#monthlymotifgxo

“And you’ve only ever read stories about people like you, right? You’ve never met one of your

kind before now. Well, except for Beatriz,” she added. “Ain’t that so?”

“Yeah,” Esther answered reluctantly. She sensed a trap coming, but she couldn’t figure out how to step around it.

“All those stories you’ve read,” Amity said softly, pulling her hat back off her eyes by a few degrees. “Who gave ’em to you?”

“The Librarians,” Esther said.

“And who gave ’em to the Librarians?”

Esther thought hard about that one. The things the Librarians brought weren’t subject to the Textbook Approval and Research Council, since they only worked on schoolbooks, and they weren’t subject to the Media Review Committee, since they mostly did film and television. “The Board of Materials Approval?” she guessed.

Amity nodded. “And what do you think that Board wants you to believe about yourself?” She paused, but it wasn’t the kind of pause that wants an answer. “You might not have a happy ending coming to you, Hopalong. But if you come to a bad end, it won’t be on account of what kind of person you fall for. I’ve seen a lot more of the world than you have, and I can tell you upright: I’ve seen as many good ends as bad ones for your kind of heart.”

Upright Women Wanted by Sarah Gailey starts off a yarn about a dystopian fascist United States where resources and tech are so consumed by war effort and maintaining hegemony the country’s living standards have reverted to looking like something out of the Old West. In one dusty corner of Arizona, Esther Augustus has run away from a fiancé and the death by hanging of her best friend and more Beatriz at the hand of Esther’s father no less. Stowing herself away with the Librarians, who travel from town to town caring for and dissemination the proper books and other state approved materials, it’s a group of the upright sort of women Esther thinks she needs. And she’s right, about one thing. She’s found her kind of people.

Generally, I like queer westerns, be those takes on the past or speculative futures. Transgressive librarians likewise are golden. Though, Upright Women Wanted if I might use a quaint phrase, as this novella has a seemingly endless supply of them, feels rather like a lick and a promise.

Readers are left flat in the middle of personal and national events. As the latter is given next to no exposition (so many questions), character driven this tale is. Two of the Librarians Leda (from an organized crime family in the Northwest) and Bet (from the military Central Corridor), truth be told in a long-term relationship, by all outside appearances don’t come off seemingly as anything more than Librarians who ride together. Plus turns out a good quality Librarian has parcels that include smuggled materials and people as part of the resistance. Though when it comes to the goods on a guilt-stricken Esther, her dad’s powerful as a Superintendent, the fiancé Silas is little more than a name, Beatriz a memory barely cold in the ground and there’s more life-threatening situations and death to be dealt. Yet, the immediate focusing subject is Esther’s attraction to an Apprentice Librarian Cye (from the manufacturing Northeast that uses child labor). Cye tasked with acclimating Esther on the road has a direct personality, as they also make it clear to Esther:

“I’m they on the road and she in town. You can take time getting used to they on the road, but if you forget about she when we’re in town, you’ll have to learn how to think around a bullet.”

People cope with issues and trauma differently but, Esther’s attraction to Cye coming up at once and permeating even as chatter in certain situations had me so off kilter reading. I further double checked this title’s categories to make sure I hadn’t missed romance mentioned. Not that expecting such a strong element may help much what with the way the pacing is more a stampede.

Of course, there is a connection between death and desire in the text. Esther, the pansexual protagonist, is convinced by all the stories, education, deeds, and principals she knows that there’s only one sort of end for anybody who is somebody different. Breaking out, finding real refuge, yourself and community, those steps towards making a genuine life, and resistance even under long shadows is where the heart of this story really rests. Such is where I bet readers can feel and love this little book and its mere existence (weaknesses though it may have) too.

Upright Women Wanted by Sarah Gailey is available in print and digital (including audio) from Tor Books

Our bodies wailed and writhed, we itched with restlessness. We walked around like large irate animals in our parents’ houses, shouting for something that could still the strange swells, but wherever we looked all we saw were ready-made Female Models. We shut our mouths and closed our eyes, refusing to accept the inevitable. It was instinctive, an ember in the chest: anything could happen to us— just not that. So we fled to the greenhouse, turned away from the world, sough comfort in the earth and the flowers and the insects.

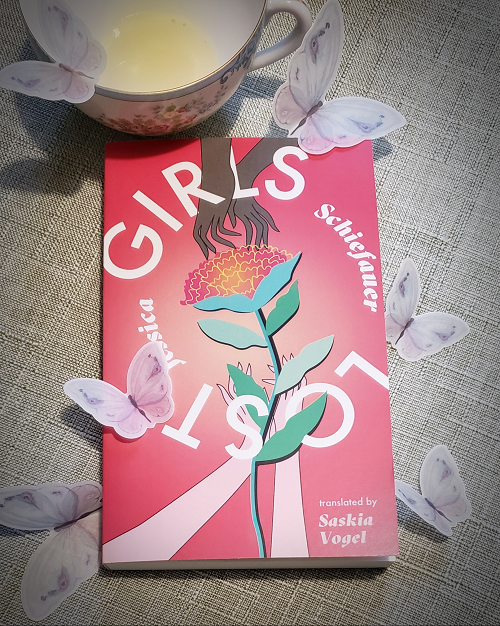

Kim, Momo, and Bella are at the hellish age of fourteen, longtime best friends and increasingly harassed and bullied at school. They still have a sanctuary though in the greenhouse at Bella’s. One day planting a strange seed that grows an unusual orchid like flower with sweet smelling nectar, they discover its power to physically turn their bodies into boys for a night. Embarking on a game that will not only test their friendship but, for one of them is much more serious.

Garnering prestigious awards and nominations, both banned and taught in schools along with glowingly recommended in LGBTQ+ lists, this was one of those dark YA fairytale-like books in a magical realism vein that I very much wondered what the author has to say about it. Fortunately, a Publishing Perspectives interview with Jessica Schiefauer from 2014 gives context. As the perspective of the English translator Saskia Vogel.

In the simplest terms in an earlier interview with TT News Agency in 2011 Schiefauer also puts it “This book doesn’t investigate what it is to be a boy,it investigates what it is not to want to be a girl.”And “I wish we didn’t have to be so strongly defined by our genders. I think that is the key for Kim, to just be Kim and not have to choose.”

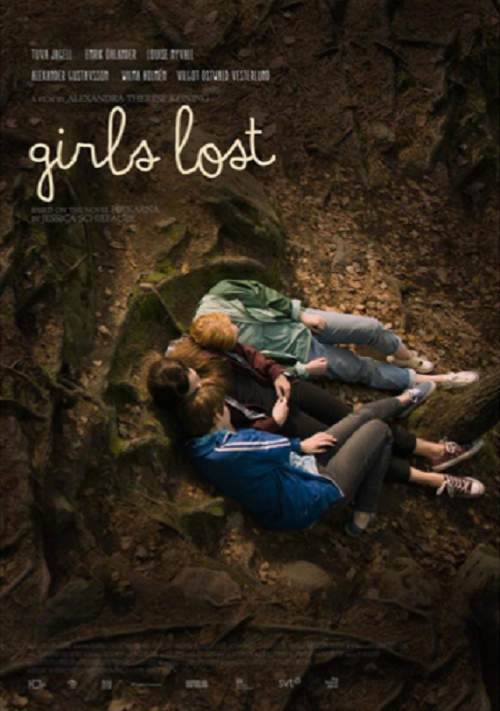

Similarly, the Swedish title of Schiefauer’s novel is worth noting in that Pojkarnatranslates to ‘The Boys’. Several other translated editions echo this but there is sometimes variation with a different title such as Girls.Yet this went further when the film adaptation was screened internationally in 2015 using ‘Girls Lost’ in English. Though excerpts of the novel translated by Saskia Vogel first appeared in Words Without Border in 2014 using ‘The Boy’s’, the full novel’s English edition that followed years later in 2020 ties itself in name to the film. While further setting itself apart rejecting the largely subdued palates of many other editions by sporting a screaming pink neon cover by Anna Zylicz with illustration of hands holding and reaching for a flower, white text wrapping in a circle.

But if we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, what is it about the material inside that has proved so intriguing? As mentioned in this case the novel has not just appeared in many languages but alongside a live-action adaptation. And the film’s interpretation is additionally interesting in that it led to the source material being analyzed more as a trans or queer narrative. (That categorization or not as the author says is something she’d wish take a back seat to discussions of gaze . To this broader point, I’d say the way people are perceived and therefore treated and conditioned, everything for that matter, can be immensely messed up.)

The director Alexandra-Therese Keining in only her second film and with a novice cast doesshift and give more space to certain issues of both femininity and masculinity, gender identity and performativity, along with sexuality. (Though the book is more explicit in some respects, enough it was as I mentioned banned in some schools in Sweden). This has a particular effect on the characterizations and relationships and the complexity.

Tony a troubled punk on the exterior is an opportunity to show how (toxic) masculinity can also be restrictive and damaging. (Here too is where I’d like to point out that boys do still face messages about their bodies and value along with social expectations as well.) During Kim’s nighttime excursions they form a connection, that is not without sexual tension. Unfortunately the powerful bad boy mold can be flawed or an ill fit, and while overdue emotions and vulnerability surface, volatility reveals itself too.

Momo and Kim as in the book share complex feelings of more than friends. As the story progresses Momo is acutely scared for and desperately tries to hold onto Kim. Kim confides more in Momo and a scene between her and Kim that markedly sticks out in the book is changed for the film.

Bella who quickly tires of the nighttime outings is another example of “ways of contending with the term “gender”.” Misogyny is the topic that exists at the forefront of the novel. Bella is the target for Schiefauer’s recreation of an assault she witnessed in her youth. This is too a coming-of-age story and Bella as well reflects traditions of nature and the (divine) feminine. The metaphors with the greenhouse, and the special flower she chiefly looks after along with the friction that develops between her and Kim, is unsettling. As events also involving Momo near the end. No one despite their form can be free from violence or trauma. Though the book carries on to a different end point than the film and both are very open to interpretation.

Between its mediums I honestly prefer the film as Keining,who has become known for work with LGBTQ+ themes, takes up a center focus on certain subjects in contrast to the book. Yet, it can be argued as still continuing a binary and essentialist atmosphere. The book relies on a dichotomy that can undermine the nuance that does exist. I think it can be very challenging to craft a story like this with a lens thru identity, gender, and fluidity focused on the circumstances of young people growing up that won’t give some misgivings about what is trying to be said. Each individual navigating identity, sexuality, gender and growing older are experiences that remain regardless. Girls Lost seems to endure in the consciousness and it raises questions because of this. Yet for a story utilizing gender transformation to say something about identity and perception, it feels strangely somehow less world shattering going about it.

Girls Lost by Jessica Schiefauer is available in English translated by Saskia Vogel, in print and digital from Deep Vellum

View a trailer for the film adaptation directed by Alexandra-Therese Keining

Syzygy? Androgyny? I’m no man and I’m no woman. Who needs gender anyway? I just want to get out of this place, to be on my own.

I’ve got no desire to see the collapse of humankind or the end of the world. I just want everyone to enjoy their lives. That’s why I came here — to a different time stream, a different planet, a different universe.

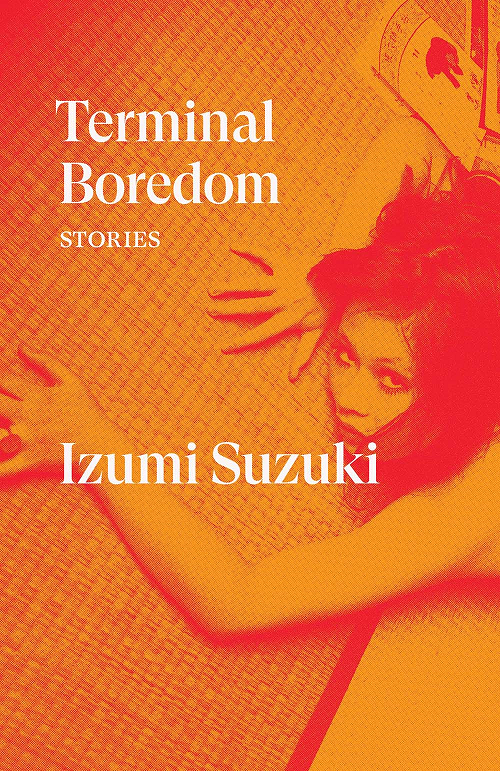

A book setting SFF community abuzz in April 2021 was Terminal Boredom, an English translation of seven, decades old, very dark speculative fiction short stories by Suzuki Izumi. Imaginings that are nostalgic, melancholy and sometimes queer offer readers peeks an extreme matriarchal society, overpopulation and cryosleep, scattershot appropriation of pop culture and humanity’s influence through at the edge of the universe, limitations of the virtual world, transformation and times effects, a pair of lovers caught in fears of an interplanetary war, and in the title story ennui of youth and dangerous numbness in a media saturated world. Told with psychological emphasis writing that can carry forward to today, some of the overreaching themes touch on gender or are about (dis)connection between people or the past.

Suzuki too an actress and model I want to say the picture used on the cover is one of her nude, dated to the early 70s and found (possibly among other places) in a photo book “Izumi, this bad girl” with photography by Araki Nobuyoshi (who is a whole other matter). Described as an incandescent creative by some, it’s a notable development for examples of her work to be translated to English so many years after her untimely death in 1986 due to suicide. Though, readers in this book won’t find an introduction or afterword to provide such details about her life or, context to her writings. An odd choice when Suzuki has been all but unknown in Anglophone circles, and even in Japan often filtered through lenses of other figures around her. Six different translators were also tasked to bring this collection of stories, chosen from a larger Japanese volume to English. If one finds appeal, know Verso also has plans for another.

Terminal Boredom by Suzuki Izumi is available in English translated by Polly Barton, Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, Aiko Masubuchi and Helen O'Horan, in print and digital (including audio) from Verso Fiction

Amid a lot of difficulties my new year’s resolution for 2022 is to stick to what’s on my shelves. I did well last year in trimming down my TBR into something manageable. So, the Beat the Backlist challenge remains a good fit.

And since I like to try something new too, this year adding the simple Monthly Motif Reading Challenge by Girlxoxo. (They also have a keyword and book award challenge.)

Wishing everyone great reads across the year!