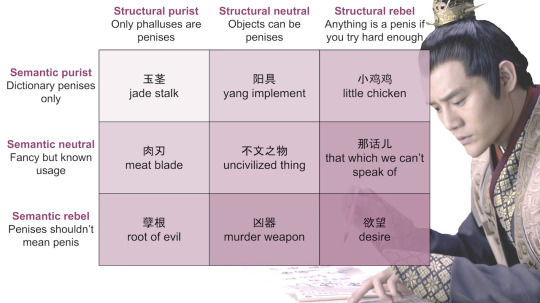

Here’s a penis alignment chart that is almost, but not quite, entirely unlike a summary of our findings:

What if I don’t want to make penises?

As you’ve seen so far, Chinese is very good for euphemisms, and you can write the dirtiest smut without mentioning any parts once.

My favorite Jingsu sex euphemism is easily 梅开二度, literally plum blossoms bloom for the second time, which is an idiom meaning reaching the pinnacle again. It’s frequently used to describe a footballer scoring the second goal in a single match, someone finding new love after a failed relationship, or yes, orgasming for the second time in one night. But in the Jingsu context, it can also be literally read as…Mei Changsu “opens” for the second time.

I would write another post on euphemisms for other body parts and sex in general (including the inexplicably many sex puns in NiF canon names), but this euphemism is clearly the pinnacle, and I will not reach it again.