#indianfeminism

By Meera Seshadri

It’s a new house. I walk through its shadows. Moonlight falls on a picture, and shimmers over a brass lamp, calling me near. The tile is cool beneath my feat. I love dark wood. Teakwood, rosewood. There’s an old grace, tinged with melancholy, that lies just beneath its proud gleam. Wood that carries itself like a Great Grandmother. Family heirlooms watch me knowingly, stranger and friend. High ceilings … and lofty, long-forgotten dreams. Memories I want to push away. And then the tears come.

My house in Bangalore is an old house. I went there for a weekend, not long ago. A bungalow with peeling paint, erratic electricity, and a gray gloom that settles into everything. It has been so, so long since the noise of happiness filled the rooms and floated out onto the verandah. I try my best to bring the house back to life. I fluff the cushions and put them on the swing every morning, only to realize the covers are torn beyond repair. I open the curtains all the way, urging sunlight to warm the walls … but the trees are dense and overgrown, resentful of my eagerness. Heavy padlocks protect rooms and cupboards that haven’t seen the light of day for years. That Sunday morning, I sat out on the swing with a cup of green tea. The lady who sells the flowers walked by the gate, colorful blossoms perched in a straw basket on her head. She eyed me strangely. “Indira? Indira?” she asked. I let her in, and bought two marams of jasmine. I told her I was Indira’s granddaughter, only here for the weekend. With a faraway look in her eye, she reminded me of when the house was filled with women, and my grandmother bought jasmine, marigolds, and “even 10-12 roses”. I remembered.

It used to be so different. Bougainvillea trees and jasmine creepers on the wrought-iron gates, always in bloom. Children playing in the monsoon – hide and seek, dodgeball, lock and key. Grandmothers standing by their gates, calling out pleasantries into the evening. My grandfather in his regal armchair, kettle-cooked chips on the table and a weepy Rajesh Khanna film playing in the background. My hands tracing the zig zags of granite countertops, stealing pakodas and handfuls of murukku from the kitchen. Women hurrying in and out of rooms, armoire doors banging, tea cups clinking, sneaky laughter and morsels of gossip exchanged like hot sweets. A house, all abuzz. My house.

But the best time is afternoon. After lunch. When the women make a big show of clearing away the pots and pans, wiping the table clean, and gathering in the living room under a furiously turning fan. Some women have pillows under their heads, hands clasped over their hearts. Others lie on the carpet and read ‘Anandha Vigadan’, a Tamil magazine devoted to celebrity gossip, articles on “home and hearth”, and general advice to keep yourself fair and lovely all year long. “Put neem on your face,” reads my grandmother. She frowns slightly. “No no … papaya … that is the best fruit for skin,” she decides. I shake my head and sigh happily. Their bellies are full and so are their minds, eyes staring up at a ceiling fan that seems to turn their thoughts and worries around and around and around. Then someone cracks a joke. Another remembers a story. And the room erupts into laughter for a few minutes before we hear a disapproving groan from my grandfather’s room. Shushed smiles. I know he loves the banter … straining his ears to hear our whispers. The quiet takes our minds back to the ceiling fan and the worries, but the laughter makes everything easier.

That Sunday afternoon, I lay on the carpet and stared up at the ceiling fan. But it was just me, turning

around

and around

and around.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Meera Seshadri is a public health professional working at the intersection of sexual health promotion and sexual violence prevention. Although a Bay Area native (and fierce West Coast loyalist!), she has lived and worked extensively across the United States from Atlanta to Washington DC, and abroad in Japan, Nicaragua, the Philippines, and India. She holds a Masters of Science in Public Health (MSPH) in Health Communication and Adolescent Health and Development from Johns Hopkins University, and a Bachelor of Arts in Global Public Health and Dance. Meera is a lover of all things fantastical and unconventional, inspired by the romance of travel, food, dance, and the sea. Follow her on Twitter @MeeraSeshadri

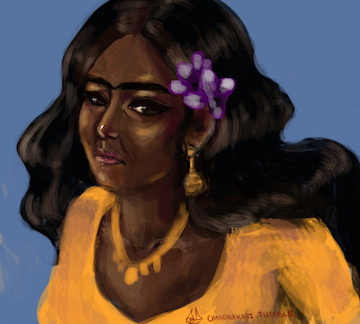

Srutika Sabu is a generation 1.5 Indian-Canadian Malayali. She is a graduate of Rutgers University where she studied biotechnology and transnational feminism. She is currently a New York-based med student who spends her free time on creative projects, especially her artwork. Srutika is on a quest to explore the themes and issues of transnational feminism through her artwork, animation, and identity as an Indian-born diasporic child. She spoke with Sakhi about her passions, feminism, transnational background, and the artists that inspire her. You can check out more of her work here.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your artwork.

I’m a transnational child: born in North India to South Indian parents, I moved to Brampton, Ontario at age seven and grew up there until I was 15. I went to undergrad in New Jersey and now attend medical school in New York. I’ve been drawing since I could pick up a crayon. My art is heavily influenced by the world of anime, manga and video games. In my undergrad I had the privilege of meeting many radical souls, especially radical brown souls and developed an interest in transnational feminism.

How do your medical and science backgrounds interact with your artwork?

I’m still figuring out how to merge my medical background and my art background. I’ve always been a multidisciplinary person. With South Asian parents who come from being educated in the hard sciences I knew almost innately that my parents valued science education, specifically in the fields of engineering and medicine. As a result, I separated my art from medicine.

Having said this, ever since becoming a med student and having classes that just scratch the surface on how to serve different populations, I have been incorporating more science and technology into my work. I have recently started thinking about bodies and how they are often medicalized and seen as deficient and yet medical technology is a great equalizer. I’ve been exploring more sci-fi themes lately, showing images of brown women using technology and also creating it (perhaps it was unconsciously inspired by the many brown women I know who create and use technology on this level, my mother included. Did I mention that she’s also a huge Trekkie?). A recent piece that I finished (the pink one) featured a character with four limbs coding, with one of the limbs having a prosthetic lower arm. I was thinking about how we define a “normal” body and how disabled bodies are compared. I was thinking of how “able-bodiedness” is a temporary state. Thus, inspired by the iconography of Hindu Goddess paintings and sculptures, I was thinking of how different bodies in a society can define different norms. What if there is a society were the norm was to have four arms? And using the technology and being able to live a certain quality of life and with dignity required the use of all four arms? What if you had only two arms? Wouldn’t that mean our two-armed bodies are disabled in the society?

You say that you want to confront the narratives around dark-skinned women and beauty. What are the dominant narratives you see here and how do you work to disrupt them?

In South Asia, we can see the vestiges of colonialism everywhere. It is something as small as thinking that you are educated (not even more educated) if you know English. Or the idea that you are more “modern” if you wear Western clothing. And of course the very prominent idea that the paler you are the smarter, more competent, more modern, wealthier, more feminine (if you’re a woman), higher the caste and the prettier you are. The list of positive associations is quite long. Growing up in India and in Canada (among a predominantly Punjabi community) as a dark skinned South Indian women, I’ve had my share of microaggressions ever since I was four. Examples include the children in my rickshaw rides to preschool telling me my skin was dirty and even going as far as telling my friend that he shouldn’t be friends with me for that reason. I’m fortunate that my parents understood that Indian people come in different shades. But I had a lot of internalized hatred when I was younger. I got my darker skin from my both of my grandfathers, making me feel genuinely unfeminine as all the women in South Asian media had fair skin even as her love interest had much darker skin. I’ve been able to heal since then. Although now, I joke that my greatest fear is that if in the highly unlikely event I beat Malala in bringing World Peace, the popular Indian film industries would get a pale and maybe half-white woman to play me. I do not want to be erased or whitewashed.

People who like my artwork often tell me how important it is that I paint dark skinned women who are gorgeous. I want to capture what Shirley card algorithms (which calibrated cameras’ colour sensitivity to a white woman’s skin) would not be able to get. I’m on a mini mission to create images of South Asian women with darker complexions that question assumptions we have around dark skin. I wanted to imagine a modernity without it being synonymous with Westernization and homogeneity. I wanted to use my transnational feminist lens and use it to create non-Western narratives of development. Whose ideas get to decide what humanity’s future looks like? More specifically, which type of humans do we decide get the right to represent humanity’s future? What shade will they be? What types of bodies will they be? Why must we compare how forwards and backwards other people are according to the West? Why are these comparisons are made using the bodies of brown women? I call this theme Desi-Futurism, a play on a similar genre, Afrofuturism. In addition to this, I was also inspired by anime, particularly ones that use imagery that mixes Japanese culture and sci-fi.

You said you’re interested in the “monopolization of Indian-American identity”. Can you tell us more about that and what it means to you?

I think this can be summarized in a joke by Hari Kondabolu. The punchline essentially boils down to someone asking him “What kind of Indian doesn’t dance to Bangra yo?”, to which he replies “South Indian, son, South Indian.” For kids in the diaspora, we use the word desi to summarize and lump a lot of different cultures of South Asia. I mean even within India there is this exchange and adoption of customs and clothes from other regions. My uncle once joked that the salwar kameez was becoming the national dress now as young women wore the outfit because it was so convenient. In contrast, my mother would tell me stories of how returning from engineering college in the 80’s to Kerala to visit her parents in this very outfit was seen as very indecent as the regional dress for people her age at the times would have been a pavadu (skirt). But even in this instance, local languages and culture is still there and what is Indian culture is defined as is very different. In the diaspora, I often find myself in spaces, especially as a Malayali kid, where the other diasporic kids don’t know that Indian culture is a lot more diverse than they think it is. I’ve had non-Indian people telling me that I’m too dark to be Indian or explaining to me what they think that my culture is.

Recently during Diwali I was thinking of how people need to be aware that not all Hindu communities in India treat Diwali as their biggest festival. For Keralites it is Onam and for Bengalis it’s Kali Pooja. Also for a lot of Indian ethnic communities, Indian New Year is in the spring, not the day after Diwali. We also need to recognize that in the diaspora, a lot of our practices are upper caste traditions. I have to share all of this because in the diaspora people celebrate their Indianness through the hegemonic North Indian culture’s definition of “Indian culture”. It is done with the assumption that this exported variety of North Indian Brahmin-centric Hindu Indian culture is the ONLY legitimate Indian culture. It often drowns out and even delegitimizes the cultures of people who don’t identify with this.

When we celebrate our culture in the diaspora, we have to critically think: Who gets to decide who Desi people are when Desi culture is so vast along the lines of language, religion, caste, region, migration and nation?

How do you see your artwork intersecting with your social justice activism?

I have to say that ever since I got into medical school it has been a struggle to find the safe spaces that I had access to so easily in undergrad. I think that isolation into just pure science/medical things actually inspired me to turn to art to be that space. I have always known that art is a powerful tool to explore some very complex issues, sometimes in ways that are more accessible than direct discourse. It occurred to me a couple of years ago that the characters I drew looked nothing like me. My heritage and culture were never seen in my artwork – that was such a lost opportunity. I was also fortunate to be in spaces where I got meet so many artists and creative people who were also into social justice activism. It made me want to do art that made a difference and was also very personal at the same time because there were so many other people who were enriching their communities because they decided to use their art in this sphere. Art and humanities classes were spaces in which I gained the language to describe my realities and other people’s realities. Gaining that language to describe your experiences is liberating. To have the tools in visual arts to express these experiences is even more liberating.

Who are some other artists that you admire that you’d recommend our readers check out?

There is the Iranian-American artist Negar Akhami who beautifully pays homage to Persian iconography in her paintings to address issues such as Orientalism, Western-centrism, Islamophobia and how these issues affect women.

A Sri Lankan artist based in Australia named Uma J is another artist who I love. Her illustrations are beautiful, minimalist and often inspired by great Hindu epics. I also like the South Indian/Tamil iconography in her work.

Naoka Takeuchi, the creator of Sailor Moon, is perhaps my first artistic influence. I remember learning how to draw from the beautiful colour illustrations she did for the Sailor Moon art books. I attribute her work for the anime influence in my artwork. Her art, in addition to being warm, detailed and vibrant, is really good at bringing her characters to life. If I were rich, I would buy these books.