#the man who made the beatles

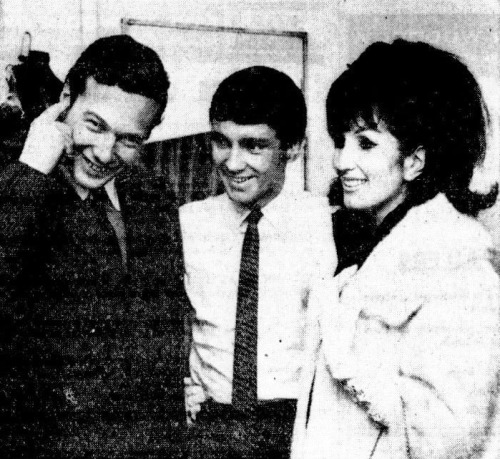

Brian EpsteinandAlma CogangreetGene Pitney backstage before his concert at the ABC Theatre, Harrow. (November 11, 1964)

‘Alma was a very finely attuned, mystical person and she thought Brian was too. Alma went to his home many times and was bemused by his collection of hundreds of suits. They spoke often on the phone; Brian valued Alma’s thoughts on many things.’

- Sandra Caron [Alma’s sister] (The Man Who Made the Beatles by Ray Coleman)

Post link

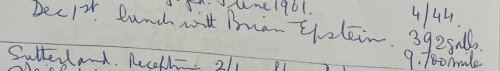

Colin Borland’s 1961 handwritten notes: Dec 1st: Lunch with Brian Epstein.

Epstein’s December 1 meeting with Decca Records’ Colin Borland (pictured below) and Sidney Beecher-Stevens kickstarted a chain of events which secured the Beatles an audition with the label.

December 1961 was a heady, frantic month. Juggling the signing of the Beatles with his EMI and Decca visits, while coping with the record shops and his puzzled father, Brian sprinted ahead looking for record company interest even before the Beatles had fully committed themselves to him; such was the ardour of his belief in them. At Decca, Brian had excellent relationships with two executives; Arthur Kelland, the regional sales manager based in Leeds, and Colin Borland, assistant to Sidney Beecher-Stevens, the London marketing chief. Again using his influence as a retailer, he phoned both men to say that the Beatles from Liverpool could be their British ‘answer’ to American pop dominance of the best-selling charts. He asked Arthur Kelland to arrange him an appointment in London to negotiate extra discounts for the records his shop bought from Decca. Provocatively Brian said he thought other dealers might be getting preferential treatment. This was untrue, but Kelland politely referred him to Colin Borland in head office.

On regular visits to Liverpool Borland had been impressed by Epstein’s enthusiasm and candidness: ‘I’m a failed actor and I’ve got to get the shops moving well.’ The Decca men thought him ‘too nice’ for the rough and tumble of retailing, but like the entire industry they admired his techniques; and his rising sales graph made beautiful reading. Brian had delegated many decisions to his shop manageress, Josephine Balmer; but he earned Borland’s respect by often telephoning him in London to ask precise reasons for Decca’s pressure on him to display promotional material on certain artists. ‘Why should I give you my window display? Are you going to do a big advertising campaign? He always wanted to ensure that he would reap a benefit from helping them.

And Borland always found Epstein convivial company. Unlike many provincial shop managers, Brian never opted for the most expensive restaurants when Borland visited Liverpool. He was happy with a simple trattoria. It was a fine example of his integrity, for it showed that Brian was not a grasper. Borland suggested lunch to discuss the request for discounts.

To his surprise and that of Beecher-Stevens, Brian arrived at their London office on 1 December 1961 and immediately dismissed the topic of discounts. That, he implied, was merely an excuse to get a chance to discuss something infinitely more important. It was the same tactic he had used with Ron White at EMI. ‘What I’m really interested in is getting records made by a group I’m managing.’ He produced a copy of the Liverpool pop paper, Mersey Beat, which featured a picture of the Beatles. ‘We were well aware,’ says Borland, ‘that this was the most important thing that had happened to him for a very long time.’

Epstein’s first proposal was revolutionary, and showed a visionary commercial streak that was unlike anything happening in the pop record business in 1961. He wanted Decca to make a record that would be exclusively licensed to him, perhaps on something called NEMS records. Borland said this would be difficult. If Decca recorded the Beatles, then as a major trading company they would have to make their records available to the whole retail trade. Brian said he was prepared to make it viable personally by buying 5,000 copies. Even with a discount, that would have cost him £1,050, an astronomically high figure in 1961 but an indication of his unshakeable confidence. Conceding that the record would have to go on general sale, he added: ‘All right, if I’m giving you this nice big offer, I want the records first and I want to be allowed to sell them where the Beatles are appearing.’ It was, says Borland, a big gamble which Epstein was prepared to take to demonstrate his enthusiasm.

To any record company, Epstein’s offer would have been very attractive. A guaranteed sale of 5,000 would be a flying start: some singles did not get that many pressed as an advance, or sell that number in total. Next Brian played Borland and Beecher-Stevens the Polydor single “My Bonnie.” Listen to the backing group, Brian urged them. Like Ron White at EMI, the executives found it hard to isolate them from the vocalist.

Still, Brian’s offer of 5,000 sales was music to the ears of salesmen. Borland lifted the phone to Dick Rowe, the company’s head of artists and repertoire. This resulted in another lunch, a few days later, in Decca’s senior executive club on Albert Embankment. Rowe joined them at the coffee stage. Well aware of Epstein’s status, he listened to his enthusiasm and said he would start wheels moving. He delegated the next step to his young A & R assistant Mike Smith, who confirmed to Brian that he would travel to the Cavern to judge the Beatles’ potential. It was a triumphant breakthrough - a London record executive on his way to Liverpool! Brian could scarcely wait to return home to break the news to the Beatles, who were equally excited.

-The Man Who Made the Beatles by Ray Coleman

[After seeing the Beatles at the Cavern, Mike Smith offered them a London audition. The ill-fated audition took place on New Year’s Day, 1962.]

Post link