#joe collins

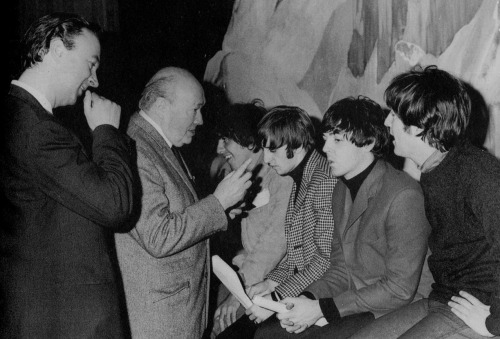

The Beatles during rehearsals for Another Beatles Christmas Show, December 1964. With them are producer Peter Yolland and promoter Joe Collins.

In 1986 Joe Collins published a memoir, A Touch of Collins. Below is a portion of the book where Collins recalls his memories of the Beatles and Brian Epstein:

Post link

The Beatles during rehearsals for Another Beatles Christmas Show, December 1964. With them are producer Peter Yolland and promoter Joe Collins.

In 1986 Joe Collins published a memoir, A Touch of Collins. Below is a portion of the book where Collins recalls his memories of the Beatles and Brian Epstein:

By the early ‘sixties rock 'n’ roll was a regular part of my business. The hit parades were as familiar to me as the multiplication tables, and I always kept an eye on the bottom end of the charts to see who was coming up and could be booked at a reasonable fee before he or she broke really big.

In February 1963 a promotions executive at The People telephoned me.

‘Can you find us an attraction for our summer ball? Something for young people?’

I recommended a new pop group from Liverpool called the Beatles, and said I’d try to book them.

When I tracked down the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, at his family’s furniture store in Liverpool, he was happy for his boys to perform at the newspaper ball. We agreed on a fee of £500.

Three months later, when the Beatles had their second No.1 hit, ‘From Me to You’, the man from The People phoned again. ‘This Beatles group you’re getting for us, I’m afraid they won’t be suitable after all for our ball. There’ll be such a rush for tickets we won’t be able to cope, and there could be trouble outside with their fans. Can you possibly manage to cancel our arrangement?’

When I told Brian Epstein of the cancellation, he did not disguise his relief. Since our earlier agreement the £500 fee I had negotiated had become ludicrously low payment for a Beatles cabaret.

However, this was not the end of my association with Brian Epstein and his Beatles.

Later that same year Stan Fishman, who booked live attractions for the Rank cinema circuit, came on to me. ‘Brian Epstein wants to do a Beatles Christmas show, but he has no idea how to go about a full stage production. Can you help him?’

I could, with pleasure! I booked the Beatles Christmas Show into the Astoria, Finsbury Park in North London for two weeks, commencing on Christmas Eve 1963.

I organized the scenery, hired some tabs (backdrop curtains), engaged a producer, Peter Yolland, and a compere, the Australian entertainer Rolf Harris. I reckoned that Harris, as a former schoolteacher, would be able to handle a rowdy teenage audience.

The other acts were provided by Brian Epstein. Apart from the bill-topping Beatles, there was a group from Bedfordshire, the Barron Knights, while the rest came from Brian’s stable of Liverpool talent, names he had launched that very year: Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas (who had already had three top hits), the Fourmost, Tommy Quickly and Cilla Black, Brian’s latest discovery.

Cilla, a toothy, 20-year-old redhead, had recently given up her regular job as a typist. In the 'sixties the rock audiences did not care much for girl singers, but it was customary to include just one female vocalist on a bill, if only to get some variety into the programme. For her act at Finsbury Park, I remember Cilla coming on stage in a pink mini-skirted dress to sing a lesser-known Lennon-McCartney song she had recorded, ‘Love of the Loved.’

When I looked at the printed programme for that Christmas show, I noted the credit I had been given: ‘Brian Epstein wishes to acknowledge with gratitude the invaluable assistance of Joe Collins in the presentation.’ I was actually co-producer.

As the show was intended to be ‘special’, not just a plain pop bill, Peter Yolland decided that the Beatles should perform a few sketches.

The night the show opened I wandered into the auditorium to witness George Harrison, dressed as a Victorian maiden, being tied to a railway line by John Lennon, in the role of Sir Jasper, the wicked landlord. Then Paul McCartney entered as the heroic signalman who rescues ‘her’.

The experience, appropriate to the plot, was like watching a silent film. The boys’ dialogue, if they were speaking lines at all, was drowned by the screeching audience. That was the first and only performance of the Beatles as stage actors.

That night at Finsbury Park, I met the Fab Four in person. I went backstage to introduce myself. ‘How’s the dressing room?’ I asked, sticking my head round the door of the shabby cell they were sharing.

‘All right,’ said drummer Ringo Starr, who always looked glum even when he was happy.

‘Is there anything you need?’ I asked politely.

‘Yes, there is!’ said Ringo promptly. ‘Can you find us some flex for our electric kettle? We want to brew up some tea.’

‘If you get us a lead for our kettle, we’ll give you some earplugs,’ George Harrison cajoled. ‘You’ll need 'em if you go out front!’ That I knew already.

Only one thing blighted our run at Finsbury Park. After the Beatles and other Liverpool groups had monopolized the top chart positions for nearly a year, a London group, the Dave Clark Five, suddenly became a threat. Their shattering, thumping ‘Glad All Over’ ousted the Beatles from No.1. The newspapers treated this item as a major sensation. ‘DAVE CLARK FIVE CRUSHES THE BEATLES!’ shrieked one of the headlines.

‘Well, we can’t be top 52 weeks of the year, can we?’ retorted Paul McCartney.

Still, despite those frantic, yelling girls in their Finsbury Park audience assuring the Beatles how much they were loved, Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr were green enough in show business to be upset about that gimmicky newspaper story.

On 14 January 1964, a few days after our show closed, the Beatles’ new record ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ became their first disc to reach No.1 in America, and by the end of the year they were as popular in the US as they were in Britain.

Young Cilla Black, too, the sole girl on the Finsbury Park bill, was proving too that she had a future.

During our Christmas-show partnership, Brian Epstein had invited me to dinner at his new London penthouse in William Mews, behind Harrods in Knightsbridge.

I noted, with some surprise, that Brian’s taste in furnishings was very arty. His choice of décor, with thick white carpeting and black leather settees, was not quite what I had expected from him after meeting his family from Liverpool, who were very down-to-earth despite their affluence.

Over our meal Brian talked about nothing else but his plans for Cilla Black.

‘She’s great… absolutely great,’ he kept assuring me.

While agreeing that Cilla had a warm personality, I could not agree with Brian that she was ‘great’.

He offered me evidence of her potential by playing a new recording of hers. I had already listened to enough music that day, but Brian was my host, so I put on an attentive expression as he switched on the record-player. The disc he played me was ‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’, a moving ballad by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. I realized Brian’s enthusiasm might possibly be justified. He was right: it reached No.1.

At the end of 1964, to round off the second amazing year of Beatlemania, Brian suggested we should jointly produce another Beatles Christmas show, to run from 24 December to 16 January 1965 at a very big cinema, the Odeon, Hammersmith, in West London.

We engaged two comperes, Jimmy Savile and Ray Fell, and the support bill, again all musical acts, included the Manchester group Freddie and the Dreamers, Sounds Incorporated, the Mike Cotton Sound, and a blues-oriented band, the Yardbirds, who had a particularly talented guitarist, a 20-year-old lad from Ripley, Surrey called Eric Clapton. The obligatory girl on the bill was a bluesy singer, Elkie Brooks, a baker’s daughter from Manchester. Elkie, like Cilla the previous year, was someone whose star potential Brian spotted early in her career.

The printed programme of what we actually called Another Beatles Christmas Show is now a souvenir I treasure, for it was illustrated with drawings by John Lennon, taken from the Christmas edition of his book In His Own Write.

The Beatles, after almost two years of adulation, were now getting worn down by the fervour surrounding them. They wanted a bit of peace, and visitors to their dressing room at Hammersmith rarely found a warm welcome.

One evening, when I was with them backstage, a Scandinavian representative from their record company EMI came in to be introduced to his bestselling product. He sat for a while in awe-stricken silence, watching them tune their guitars. Then he tried to start a conversation.

‘Tell me,’ he asked brightly, ‘what is the best thing about being a Beatle?’

John Lennon looked up at the man, his face registering no expression at all.

‘Best thing about being a Beatle?’ he repeated slowly. ‘Well, I guess it has to be that we meet EMI sales reps from all over the world.’

I cannot claim that I was one of the people to whom the Beatles wanted to chat, though as the show’s co-producer I would always make my routine call at their Odeon dressing-room.

‘How’s it going, boys?’

‘Fine, thank you,’ they would answer politely. That was the end of the dialogue. They’d simply stare at me for a moment or two, then continue talking to each other, usually about their music.

‘How do you get on with the boys?’ Brian Epstein asked me eagerly after one of my brief visits to the Beatles’ sanctum.

I laughed. ‘So far as I’m concerned they’re dumb… so dumb they’re making millions!’

Actually, from my point of view, the Beatles were a headache. I liked their records and even I, then a man of 62, was humming ‘She Loves You’. But I found it impossible to enjoy their stage performance. I couldn’t stand the way the audience screamed, making such an hysterical noise all the way through the show it was impossible to hear any of the music. The burly security guys worked as hard as any of the performers: they had to fight back at a rush of shrieking girls, apparently intent on storming the stage and tearing their idols to pieces.

Outside in the street before and after the show youngsters would be surging around the building hoping to waylay the Beatles as they left the theatre. The police trying to control these crowds were kicked, bitten and had their helmets knocked off in the frenzy.

Apart from the fact that my head was literally aching through the noise, I had a figurative headache, trying to spirit the Fab Four in and out of the theatre without anyone getting injured in the crush.

Like army officers planning a war operation, each day the theatre manager and I would meet with police representatives to devise some new Beatles escape campaign for the evening. We could never use the same method twice for the fans caught on too quickly.

However, at the end of that short Hammersmith Odeon season my head soon got right again, for I had been well rewarded. my personal fee for the two weeks’ work was £4,000, made up of my 20 per cent share of the profits and the sale of brochure programmes. In the 'sixties such earnings were a sizeable sum, especially as the Odeon profits were offset against a loss on another show I co-presented with Brian that season, Gerry’s Christmas Cracker, which played Scottish and provincial dates. I was surprised this show did not make a profit, for it starred the Liverpool group Gerry and the Pacemakers, Epstein discoveries who in 1963 had No. 1 hits with each of their first three records. (Gerry Marsden, happily, made a charts comeback in 1985 with a new recording of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’.)

The Rank Organisation was very pleased with my contributions to its coffers, and at the Rank circuit’s annual lunch following the 1964-5 Beatles season I was thanked officially by the company’s boss, John Davis, for having brought it the Finsbury Park and Hammersmith shows, the most successful stage attractions ever in the firm’s long history.

My association with the Beatles is a warm memory, not just because they provided a profitable venture, nor because they made a big personal impression on me: as I have said, I had no real communication with them. I was happy to have been involved because Brian Epstein was one of the most pleasant men with whom I ever did business. I found him charming, modest and completely straightforward in his dealings. I considered him a top-class businessman, and a gentleman.

Unlike some other managers and agents, he never regarded any of his artists as a mere commodity, to be signed up and hired out just to make money for himself. Brian was concerned personally for the welfare and future of each singer and musician he took on. In all my long career I have never met any manager so enthusiastic about his artistes. When we were together he talked of nothing else. He was thrilled that his boys were putting British pop music on the international map. It should not be forgotten that Brian, as a newcomer to show business, had tramped around the London record companies and music publishers literally pleading for a hearing for his Liverpool artists. He deserves much credit for turning British pop music into a high-earning export.

Post link