#ancient tomb

Brief History On Japanese Graves

A friend of mine requested to write a post regarding how general graves, tombs, and cemeteries in Japan have evolved over time in chronological order.

(Discretion: Images of human remains)

ー Jōmon Period (and prior)

Most of the cemeteries during this period were simple, community burial ground with stones surrounding the location like the ones seen in Hajime-sawashita Site [はじめ沢下遺跡] (Midori Ward [緑区], Sagamihara City [相模原市], Kanagawa Prefecture) above. Corpses buried underground are discovered resting in different positions where some had their body curved in an “U” shape which is a style referred to as Kussō [屈葬] or flexed burial while others such as the one below from Mid-Jōmon Period in Inariyama Site [稲荷山貝塚] (Minami Ward [南区], Yokohama City [横浜市], Kanagawa Prefecture) are positioned with all their four limbs stretched out which is called Shintensō [伸展葬] or extended burial.¹

ー Yayoi Period〜Kofun Period

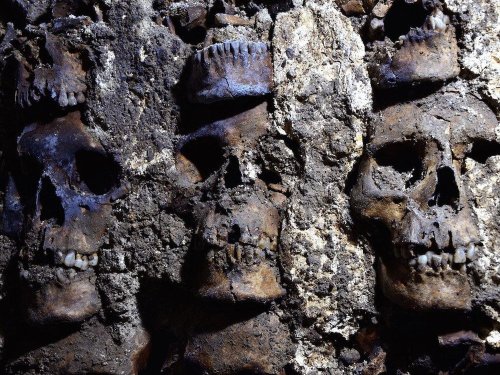

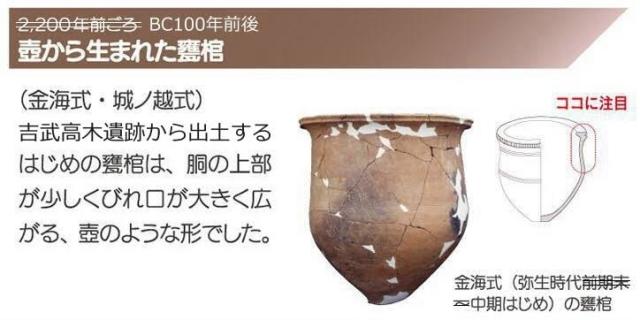

This is the period in Japanese history when coffins began to appear as well as the diversification of burial methods. At the end of Jōmon Period and throughout Yayoi period, Kamekanbo [甕棺墓] or “jar burial” like the ones above discovered in Yoshinogari Historical Park [吉野ヶ里歴史公園] (Yoshinogari Town [吉野ケ里町], Kanzaki Dist. [神崎郡], Saga Prefecture) becomes a common sight where jars/pots made of clay functions as a coffin used predominantly for placing deceased children² and there are two types of designs: Tankan [単棺] design like the one below left from Yoshitake-takagi Site [吉武高木遺跡] (Nishi Ward [西区], Fukuoka City [福岡市], Fukuoka Prefecture) where the corpse is inserted in a single jar/pot³ and Awaseguchi-kan [合口棺] design like the one below right from Nishioda Site [西小田遺跡] (Chikushino City [筑紫野市], Fukuoka Prefecture) where the opening of two separate jars/pots are conjoined together and sealed with pasting an additional clay around the brim to form a single coffin⁴.

Another common coffins from Yayoi Period (which is then carried on to Kofun Period) are stone coffins like the recently excavated ones in Nagai Site [長井遺跡] (Yukuhashi City [行橋市], Fukuoka Prefecture) below and the unique feature of each coffins are that the corpse are found divided into three separate segments⁵; a custom that was unprecedented up until the excavation of this cemetery in year 2019. Motive behind this custom is currently unknown due to it being discovered just recently.

ー Kofun Period〜Heian Period

Though the burial custom amongst commoners haven’t changed that much since Yayoi Period, this time period is when “mega-mausoleum” prepared for ancient monarchs began to appear. Such as the famous Daisenryō-kofun [大仙陵古墳] above in Sakai City [堺市] (Ōsaka) where Emperor Nintoku [仁徳天皇] is believed to lay rest. However, not all Kofun are as large as the one in Sakai City like Yonezuka-kofun [米塚古墳] in Iwata City [磐田市] (Shizuoka Prefecture) below which is comparatively far more smaller and obscure.

Although, these forms of mausoleums or any tombs in general, even began to shrink in size as well as becoming more simplistic due to the introduction of Buddhism and cremation where burnt bone dusts were collected then stored in pots/jars before burring⁶. Like with this Nara〜Heian Period grave below in Babawatauchi-yato Site [馬場綿内谷遺跡] (Tsurumi Ward [鶴見区], Yokohama City [横浜市], Kanagawa Prefecture), but not much is known aside from it being predominantly practiced by nobles.

(I’ve hit the maximum number of images in one post. So, the blog will continue on the reblogged post. Sorry for the inconveniences)

Sources:

1.“Jōmon-jidai-no-haka” [縄文時代の墓] via Kanagawa Archeology Foundation [かながわ考古学財団] (official)

2.Via Yoshinogari Historical Park [吉野ヶ里歴史公園] (official)

4.“”

5.Via Nishinippon-shinbun [西日本新聞] (news article)

6.“Nara Heian-jidai-no-haka” [奈良・平安時代の墓] via Kanagawa Archeology Foundation [かながわ考古学財団] (official)

7. “Ana-no-kōkogaku Yagura…” [穴の考古学 やぐら・横穴・洞穴の謎をさぐる] (1970) by Naotada Akahoshi [赤星 直忠] (1902-1991)

8. “Chūsei-toshi-kamakura…” [中世都市鎌倉-遺跡が語る武士の都] (1995) by Shinjirō Kawano [河野 真知郎] (n/a)

9.“Waseda-wīkurī” [早稲田ウィークリー] (2019) by Waseda University [早稲田大学] (academic article online)

Aztecs Constructed Tower Made Out of Hundreds of Human Skulls Discovered

Researchers in Mexico City recently discovered a new section of a macabre late 15th-century structure.

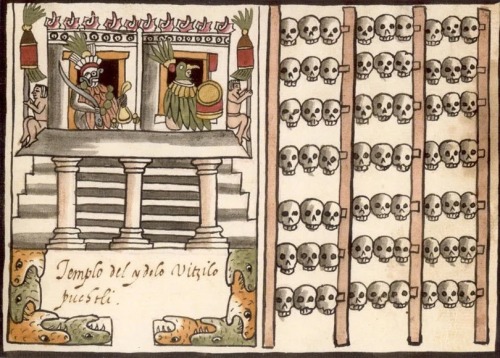

Archaeologists excavating a famed Aztec “tower of skulls” in Mexico City have uncovered a new section featuring 119 human skulls. The find brings the total number of skulls featured in the late 15th-century structure, known as Huey Tzompantli, to more than 600, reports Hollie Silverman for CNN.

The tower, first discovered five years ago by archaeologists with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), is believed to be one of seven that once stood in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. It’s located near the ruins of the Templo Mayor, a 14th- and 15th-century religious center dedicated to the war god Huitzilopochtli and the rain god Tlaloc.

Found in the eastern section of the tower, the new skulls include at least three children’s craniums. Archaeologists identified the remains based on their size and the development of their teeth. Researchers had previously thought that the skulls in the structure belonged to defeated male warriors, but recent analysis suggests that some belonged to women and children, as Reuters reported in 2017.

“Although we cannot determine how many of these individuals were warriors, perhaps some were captives destined for sacrificial ceremonies,” says archaeologist Barrera Rodríguez in an INAH statement. “We do know that they were all made sacred, that is, they were turned into gifts for the gods or even personifications of the deities themselves, for which they were dressed and treated as such.”

As J. Weston Phippen wrote for the Atlantic in 2017, the Aztecs displayed victims’ skulls in smaller racks around Tenochtitlán before transferring them to the larger Huey Tzompantli structure. Bonded together with lime, the bones were organized into a “large inner-circle that raise[d] and widen[ed] in a succession of rings.”

While the tower may seem grisly to modern eyes, INAH notes that Mesoamericans viewed the ritual sacrifice that produced it as a means of keeping the gods alive and preventing the destruction of the universe.

“This vision, incomprehensible to our belief system, makes the Huey Tzompantli a building of life rather than death,” the statement says.

Archaeologists say the tower—which measures approximately 16.4 feet in diameter—was built in three stages, likely dating to the time of the Tlatoani Ahuízotl government, between 1486 and 1502. Ahuízotl, the eighth king of the Aztecs, led the empire in conquering parts of modern-day Guatemala, as well as areas along the Gulf of Mexico. During his reign, the Aztecs’ territory reached its largest size yet, with Tenochtitlán also growing significantly. Ahuízotl built the great temple of Malinalco, added a new aqueduct to serve the city and instituted a strong bureaucracy. Accounts describe the sacrifice of as many as 20,000 prisoners of war during the dedication of the new temple in 1487, though that number is disputed.

Spanish conquistadors Hernán Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Andrés de Tapia described the Aztecs’ skull racks in writings about their conquest of the region. As J. Francisco De Anda Corral reported for El Economista in 2017, de Tapia said the Aztecs placed tens of thousands of skulls “on a very large theater made of lime and stone, and on the steps of it were many heads of the dead stuck in the lime with the teeth facing outward.”

Per the statement, Spanish invaders and their Indigenous allies destroyed parts of the towers when they occupied Tenochtitlán in the 1500s, scattering the structures’ fragments across the area.

Researchers first discovered the macabre monument in 2015, when they were restoring a building constructed on the site of the Aztec capital, according to BBC News. The cylindrical rack of skulls is located near the Metropolitan Cathedral, which was built over the ruins of the Templo Mayor between the 16th and 19th centuries.

“At every step, the Templo Mayor continues to surprise us,” says Mexican Culture Minister Alejandra Frausto in the statement. “The Huey Tzompantli is, without a doubt, one of the most impressive archaeological finds in our country in recent years.”

By Livia Gershon.

Post link