#texas history

This article was written by kYmberly Keeton, who is a writer, independent publisher, and art librarian. A version of this article previously appeared in the Dallas Weekly, and kYmberly has updated it with her recent research findings. She notes, “I am also a native of Fort Worth, Texas–[Horace] lived there the majority of her life… I have had the opportunity to visit where she lived, did extensive research, read the book mentioned in the article, and now continuing on to include her in a forthcoming book that I am writing. I am the second author and only librarian to have documented her life at this point.”

The image is courtesy of the Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society.

Texas’ first African American woman novelist was also a biographer, diarist, educator, publisher, and librarian. Lillian B. Horace was born on April 29, 1880 in Jefferson, Texas. Her parents were Thomas Armstead and Mary Ackard. The family moved to Fort Worth, Texas when Lillian was a young toddler. She would go on to receive her early and formal education, graduating from the historically black institution, I. M. Terrell High School. Lillian enrolled in Bishop College in Marshall, Texas, where she took classes from 1898 to 1899. She focused her entire life around writing, entrepreneurship, community activism, philanthropy, and her faith.

Like most women in the south, Lillian B. Horace began her journey in education before she graduated from college. She taught in area schools in Fort Worth, Texas, for six years, and then traveled to different universities throughout the United States to further her education. Lillian received a Bachelor’s Degree in 1924 from Simmons University in Louisville, Kentucky. After graduating from college, Lillian B. Horace was appointed as Dean of Women at Simmons University for two years. She then returned to Fort Worth, Texas, to become the Dean of Girls at I.M. Terrell High School where she established the school’s library, journalism, drama departments and the school newspaper. Lillian B. Horace was a member of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Alphin Art and Charity Club, Progressive Woman’s Club, and the Order of the Eastern Star. Through all of Lillian B. Horace’s contributions in the community, little is known or has been publicized about her writing career until now. The writer’s papers are available in Fort Worth, Texas at the Genealogy, History & Archives Unit at the Fort Worth Public Library, and at the Tarrant County Black Genealogical Society.

During the early part of the 20th century, few African American women were known to carry the title of writer or entrepreneur in the south. Horace was a publisher and shared an office with James I. Dotson where they established the Dotson-Jones Printing Company. Lillian B. Horace self-published her first book in 1916, Five Generations Hence –a utopian novel. Lillian’s themes in her first body of work focused on black women’s education, philanthropy, economic self-empowerment, and social etiquette. She used her first novel as a platform for discussion about blacks returning to their origins – the continent of Africa. The writer began working on her second novel, Angie Brown, in the 1930’s; married a preacher, Joseph Gentry Horace of Groveton, Texas; and became a member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Club. The couple divorced and Lillian B. Horace continued writing and added another genre to her literary prowess: Biography.

Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams presented Lillian B. Horace with the opportunity to write his biography. In 1938, the writer began documenting his life, and produced Sun-Crowned: A Biography of: Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams, published in 1964, by L. Venchael Booth. In the writer’s own words at the beginning pages, she clearly expresses to the reader that this is an accurate portrait of the subject:

“This is not a report on notes gathered from out-of-the-way sources, nor an additional stroke to an already developed portrait. The subject stood before me a living, breathing human being, plodding this work-a-day world shackled by all superstitions, inhibitions, and privations and restrictions of a member of an underpriving group. I saw that he had the furnace finer than most given the same test, and he rose about the mediocrity that might have been his.”

Lillian B. Horace begins the biography with a stroke of prose about the life of Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams. His parents, Levi and Elizabeth Williams were both slaves; and were given their freedom in 1865, per the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln. They had seven children; Lacey Kirk Williams was the second son born on July 11, 1811. The writer provides the reader with information about the Williams family migration from the backwoods of Alabama to the southwest region of Texas. In like manner, the author states that she does her best to have the voice of an interviewer, but filled with the spirit of her faith, her talent for writing prose seeped into the biography to paint a portrait vividly for the reader, ultimately always wanting to offer an honest and thorough visual depiction of the subject’s life.

Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams received a major part of his education and life-skills, religion, society, and culture from Thankful Baptist Church, in Alabama. He received his formal education under the direction of a white church member that was originally from the east coast. His father was ordained as a deacon in the church and his mother became a prayer leader. They became a religious force in their community, gaining the trust of their peers. Levi Williams received with word from another well-known preacher that resided in their town about the opportunities given to newly freed slaves in the southwest region of Texas. He decided to leave his family for a brief time and visit the southwest, to check out the possibilities that were available for black people. In the late 1800’s, the Williams family migrated from the state of Alabama to Burleson County, Texas. Once there, young Lacey Kirk Williams attended a school that his father helped found, River Lane Public School. Their lives never were the same after they migrated to Texas.

Levi Williams would go on to run for County Commissioner, was into education, and ordained a reverend. Lacey Kirk Williams followed his father’s every move and mimicked a preacher every time a chance presented itself. Lillian B. Horace portrays his character from boyhood to a young man as a life filled with wisdom passed on from generations of slaves and freedmen. The young man’s journey as an educator and minister led him through many doors and cities; opportunities opened up for him in many ways. He married one of his pupils, Georgia Lewis; their families had migrated to the southwest together. As a family man, Lacey Kirk Williams took full advantage of everything that came his way, including passing the state educator’s exam, and receiving his call and license as a minister in December of 1894. In the early 1900’s the Baptist minister enrolled in Bishop College in Marshall, Texas, and supported his young wife’s quest for knowledge; she enrolled in a women’s school and became a student-teacher. Lacey Kirk Williams’ first sermon was given at a revival in Cookespoint, Texas.

Lillian B. Horace documents in the biography that Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams would go on to receive a D.D. degree from Selma University and an LL.D degree from Bishop College. He then began preaching on a full-time basis. During his tenure as a religious leader, he led congregations at Macedonia Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas in 1907 and then took over Mt. Gilead Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas in 1909. He was a leader and supporter of the Lincoln Association, Baptist Missionary, and the Educational Convention. Williams transitioned out of Texas to become pastor of Chicago’s Olivet Baptist Church in 1916; it was the largest Black church in the United States with 12,000 members. He went on to receive awards and accolades for his work in the black community on a national scale. Lacey Kirk Williams died shortly after accepting an award on October 29, 1940 in Flint, Michigan. He was buried at Lincoln Cemetery in Chicago.

Lillian B. Horace documented the southern migration of an African American male born to parents of slaves, his rise to prominence as a Baptist minister, and national leader. The biography is listed in The Papers of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Advocate for Social Gospel–referencing the work of the author.

Bibliography

Chernyshev, K. K. (2014, April 4). Horace, Lillian B. Retrieved from Handbook of Texas Online: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fhobi

Horace, L. B. (1995). Daring to Dream: Utopian Fiction by United States Women Before 1950. In C. F. Kesslee, Daring to Dream: Utopian Fiction by United States Women Before 1950 (pp. 175-186). Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press.

Horace, L. (1964). Sun-Crowned: Biography of Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams. Fort Worth: L. Venchael Booth.

The Mier Expedition: The Drawing of the Black Bean, Frederic Remington, 1896

September 5, 1836 - Sam Houston elected as president of Texas

“On this day in 1836, Sam Houston is elected as president of the Republic of Texas, which earned its independence from Mexico in a successful military rebellion.

Born in Virginia in 1793, Houston moved with his family to rural Tennessee after his father’s death; as a teenager, he ran away and lived for several years with the Cherokee tribe. Houston served in the War of 1812 and was later appointed by the U.S. government to manage the removal of the Cherokee from Tennessee to a reservation in Arkansas Territory. He practiced law in Nashville and from 1823 to1827 served as a U.S. congressman before being elected governor of Tennessee in 1827.

A brief, failed marriage led Houston to resign from office and live again with the Cherokee. Officially adopted by the tribe, he traveled to Washington to protest governmental treatment of Native Americans. In 1832, President Andrew Jackson sent him to Texas (then a Mexican province) to negotiate treaties with local Native Americans for protection of border traders. Houston arrived in Texas during a time of rising tensions between U.S. settlers and Mexican authorities, and soon emerged as a leader among the settlers. In 1835, Texans formed a provisional government, which issued a declaration of independence from Mexico the following year. At that time, Houston was appointed military commander of the Texas army.

Though the rebellion suffered a crushing blow at the Alamo in early 1836, Houston was soon able to turn his army’s fortunes around. On April 21, he led some 800 Texans in a surprise defeat of 1,500 Mexican soldiers under General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at the San Jacinto River. Santa Anna was captured and brought to Houston, where he was forced to sign an armistice that would grant Texas its freedom. After receiving medical treatment for his war wounds in New Orleans, Houston returned to win election as president of the Republic of Texas on September 5. In victory, Houston declared that “Texas will again lift its head and stand among the nations….It ought to do so, for no country upon the globe can compare with it in natural advantages.”

Houston served as the republic’s president until 1838, then again from 1841 to 1844. Despite plans for retirement, Houston helped Texas win admission to the United States in 1845 and was elected as one of the state’s first two senators. He served three terms in the Senate and ran successfully for Texas’ governorship in 1859. As the Civil War loomed, Houston argued unsuccessfully against secession, and was deposed from office in March 1861 after refusing to swear allegiance to the Confederacy. He died of pneumonia in 1863.”

This week in History:

September 2, 1969 - First ATM opens for business

September 3, 1777 - American Flag first flown in battle

September 4, 1886 - Geronimo surrenders

September 5, 1774 - First session of Continental Congress convenes

September 6, 1522 - Magellan’s expedition circumnavigates globe

September 7, 1864 - Atlanta is evacuated

September 8, 1974 - Ford pardons Nixon

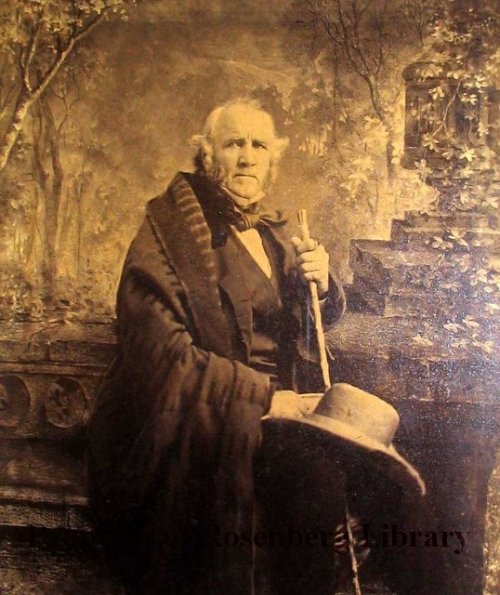

Thisphotograph of Sam Houston can be found in the collection of the Rosenberg Library.

Post link