#welsh literature

Poem from Llanybri

If you come my way that is …

Between now and then, I will offer you

A fist full of rock cress fresh from the bank

The valley tips of garlic red with dew

Cooler than shallots, a breath you can swank

In the village when you come. At noon-day

I will offer you a choice bowl of cawl

Served with a ‘lover’s’ spoon and a chopped spray

Of leeks or savori fach, not used now,

In the old way you’ll understand. The din

Of children singing through the eyelet sheds

Ringing smith hoops, chasing the butt of hens;

Or I can offer you Cwmcelyn spread

With quartz stones from the wild scratchings of men:

You will have to go carefully with clogs

Or thick shoes for it’s treacherous the fen,

The East and West Marshes also have bogs.

Then I’ll do the lights, fill the lamp with oil,

Get coal from the shed, water from the well;

Pluck and draw pigeon, with crop of green foil

This your good supper from the lime-tree fell.

A sit by the hearth with blue flames rising,

No talk. Just a stare at 'Time’ gathering

Healed thoughts, pool insight, like swan sailing

Peace and sound around the home, offering

You a night’s rest and my day’s energy.

You must come – start this pilgrimage

Can you come? – send an ode or elegy

In the old way and raise our heritage.

'Poem from Llanybri’, Lynette Roberts

(1944)

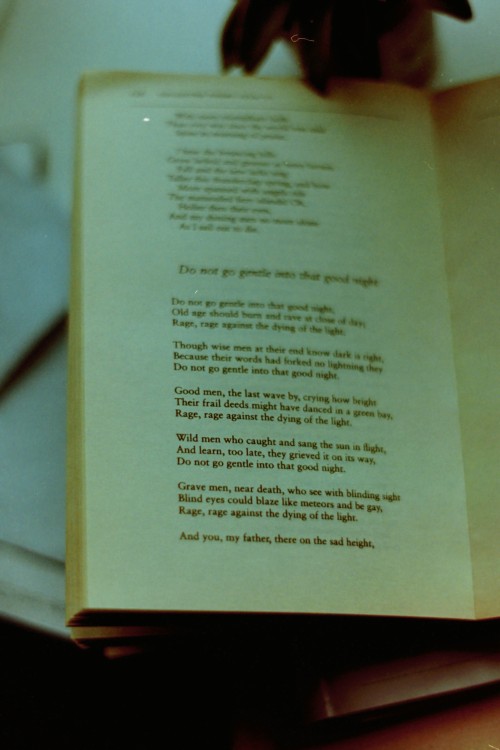

‘Do not go gentle into that good night’, Dylan Thomas

(1951)

After the two nephews had been cleaned up they went to see Math, who said, ‘Men, you have earned peace, and you shall have friendship. Now advise me which virgin to choose.’ Gwydyon replied, 'Lord, that is an easy choice: Aranrhod daughter of Dôn, your niece and your sister’s daughter.’ The girl was sent for, and when she arrived Math said, 'Girl, are you a virgin?’ 'I do not know but that I am.’ Math took his wand and bent it, saying, 'Step over that, and if you are a virgin I will know.’ Aranrhod stepped over the wand, and with that step she dropped a sturdy boy with thick yellow hair; the boy gave a loud cry, and with that cry she made for the door, dropping a second small something on the way, but before anyone could get a look at it Gwydyon snatched it up and wrapped it in a silk sheet and hid it in a little chest at the foot of his bed. 'Well, ’ said Math, 'I will arrange for the baptism of this one,’ referring to the yellow-haired boy, 'and I will call him Dylan.’ The boy was baptized, whereupon he immediately made for the sea, and when he came to the sea he took on its nature and swam as well as the best fish. He was called Dylan son of Ton, for no wave ever broke beneath him. The blow which killed him was struck by his uncle Govannon, and that was one of the Three Unfortunate Blows.

'Math Son of Mathonwy’, The Mabinogion

c. 11th century

trans. Jeffrey Gantz (1976)

Dylan Thomas, The Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas: The New Centenary Edition; from ‘In Country Sleep’

Dylan Thomas, The Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas: The New Centenary Edition; from ‘Light breaks where no sun shines’