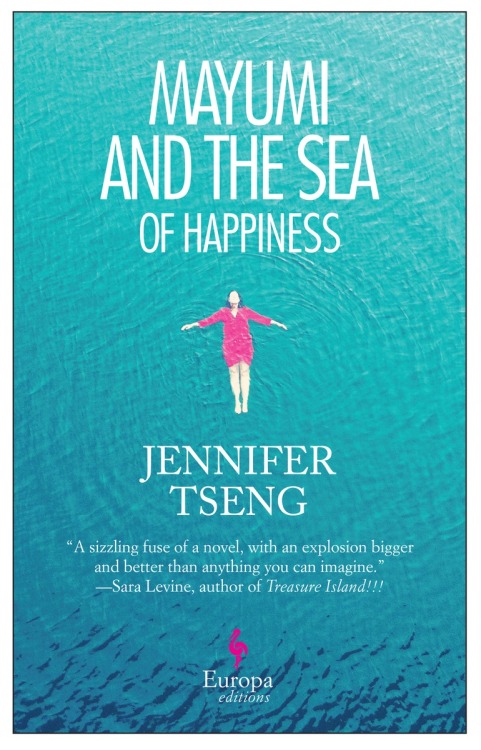

#mayumi and the sea of happiness

A WORD FROM THE AUTHOR

Jennifer Tseng, author of Mayumi and the Sea of Happiness

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Library by Jennifer Tseng

1. My most vivid memory of my childhood library is of a karate demonstration on the lawn. It was California. The sun was shining and the grass was thick and one of the karate-choppers was a woman. I had never seen a woman doing karate before! I wanted to take lessons. My father said no immediately, citing the possibility that I might kill my sister as the reason he could never allow it.

2. Our father was very concerned about our survival. His own, my mother’s, my sister’s, and mine. I was forbidden to get my driver’s license (too many accidents!). We were given swim lessons to prevent drowning in the event that the boat we might someday purchase capsized. We were given CPR training. We learned the Heimlich maneuver. We sewed our own clothing and backpacks. We grew fruits and vegetables and lifted weights as a family at the University gym. We were issued library cards.

3. As part of our survival training our father brought us to the library at the University where he taught. He would bring us to the “curriculum” section which was designed for adults learning to be teachers of young children but functioned perfectly as a children’s library for us. Once a week we would exit the many-storied library carrying stacks of books that went up to our chins.

4. Our father related to the library, as many immigrants do, as an infinite and necessary resource.

The library was where he borrowed materials for his citizenship exam, conducted research for his dissertation, found books on how to fix the plumbing, how to grow fruits and vegetables, books for our German American mother on how to speak Chinese and cook Chinese food. The library was a place he left his children in the care of women who were not their mother. And all of it was free. It was imperative that we learn how to survive without money.

5. At home my sister and I brought our library books into the bedroom closet or up into the tree and assembled our own makeshift libraries. We read to each other or to ourselves in silence. We had brought distant worlds home with us and wanted to enter them as quickly and completely as possible.

6. An unforgettable service that our town library offered (perhaps yours has this too) was something called “Dial-a-Story.” You could call the number and a recorded voice would read you a story. How endlessly we dialed that number! And how delighted we were when the story changed. I still remember the number: (805) 544-9899. Dial it, but don’t tell me if it’s out of service. In my mind, “Dial-a-Story” will always exist. It’s the perfect emblem of a library, an eternal place at the end of an invisible line, a place but also a person, a voice that tells stories, someone there waiting for you to lift the receiver and dial.

7. Like many children, my sister and I played library. We were especially enamored with the shapely, wood handled due date stamp we had seen the librarians use at the counter. We loved the sound of the book being stamped. The sound signaled the moment the book was about to be released to us, the moment the book would be marked as ours and we tried our best to replicate it at home.

8.During puberty my favorite library book was the illustrated Love and Sex and Growing Up (not popular topics in our household),a white cloth edition whose cover featured only the title in a large, all too legible pink font. It taught me everything. I checked it out repeatedly, blushing every time, but determined to have it again. To this day, the thought of handing it to the librarian still embarrasses me.

9. As a teenager in Boston, my husband was lucky enough to live in a place with world class libraries. He and his friends often wandered the streets up to no good. If it weren’t for the libraries, he said, they would have had no place to go.

10. As a student in California, there was a library he visited for its collection of records. He and his friends used the old records for sampling. He told me about a man in Brazil who has opened a public library devoted solely to records. The man has collected thousands and is still actively collecting. Many of the recordings - Thai funk or Ethiopian jazz or Filipino disco - would have been lost without his library; they are last copies of music that hasn’t been digitized, music that would otherwise never have been heard again.

11. My mother started a library at her church. There isn’t enough room for library shelves so she keeps much of the collection at her house and a portion of the books on a rolling cart whose selection rotates. She chooses the books carefully. Unlike the church, the books are nondenominational, though all of them have something to do with God or spirituality or social change. In a conservative Catholic parish in a town of 5,000 the books are considered by some to be dangerous. Her little cart is quite controversial.

12. My own job working at a library changed when I began writing a novel set there. Before that my writing life had been solitary. Writing MAYUMI was a strangely collective, exhilarating experience. Going to work became a thrill. Daily I asked the librarians questions: How do people meet people on this island? If two people were going to have a secret affair where would they rendez-vous? If the main character were to sleep with a 17-year-old, would you hold it against her? Their answers changed the course of the book.

13. Mayumi on libraries: “Then again, had the young man and I met on a train, I might have wished we had met in a library (One is doubly afloat in an island library, surrounded by water, surrounded by books.), in a sanctuary that never arrives late or suddenly, one that never departs slowly, only to disappear out of sight. In its intimacy and safety, a library is the opposite of a train. It is that which remains, that which holds people (children are the exception here) while they are, for the most part, not in motion, that which holds people while they dream, while they resist travel even as they read of other worlds.”

Post link