#osteoarchaeology

Richard III : The twisted bones that reveal a king

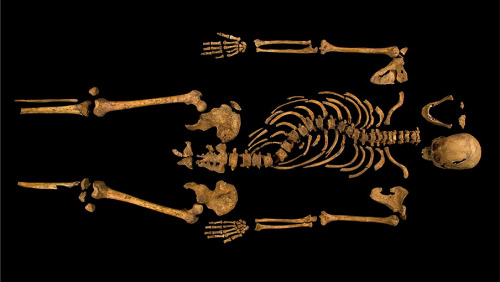

- When Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, he was said to have been buried in Greyfriars church, Leicester. But this church was lost until archaeologists excavated a car park and discovered medieval remains. Victorian foundations had almost destroyed the entire grave and the feet were lost, but the bones still promised to provide a treasure trove of information - would they also reveal a king?

- Richard III was portrayed by Shakespeare as having a hunched back and the skeleton has a striking curvature to its spine. This was caused by scoliosis, a condition which experts say in this case developed in adolescence. Rather than giving him a stoop, it would have made one shoulder higher than the other. Highlighted are the facing sides of the 10th and 11th thoracic vertebrae, showing uneven growth as the spine bent.

- Evidence of a number of wounds were found on the skeleton but the face area was largely unmarked, apart from a sliced cheekbone. The skull has undergone a CT scan and the results will be used to reconstruct the king’s appearance. No portraits made during his lifetime have survived and some later copies show signs of having been altered to make him appear more sinister.

- The back of the skull shows dramatic injuries. One consists of a hole near the spine, where a large piece of bone has been sliced away by a heavy bladed weapon such as a halberd. This, along with a smaller wound opposite, may well have been a fatal injury. A smaller dent which cracked the inside of the skull, is thought to have been caused by a dagger. There are a further five wounds on the skull, all inflicted around the time of death.

- The teeth of the skeleton have provided important information. As well as evidence of disease and tooth decay, calcified plaque can be analysed for evidence of diet and environment. He had lost several of his back teeth before he died, probably due to dental caries. DNA samples were extracted from the teeth and the right femur to compare with known descendants of Richard’s family. Despite the potential for DNA to degrade, a match was found.

The back of the skull shows dramatic injuries. One consists of a hole near the spine, where a large piece of bone has been sliced away by a heavy bladed weapon such as a halberd. This, along with a smaller wound opposite, may well have been a fatal injury. A smaller dent which cracked the inside of the skull, is thought to have been caused by a dagger. There are a further five wounds on the skull, all inflicted around the time of death.

Interactive feature produced by Greig Watson, Christine Jeavans, Mick Ruddy, Sophia Domfeh and Paul Kerley.

Photographs by University of Leicester and Jeff Overs. Portrait of Richard III: Collection of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Cannot contain excitement, behold the awesome power of Anthropology, or more specifically Archaeology/Osteoarchaeology!

Post link

How Forensic Techniques Aid Archaeology

- by Diana Valk

“In 2012, archaeologists discovered the skeletal remains of an adult male buried under a car park in Leicester, England. Using DNA evidence, they were able to confirm the identity of the skeleton as that of Richard III, the former king of England who died a brutal death in the Battle of Bosworth. On March 22 of this year, thousands of people lined the streets of Leicester to watch a horse drawn hearse carry the coffin containing Richard III’s remains to Leicester Cathedral. This solemn moment was made possible by intrepid archaeologists using forensic techniques. Scientific methods such as the DNA testing used to confirm Richard III’s identity are closely associated with forensic science, but they are just as useful for archaeologists as they are for criminologists.

Similar to crime scene investigators, archaeologists aim to gather as much evidence as possible in order to interpret how our ancestors lived. Unfortunately, archaeological sites provide incomplete and even misleading pictures of the past, leaving archaeologists to tease apart the evidence and formulate likely scenarios. Sometimes it is difficult to know if the interpretations made are correct or way off target. Forensic techniques such as fingerprint matching, DNA testing, and chemical residue analysis help dispel some of this uncertainty by providing concrete evidence to support or refute hypotheses.

Fingerprint Analysis

As one of the oldest forensic techniques for identification, fingerprint analysis has intrigued archaeologists for many years. In archaeology, fingerprint studies are focused on ceramics, because as a potter creates a vessel, his or her prints can mark the clay. Once the clay is fired, the prints are preserved.

As early as the 1930s, archaeologists were using fingerprint analysis to help determine site timelines. It was at the Tell en-Nasbeh site in Palestine that Dr. William F. Bade used fingerprints to help him understand the confusing artifact deposits at the site. He was able to conclude that one potter had molded many of the vessels and therefore any layers that contained this potter’s work belonged to the same time period” (read more).

(Source:JSTOR Daily)

Post link