#after edward

Who was Quentin Crisp?

George Nichols is the Assistant Director of Tom Stuart’s new play, After Edward, a response to Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II for which George is also the Assistant Director.

In this blog he looks at key characters from After Edward that were real people. At the heart of this he and the cast have been asking how much they should impersonate these real people and how much they should interpret them.

Quentin Crisp (played by Richard Cant in After Edward) was born into an inauspicious suburban family, the son of a solicitor and a governess; however, he went on to live an extraordinary life. He is now best known as a raconteur, writer and actor whose appearance and personality defied gender norms.

Crisp recounted that he was the subject of much bullying in his early life because of his effeminate behaviour. After leaving school in the 1920s Crisp moved to Soho where he met other young homosexual men and found more freedom to be able to wear women’s clothing and makeup. By his own account his appearance shocked Londoners and led to him being the victim of homophobic attacks. During this time Crisp also sold sex as a rent boy, he said in an interview later in his life that he was ‘looking for love, but found only degradation’.

In the rehearsal room we’ve talked a lot about the effect that Crisp’s early life might have on his character in After Edward. We keep returning to the feeling of personal invalidity felt by the characters because their way of being goes against the grain of society. As one character says ‘the world is made for white, male heterosexuals’.

Before gaining public recognition, Crisp tried to enlist in the army in the early 1940s but was given a medical exemption on grounds of ‘sexual perversion’. It was in this period that Crisp became a life model for artists, something he would continue to do for 30 years.

Crisp’s fame came later in his life, following the publication of his book The Naked Civil Servant and its subsequent screen adaptation starring John Hurt. Following this he toured regularly with his show An Evening with Quentin Crisp, where he would perform for the first half before taking audience questions in the second. Crisp also became successful across the Atlantic and eventually he moved to New York. In New York, as in London, Crisp’s name and phone number were listed in the public directory. Crisp saw it as a duty to answer all calls and turn up to all invites, so as long as you paid for it all you had to do was pick up the phone to have him over for dinner.

This aspect of his personality was something that fascinated us. Was it because he loved conversation, or did it cover a hole in his personal life? We know from his own admission that he never quite felt loved or cared for. It’s here too that we see distinctions between the character of Quentin Crisp in our play, and the real life figure.

Crisp died aged 91 near Manchester as he was preparing for the revival of his one man show An Evening with Quentin Crisp. Throughout his old age he had remained thoroughly outrageous and thought provoking and Richard Cant’s performance marries these elements to a deeply affecting softness that makes Crisp sparkle.

After Edward opens in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on 21 March.

Photography by Marc Brenner

Post link

Complicity in Edward II.

In this blog Assistant Director George Nichols of Edward II asks, should the audience feel complicit in Edward’s shocking death?

How would a 17th-century audience have reacted to being included in the political machinations of Richard III? How is an audience meant to feel after laughing at Malvolio’s humiliation in Twelfth Night? What about at Edward II’s grizzly death?

The productions of these plays that I find most affecting are those in which the audience feels complicit in the action of the play. Really, I think this should be a guiding principle throughout all theatre, as writers, directors and actors should think of the audience not as observers, but as participants.

Complicity is definitely something we learn about from the unique stages at the Globe. The proximity of the audience to the stage and the fact that in many instances you must push through or walk past audience to get into the space suggests that the complicity of the audience was a key aspect in how these plays were originally performed. It’s also inherent in the texts; soliloquies, for example, show us that characters were in a constant dialogue with the audience. By letting us in on a clandestine plot as Edmund does in King Lear, it creates dramatic irony through the fact that we are privy to something that the other characters are not.

In our production of Edward II the idea of the audience being participants had to take the fore, not least because of the number of characters we had to cut from the text. In some cases, to accommodate these cuts we changed pronouns from ‘we/ they’ to ‘I/ me’ etc, but occasionally we felt there were opportunities to open the play out to the audience. For example, the barons often refer to a number far greater than themselves, and so in our production they address the audience as their accomplices, at other points we have changed the allegiance of some characters to aid with the flow of the story, and so in one instance the audience becomes Edward’s friends, replacing lost allies in the play.

The shows played before press night when the media review the play are an interesting time for any production, but at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse they are particularly significant. Whilst all pre-press night shows are to some extent a method of gauging how a production sits with an audience, in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse you feel guided toward what their role is in the action through their particular mood or the atmosphere. As we get more experience of the reaction we get, the more the actors learn which lines work as direct challenges to audience members, and which lines are best kept in the space. There’s beauty in the fact that it can be different for each performance once you establish that the audience is flexible and can be friend or foe depending on what you need in that moment.

Once this relationship is established you can use all sorts of techniques to keep an audience on board; soliloquies, asides or even humour. But sometimes, the most effective tool you have is just to pose a direct question. After watching the suffering Edward goes through, being entertained by and complicit in his downfall, how do you feel when he turns to you and asks: ‘Pity you me?’

Edward II is in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse until 20 April. Tom Stuart’s contemporary response to Marlowe’s play, After Edward, opens on 21 March.

Photography by Marc Brenner

Post link

Voices in the Dark: Pride, Then and Now.

How relevant are Shakespeare and his contemporaries today? That is the question we ask in Voices in the Dark, an ongoing festival of events and performances that run alongside our main-stage productions.

Voices in the Dark examines the nature of Shakespeare’s transformative impact on the world through an ongoing dialogue, a call and response, between today’s artists and Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

This spring in our latest iteration of the Voices in the Dark festival, Pride, Then and Now we respond to After Edward, in itself a response to Marlowe’s Edward II - a play that is rare in its depiction of a gay relationship on the early modern stage.

Moll and the Future Kings

Kicking off proceedings in spectacular style on 30 March is Moll and the Future Kings - an hour of late-night drag king cabaret and improv, by candlelight.

Moll Frith, also known as Mal Cutpurse, fascinated her 17th-century audiences when, in 1611, she appeared on stage during a production of The Roaring Girl, Middleton and Dekker’s play about her life. An improvised moment involving rude jokes, songs and smoking, this is the only known professional playhouse performance by an English woman.

Performed by members of the Through the Door course, this work-in-progress, this experiment, this conversation with our queer early modern past celebrates Moll the cross-dressing performer, criminal and trickster and all those like her.

Curated by Sarah Grange with Clerkinworks, and supported by Shakespeare’s Globe and Improbable.

Hear more about Moll and the Future Kings from event curator Sarah Grange and drag king Wesley Dykes in the latest episode of our podcast. Transcript available.

Buy tickets for After Edward in the same transaction and save £2 on tickets for Love is LoveandMoll and the Future Kings.

Wanton poets and pleasant wits: Edward II now

On 4 April, following the 7.30pm performance of After Edward, join us for a free post-show discussion chaired by our Research Fellow Dr Will Tosh.

Bringing together some of today’s most exciting queer thinkers and writers, we will reflect on the legacy of Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II.

This event is free to ticket-holders for that evening’s performance of After Edward and also, subject to space in the auditorium, everyone else who is interested in attending without seeing the preceding performance.

Love is Love

On 6 April London’s a cappella LGBT+ choir, The Fourth Choir, returns to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse to mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in June 1969.

In a celebration in words and music of LGBT+ lives and loves, Love is Love roams through nine centuries taking influence from Hildegarde of Bingen in the 12th century to jazz legend Billy Strayhorn in the 20th.

Coupled with music by composers such as Poulenc, Tchaikovsky and Rufus Wainwright, Love is Love brings to life hidden histories: the woman put on trial in 18th-century Germany for marrying another woman; history’s most extraordinary bisexual love triangle; the famous composer who liked to wear drag; and the Stonewall Warriors themselves.

Buy tickets for After Edward in the same transaction and save £2 on tickets for Love is LoveandMoll and the Future Kings.

Image credit: Ellan Parry

Sarah Grange, curator of Moll and the Future Kings and drag king Wesley Dykes discussed the inspiration behind the show on our podcast, Such Stuff .

Post link

By Candlelight.

George Nichols is the Assistant Director for Edward IIandAfter Edward. He is writing a blog series about the processes and ideas in these two plays.

In this blog, George gives insight into how candles will be used to light Edward II which will be staged in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse.

Obviously, the importance of lighting in theatre goes far beyond just allowing you to see the actors on the stage (although that is a vital function!). A casual theatregoer may not realise how significant lighting is, and how it fundamentally shapes the tone and feel of a production. In a conventional production, a good creative team work closely, so that action, space, sound and lighting are inextricable. Often, if a lighting design is doing its job you won’t notice it at all. Lighting at its best is a fluid accompaniment to movement, a best friend to design and a vehicle for expression.

So how does the unique candle lighting of the Sam Wanamaker playhouse affect the way we stage texts? Well, firstly it’s important not to think of candles as a restriction. Even though you have a very small range of paintbrushes, you have a huge and varied palette to paint from. Anyone who has seen Macbeth, which is running currently, will be able to attest to how ingeniously candlelight can be used.

In the playhouse there are six three-tiered chandeliers that can be lowered or raised, several sconces fixed to pillars which provide a small amount of light, hand-held candles and torches to be carried by actors as well as long footlights that sit at the front of the stage and reflect light upwards. All these light sources can be used in conjunction with each other, and each different combination has a different effect.

We’re always thinking about these different effects during Edward II rehearsals. The locations in the play all have different qualities of light, both literally and tonally, as we move from coronations to battlefields and abbeys to dungeons. Lighting candles takes time, so to flood the space with light or get rid of a lot of light you need to think of ways of incorporating candle lighting or snuffing into the action of the play. The lighting of candles can be a joy to watch, but it can quickly become panicked if a candle won’t light, so we have sessions in the space to make sure the cast all feel comfortable with lighting and holding candles. Open flames can be dangerous, so in these sessions, actors are reminded not to use petroleum based hair products, lest they go up in flames!

There are numerous challenges and quirks that come with candlelight. For example, a blackout can feel intense in a normal theatre, but in the playhouse, we also must keep in mind the fact that everyone is very close together, and that the smell of beeswax and sometimes incense can add another layer of intensity. This makes the use of darkness more of a statement. It’s pretty difficult to do in the middle of a half because you then have to work out a way to bring a lot of light back in to the space. However, we’re very fortunate that our director, Nick Bagnall, has a lot of experience of working in the playhouse. He’s able to quickly turn these challenges to our advantage, reinforcing the principle of seeing candlelight not as a restriction but as a unique opportunity.

Edward II opens in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on 7 February.

Post link

Staging Renaissance plays in the 21st century: Meanings of words.

George Nichols is the Assistant Director for Edward IIandAfter Edward. He is writing a blog series about the processes and ideas in these two plays.

In this blog, George discusses the meaning of words, how they have changed and what impact that has on stage. In further blogs, he looks at understanding the etiquette of the time the play is set (14th century) and the importance of the Church and the feudal system.

Edward II was written in the 16th century, set in the early 14th century and will be performed to a 21st-century audience in a building that has the central goal of recreating the performance conditions of the early modern stage.

This convoluted series of perspectives brings with it a number of challenges and questions. For example, how do we deal with obscure allusions and references? How do we work with words that are no longer in common usage or now have different meanings? How do we stage peculiar and antiquated codes of etiquette from the day?

Meanings

It sounds obvious, but the Oxford English Dictionary can be one of your most valuable tools in staging renaissance drama. In the full OED you can not only find the definition of every word in existence but the changing usage of each word through the last 1000 years. Of course, if a word has an archaic definition it’s unlikely the audience will know that no matter how the line is played. However, knowing the precise definitions of words and occasionally their dual meanings can give us insight into the relationships between characters, illuminate jokes, or crystallise meaning. Take, for example, the word ‘minion’. This is the kind of word that we think we know. A cursory Google search brings up the definition:

a follower or underling of a powerful person, especially a servile or unimportant one.

This is how we would mostly use this word today (Despicable Me films aside). However, if you look up this word in the full OED you get, among others, the following definitions:

- A (usually male) favourite of a sovereign, prince, or other powerful person; a person who is dependent on a patron’s favour; a hanger-on.

- A male or female lover. Also (frequently derogatory): a man or woman kept for sexual favours; a mistress or paramour.

- A fastidious or effeminate man; a fop, a dandy.

All of these were in usage when Edward II was performed, and so the fact that Isabella frequently calls Edward’s male lover Gaveston ‘minion’ takes on a new significance. It tells us more about what those at court think about the relationship between Gaveston and Edward, not only from the perspective of sexuality but also of what is proper from a hierarchical perspective.

It’s often the words you think you know that yield up the most interesting rewards. From other productions I have worked on I can remember us finding out the word ‘fire’ was synonymous with venereal disease. Some of this knowledge will not be helpful for the audience, but most of it can offer the actor a new perspective on the lines they are playing.

Edward II, written by Christopher Marlowe will be directed by Nick Bagnall. After Edward, a contemporary response to Marlowe’s piece was written by Tom Stuart and will be directed by Brendan O'Hea. Tom will play Edward in both productions. The cast will be the same for both plays.

Post link

Staging Renaissance plays in the 21st century: Church and the Feudal system.

George Nichols is the Assistant Director for Edward IIandAfter Edward. He is writing a blog series about the processes and ideas in these two plays.

In this blog, George discusses the relevance of the Church and the Feudal system in 14th century England. In further blogs, he looks at the importance of understanding the etiquette of the time the play is set and the meaning of words and how they have evolved.

Edward II was written in the 16th century, set in the early 14th century and will be performed to a 21st-century audience in a building that has the central goal of recreating the performance conditions of the early modern stage.

This convoluted series of perspectives brings with it a number of challenges and questions. For example, how do we deal with obscure allusions and references? How do we work with words that are no longer in common usage or now have different meanings? How do we stage peculiar and antiquated codes of etiquette from the day?

Church and the Feudal system

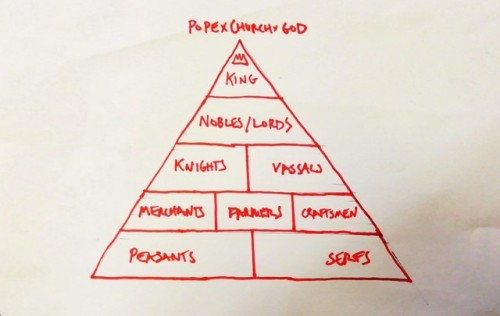

In the medieval period, societal order was structured in a hierarchical triangle known as the feudal system. At the top we have the king, believed to be appointed by the church and god; the king’s right to rule and the right of his heir to inherit the throne is known as the divine right of kings. This was common knowledge among our company, however, something we knew less about was the specific relationship between the church and monarchy. You can see from the diagram above that this hierarchy is supposedly ordained by God, but what happens if a king wants to get rid of an archbishop or make changes to the church? The answer to this is more convoluted as the king and the church seem to validate each other. If a king wants to be rid of an archbishop they must get permission from Rome, and when the monarch tried to do things like tax the church or change its structure Rome often voiced its displeasure.

In our cut of Edward II, we’ve tried to bring the church to the fore, partly for clarity of storytelling and partly because it’s a fascinating aspect of the play. But how does the above research contribute to the way we stage Edward II?

Well, something we grasp from both Marlowe’s play and the real life of Edward II is that civil war and deposition were highly unusual and that the stakes of this play must be extremely high. From our research, we know that the final power the church had available was to excommunicate the King, and thus end the divine right of his successors. By using this, or at least being aware of it in the scenes between the Archbishop of Canterbury and King Edward, we can heighten the stakes and ramp up the tension for the audience.

Edward II, written by Christopher Marlowe will be directed by Nick Bagnall. After Edward, a contemporary response to Marlowe’s piece was written by Tom Stuart and will be directed by Brendan O'Hea. Tom will play Edward in both productions. The cast will be the same for both plays.

Post link

Staging Renaissance plays in the 21st century: Etiquette.

George Nichols is the Assistant Director for Edward IIandAfter Edward. He is writing a blog series about the processes and ideas in these two plays.

In this blog George looks at the importance of understanding the etiquette of the time the play is set. In further blogs he discusses the relevance of the Church and Feudal system in 14th century England and the meaning of words and how they have evolved.

Edward II was written in the 16th century, set in the early 14th century and will be performed to a 21st-century audience in a building that has the central goal of recreating the performance conditions of the early modern stage. This convoluted series of perspectives brings with it a number of challenges and questions. For example, how do we deal with obscure allusions and references? How do we work with words that are no longer in common usage or now have different meanings? How do we stage peculiar and antiquated codes of etiquette from the day?

Not only is it difficult to answer these questions because we’re making our best-educated guesses about the world the play was written in, but also because Marlowe was writing about a period he likewise didn’t live in.

Engaging with these questions is something at the heart of what the Globe experiment is all about, and in week one of rehearsals for Edward II they’ve certainly been a central preoccupation of ours. As the assistant director, a lot of the responsibilities of research fall to me. Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been doing a lot of work on the etiquette of the court during the 14th century, the relationship between church and monarchy, the feudal system and 16th-century definition of words with the intention of contributing to the fabric of the world of the play. We’ve then worked to interpret what is most important about this information and how it can best be translated or used to create a coherent and, of course, enjoyable production.

Etiquette

Etiquette from the 14th century is positively barmy, although they might say the same thing about today. It’s easy to forget that we still obey a code of etiquette that we perceive as innate behaviour, but which is actually socially determined; just think about the way we queue, the way we dress or the way we behave in the workplace.

In medieval England, there were a number of writings about proper conduct for people from all different walks of life. Some of these instructions sound ridiculous, for example in Daniel Beccles 3000 word poem The Etiquette of Man, it stipulates:

In front of grandees, do not openly excavate your nostril by twisting your fingers.

And in The Book of Courtesy it says:

Don’t put up at a red (haired and faced) man or woman’s house.

These are some of the silliest examples, but if we get bogged down in etiquette then we can quickly end up in a place where the play becomes difficult to stage, and where we leave the audience thoroughly confused. What’s important is to understand the role etiquette plays in Edward II and how we can best use it to tell the story effectively. By working on when the rules are followed and when they are broken, we can emphasise a threat to social order, an integral theme of the play.

Edward II, written by Christopher Marlowe will be directed by Nick Bagnall. After Edward, a contemporary response to Marlowe’s piece was written by Tom Stuart and will be directed by Brendan O'Hea. Tom will play Edward in both productions. The cast will be the same for both plays.

Post link

Shame.

George Nichols is the Assistant Director for Edward IIandAfter Edward. He is writing a blog series about the processes and ideas in these two plays.

Edward II, written by Christopher Marlowe will be directed by Nick Bagnall. After Edward, a contemporary response to Marlowe’s piece was written by Tom Stuart and will be directed by Brendan O'Hea. Tom will play Edward in both productions. The cast will be the same for both plays.

‘You can marry, you can adopt, you can say you’re gay in the workplace, but what about the things we haven’t had to time to deal with? The insidious things like shame that affect us silently every day?’

It’s the first week of rehearsals for After Edward,a production that will be performed in tandem with Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. After Edward is a new play, written by Tom Stuart (who will be playing Edward) and featuring a cast that will run across both productions. We’re talking a lot about the relationship between Tom’s play and Marlowe’s and what unites them across a void of 400 years and what makes them so important for audiences today.

Some background. Edward II, the central character of Marlowe’s play, has a same-sex romantic relationship with, among others, Piers Gaveston. It’s an amazing play, not least for what it tells about gender and sexuality in the Renaissance period in which the play was written, and the earlier 14th century when the play was set. A big question we’re grappling with this week is what connects the experiences of Edward II, Marlowe and a gay man living in the modern era?

Each of these different periods has a vastly different perspective on gender and sexuality (something we’ll cover in the next blog) and so each of these people will have had a vastly different experience. In fact, in the era the play was written people weren’t labeled because of the acts they committed; all people were considered capable of all things and so an act didn’t define an individual. Yet one thing that remains true across the last 700 years is that at no point has the preference for same-sex relationships been a societal norm. Whether homosexuality has been accepted, tolerated, persecuted or hidden the society we live in has primarily been designed with white heterosexual men in mind.

The effect that living up to a hetero-normative ideal has on the individual that doesn’t fit is something that resonates throughout these plays. That effect is, among other things, shame.

We’re fortunate that our company is made up of people with different personal perspectives on gender and sexuality. At some point though, we can all attest to having felt shame of some kind at being unable to live up to an ideal that is thrust upon us.

Despite the progress that can be said to have been made in the 21st century, for the plethora of people who do not identify with heterosexual ‘norms’ it can be impossible to see oneself in the surrounding cultural and social environment. Just think of something like the couplings on Strictly Come Dancingor the way the sex education in schools is almost entirely based around the heterosexual experience. Not seeing yourself in the world can have the impact of making you feel that the life you want to live is not only abnormal but wrong.

Later in the week, we talk to Dr. Will Tosh from the Globe’s Research Department about how some productions eschew the homosexuality within Edward II entirely and make Gaveston and Edward’s relationship platonic. We agree this is a shame. One of the great connections we have found with both Edward II andAfter Edwardis how important they both are for allowing people to see themselves in the culture around them. As one of the company says, with regards to their first reading of After Edward:‘I wish I had seen this play when I was growing up’.

Tom began this week by telling us a story of him standing in Berkley Castle, where Edward II was executed, and looking around and thinking ‘this is where it happened, this is where he was, he would have seen this light and felt this darkness’. In After Edward,the characters often come back to the idea that they are just one part of a long and never-ending line; from the pornographic petroglyphs unearthed by archaeologists to Edward II himself. In the modern world, we live in it is important that these lives and stories are shared and celebrated, and that we make the world a place where no one feels shame for who they are or the life they lead. It’s essential that this belief is a guiding principle of the work we create and the culture we share.

Post link

Edward II/After Edward Cast.

Edward IIandAfter Edwardwill be performed by the same cast of actors. Nick Bagnall will direct Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II and Brendan O’Hea will direct After Edward, written by Tom Stuart in response to Edward II.

Examining ancestral relationships and notions of identity, sexuality and power, Marlowe’s Edward II sees King Edward recall his lover, Gaveston, from banishment, setting in motion a chain of events that culminate in some of the most shocking scenes in early modern theatre.

Tom Stuart’s new play After Edward, written specifically for the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse in response to Edward II, sees Edward return to the stage alone, bloodied and confused. He has no idea where he is, or how he got here, but he does have an ominous feeling that something is wrong.

Annette Badland will play Mortimer Senior in Edward II and Gertrude Stein in After Edward

Richard Bremmer will play Archbishop of Canterbury/ Spencer Senior in Edward II and Archbishop of Canterbury/Leather Man in After Edward

Richard Cant will play Earl of Lancaster in Edward II and Quentin Crisp in After Edward

Polly Frame will play Earl of Kent in Edward II and Harvey Milk in After Edward

Jonathan Livingstone will play Mortimer Junior in Edward II and Edward Alleyn in After Edward

Sanchia McCormack will play Earl of Warwick in Edward II and Margaret Thatcher in After Edward

Colin Ryan will play Spencer Junior in Edward II and Cowboy in After Edward

Tom Stuart will play Edward II in Edward II and Edward in After Edward

Beru Tessema will play Gaveston in both Edward II and After Edward

Katie West will play Queen Isabella in Edward II and Dorothy Gale and Maria Von Trapp in After Edward

TheEdward II Company will also include:

Nick Bagnall as Director

Bill Barclay as Composer

Kevin McCurdy as Fight Director

George Nicholls as Assistant Director

Wayne Parsons as Choreographer

Jessica Worrall as Designer

TheAfter Edward Company will also include:

Laura Moody as Composer

George Nichols as Assistant Director

Brendan O’Hea as Director

Tom Stuart as Writer

Siân Williams as Choreographer

Jessica Worrall as Designer

Edward II opens in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on 7 February.

After Edward opens in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on 21 March.

Post link