#surrealism

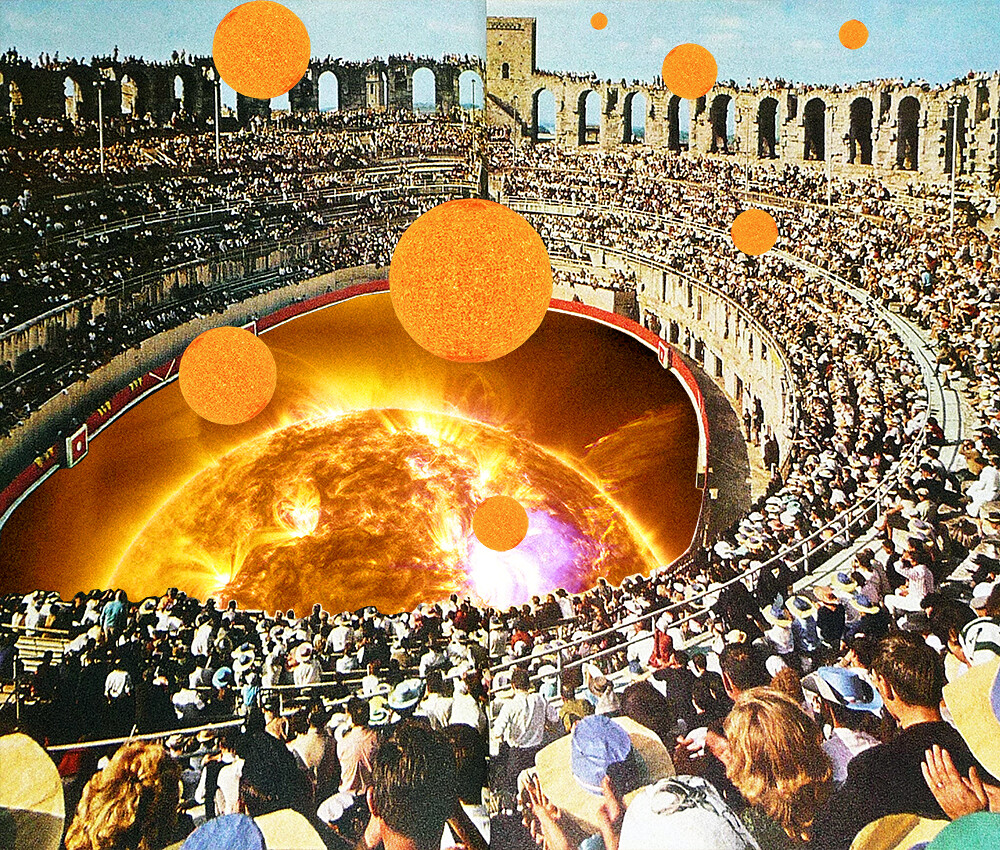

Planetary dream por Mariano Peccinetti

Por Flickr:

www.facebook.com/CollagealInfinito www.society6.com/Trasvorder www.instagram.com/marianopeccinetti

Equilibrium with stars por Mariano Peccinetti

Por Flickr:

www.facebook.com/CollagealInfinito www.society6.com/Trasvorderwww.instagram.com/marianopeccinetti

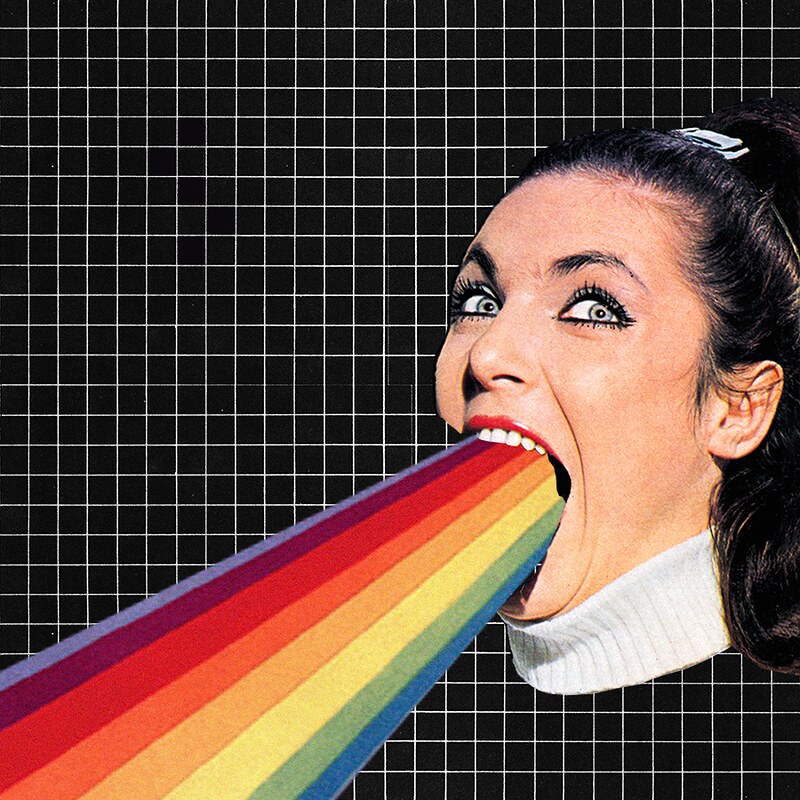

Rainbow, mountain, sounds por Mariano Peccinetti

Por Flickr:

www.facebook.com/CollagealInfinitowww.society6.com/Trasvorderwww.instagram.com/marianopeccinetti

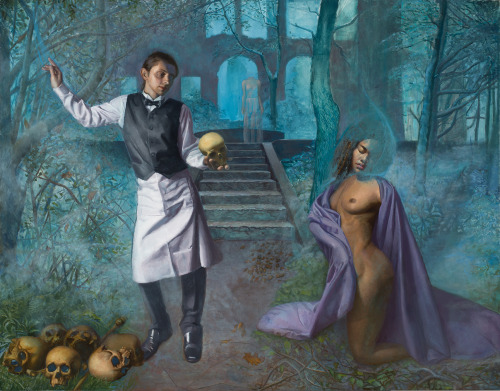

West hallucinations por Mariano Peccinetti

Por Flickr:

www.facebook.com/CollagealInfinitowww.society6.com/Trasvorderwww.instagram.com/marianopeccinetti

“You were up there, weren’t you?” He asked.

“No. I was not,” I replied.

He looked me up and down and with a quiet grimace, continued, “I told you never to go near that house. You understand me, boy? You tell me you understand.”

“But I wasn’t,” I lied.

“I can see it. I know you did because I can see it in your eyes. I can still see that fucking house glowing in your eyes—glowing white,” he sneered. “You tell me, boy—you tell me you won’t evergo near that house again.”

We all knew about the house. We walked by it every afternoon on the way home from school. There were leaves, vines and shrubs that had overthrown the façade of the house. The vines and weeds had strangled the wooden frame of the front porch. Leaves had settled over the path that led up to it from the street, like pale-brown blankets of snow that were cruel and fragile like fragments of skulls. The old, frosted window panes hid what was inside. The broken windows on the second floor felt like gaping maws trying to swallow us into its darkness. Even on the sunniest summer days, no light seemed to make it inside those windows. Just beyond the window-frame, you could see the faintest hint of that old, sagging custard-colored wallpaper with its playful little ship’s anchor-pattern across it. But beyond that—darkness.

We’d been told that the house had been empty for years, too—empty since before any of us had been born. But it never felt empty to any of us. I we knew that when our parents had told us it was empty, that they did not believe this, either.

That was why we shuddered every time we walked past it. There was not a single time that we ever saw the house which we didn’t swear we’d heard it calling soft and innocent from the earth. And we did. Every single one of us heard it bellow our names.

Trevor heard it whisper ‘Trev, don’t go.’ Garrett heard its broken voice slide out from the cracked basement window and call out, like a crone siren, ‘Garrett, please.’

And I had heard it call my name, too. Every single time. ‘Laney… Laaaannneeeyyy.’

We were all told never to go into the yard. And heaven help our hides if our parents ever found out that we’d gone any closer to the house than the sidewalk. Nobody in the town trusted the house. But nobody was willing to do anything about it, either. Everybody claimed it was ‘cursed,’ but nobody knew that. There were a few skeptics who believed it was nothing more than superstition and childish myth. But the skeptics never did say this with a weak shake in their voice. They’d stood outside the house, looked up on that hill and refused to go into the yard.

Still, everybody told us the house was empty. Had been for years. That he must’ve died some time ago, because, when theyhad been children he was old and ragged.

And everybody told us that the boy had drowned in the river or been eaten by the wolves in the woods or simply run away from his carless parents.

But then, where did he go? Why had nobody ever found him?

Why did we hear him crying from the basement, begging one of us to come save him? Begging us and chilling our spines because we would have put our lives on it that we were hearing him calling to us.

We would tell our parents and sometimes, they would even stand outside and listen. And when he would call, they would turn away and insist they heard nothing. They would hide their fear from shame.

But we knew better.

My father was not a stupid man. But I, like every child, thought I could fool him—thought I could sneak around his law. And on a dare, I’d stepped into the yard. I lowered the toe of my sneaker into the yard, shaking in my bones as if it were a lake and a crocodile had been primed to leap out and devour me.

But the house would never be so merciful to kill quick like a crocodile. It would stalk you and watch you like a snake or a crow, waiting and patient enough to wait however long it takes. It would echo in your mind until your thoughts turned rotten like the apple tree in its front yard, where the birds and squirrels and even foxes refused to venture near its easy fruits.

And my father knew. He’d seen the house in my eyes, like a daguerreotype of the structure etched into my cold irises. He’d seen it and he knew. He knew about the sailor who’d lived there when he was a child. He remembered when the police came out and questioned the old man. And he remembered when, not long after, the police went missing- just like the boy had.

He remembered when people started to put their nose down and try to ignore it—ignore the fact that the old man was still there and was watching them from his porch and grinning with decaying teeth that he’d sharpened with old, broken seashells until they were long and pointy like shark’s teeth.

“That boy did it to himself—shouldn’t steal from old men like that,” they would say to one another as they walked by the house, as if hoping the old sailor would overhear them and spare theirchildren.

And a few more disappeared. Some right out of their bedrooms without a scream or cry. No bodies. No witnesses. No nothing, really. But soon enough they would start to call from that house. They would take their turns crying and begging from the basement window.

I had never seen my father scared, before. He’d fought in the war, and I still had never seen him scared. Only when he warned me about that house, did he seem petrified—like he knew he had no control over this world and he was just a glass bottle floating in an ocean of darkness. War had not put this in his mind, but that house and that old sailor had. Those shark teeth had.

He’d been a child and he’d seen with his own eyes the old sailor watch him and smile at him with those jagged, disgusting teeth–smile at him like a beast growing hungry and reveling in its swelling appetite because it knew when it finally diddevour, it would be all the more satisfying. The old man had stayed in the long shadows of the porch, so that even in the brightest afternoon day, nobody could see anything but his crooked clown smile and his eyes—eyes that everybody will tell you glowed like beads of pale fire in the darkness.

“He’s in my mind. He’s in my fuckingmind and those eyes are always glowing,” I had heard my father say to my mother once, weeping and trembling in his throat.

He’d seen the pig corpses hanging from the apple tree branches. He’d seen the plumes of smoke that crawled into the sky from the cellar doors, sifting through the cracked wood like the bony arms of creatures reaching aimless and desperate for the light just outside. And he’d seen the mason jars that were filled with bloodied teeth, sitting inside one of the windows. He’d heard the crunching bones, the machine screams and whirring blades echo up and out of it.

He knew I’d been to the house because he saw in my eyes the same thing he saw in his own every time he looked in the mirror.

And the next time I walked by the house I saw the rotten apples on the dead leaves. I saw the scraggly mess skeletal bushes and twigs that climb up along the side of the house, reaching up to the second story where the paint had completely stripped from the siding and left the bloated, warped pieces of wood peeling from the house’s frame. I saw under the grey clouds, the upstairs window cracked open and I heard him calling to me through it—begging me to help him.

“There’s no way,” I whispered to myself. “It’s been too long.”

I saw the ivy that draped over the porch—forest green and lush like it had a pact with the death that haunted the place—like it could flourish on the corpse of a house, so long as it grew into a trap to help lure us inside and tangle us in a slick web of green glossy leaves and stems.

I heard him calling me over and over. “Laney… be a good girl… come and get me. Laney…” And I know—I just know—on that final call, he was watching me through that blanket of ivy. I swear to this day that I saw those pale fire eyes.

“There’s no way,” I whispered to myself one more time. “It’s been too long,” I said.

I stuck my hands in my pockets and started down the sidewalk.

A sky blue house

against lemon yellow sand.

Horizon stretched for miles,

walls that lock me in.

This thought isn’t my own,

memories twisted in a cage

begging me, ‘please stay,’

saying, 'ignore the stagnant waves.’

An azure ocean

frozen like a winter’s lake.

Waves that sing a song,

but never rise and never fall.

This thought isn’t my own,

my mind sharpened in a cage,

begging me, 'please stay,’

saying, 'ignore the timeless day.’

A sky blue house

a white but knobless door.

A dream that stretched for miles,

a dream that locks me in.

This home isn’t my own,

an illusion bearing teeth

begging me, “please leap,”

saying, “find what lies beneath.”

A jagged cliff

against loud, booming waves.

Fear stretched for lifetimes,

a door that opens wide.

This world isn’t my own,

a sapphire shifts below

begging me, “please come,”

saying, “back to the blue home.

Plate XXXII [c. 1750]

‘…as at A, B and C. in Plate XXXII. which represents their Sections, if all may be a proper Term for an infinite or indefinite Number, we may justly imagine to be the Object of that incomprehensible Being, which alone and in himself comprehends and constitutes supreme Perfection.’

Illustrator: Unknown

Published:An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe(1750)

Author: Thomas Wright

Post link

In its newest exhibition, Booth Gallery gathers the work of eleven modern visual artists experimenting with the style and themes of the Surrealists.

Disturbing Works of Modern Surrealism

Post link

![Plate XXXII [c. 1750]‘…as at A, B and C. in Plate XXXII. which represents their Sections, if Plate XXXII [c. 1750]‘…as at A, B and C. in Plate XXXII. which represents their Sections, if](https://64.media.tumblr.com/aabb737414922ca3561f7319e2515f89/d6dd68496dcb729b-64/s500x750/c65382db2228b2c40702dedc7edc68fc25d6bf41.jpg)