#souzou forest

So Japanese is in the habit of not actually telling you who’s doing what actions.

たべます。 “Eat.” = (I) eat/ (you) eat/ (he) eats/ (she) eats/ (they) eat/ (we) eat/ etc.

This is called an implied subject, and we do it a little bit in English too.

“Clean your room.” = (You) clean your room.

“What did you do today?” “Went to school.” = (I) went to school.

But in Japanese, it’s sort of the default. You often don’t say who did something unless it’s not clear or you want to emphasize it. Everyone just kind of figures it out from context. This is a challenge for students of Japanese before they get used to it, but it’s normally fine for native speakers. The most heartwarming part of the song Souzou Forest, however, actually kind of depends on a native speaker misunderstanding an implied subject. Let’s watch!

(warning: there’s a freaking doctoral dissertation about Souzou Forest under there. Proceed with caution)

[If you haven’t heard of this song before, it’s part of the Kagerou Project, a series of Vocaloid songs which all come together to make a surprisingly complicated story. The song started out being called Souzou Forest (想像フォレスト or “Imagination Forest”) and was renamed Kuusou Forest (空想フォレスト or “Fantasy Forest”); you will see people use both titles. It comes with a music video; go here for the original video from the creator’s Nico Nico account or here for a fan’s cover on Youtube with English subtitles.]

First, some quick rules of thumb for dealing with implied subjects:

- Use your common sense. If Bob saw a bird earlier and you’re seeing the words “flew away” now, it’s probably the bird unless Bob is getting super metaphorical about something.

- Look for the “main character” of the sentence/paragraph. If we’re talking about how Bob’s day went, Bob is probably going to be the subject of most of the sentences in our story. If a new person just appeared a few words ago, we’re probably talking about what that person did next.

- If there’s absolutely zero context, they’re probably talking about themselves (if the sentence is a normal statement) or you/the listener (if it’s a command or a question).

On to the song. Souzou/Kuusou Forest is about a girl (Mary) whose grandmother was basically Medusa. She lives in a house in the forest all alone, partly because she’s worried about turning people to stone with her crazy gorgon eyes and partly because every time she’s seen people they’ve been afraid of/violent towards her.

(Note that she gets through her entire life story with only three uses of the word “I/me/my” 私(わたし). For comparison, in the subtitled version in the link up there she uses I,meandmyroughly 20 times by my count. Japanese loves implying things.)

One day a boy (Seto) shows up at her door and she flips out and hides in a corner. She tries to warn him of the danger:

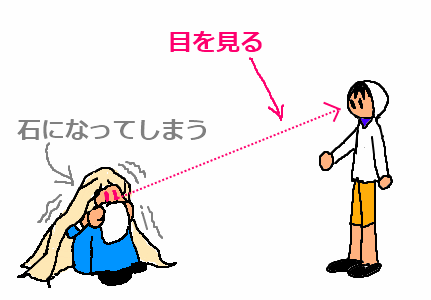

目を見ると石になってしまう。

- 目(め)eye/eyes; を (object marker); 見る to look; と if; 石(いし) stone; ~になる turn into~; ~てしまう do ~, and ~ is bad.

- “(sentence 1)と、(sentence 2)” means that if sentence 1 happens, sentence 2 will happen naturally/automatically, or that sentence 2 happened all on its own when I did sentence 1.

- (verb)てしまう can mean that (verb) is irreversible, or that it would be sad if (verb) happened, or both.

“If (you) look at (my) eyes, (you’ll) turn to stone!”

…or at least that’s what Mary intends to say. But all this sentence actually tells you is that when someone looks at some eyes somewhere, something turns to stone. The subjects of “looks at eyes” and “turns to stone” are implied.

Let’s see. “Looks at eyes.” There are only two pairs of eyes in the room (Mary’s and Seto’s), so no matter how you interpret it they’re looking at each other. No worries there. But what about the subject of “turns to stone?" Mary (and the audience, which knows her backstory) thinks it’s pretty obvious that Seto would be the subject of both "look at eyes” and “turn to stone.” You’ve got a Gorgon and a regular dude in a room together, what else could be going on in that sentence? Context wins the day.

Seto, on the other hand, has not been blessed with the sort of context that we all take for granted these days. He may not even know that Gorgons are a thing that exists in actual reality, let alone that he’s talking to one. All he knows is that he found a random hermit house in the woods and the girl inside freaked out when she saw him and is now cowering in a corner covering her face. Based on the fact that people are usually talking about themselves, plus the fact that Mary, frozen in fear, is the most stone-like thing in the room, Seto concludes that Mary must have some kind of crippling social anxiety.

“If (I) look at (people’s) eyes (I) turn to stone” –Seto’s interpretation

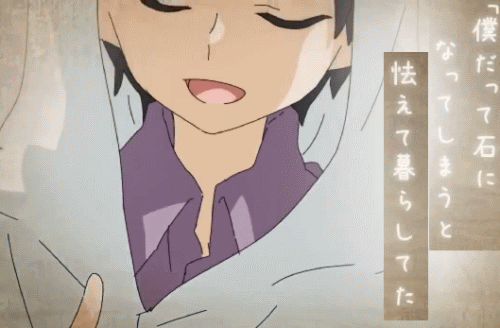

Seto knows that feel, so he decides to comfort Mary (lines photoshopped into single pictures for space concerns):

僕だって石になってしまうと怯えて暮らしてた。

- 僕(ぼく) I; だって also, even (as in “even I do that”); 石(いし)になってしまう turn to stone; と quotation marker; 怯える(おびえる) be afraid; 暮らす(くらす) live; ~てた was doing

- This と is different from the "if” と above. It marks a quote. Here, he’s quoting his own thoughts, the ones that made him afraid.

- ~てた is a contraction of ~ていた (was doing~ habitually in the past).

“I used to live my life afraid of turning to stone too.”

でも世界はさ、案外怯えなくて良いんだよ?

- でも but; 世界(せかい) world; は (topic marker); さ (emphasis, especially for an explanation); 案外(あんがい) surprisingly, unexpectedly; 怯える(おびえる) be afraid; ~なくて良い(なくていい) it’s okay/fine if you don’t~; んだ (emphasizes an explanation); よ (even more emphasis)

“But I’ve found that the world isn’t as scary as you’d think, you know?” (literally “But the world is surprisingly okay to not be afraid of EMPHASIS EMPHASIS EMPHASIS”)

D'awww. Seto’s so sweet.

And so lucky that Mary’s eyes aren’t as potent as Grandma’s. Context saves lives, man.