#lynette yiadom-boakye

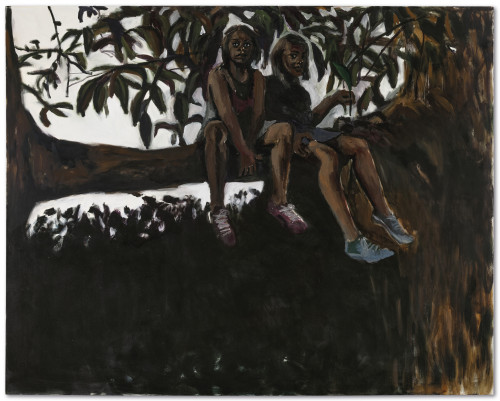

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (British, b. 1977), A Life to Die For, 2012. Oil on canvas, 200 x 250 cm.

Post link

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (British, b. 1977), A Life to Die For, 2012. Oil on canvas, 200 x 250 cm.

Post link

10pm Saturday

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

oil on canvas, 2012

Maurice Merleau-Ponty writes about painting as a practice that negotiates the material and the visual. For him, the body of the painter at work demonstrates the embodied nature of all viewership; the act transcends the simple transcription of reality by acknowledging that such a thing is in fact impossible—all seeing is contingent and situated, further mediated by its material representation. Painting lays bare these processes of negotiation, manifesting irresolution, compromise, and investigation on the canvas. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s gorgeous paintings push this line of thinking to its logical extreme, in that her portraits do not even pretend to depict objective reality in a subjective manner, which has arguably been one of the projects of figurative painting since the birth of the modern. Instead, she paints figures who are purely imagined. This centers painting as an act not of depiction but of creation; it acknowledges the inseparability of representation—and art as one of its primary vehicles—from reality. Rather than a description of material conditions of the world, then, I like to think that Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings literally create new worlds or new ways of being in this one, by giving them material form.

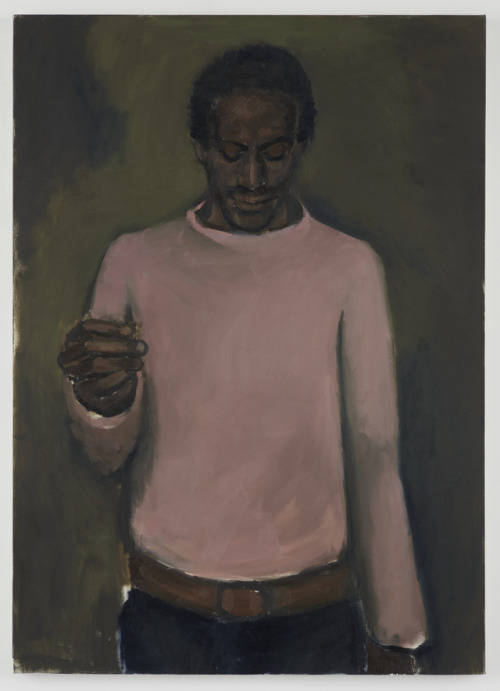

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Willow Strip, 2017

Post link

Thinking about Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits of imagined black men and women feels especially relevant today, the day after Philando Castile’s murderer was acquitted of his crime. The cop who killed him was found not guilty because of the narrative of danger and fear he projected onto Castile—a racialized expectation of violence that had nothing to do with Castile himself and everything to do with the color of his skin and how it coded him within his internalized white supremacy. Though obviously the stakes are much different, the same operation is at play in how Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings are interpreted by the white mainstream—as visions of black people and not just people, as insertions of blackness into a white lineage, as politically attached to external systems rather than inwardly focused worlds unto themselves. In her lovely review of the artist’s current show in New York, novelist Zadie Smith captured perfectly the haunting magic of her paintings and the violence done to them by such racializing interpretations. “Yiadom-Boakye has inherited a narrative compulsion, which has less to do with capturing the real than with provoking, in her audience, a desire to impose a story upon an image,” Smith writes. “Central to this novelistic practice is learning how to leave sufficient space, so as to give your audience room to elaborate. Yet the keenness to ascribe to black artists some generalized aim—such as the insertion of the black figure into the white canon—renders banal their struggles with a particular canvas, and with the unique problem each art work poses.”

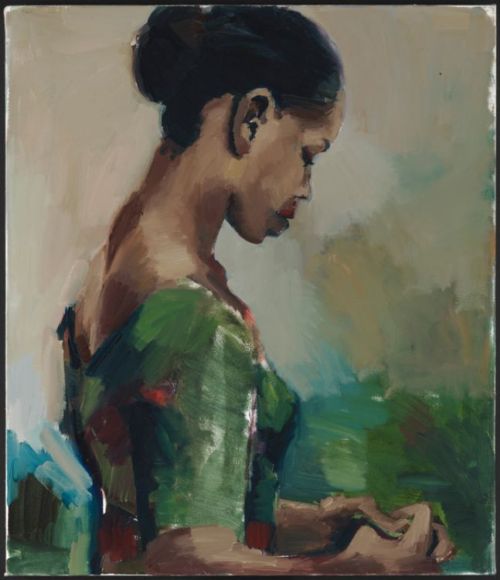

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Jewel, 2012

Post link

If Manet or Degas depicted contemporary subjects in baroque outfits, it might look something like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings. The exquisite painterliness of her portraits is virtually unmatched; the images fully reveal the process of their making and yet somehow transcend it. In fact, Yiadom-Boakye’s works are not portraits, but rather depictions of composite figures born completely from her own imagination. Her version of painting revels in its complete subjectivity, something she equates loosely with jazz. “The fantasies, nonsenses and random associations in my head meld with the life I live and the things that happen around me,” she has said. “It is necessarily flawed, histrionic, emotional, intuitive, illogical, personal, and largely lost when translated into words.” This helps understand her poetic titles, too, which suggest narrative threads not immediately connected to the paintings but no doubt enhance our pleasure in consuming them. This embrace of irresolution and emotion is precisely what makes her figures so compelling, so alive—perhaps suggesting she has accessed some truth unavailable to those who pursue “realistic” transcription. Like several of the artists I’ve written about so far, Yiadom-Boakye is subjected to a constant barrage of racializing interpretations, which cast her works as radically political for the simple fact of setting their black subjects in a more classical idiom. Take one step back and you realize the absurdity of such a proposition, its unchecked assumption of a white gaze, and how far the canon has yet to come.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Passion Like No Other, 2012

Post link