#ugly sweater

When the Ling Space team had the idea for some linguistics-themed Christmas apparel, the chance to syntax-ify the lyrics to ‘O Christmas Tree’ was just too good to pass up. Being the resident syntactician, I got to work on figuring out exactly what the structure for that opening line should look like. The “Christmas tree” part’s easy enough; that “O” turned out to be a very different story.

More below the fold!

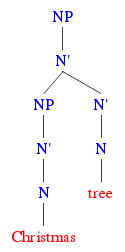

Like we’ve talked about before, the theory that linguists developed back in the 1970s had it that every kind of phrase fit into the same basic shape — the X-bar schema. This meant that even simple nouns like “tree” would have a structure that looks like this:

That might seem like we’ve needlessly put a very small word into a very big house, but that extra room is crucial when determiners, adjectives, and prepositional phrases come over to visit:

With English being pretty easy-going when it comes to more than one noun living under the same roof, we’ve got our Christmas tree:

And with more recent developments in syntactic theory, like the DP Hypothesis discussed back in Episode 79, we have some good reasons to think that even bare noun phrases are actually cozily packaged up inside determiner phrases, like a present waiting to be unwrapped (think about how, in morphologically richer languages like French, even a simple phrase like “trees” needs an article before it, as in ”les arbres”):

But what about that “O”? What is it, even? Some version of “oh”? And where should it go?

At first, I just assumed it was an interjection (like “wow”) — one of the eight parts of speech that make up traditional grammar. Not that I’d thought about it much up until now, mind you. But, that seemed to be a reasonable guess. Problem is, the expression “oh” is typically associated with fear, surprise, or delight. In this case, it looks more like it’s pointing out the addressee, which is the person (or thing) being, well, addressed. After all, the accompanying lyrics mostly go on to describe the eponymous tree. That “O” looks to be doing the same job here that it’s doing in Canada’s national anthem ‘O Canada,’ or Walt Whitman’s poem ‘O Captain! My Captain!’

The good news is, linguists have a name for this! That “O” is a vocative particle. The bad news? That doesn’t mean much. The word “vocative” is there to point out that we’re dealing with vocative phrases, which are typically used to explicitly address the person being spoken to. In the lyric below, from the 1953 song ‘Santa Baby,’ that first bit functions as a vocative phrase, addressing the whole song to Santa Claus.

(1)Santa baby, slip a sable under the tree for me

English doesn’t oblige us to use “O,” but many languages regularly make use of such words. Catalan employs the particles “ei” and “eh.” Irish uses “a.” And, in fact, the “O” we’re currently interested in is just a carry-over from the original German ‘O Tannenbaum.’

But “particle”? That’s just what linguists call anything that they don’t know what it is. The infinitival marker “to” in English is sometimes called a particle, along with many other words in many other languages. By itself, it doesn’t tell us much. So what does the literature on this stuff have to say?

Unfortunately, as it turns out, there doesn’t really seem to be much research to speak of. And what little there is doesn’t seem to point to much of a consensus on the matter. So, how did we settle on the structure for our shirt? Well, to start, there seems to be a fundamental disagreement about the nature of vocative phrases: are they constituents?

Informally, a constituent is just a string of words that behave as a group. And on the surface, it might seem strange to question whether or not such phrases are bound together. But consider the following Italian data; while language generally allows any two like phrases to connect together with an “and” sandwiched between them, vocatives resist the trend.

(2a) O MariaePietro, Gianni è arrivato.

o Maria and Pietro, Gianni is arrived

(2b) *O Mariaeo Pietro, Gianni è arrivato.

o Maria and o Pietro, Gianni is arrived

Italian lets you double up on what’s inside the phrase (2a), but you can’t do the same for the whole thing over (2b). For some, this suggests that vocative particles aren’t really part of the noun phrases they’re coupled with, and instead form part of the structure of the overall clause. That way, only one ever rears its head, in the same way questions only ever have enough room for one set of question-y words at a time (3); “what will” and “when will” can’t coordinate with each other, since neither pair forms a constituent, with each word instead occupying a pre-determined position inside the sentence.

(3a)What will you be giving them Christmas Day?

(3b)When will you be giving them gifts?

(3c) *What willandwhen will you be giving them?

The general blueprint of sentences, then, would limit the number of particle-y vocatives to exactly one, at the very top, above everything else.

Still, others insist our dear “O” is closer to its noun phrase than to the clause that follows. And since it’s hard to make a shirt out of a non-constituent, we took the path of least resistance. That still leaves us with an open question, though: if vocative phrases are just bulked up noun phrases, why put the “O” up at the top, instead of putting it inside that empty Voc position a bit lower down? If anything’s going to form the core part of a vocative phrase, shouldn’t it be our particle?

Enter Latin. Many languages mark their vocatives with affixes instead of particles. William Shakespeare’s famous line “Et tu, Brute?” in the play ‘Julius Caesar’ has “Brutus” in his vocative form, with that “-e” replacing the nominative suffix “-us.” Other languages, like Romanian, can both directly mark their nouns (e.g., “grandpa”) as vocative, while also making use of a particle:

(4) bre tataie

PRT grand’pa.VOC

The takeaway is that the information that a phrase is being used vocatively spreads our across two separate positions — one that can connect up directly to the noun, and one that shows up beside it. (French negation works similarly, as in “Ils n'aiment pas Noël.”) Any given language can make use of one of these positions (Latin), the other (archaic English), neither (Modern English), or both (Romanian).

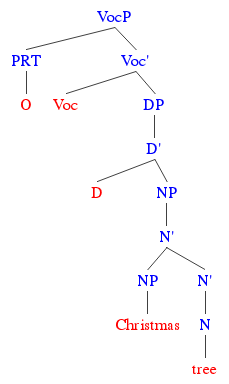

In cases where the noun bears an affix, we suppose it’s moved up out of the NP/DP combo and into that Voc position, so that (4)’s structure looks something like this:

We can tell this is probably the right way to think about what’s going on, since names in Romanian (e.g., “Ion”) contain information related not only to their being marked as vocative, but to their being definite (i.e., as though they’ve picked up a hitchhiking article along their way up the tree):

(5) Ionelule

Ionel.the.VOC

So, at last, we have our structure for “O Christmas tree.” Without any vocative affixes to speak of in English, the nouns stay put, and our lovely little particle “O” perches itself up on the highest branch. Mix in some atelierMUSE magic, et voilà!

not gunna lie i would def make this a sticker even if no one was interested because i love this sketch so much and would buy it for myself

(thank you for whoever asked this and made this drawing come into my head space)

Post link

Insta:@littlebigrower

Christmas gucci cookie

If your “ugly” Christmas sweaters just make you look all the more fuckable, you might be a bimbo.

Merry Christmas!

Post link

Another ugly jumper to add to my ever growing collection. Not the ugliest though.

credits:expressionsrealia

Post link