#and whats gayer than that

Memory of a Cool Evening, in 1941

I decided I’m going to post some of my writing here after all! ✨

Luiza remembers an evening at home in Latvia, before she died. [MCGA OCS]

“Luiza!”

The voice rings out across the field to reach her, and Luiza remembers this.

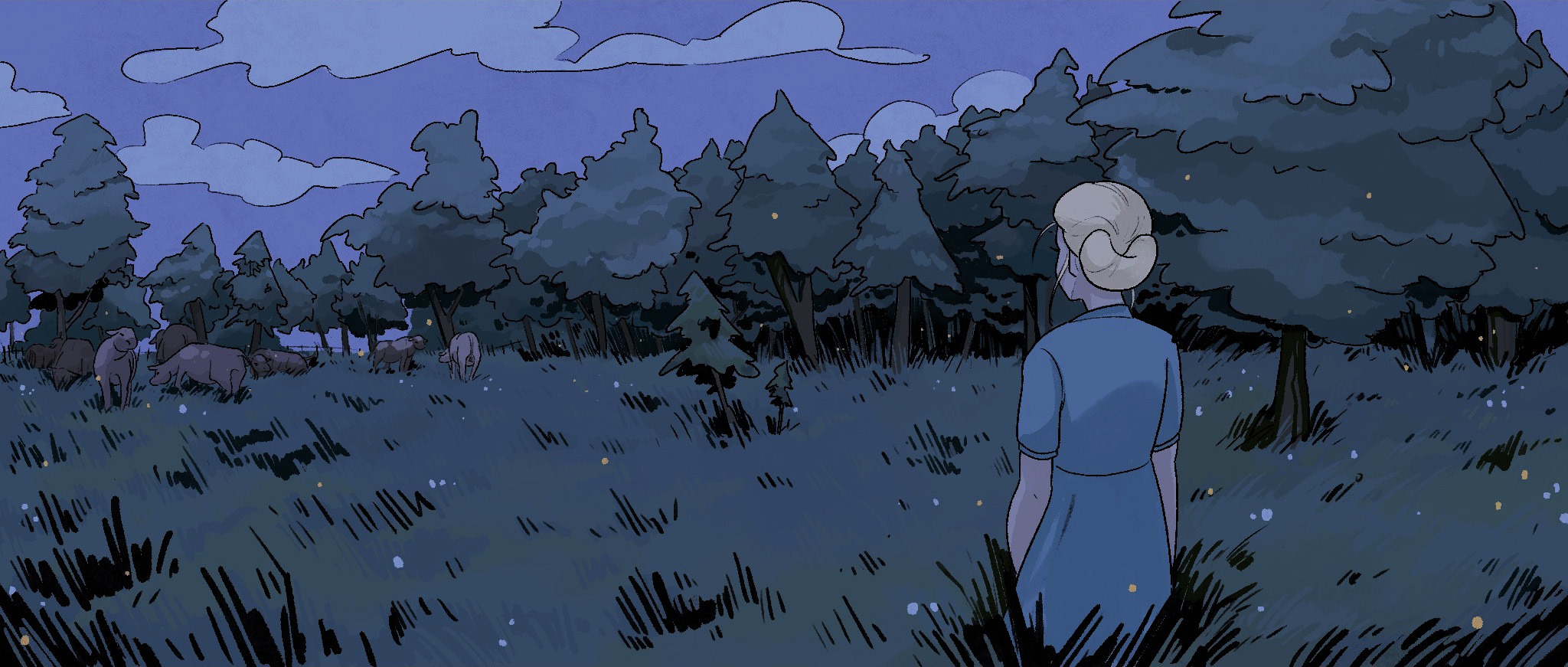

The dusk is clear and cool. The tall grass is dry and brushes against the fabric of her dress with a light whooshing sound. Insects spring up into the air around her, just visible in the growing darkness. Distantly, the cows are lowing their goodnights. Ahead of her, the wall of the forest rises into the sky, the flashing eyes of a passing animal winking from the gloom.

She turns.

Māmiņa is bustling towards her, the hems of her casual skirts bunched in each hand. Her round face is red from an afternoon spent toiling in the kitchen. Her graying hair floats around her face where it’s escaped her bun. Behind her, the family sheepdog watches dutifully from the porch, wagging his tail enthusiastically, unable to decide if he should follow.

“Dinner’s ready,” Māmiņa says when she reaches her.

“I know,” Luiza says. “You didn’t have to come all this way to tell me.”

Maybe the way she says it is rude. People tell her that – that the way she speaks is too blunt sometimes, or that she doesn’t always say the right thing at the right time.

Māmiņa doesn’t seem to think so. She laughs, because she understands that Luiza is trying to be considerate. “Yes, but you looked so peaceful out here I thought I would come see for myself!” She shivers. “It’s much colder out here, though. We’ll have to start preparing for the winter soon.”

Luiza falls into step beside her. She has no interest in the weather, so she doesn’t say anything. Māmiņa knows this and doesn’t wait for a response. “Māte is going into town tomorrow for a delivery. She says you’re welcome to go with her if you want.”

Luiza nods. “I’ll go,” she says. Māte can handle herself, but Luiza likes to make sure. It’s been a long time since she was under any delusions regarding how the people in town view her family, and there’s always the chance that one of them gets too confident if they spot one of her mothers alone.

Māmiņa smiles. “I knew you’d say that! It’s good for you to get out every once in a while. I know it can be a little overwhelming sometimes, but you have to admit there are interesting things to see.”

Luiza can’t disagree with her. For as much comfort as Luiza finds in her routine, she also yearns to be the type of person who enjoys adventure. (Wanting to be that kind of person and being that person are awfully close to the same thing, she thinks. She imagines making the jump is just a matter of time.)

They make it back to the house. The dog wags his tail and follows them inside.

It’s warm in the kitchen. The room is flooded with yellow light. The tablecloth is a nice texture, elegantly embroidered with summer flowers. The rich smell of the stew Māmiņa had been cooking reminds Luiza that she hasn’t eaten since that morning, and she joins Māte and Mama at the table. The dog settles eagerly at her feet.

Luiza remembers the rest too: the way her spoon reflected Mama’s face when she was asking about Luiza’s day. The gradual procession of darkness arriving in full outside as Māte hashed out the plan to wake up early in the morning. The pleasant buzz of the electric lights overhead as Māmiņa leaned over to clear her empty bowl, kissing Luiza on the crown of her head as she did. Luiza remembers helping with the dishes and saying goodnight and taking the dog with her to bed, all of it so vivid that, for a moment, she allows herself to indulge in the fantasy of it being real.

The dream parts slowly like the curtain at the town’s theater, and Luiza opens her eyes on the still-dark of her bedroom in Valhalla.

It’s fashioned to take after her bedroom in the farmhouse. It’s not something she finds comforting, just then.

She rolls out of bed (the one with no dog) and into her slippers, and she marches decisively out of her room.

The hall is dimly lit, but the lights brighten gradually as she crosses to Angora’s door. She knocks twice, wincing internally at how loud it sounds in her ears.

A minute later, the door opens (are hinges supposed to be that loud?), and Angora appears, rubbing sleep from her eye.

“Luiza?” she wonders, still waking up. “What’s wrong?”

“Vai es varu palikt?” she blurts, and she doesn’t mean to say it in Latvian, but she’s still somewhere halfway between the past and the present and the words are out of her mouth before she has time to think about it.

Angora takes a second to translate, mouthing the words to herself until understanding dawns on her face. Her expression shifts to something more serious and she lets Luiza in, and only once the door closes behind her does she say, “Tu raudi.”

Luiza had forgotten that. “I’m sorry,” she says, reaching up to wipe at the wetness on her face.

“What? No, no,” Angora soothes her. “I’m just worried. Did something happen?”

Luiza feels a little silly, talking about it out loud. “A dream. I just… didn’t want to sleep alone.”

Angora’s face softens. She takes Luiza’s hand slowly and leads the way over to her own bed, the same as Luiza’s but decorated with scratchy old throws and a colorful patchwork quilt.

She removes the blankets she knows Luiza can’t stand to touch and sits her down on the left side of the bed, crawling onto her own side and switching off the light. In the dark, Luiza feels a bit braver, and she lays down, pulling the quilt up to her chin.

The smell is nice. It’s nothing like home, so it’s nice.

“Do you wanna talk about it?” Angora’s voice cuts into the silence after a moment.

Luiza thinks she should. It might honor them, to be remembered aloud forever, like a daina passed between generations. (Except there are no generations in Valhalla – only immortals, burdened with the remembering until the end of time.)

She’s not sure she can find the words though, so she settles for, “I dreamed of my mothers,” and allows the I miss them to hang heavy and unsaid in the air between them.

Angora rests a calloused hand over Luiza’s bicep and shifts closer. Luiza follows the pull on her arm until her face is tucked into Angora’s clavicle, the top of her head fitting just under Angora’s chin. Angora smells like her blankets (or, more likely, they smell like her), and that’s nice too.

Luiza doesn’t have the energy to tell her the full story just then. It would feel strange, trying to impart the memory in a room defined by things so foreign. Maybe tomorrow, or later that week. The next time they’re hanging out in Luiza’s room, perhaps, and she can try to show Angora what it was like to be her, back then.

But Angora doesn’t demand anything, and she’s happy to let Luiza stay. She runs her fingers through Luiza’s unwound hair until the two of them drop off into sleep, and for the moment the sharp scent of cinnamon and clove is enough to keep Luiza’s dreams rooted in the present.