#asian american studies

I just got the news that a newlywed couple in our community were the target of hate crime. The guy has a broke nose, among other injuries, and the wife is in the ER and needed to get stitches on all of her face. They were merely were out to walk around the neighborhood and this happened to them within the comfort of their neighborhood.

These sort of hate crimes happen all the time, not too long ago, and old man was selling shoes/other little things in front of his house and was beaten up by 3-4 young men. In front of his house. On his porch.

I want to stress that these both cases (among others) weren’t carried out anyone other than the precious ~PoCs~. This is exactly what I mean when I talk about hierarchies, because in people’s little perfect theoretical worlds, everything is created into simple categories, where the Pakistanis/Asians have privilege and can’t be target of hate crime/racism when carried out by Black or Latin@ people because of the apparent political power we hold.

These hierarchies are created by White supremacist thought, and as long as we don’t move away from them, and go on about false sense of power dynamics (in which everything is depicted as one sided) we will not get to the root of the problem.

When people speak on Asian or Pakistani privilege they are completely removed from the reality we live in, and want a simple cookie-cutter theory when in fact reality is much more complicated than that.

I know this is supposed to be “controversial” because I’m going against whatever is held to be the truth on here, that Pakistanis/Asians hold certain power over Latin@ or Black communities and that whatever crime done against us, the constant spying, living under the security/surveillance apparatus is a mere form of “prejudice” without any sort of power behind it, the anti-islamic and anti-pakistani hate crimes exist in some sort of tight limited space of “privilege” but that’s not the reality many of us live in and I would rather not follow some removed-from-reality theory for others convenience.

Of course, I shouldn’t have to stress this as it’s obvious, that I don’t mean if X doesn’t have power than Y obviously does. But this is to complicate the simplistic approach to race most people have where the hate crimes carried out by people who fall into the PoC category get unchecked and unnoticed. White crimes on PoC exists in various forms, but that’s not the start and end of the conversation and racial dynamic.

Simply put, these hierarchic sand faux “privilege” politics distort reality.

Title: “SEA Legacies: Commemorating 40 Years of Southeast Asian Diasporas”

The goals of the symposium are to commemorate the formation of Southeast Asian diasporic communities in the US over the past 40 years and to educate students and the community about Southeast Asian American heritages, experiences, and histories.

Events in no particular order:

A. Keynote: Dr. Viet Nguyen, Departments of English and American Studies and Ethnicity, USC

B. Panel: Vietnamese American Authors: Telling Diasporic Stories from Vietnam to the US

C. Panel: Southeast Asian Experiences

D. Panel: The Fall of Saigon: Political Background and Military Context

E. Roundtable: Alumni Experiences: Intergenerational Dialogue

F. Panel: CBOs & JOBs: Get to Know Local Community Organizations and Resources

G. Roundtable: Let’s Get Engaged! Students Share Opportunities for Campus and Community Involvement and Service.)

H. Panel: Preserving and Sharing Our Stories: The Role of Southeast Asian Oral History Projects and Archives

I. Digital Photo Exhibit: Vietnamese Americans: A Self-Portrait of a People

J. Exhibit: Letters from Vietnam

K. Film Series: Visual Stories of Diaspora: An Exploration of Southeast Asian History and Life through Films

L. Panel: Beyond the Fall of Saigon: Communism as Discourse in National, Community, and Identity Formations in the US and Vietnam

M. Panel: Global Perspectives on the Vietnam War

N. Panel: National Resource Center for Asian Languages and Vietnamese Literacy Development for Dual Language Immersion

O. Closing Performances: Southeast Asian American Expression and Performance

The SEA Legacies Symposium is generously sponsored by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences and by Dr. Craig K. Ihara.

The SEA Legacies Symposium is organized by faculty, students, and staff of Asian American Studies, Modern Languages and Literatures, History, American Studies, Political Science, Psychology, Sociology, Communications, Education, the HSS Office of Development, the CSUF Office of State and Community Relations, the Vietnamese Students Association, the Cambodian Students Association, and the Asian Pacific American Resource Center, and in collaboration with community partners.

Please contact Dr. Eliza Noh at [email protected] for more information.

Please don’t forget to share the eventbrite RSVP link with the campus and external community. All attendees, including speakers and yourselves, should register by Feb. 20th so that we can take a headcount for food:

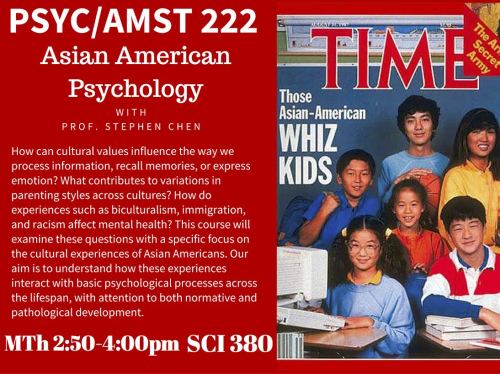

Interested in understanding Asian-America through a psychological lens?! Or perhaps passionate about mental health issues as they manifest in communities of color?! Register for:

PSYC/AMST 222: Asian American Psychology

Post link

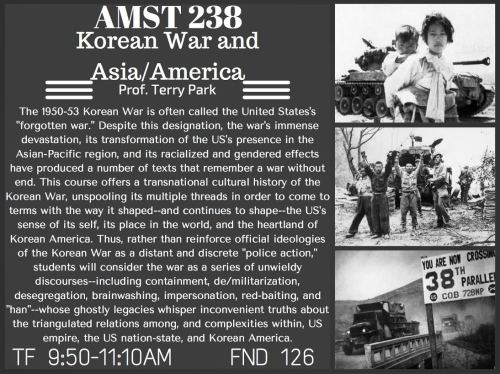

WELLESLEY FRIENDS! Still looking around for a last class?! Interested in AA Activism, Ethnic Studies, or the consequences of U.S. Imperialism?! Register for

AMST 238: Forgotten/Remembered–The Korean War and Asian/America

taught by *new hire in the American Studies Dept, Terry Park!*

(who also served as a former Executive Director of Hyphen magazine!!!)

Post link

In the summer of 2001, between my 3rd and 4th year at UC Irvine, I was spending a couple of weeks in San Francisco, regrouping after a tumultuous year. I was still fresh off of failing miserably at electrical engineering, and I looked for alternatives to dropping out altogether, I found myself making an initial foray into Asian American Studies. Admittedly, I assumed it would all be a piece of cake (as my parents later put it, “You’re Asian, what else do you need to know?”), but a couple classes in I realized I knew almost nothing. Manila Men. Chinese Exclusion Act. Gentleman’s Agreement. Internment. Larry Itliong. I-Hotel. Vincent Chin. Yuri Kochiyama.

I don’t remember exactly what it was, but for some reason I latched onto Yuri’s story almost immediately. Maybe it was pride in the fact that she was out there fighting the good fight during a time when it seemed like Asian Americans were largely invisible. Or maybe it was the fact that she was STILL fighting injustice in all its forms. I couldn’t find a whole lot of reference material on her at the time, but whatever I could find I printed out/xeroxed/purchased. I even sought out bootleg copies of Renee Tajima-Peña’s seminal documentary My America. It wasn’t long before her visage replaced the anime wallpapers I had previously on my computer desktop. She had become my hero.

So there I was, hiding out in the Bay Area, pretending to be up there for purely academic reasons (I took Oliver Wang’s Asian Am Film class to justify my not going home that summer), but really just experiencing everything I had just begun to learn about. I went to the empty space where the I-Hotel once stood, gazed mournfully across the Bay at Angel Island, and inadvertently ended up at the first Asian American Spoken Word and Poetry Summit in Seattle. But all of that paled in comparison to the day I met Yuri.

I had tagged along with my friends to Dolores Park to participate in a Free Mumia march, a 6-mile roundabout trek from the Mission to the Civic Center. As we sweated it out under the hot San Francisco sun, waiting for things to get going, one of my friends who had been wandering around came back and said “Yuri’s here.” The way he said it was so casual, so matter-of-fact, as though she was just another one of the regulars at these gatherings. And whether or not that was true, I could barely contain the emotions I felt just knowing she was there.

Of course I had to meet her, and after darting about the crowd for a couple minutes, there she was. She was in a wheelchair and battling the heat herself under a large umbrella, but still looking cheerful, like she was getting ready for a pleasant walk in the park. I stood a couple feet away, tentative, not sure whether or not I was even allowed to approach her. These days, I have friends that knew Yuri personally and would probably laugh at this, but back then, I felt like I wasn’t worthy to be in her presence.

So at first I end up making a little small talk with who I think was her grandson. And then, in the most sheepish voice possible, I turned to her and said “uh…. Hi!”

And while I would rather not transcribe the awkward conversation that followed, there was one thing she said that I would never forget:

“Thank you.”

I was puzzled. What was she saying “thank you” for? In the blur of pleasantries and fanboyisms I had probably been sputtering out, I wasn’t quite sure what had elicited her gratitude.

“Thank you for coming today.”

And then, I understood. She was grateful that I was there at the march, that my friends and I had taken time out to support a cause that she truly believed in. At first I felt embarrassed: I should be thanking her just for even speaking with me, which I did. But it wasn’t because I had awkwardly gushed over her and her significance, she was really just happy to see us there.

There were a lot of other things that happened that day, that summer, that year that really affected my perspective, but that brief encounter with Yuri was one of the most memorable. And while I wish I could wrap up this whole story with a neat cliché about how that conversation led to some greater epiphany, it didn’t. I was just happy to have met her, especially in that place on that day. And since then, whenever I start a new job, the first thing I do once I get settled in is replace the crummy wallpaper on my computer with a picture of her. Partly to remind me of the struggles that were fought and that still need to be fought so that I could even sit at this desk. But mostly to remind me to be grateful.

Michael Nailat is a Program Officer at the United Way of Greater Los Angeles.

Back when I was in college, we were all buzzed that Yuri and Bill Kochiyama came to us, giving strength to our cause in getting an Asian American studies class on campus and on forming an Asian group whose sole purpose wasn’t just to throw parties. They had both just come back fresh from testifying to Congress about Japanese American redress and it was mind-blowing to learn about the internment first-hand. Yuri and Bill always had time for young people, in their home and in their hearts. Later, when I was trying to write a profile about Yuri for a Hawaiian newspaper, I was a little frustrated because she refused to talk about herself, her individual experience. She would talk about people and movements and the inevitable triumph of justice. Rarely would she reflect on the young woman who went by “Mary” and how that young woman grew up to move mountains. A few years after that, I had the sad duty to write about Bill’s life when he passed away. I remember the ceremony and the gathering of people from all backgrounds coming together to celebrate the man. Now two decades later, Yuri and Bill are back together. Some people will point out Yuri’s strengths. But I will always remember her one adorable weakness. She and Bill kept a room full of teddy bears. She loved them.

Ed Lin is a New York-based writer.

This past spring, I wrote about Yuri Kochiyama for my senior honors thesis through the American Studies department at the University of California, Berkeley. I decided to write about the political activism of Yuri Kochiyama as an effort to challenge the Black-White racial paradigm that pervades the American mentality. I believe that by discussing stories of solidarity among ethnic minorities, we begin to understand the power of cross-racial collaboration and resist the racial categorization and separation enforced by white supremacy. Although I never met Yuri, I felt inspired and encouraged as I listened to interviews, watched documentaries, and read countless accounts of her brave, passionate work with underrepresented communities of color throughout her life. For this blog entry, I would like to share a portion of my thesis, which articulates her passion, hard work, and dedication to her community and the Black liberation movement:

“In the heat of the nationwide turn towards revolutionary politics and radical activism, Yuri Kochiyama developed her role as a “centerwoman,” an activist who is not a highly visible traditional leader like a spokeswoman, but nonetheless an important leader doing necessary “behind-the-scenes” work and providing stability to a social movement. A centerwoman directs her energy and passion for social change towards bringing people together, creating social awareness through personal conversations, and transmitting information through wide social networks. Kochiyama was able to embrace her role as a centerwoman in the Black community by joining or becoming an ally of many newly founded Black liberation organizations. Malcolm X’s death was a tragedy and an immeasurable loss to humanity. People across the globe were angry, saddened, and devastated. However, Black activists were also inspired by his legacy and founded Black nationalist, liberationist groups such as the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BART/S), and the Republic of New Africa (RNA). From her involvement with these organizations, Kochiyama was able to develop deeper and wider connections with more members of the Black struggle. Kochiyama, who knew countless people, from famous Black leaders to friends of friends, became the human equivalent of a social encyclopedia. One RNA activist recalled:

“Yuri used to waitress at Thomford’s. That became like our meeting place. Everybody would come in and talk to Yuri. So when you come in, Yuri would have the most recent information for you. If we wanted to set up a meeting, she would set it up. If you had a message for someone, you’d just leave it with Yuri She must have received fifteen, twenty messages a day.”

Kochiyama had a wide reputation for being reliable and active in the movement. Whether she was writing articles for movement publications, attending protests and demonstrations, or handing out leaflets for organizations, people knew they could depend on Kochiyama to acquire or disseminate important information. Kochiyama even held open houses on Friday and Saturday nights at her home where activists could congregate and discuss revolutionary ideas directly among themselves. Since the 1950’s, Kochiyama had always opened her home to friends and strangers alike who needed a place to stay. From famous activists like SNCC and BPP leader Stokely Carmichael, poet and BART/S founder Amiri Baraka, and OAAU leader Ella Collins, to small children, guests from different backgrounds and perspectives felt her hospitality, generosity, and kindness in her oftentimes crowded, but nonetheless welcoming home.[i]”

[i] Diane Fujino. “Grassroots Leadership and Afro-Asian Solidarities: Yuri Kochiyama’s Humanizing Radicalism.” In Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 300-304

Hannah Hohle is a recent graduate from the University of California Berkeley and is now pursuing her career as an educator through the Urban Teacher Center in Washington, DC.