#18 century music

Co-stars & Rivals: V I T T O R I A T E S I

- Stage name: La Moretta, La Fiorentina

- Born:Florence, 13 Feb 1700

- Died:Vienna, 9 May 1775

- Voice:contralto

- Personality:Vittoria Tesi was an Italian opera singer and music teacher of the 18th century, endowed by nature with a strong, masculine contralto voice thus she created many travesti parts, In 1738 she refused for a time to sing any more of them on the grunds that ‘acting a male part is bad for her health’. Her operatic career began with performances at Parma and Bologna in 1716. By 1718 she was virtuosa di camera for the Prince of Parma at Venice. The following year she was at Dresden, singing for Antonio Lotti alongside Senesino and Margherita Durastanti, where she performed arias which are generally set for basses. By 1721 she was back in Italy for the Florentine Carnival, and for the next 26 years travelled Europe, with performances in Madrid and possibly Frankfurt. Italy, however, was the nation where she spent most of her time, dividing the years between its various cities. In 1725 in Naples, together with Farinelli, she premiered Hasse’s serenata Marc'Antonio e Cleopatra. Her career peaked in the late 1730s and 1740s, when she sang alongside such singers as Caffarelli; in 1744 she took the title role in Gluck’s Ipermestra and did the same in 1748 in his Semiramide riconosciuta, set to a libretto by Metastasio. This performance persuaded Metastasio of her merits, although previously he had been unenthusiastic, calling her a “grandissima nullità”. After successful performances in Niccolò Jommelli’s Achille in SciroandDidone abbandonata (1749), both set to Metastasian libretti, Tesi began to retire from the stage. In 1751 she became costume director at the Viennese court, where she remained for many years, teaching music as a particular favourite of Countess Maria Theresia Ahlefeldt. Among her pupils were Caterina Gabrielli and Elisabeth Teyber, and she is known to have met not only Casanova but also Mozart and his father.

- One fact: Tesi is said tomarry a simple Italian guy, in order to fend off the advances of an undesired nobleman (according to Burney her husband was a “poor journeyman baker” who was picked off the street and paid fifty ducats for marrying the singer, “not with a view to their cohabiting together”.)

- One quote: “She was perhaps the first actress who acted well while singing badly"(Sarah Goudar)

- One hit:Attendi ad amarmi (Marc'Antonio e Cleopatra)

Post link

Co-stars & Rivals: A N N A G I R Ò

- Born:Mantua, c1710

- Died:after 1747

- Voice:contralto

- Personality: Anna Girò is known above all for her professional association with Antonio Vivaldi - a relationship suspected, at the time, of carrying over into their private lives, although modern research suggests the opposite. Anna’s father was a wig-maker of French extraction. The singer’s actual name was Teseire – Italianized to Tessieri – whereas Giro was a sobriquet her father had used. About 1722 she went to Venice to study singing, living with an elder half-sister, Paolina, who acted as her chaperone. She made her operatic début in Treviso in autumn 1723; her first appearance on the Venetian stage was in Albinoni’sLaodice (autumn 1724). Giro sang in over 50 operatic productions. She started, in her early teens, with minor travesty roles, then graduated to seconda donna and soon also to prima donna roles. Vivaldi, for whom she sang (nearly always as prima donna) in over 30 productions from 1726 to 1739, appears to have been her principal mentor. He once declared, with evident exaggeration, that he could not put on an opera without her, but she was well able to operate independently of him, as she proved during his transalpine tour of 1729 - 31 (when Giro was performing alongside Farinelli in Broschi’s Ezio and Porpora’s Poro) and again after his death in 1741. Her very successful career lasted until 1748, when, after singing in Piacenza at Carnival, she married a widowed count from that city, Antonio Maria Zanardi Landi, and retired honourably from the stage.

- One fact: The amendments to the libretto of Zeno’sGriselda that Vivaldi instructed Goldoni to make in 1735 were designed to hide her defects and promote her strengths.

- One quote: She was not pretty, but she had charms, a very slim waist, beautiful eyes, lovely hair, a charming mouth, and a small voice, but a great deal of acting ability. (Carlo Goldoni)

- One hit: Svena, uccidi, abbatti, atterra (Bajazet)

Post link

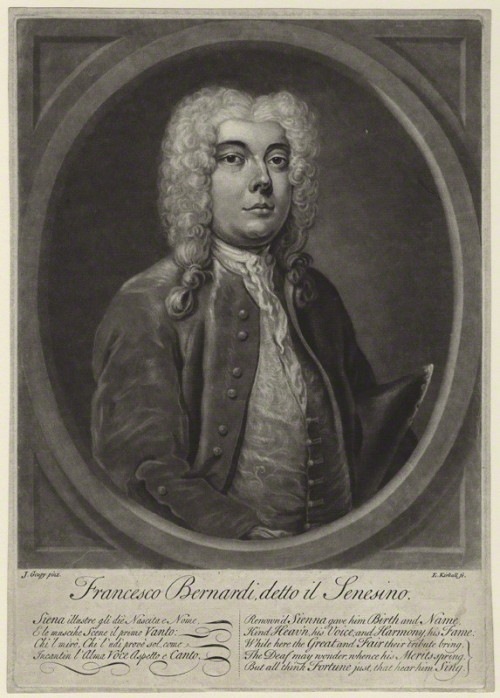

The brief history of Castrati - part three (part one,part two)

Serious opera in the first two-thirds or so of the 18th century was dominated by a succession of famous castratos, of whom Nicolo Grimaldi (’Nicolini’), Antonio Maria Bernacchi, Francesco Bernardi (’Senesino’), Carlo Broschi (’Farinelli’), Giovanni Carestini, Gaetano Majorano (’Caffarelli’) and Gaetano Guadagni are only the best known. Such artists could command engagements in one European capital after another at unprecedented fees - in Turin the primo uomo’s fee for the carnival season was sometimes equal to the annual salary of the prime minister - while they also kept, as insurance, permanent appointments in a monarch’s chapel choir or a cathedral, and some of them performed there regularly.

Their achievements are now difficult to gauge. Their command of vocal agility - of trills, runs and ornamentation, especially in the da capo section of an aria was clearly central to their success. So, at least for some, was a phenomenally wide range: Farinelli is said to have commanded more than three octaves (from c to d’“), others more than two, though, like some modern sopranos and tenors, they were apt to lose the upper part of their range as their careers wore on. It would, however, be a mistake to regard leading castratos as vocal acrobats and no more. Command of pathetic singing - soft, laden with emotion, powered by controlled devices such as messa di voce - was highly regarded: it was, for instance, central to the reputation of Gasparo Pacchiarotti. Nor was acting ability ignored: Guadagni’s performance as Gluck’s original Orpheus was thought deeply affecting. The issue is clouded by the habit of commentators through most of the 18th century of bemoaning the supposed decadence of opera through an excessive cult of vocalism and ornamentation. This was in part a literary convention. The cult flourished, and was in practice forwarded by some of those who decried it.

Another contemporary habit that needs to be guarded against is that of mocking the castratos as grotesque, extravagant, inordinately vain near-monsters. This was in part a nervous reaction against a phenomenon experienced as sexually threatening twice over: the fact of castration was disconcerting in itself, yet according to legend (held by most modern medical opinion to be baseless, though perpetuated, along with much traditional obfuscation, in the 1995 film Farinelli) castratos could perform sexually all the better for the loss of generative power. In part the mockery visited upon castratos was roused by highly paid star singers in general, among whom they were the most prominent. Because of their musical education they often did well as teachers; some who had also had a general education acted in retirement, or even during their singing careers, as antiquarian, booksellers, diplomats, or officials in royal households.

Post link