#castrato

Castrato

Castrato (del italiano castrato, ‘castrado’; castrati en plural) es la denominación que se utiliza para referirse al cantante sometido de niño a una castración para conservar su voz aguda (de soprano, mezzo-soprano o contralto). El término tradicional español (hoy en desuso) referido a estos cantantes era capón. Actualmente se emplea la voz italiana.

Lacastración consistía en la destrucción o ablación del tejido testicular sin que, por lo general, se llegara a cortar el pene. Mediante esta intervención traumática, se conseguía que los niños que ya habían demostrado tener especiales dotes para el canto mantuvieran, de adultos, una tesitura aguda capaz de interpretar voces características de papeles femeninos. De este modo se lograba aunar la aguda voz infantil, considerada tierna y emocional, con las cualidades de un intérprete adulto que un niño difícilmente podía igualar: mayor potencia pulmonar, pleno dominio de la voz y la sabiduría propia de la edad.

Post link

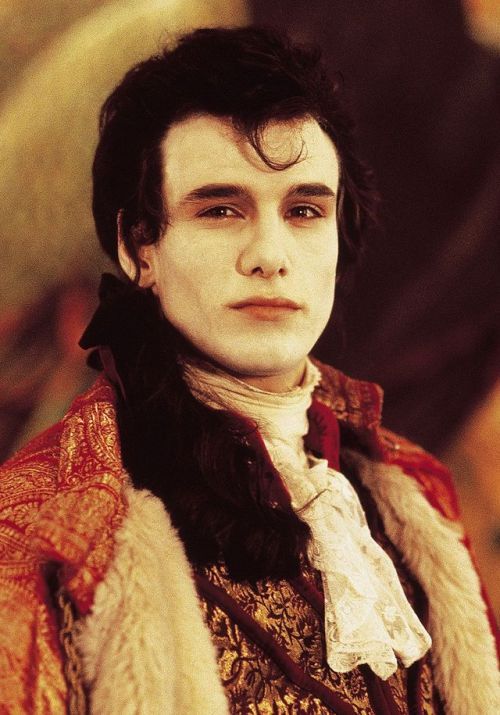

Fanart herein! I just read Stephanie Burgis’s historical fantasy Masks and Shadows, which is a pretty awesome story set in 1770s Hungary, about how romance blooms between an Italian castrato and an Austrian widow when they meet at the court of Esterhazy. And there’s magic and alchemy and Gothic horror too. Highly recommended!

Anyway, I love the central romance, and after I finished reading the story I couldn’t get the main characters (Carlo Morelli, the castrato, and Charlotte von Steinbeck, the widow) out of my head. So here they are. I really want a sequel!

Post link

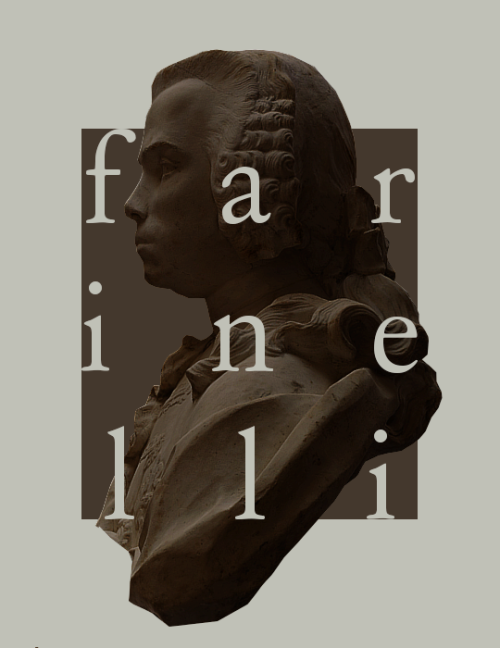

Jacopo Amigoni (Napoli, 1682 – Madrid, 1752)

FERDINANDO VI DI BORBONE AND BARBARA DI BRAGANZA WITH THE COURT (including Farinelli and Scarlatti on the balcony)

oil on canvas, cm 46,5x61

source:https://www.pandolfini.it/it/asta-0338/jacopo-amigoni.asp

Post link

Blue: Peace, tranquility, cold, calm, stability, harmony, unity, trust, truth, confidence, conservatism, security, cleanliness, order, loyalty, sky, water, technology, depression, appetite suppressant.

Post link

The Osuna Palace in Aranjuez

The Osuna Palace in Aranjuez is a neoclassical building that was built in 1751 for Italian artist Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi. He was better known under his stage name Farinelli. The palace was built by the architect Giacomo Bonavia who also created the royal palace ‘Palacio Real de Aranjuez’. After Farinelli’s banishment from the Spanish court the building became the property of the Crown for twenty years. Then it was aquired byt the IX duke of Osuna. It remained in the hands of the dukes of Osuna until Mariano Téllez-Girón, XII Duke of Osuna, who doomed to ruin, had to sell it.

In May 2018 there was a huge fire at the palace. The intense fire caused the roof to collapse. Eight fire crews were trying to prevent the flames spreading to neighbouring properties. The palace itself was lost.

Sources (+ more pictures): XXX

Post link

Co-stars & Rivals: G I Z Z I E L L O

- Real name: Gioacchino Conti

- Born:Arpino, 28 Feb 1714

- Died:Rome, 25 Oct 1761

- Voice:soprano

- Personality:Conti was one of the greatest of 18th-century singers. He was an exceptionally high soprano with a compass of at least two octaves (c’ to c’“) and the only castrato for whom Handel wrote a top C.His nicknames derived from Domenico Gizzi, who taught him singing. Conti’s début at Rome in Vinci’s Artaserse (1730) was a spectacular success. His subsequent career led him throughout Italy, as well as abroad. In 1736–37 he was in London, where he had been engaged by George Frideric Handel, with whom he would build a profitable collaboration. The press reported that he met with an uncommon Reception; the poet Gray admired him ‘excessively’ in every respect except the shape of his mouth, which ‘when open, made an exact square’. Gizziello sang at many premieres for the best and most famous musicians of his time, including Niccolò Jommelli, Baldassare Galuppi and Johann Adolf Hasse. In 1749 he was invited by Farinelli to sing at Madrid with Mingotti; and stayed there three years. Conti always remained in good terms with Farinelli, who repeatedly invited him to Spain, terming him "Antiguo amigo” (longtime friend). From 1752 to 1755 he was employed by the Lisbon court theatre and sang in many operas, most of them by Perez; he is said to have narrowly escaped with his life from the Lisbon earthquake (1755), and was impressed with such a religious turn by the tremendous calamity, that he retreated to a monastery, where he ended his days (Burney), but not before he had imparted much sage and practical counsel to Guadagni. His retirement may, however, have been due to ill-health.

- One fact: In character Conti was the antithesis of Caffarelli, being as gentle as the latter was overbearing. However, a colourful anecdote relates how Caffarelli, rode post-haste to Rome from Naples just to attend incognito Conti’s debut; and full of enthusiasm eventually yelled at him: “Bravo, bravissimo Gizziello, it’s Caffariello who’s telling you!”

- One quote: Gizziello was ‘so modest and diffident, that when he first heard Farinelli, at a private rehearsal, he burst into tears, and fainted away with despondency’ (Burney)

- One hit:Non sono sempre vane larve (Arminio)

Post link

I found this small, unobtrusive painting while looking through Collection of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. The work is said to be executed around 1740 - 1745, and is attributed to Pietro Longhi - a Venetian painter, who mastered the portrayal of scenes of everyday Venetian life.

This picture depicts such of those scenes – in the dimly lit room a group of people enjoys themselves with music (yes, to me it looks more like a casual afternoon music session than a tutelage). The central part of the picture presents a lady (a young girl?) and a gentleman, both clad more glamorous than the other two sitters, and more visible because of the light that falls directly on them. Behind the pair stands the man in the long wig with the violin in his hands, while in the margin of the picture, by the harpsichord we can observe another person, lurking at us from a deep shadow – the only one element that creates some kind of tension. From the ceiling, placed right beetwen the Shadowman and the Harpsichordist, the cage with the trapped bird is hanged…

Without doubt, the main character of the scene is a young - looking man playing harpsichord – who appears to be quite tall even while sitting, and his half-opened, dark eyes glance at the lady by his side, but there is nothing threatening nor sexual in that stare…The musician stature, the pose, the fashionable wig, the blue color of his coat decorated with gold, and mostly the soft face with the dark, thick eyebrows and slightly absent look in the eyes – all that reminds me too much of Farinelli! Of course this could be just a coincidence, but if you compare Jacopo Amigoni’s portrayals of the singer to the mysterious musician from the Longhi’s work,…

…It tells much!

And there is also the pose – it is almost a faithful copy of Farinelli’s legs setting in the most famous picture of him, showing the singer gathered with his friends in the Spanish garden in 1750. Farinelli sits in a similar way in the earlier picture from 1735 as well.

If it’s not enough the harpsichord player wears a ring on his little finger. The one appears also on Carlo Broschi’s hand in another of Amigoni’s paintings done in 1750. And finally, the harpsichord! The very similar looking instrument Farinelli touches in the Bartolomeo Nazari’s image, created in Venice in 1734. Both paintings have also a second common element - the dog - an animal that Carlo clearly loved and kept in his household for all of his life.

Of course, the date of the picture doesn’t fit, but this could be just a mistake of someone who did the inventory. The painting is described as made during the 1740s. Farinelli was at the Spanish court then and stayed there until 1759, while Longhi (according to the informations I could find) left Venice only once, in his younger years, to become an apprentice of the Bolognese painter Giuseppe Maria Crespi. It was before 1732. But…if we examine the biography of Broschi’s boys – both Carlo and Riccardo were staying in Bologna during that time. Could they possibly acquainted Longhi then?

Another, and more possible scenario is, that the painter met them after his return to Venice in 1732, and before Farinelli’s departure to England in 1734. Longhi was not a well-known artist yet, but he turned his attention to the genre painting in 1730s, so portraying the famous castrato around 1734 could be possible! The violinist also looks strangely similar to Thomas Osborne, duke of Leeds, who was a music lover and a crazy Farinello groupie (minus the sexual content!), who attented all of the castrato’s performances while he was in Italy.

Both men soon became friends, so could this picture be commisioned by the Duke? Maybe the aristocrat was a host of a private music party, during which the castrato performed before the English visitors (the lady looks very English if you ask me)? Or maybe he was Farinelli’s guest in Venice? There is a chest or a suitcase lying in the corner of the picture, with the music scores on it. It gaves the feeling that the musician is a visitor or a traveller (both terms matching the status of the big opera star), but it also reminds me strongly of the term suitcase arias…The text written on the sheets is very hard to read, this could be a signature of the painter, but the arrangement of the letters looks a little like a fragment taken from one of those Farinelli’s suticase arias called “Cervo in Bosco” (in bosco se l’imipiaga), used in the operas Medo and Catone in Utica. The latter one performed in…Venice.

What about the Shadowman then? This could be no other than Riccardo Broschi, one of those who were responsible of turning Carlo Broschi into a human nightingale Farinelli…And thus always living in his castrated brother’s shadow…

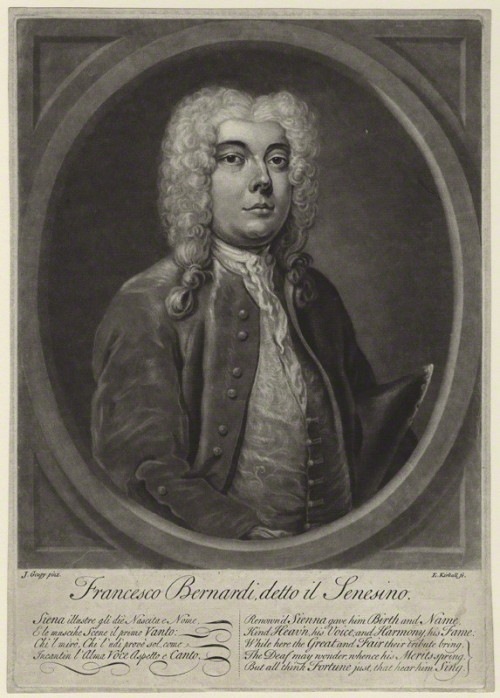

The brief history of Castrati - part three (part one,part two)

Serious opera in the first two-thirds or so of the 18th century was dominated by a succession of famous castratos, of whom Nicolo Grimaldi (’Nicolini’), Antonio Maria Bernacchi, Francesco Bernardi (’Senesino’), Carlo Broschi (’Farinelli’), Giovanni Carestini, Gaetano Majorano (’Caffarelli’) and Gaetano Guadagni are only the best known. Such artists could command engagements in one European capital after another at unprecedented fees - in Turin the primo uomo’s fee for the carnival season was sometimes equal to the annual salary of the prime minister - while they also kept, as insurance, permanent appointments in a monarch’s chapel choir or a cathedral, and some of them performed there regularly.

Their achievements are now difficult to gauge. Their command of vocal agility - of trills, runs and ornamentation, especially in the da capo section of an aria was clearly central to their success. So, at least for some, was a phenomenally wide range: Farinelli is said to have commanded more than three octaves (from c to d’“), others more than two, though, like some modern sopranos and tenors, they were apt to lose the upper part of their range as their careers wore on. It would, however, be a mistake to regard leading castratos as vocal acrobats and no more. Command of pathetic singing - soft, laden with emotion, powered by controlled devices such as messa di voce - was highly regarded: it was, for instance, central to the reputation of Gasparo Pacchiarotti. Nor was acting ability ignored: Guadagni’s performance as Gluck’s original Orpheus was thought deeply affecting. The issue is clouded by the habit of commentators through most of the 18th century of bemoaning the supposed decadence of opera through an excessive cult of vocalism and ornamentation. This was in part a literary convention. The cult flourished, and was in practice forwarded by some of those who decried it.

Another contemporary habit that needs to be guarded against is that of mocking the castratos as grotesque, extravagant, inordinately vain near-monsters. This was in part a nervous reaction against a phenomenon experienced as sexually threatening twice over: the fact of castration was disconcerting in itself, yet according to legend (held by most modern medical opinion to be baseless, though perpetuated, along with much traditional obfuscation, in the 1995 film Farinelli) castratos could perform sexually all the better for the loss of generative power. In part the mockery visited upon castratos was roused by highly paid star singers in general, among whom they were the most prominent. Because of their musical education they often did well as teachers; some who had also had a general education acted in retirement, or even during their singing careers, as antiquarian, booksellers, diplomats, or officials in royal households.

Post link

The brief history of Castrati - part two (part one)

From about 1680 the expectation, eventually the rule, was that the leading male part in a serious opera (primo uomo) should be sung by a castrato; there might be a less important secondo uomo part, also for a castrato, with tenors singing the parts of kings and old men. This was also the period when Italian opera came to be given fairly regularly both in Italy and in those parts of Europe under Italian musical influence - in the German-speaking countries and the Iberian peninsula, from about 1710 in London, from the 1730s in Sankt Petersburg. The best castratos therefore became international stars, welcomed and highly paid in all the leading courts and capital cities, with the notable exception of Paris (where, after Cardinal Mazarin’s attempts at importation in the mid-17th century, they were not allowed to appear in opera; some leading castratos gave concerts when they were passing through, and some much more modest ones remained on the king’s musical establishment as church singers until the Revolution).

The reasons for this new dominance of the castrato voice are interrelated. Italian composers of the period 1680 - 1720 began to write operas calling for more technically demanding coloratura singing; the range expected of leading singers widened, and the tessitura generally rose, as it was to go on doing (for both men and women) through most of the 18th century. Virtuoso castratos were now available in numbers in the service of princes who promoted frequent opera seasons: Giovanni Francesco Grossi (”Siface”) and Francesco Antonio Mamiliano Pistocchi were only the most prominent among a new group of star singers. It was still possible at this time for a famous castrato not to sing in opera at all, like Giovanni Battista Merola, active in Naples in the late 17th century, or, like Matteo Sassano (”Matteuccio”), whose career lasted from 1684 to 1711, to do so only occasionally. But from then on a famous castrato was in the first place an opera singer. Church choirs had increasingly to grant their best castratos leave to sing in opera.

Castratos occasionally appeared in comic opera but (outside Rome) normal voices were there the rule. In the newly refined genre of serious opera, on the other hand, the castrato voice with its special brilliance appears to have struck contemporaries as the right medium to convey nobility and heroism. Objections, when they came, were to the incongruity of castratos in general - or, on moral grounds, to their singing of womens parts - rather than to their appearance as heroes or lovers.

Post link