#thrip pollination

When it comes to insect pollination, flowering plants get all of the attention. However, flowers aren’t the only game in town. More and more we are beginning to appreciate the role insects play in the pollination of some gymnosperm lineages. For instance, did you know that many cycad species utilize insects as pollen vectors? The ways in which these charismatic gymnosperms entice insects is absolutely fascinating and well worth understanding in more detail.

Cycads or cycad-like plants were some of the earliest gymnosperm lineages to arise on this planet. They did so long before familiar insects like bees, wasps, and butterflies came onto the scene. It had long been assumed that, like a vast majority of extant gymnosperms, cycads relied on the wind to get pollen from male cones to female cones. Indeed, many species certainly utilize to wind to one degree or another. However, subsequent work on a few cycad genera revealed that wind might not cut it in most cases.

It took placing living cycads into wind tunnels to obtain the first evidence that something strange might be going on with cycad pollination. The small gaps on the female cones were simply too tight for wind-blown pollen to make it to the ovules. Around the same time, researchers began noting the production of volatile odors and heat in cycad cones, providing further incentives for closer examination.

Subsequent research into cycad pollination has really started to pay off. By excluding insects from the cones, researchers have been able to demonstrate that insects are an essential factor in the pollination of many cycad species. What’s more, often these relationships appear to be rather species specific.

By far, the bulk of cycad pollination services are being performed by beetles. This makes a lot of sense because, like cycads, beetles evolved long before bees or butterflies. Most of these belong to the superfamily Cucujoidea as well as the true weevils (Curculionidae). In some cases, beetles utilize cycad cones as places to mate and lay eggs. For instance, male and female cones of the South African cycad Encephalartos friderici-guilielmi were found to be quite attractive to at least two beetle genera.

Beetles and their larvae were found on male cones only after they had opened and pollen was available. Researchers were even able to observe adult beetles emerging from pupae within the cones, suggesting that male cones of E. friderici-guilielmi function as brood sites. Adult beetles carrying pollen were seen leaving the male cones and visiting the female cones. The beetles would crawl all over the fuzzy outer surface of the female cones until they became receptive. At that point, the beetles wriggle inside and deposit pollen. Seed set was significantly lower when beetles were excluded.

For the Mexican cycad Zamia furfuracea, weevils also utilize cones as brood sites, however, the female cones go to great lengths to protect themselves from failed reproductive efforts. The adult weevils are attracted to male cones by volatile odors where they pick up pollen. The female cones are thought to also emit similar odors, however, larvae are not able to develop within the female cones. Researchers attribute this to higher levels of toxins found in female cone tissues. This kills off the beetle larvae before they can do too much damage with their feeding. This way, the cycad gets pollinated and potentially harmful herbivores are eliminated.

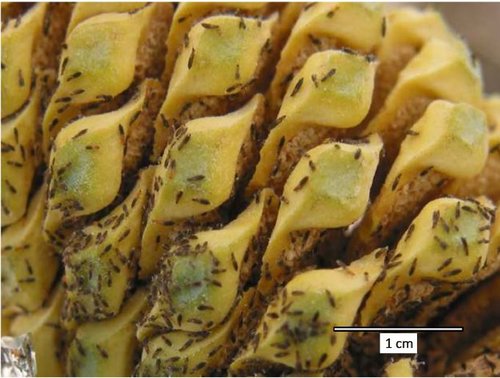

Beetles also share the cycad pollination spotlight with another surprising group of insects - thrips. Thrips belong to an ancient order of insects whose origin dates back to the Permian, some 298 million years ago. Because they are plant feeders, thrips are often considered pests. However, for Australian cycads in the genus Macrozamia, they are important pollinators.

Thrip pollination was studied in detail in at least two Macrozamiaspecies,M. lucidaandM. macleayi. It was noted that the male cones of these species are thermogenic, reaching peak temperatures of around 104 °F (40 °C). They also produce volatile compounds like monoterpenes as well as lots of CO2 and water vapor during this time. This spike in male cone activity also coincides with a mass exodus of thrips living within the cones.

Thrips apparently enjoy cool, dry, and dark places to feed and breed. That is why they love male Macrozamia cones. However, if the thrips were to remain in the male cones only, pollination wouldn’t occur. This is where all of that male cone metabolic activity comes in handy. Researchers found that the combination of rising heat and humidity, and the production of monoterpenes aggravated thrips living within the male cones, causing them to leave the cones in search of another home.

Inevitably many of these pollen-covered thrips find themselves on female Macrozamia cones. They crawl inside and find things much more to their liking. It turns out that female Macrozamia cones do not produce heat or volatile compounds. In this way, Macrozamia are insuring pollen transfer between male and female plants.

Pollination in cycads is a fascinating subject. It is a reminder that flowering plants aren’t the only game in town and that insects have been providing such services for eons. Additionally, with cycads facing extinction threats on a global scale, understanding pollination is vital to preserving them into the future. Without reproduction, species will inevitably fail. Many cycads have yet to have their pollinators identified. Some cycad pollinators may even be extinct. Without boots on the ground, we may never know the full story. In truth, we have only begun to scratch the surface of cycads and their pollinators.