#wellesley

Shout out to Allure for their tutorial on

Cultural Appropriation (i.e. teaching white girls how they too can make their hair into an afro). Here’s to the authentic Afro ✊ To quote the incomparable Amandla Stenberg, “Don’t Cash Crop on My Cornrows”

Post link

Seven sisters? Try fourteen as we celebrate at our Wellesley sister’s wedding. The sisterhood runs long, strong and deep

Post link

Classes coming this fall at Wellesley College’s new Department of Boss Studies.

BOSS 101 Doing the Damn Thing

BOSS 302 The Wellesley Effect Personified

BOSS 405 Glass Shattering

From the new series on Fiction Advocate–

How I Got Here: You Learn, I Pay

Privilege is a topic that doesn’t always receive the subjectivity and nuance it deserves. In “How I Got Here,” writers reflect on their experience of privilege (or lack thereof) in their writing careers. We hope these personal essays will help us appreciate the complexities of individual experience and view each other in a clearer light.

An MFA is a shot in the dark. It is a degree that costs thousands and thousands of dollars to pursue and yet has absolutely zero (0) guarantee of any type of employment. You get an MFA out of sheer love or delusion. When I applied to writing programs in the fall of 2011, I did so simply because I knew I loved writing and wanted to get better at it. I also applied because I had, and have had for my entire life, my own personal patrons of the arts.

There have been many calls lately for writers and artists to be more transparent about their financial situations, from the Twitter hashtag #PublishingPaidMetoessay collectionstothis very series. I remember when I first read Ann Bauer’s essay on Salon about how her heart surgeon husband “sponsors” her writing career and how much I appreciated her honesty. So, let me lay it all out there for you. When it comes to education, the rule in my family is: they pay, no questions asked. It’s like that scene in The Sopranos, when Meadow’s boyfriend tries to pay for Tony’s dinner and Tony is pissed. But instead of “You eat, I pay,” it’s: “You learn, I pay.”

Education has always been a big deal in my family. Both of my parents have Master’s degrees, my mother’s specifically in Music Education, which she used as a piano teacher. Both of my grandmothers achieved higher ed degrees at a time when it wasn’t common for women to even complete high school. My paternal grandfather nearly completed a PhD from MIT in engineering (everything but the dissertation); my maternal grandfather dropped out of law school, but he did so to take over a local driving school because he loved to teach kids how to use cars. Classes, studying, learning, teaching, books—I was taught that these were the most valuable types of currency. I knew from a very young age that there were limits to what I was allowed to ask for in a toy store or a clothing boutique, but the local bookstore? The word “no” did not exist there. In middle school, I memorized my dad’s credit card number so I could order books on the Barnes & Noble website without bothering him (so advanced for 1998!), and he never questioned what I was buying, as long as it was books. He also never questioned how much I was buying because he had access to that other, more literal type of currency—money.

Read the rest of the essay on Fiction Advocate.

Interview by Cleo Hereford ‘09

A Delaware native and member of the Nanticoke tribe, Courtney Streett ‘09 is currently the President and Executive Director of the Native Roots Farm Foundation (NRFF). NRFF is a non-profit organization “dedicated to celebrating Native American cultures, protecting open space, cultivating a public garden, and practicing sustainable agriculture.” Prior to founding NRFF, Courtney was previously an associate producer at CBS News working on both the CBS Evening Newsand60 Minutes and was also a senior news producer for the Business Insider.

I was super excited to catch up with my friend and classmate about her exciting new work with the NRFF.

Cleo: Thanks for chatting with me, Courtney! Before we talk specifically about the Native Roots Farm Foundation, you say NRFF’s story starts with your great-grandparents. Tell us a little bit about them and also your family’s Delaware roots.

Courtney: Thanks, Cleo, for inviting me to share my journey with the Wellesley Underground community!

My family has been in Delaware…since time immemorial. Through my father, I’m a member of the Nanticoke Indian Association and our family tree goes back several hundred years in lower Delaware (since European records were taken). The Nanticokes’ first contact with Europeans was in 1608 with Captain John Smith, yup, the man who kidnapped Pocahontas. The community has survived since then by assimilating into the mainstream, but many aspects of our culture were lost. That includes our relationships with food and nature – rather than seasonally moving between fishing, hunting/foraging, and growing regionally adapted crops, the Nanticoke had to adjust to the European practices of private land ownership and farming in one place year round.

At the turn of the 20th century, my Nanticoke great-grandparents bought a farm. It was unusual for people of color to own property at that time, but they cultivated the land and sold produce like strawberries, raspberries, peas, and tomatoes to passersby at the beach. Through hard work, dedication, and tenacity that property passed down through generations of my family and is now owned by my father’s cousins. I grew up visiting the farm and it’s provided a connection to both the natural world and to my ancestors.

Cleo: Native American communities, like all minoritized communities, are not monolithic. What would you like WU readers to know about the Nanticoke, the tribe that your great-grandparents were members of?

Courtney: We can thank Hollywood for creating the stereotype that all Native American communities live on reservations, have long straight hair, have tepees, and operate casinos.

Indigenous communities have been largely erased from American history – today Pennsylvania doesn’t even recognize any tribal communities. But we know the Lenape, Susquehanna, and Iroquois were some of the area’s first inhabitants.

We are still here! The Nanticoke have a Powwow every September that’s open to the public. Mark your calendar: September 10 and 11, 2022! It’s a celebration of our culture and community and an affirmation of our roots in Delaware.

Cleo: Let’s talk about NRFF. You previously worked as a producer for CBS News and the Business Insider. What made you take the leap into establishing a non-profit organization? Why focus on a public garden and farm?

Courtney: I was living in Brooklyn and working my dream job; and then my dream changed.

After Powwow in 2018, I saw that the farm my great-grandparents had nurtured was for sale. I knew this cultural and agricultural history couldn’t be lost – and I also knew that my partner and I couldn’t afford to buy 100 acres, 10 minutes from the beach.

I had nightmares about the farm disappearing. Because in this area, the crops have been replaced by condos. Lower Delaware has been one of the fastest developing regions of the country. After months of conversations and research, we realized our limitations as individuals, but that as a collective, we could make a difference. So, we created Native Roots Farm Foundation (NRFF).

Why plants? When creating NRFF, we wanted to celebrate Indigenous communities, the farm’s agricultural history, and also native plants. So, NRFF has a few different components to its mission. We’re working to celebrate local Indigneous communities by protecting open space, creating a public garden with native plants and highlighting what they’re called by the Nanticoke and Lenape, and cultivating a farm that feeds the community using Indigenous agricultural techniques.

I also love plants and getting my hands in the soil – I did research in the Wellesley’s Greenhouses my junior year and presented at the Ruhlman Conference. I didn’t know how that would manifest in my life, but it was a building block for NRFF. Sibs, while on campus (as students or alums) check out the new greenhouse, explore the edible ecosystem, and walk one of the many beautiful trails! You never know how it’ll change your life!

Cleo: Building an organization in the best of times is not easy. How has it been attempting to establish and grow NRFF during the ongoing (never ending) pandemic?

Courtney: Hahaha what an interesting question. We launched NRFF in January 2020…and the rest is history. Lockdown meant we had the time to sit on the computer, file paperwork, and really build a strong foundation for NRFF.

It also meant that events we had planned couldn’t happen. So, we pivoted and started building an online community which has continued to grow and flourish during this never ending pandemic. Every week, we post on social media about native plants, food systems, and Indigenous communities.

(Shameless plug—follow us on InstagramandFacebook!)

Cleo: In addition to protecting land at risk of development, how does climate change factor into your goals for establishing NRFF?

Courtney: Right now, the buzz words in food production are “regenerative agriculture”. Regenerative agriculture is *Indigenous Agriculture*. But, of course, the Indigenous roots of this land stewardship practice are rarely recognized. Instead, regenerative agriculture is celebrated as a brand new way to farm.

Why are we hearing about this now? Most food is grown using industrial agricultural practices that have been linked to pollution, soil erosion, intensive water use, reduced biodiversity, chronic illness, and greenhouse gas emissions which are causing climate change.

Regenerative agriculture differs because it’s a holistic approach to land management. It recognizes the interconnectedness of soil, plants, water, animals, and people without centering humans. In practice, regenerative agriculture focuses on nurturing soil health, because that determines the health of both people and the planet.

Most importantly, regenerative agriculture is about community and equity – principles and approaches NRFF celebrates. Let’s get back to the roots and work with nature to address climate change.

Cleo: In addition to posting about sustainable farming and plant life, you have also posted about rejecting blood quantum and have highlighted those with both Black and Native ancestry on the Native Roots IG page. As someone who is both Black and Native, why has it been important for you to post about those topics?

Courtney: My mother’s parents were from the Caribbean and I always saw my two cultures, Indigenous and Caribbean, as being separate. With mom you eat flying fish and callaloo. With dad you eat fry bread and succotash.

But then I heard a song that stopped me. It was “Ba Na Na” a blend of Caribbean beats and Native drumming (by the Indiegnous group The Halluci Nation). The lyrics are: “…Carnival season, this life for the books/I jump and I wave and I wine and I juke…” Just like this song mixes genres, I can and other people can, too. It’s time for all of us to embrace our full cultures and identities.

Cleo: What are your long and short-term plans for NRFF? Where do you see the organization in 5 years?

Courtney: In five years, I see NRFF welcoming the Wellesley family to its fully operational public garden and sustainable farm!

More immediately, we have our first big event of 2022 next weekend and I’m looking forward to continuing to build community, making Tehim Juice which has become an NRFF staple (Tehim is Nanticoke for strawberry), and meeting new people! We’re also hoping to have an intern this summer and just submitted a Hive Internship Project.

Cleo: Finally, how can your Wellesley sibs and WU readers support you and your organization?

We’re still a new organization, in the startup phase, and I’m so grateful for the support of the Wellesley family!

You can help uplift NRFF’s message by following us on social media, sharing the organization with your community, grabbing our signature shirt that says “This shirt saves farms”, or making a donation.

But don’t stop with NRFF, get to know your native plants! Plant them in your yard, window box, or planter. Learn what they’re called in the Indigenous language where you live. And foster a love for your local ecology.

____

For more information on NRFF or to support the organization: https://www.nativerootsde.org

You can also follow NRFF on Instagram@nativeroots_de

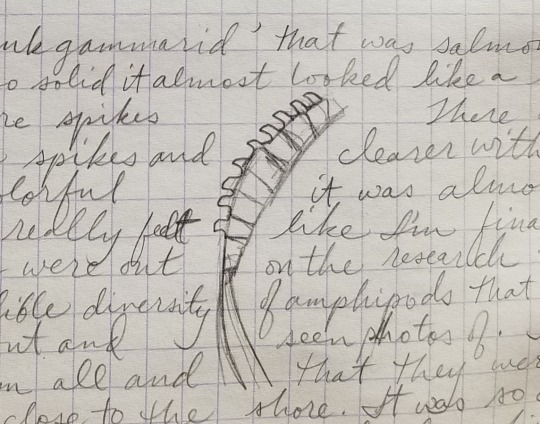

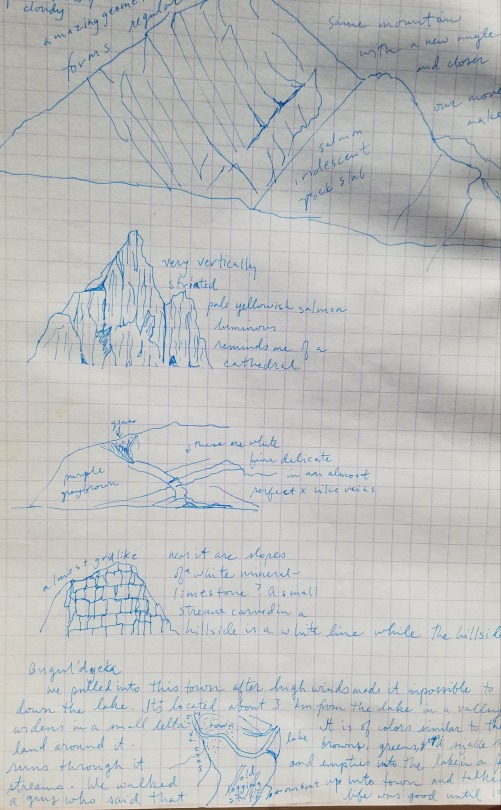

In early August 2001, I set down my bag in a simple dormitory in the village of Bol’shie Koty on the coast of Siberia’s Lake Baikal. “We each get a bed, cupboard, and closet space, and there’s a cool Russian stove. Our room overlooks the lake!” I enthused in my journal. Bol’shie Koty, whose 150 summer residents dwindle to only 80 in the deep Siberian winter, is, like many communities along the nearly 400-mile-long lake, accessible only by boat. The crescent-shaped lake is the world’s deepest (over a mile), the world’s oldest (at least 25 million years), and holds the most water of any lake (around 22% of the planet’s fresh surface water). Unique as well as superlative, Baikal hosts hundreds, if not thousands of animal species found nowhere else on earth, including sponges, fish, amphipods, and a freshwater seal. In remote southern Siberia, its watershed drains vast expanses of Mongolian steppe and Russian taiga, and the lake holds a somewhat mythical place in Russian culture. As part of the inaugural expedition of the Wellesley-Baikal program, which paired a spring course on Baikal history, literature, and ecology with summer study at the edge of the lake, I had rejoined my classmates after graduating from Wellesley and spending a summer in my home state of Vermont.

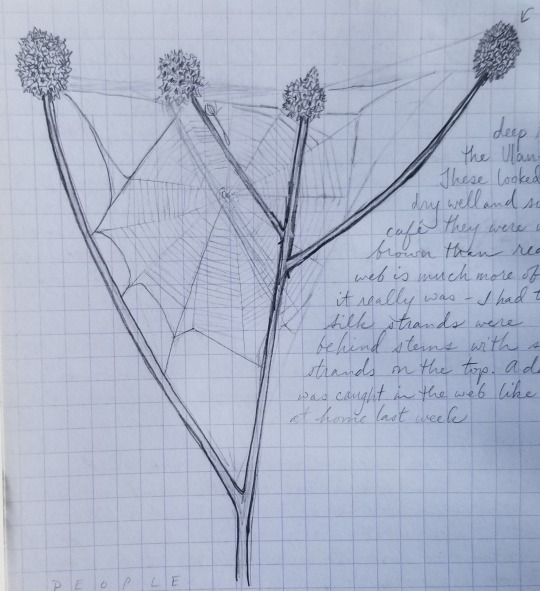

Over three weeks we explored the lake and its surrounding towns and forests, taking water samples and plant inventories and meeting local scientists, artists, land managers and even a shaman with a double thumbnail. On that gravelly shoreline, while also at the figurative shore where college meets adulthood, I was enchanted by the ways this place burst with both novelty and familiarity, and I immersed myself in observation to make connections between them.

On our misty boat ride to Bol’shie Koty, I saw eerie expanses of ghostly, bare tree trunks near the head of the Angara River, the bare, pointy stems resulting from an intense local outbreak of Siberian silk moth caterpillars. I was fresh from a field technician job counting invasive insects and inventorying disease in white pine stands for the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation, and diligently took photos for my boss back home.

A few days after, I observed a female Siberian silk moth, “a beautiful creamy shimmery color with delicate folds,” alight on our boat in the lake, whose water looked “almost glacial in its deep blue green, slightly milky texture.” As I watched from where my classmates and I were taking samples, “one moth took off from our boat and flew valiantly toward shore, only to come closer and closer to the water until finally landing, becoming a creamy speck on the blue-green Baikal waters.” Later, I felt an odd surge of recognition - as well as horror - when one of us turned back a bedspread (“of a smooth cotton and muted brown/blue/purple/pale pink weave”) to find the grayish, fibrous lump of a silk moth cocoon. The caterpillars of Dendrolimus superans sibiricus defoliate Siberia’s characteristic coniferous forests, devouring needles of tamarack, pine, spruce, and fir.

Twenty years later, I’m back in Vermont, reading these somewhat overwrought - and repetitive! - words of my younger self while the larvae of Lymantria dispar (their common name, ‘gypsy moth’, is a derogatory ethnic slur) devastate trees around me during one of the worst outbreaks in Vermont in 30 years. Lymantria dispar larvae, like their distant Siberian cousins, feed on trees that distinguish Vermont’s forested landscape, though they defoliate oaks and other hardwood trees rather than the needle-leaved conifers that the Siberian caterpillars eat. I work as an ecologist and spend much of my time on projects that protect another huge lake, Lake Champlain, and its watersheds. I still love Russian literature, saunas, and dill, my appreciation for all of which sharpened during my time at Baikal. The world changed forever just three weeks after we returned from the far side of it that year. Yet in my own life, throughlines from those days along the crumbling shoreline continue to surface and reverberate in the present. Like the fine threads of a Siberian silk moth cocoon, these connect my past and present selves, shaping and in turn being shaped by perspectives and decisions that continue to unfold.

I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, but on rereading my excruciatingly detailed journal, I can see that this trip to Russia was the first time that I, at age 21, saw myself as a witness to and participant in the churning path of history, rather than merely a visitor to museums and ruins clearly separating past and present. Opposing truths can exist at the same time, the past continually bumps up against the present, and these moments and impressions form part of an unfolding and messy whole.

I marveled at juxtapositions. The beauty of the silk moths and the devastation of the forests in their wake. Wild-looking river deltas along the lake, thick with larch and cobble, that were in fact just decades out from the ecological and human devastation of slave-powered gold mining and deforestation. The expanse of lake viewed from an old rayon factory in Baikalsk, where I pondered a failed Soviet scheme to make airplane tires from wood pulp. A wolf wandered the shoreline and lynx pelts adorned the walls of a village home. Cows wandered the lanes and wooded margins of Bol’shie Koty, while rough fences kept livestock out of yards instead of in pastures, where they would have been in my familiar Vermont. Yet this surprising settlement pattern recalled early New England villages modeled after those in England, where overgrazing of common areas inspired the ecological and economic concept of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ in the mid-nineteenth century.

In Russia I saw academic concepts like this embodied in the land and lives around me, and the contrasts activated my thinking. Primed by the wide-ranging spring course with Tom Hodge and Marianne Moore, big thinkers with endlessly curious minds, I filled my journal with lists of plants, records of weather, notes from lectures and questions to consider.

One day our group got to witness the value of a long-term journal first hand. Talking with biologist Lyubov Izmesteva, in her dusty lab, we learned that her grandfather, Mikhail Kozhov, had begun recording ecological data on the lake in 1945, offshore from Bol’shie Koty. He passed the pen to his daughter and now granddaughter, and their collective decades of observation yielded a unique record of the lake’s health. Marianne Moore recognized the value of this careful record in 2001 and has shared it more broadly in the years since that trip. Reaching through and beyond the Soviet era, this family project is now helping the rest of the world understand how climate change is impacting Baikal.

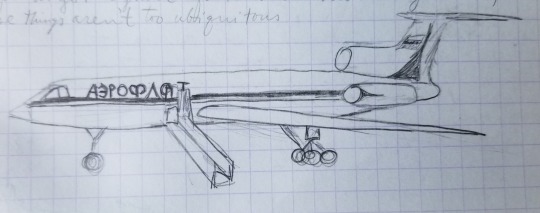

Though I lacked a deep grounding in Russian political history, I felt a momentum in Russia, which seemed like it was still actively turning a corner from the drudgery and oppression of the Soviet era toward the complexities of democracy and capitalism. I knew the forested hills, river valleys, and watery depths around me held painful histories, like the cut-short lives of “uncounted, unregistered hundreds [of political hostages], unidentified even by a roll call” deliberately drowned in Baikal around 1920 as part of Russia’s post-revolutionary, pre-Stalinist horrors, and described by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago. In Moscow in 2001, I snapped a photo of a billboard advertising chewing gum, looming over a Soviet-era statue. The frivolity of the gum, its promise of a tiny personal diversion, seemed to contrast in a fascinating way with the stern Communist officer on his horse, frozen in metal.

In Moscow, I wrote, “Miles & miles from the city center are 6-lane streets, long apartment buildings, stores (many for furniture/home furnishings), people strolling, hurrying or waiting, painting, digging, talking, rolling out sod, carrying wallpaper, buying clothes, selling watermelons, riding bikes, doing exercises, kissing”. The pendulum seemed to be swinging toward growth and expansion. Yet other pieces just hadn’t caught up yet. I remember a car pulling another car on a busy city street with only a thick piece of rough twine, goldenrods and tall grasses adding a surprising wildness to the edges of city sidewalks, the shopkeeper in Bol’shie Koty calculating change with an abacus. I observed these dynamics with curiosity and delight.

In 2021, Baikal is an Instagram backdrop and Russia, presided over by a former KGB officer, a shaky mix of democracy and authoritarianism. I haven’t been back, but I wonder if the residents of that busy Moscow street still feel the forward-looking momentum I observed. Are they still carrying wallpaper and rolling out sod, shaping their spaces? As influencers filter images for fantastic effect and shadows of the Soviet era continue to loom, I can’t find the photos I took with film on that trip, or the paper (the last of my college career) that I wrote by hand on the porch at Bol’shie Koty. I still keep methodical notes about land for my job, but my personal journal these days contains mostly scattered thoughts on parenting, relationships, and career, quotes from podcasts, and conceptual brainstorms. I write in it to get ideas out of my head and process the complex dynamics of life, not to record anything for posterity. But in reflecting on Baikal two decades later, I realize my younger self gave me a gift in the form of her obsessively detailed notebook. She helped me decipher the throughlines that connect me to her, through a trip we both took to the other side of the world. My work now is to figure out how to pay this gift forward, to whatever selves come next.

Juneteenth is nearly upon us and WU encourages all of our fellow non-Black alums to truly think about what the day means to our Black siblings. Further, it is important for allies and accomplices to keep the perspective that, while some may feel it important that Juneteenth be recognized as a national holiday, there is the very real possibility that the day could become commercialized or whitewashed in a way that is not beneficial to the Black community. And that while the day may be formally recognized, voting rights in states where there are significant black populations are being stripped away, abortion rights are being threatened, police brutality is still a thing and there is an ongoing discussion (war) on Critical Race Theory in US public schools and institutions.

While you contemplate that, WU also encourages you to financially support, if possible, organizations focused on Black women as well as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Donating to Wellesley is great but HBCUs in particular often have much smaller endowments and resource pools than PWIs (and sometimes are deprived of money that is rightfully owed to them). We have put together a list of organizations and HBCUs for you to consider supporting on this Juneteenth:

ORGANIZATIONS

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective

Black Women’s Health Imperative

National Black Women’s Justice Institute

Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI)

Southerners on New Ground (SONG)

The Foundation for Black Women’s Wellness

HBCUs

Alabama A&M(Alabama)

Alcorn State University(Mississippi)

Bennett College(women’s college; North Carolina)

Bowie State University(Maryland)

Clark Atlanta University(Georgia)

Dillard University(Louisiana)

Fisk University(Tennessee)

Florida A&M (Florida)

Grambling State University (Louisiana)

Hampton University(Virginia)

Howard University(Washington, DC)

Jackson State University (Mississippi)

Kentucky State University(Kentucky)

Langston University(Oklahoma)

Lincoln University(Pennsylvania)

Meharry Medical College(Tennessee)

Mississippi Valley State University(Mississippi)

Morgan State University(Maryland)

Morehouse College(Georgia)

Norfolk State University(Virginia)

North Carolina A&T State University(North Carolina)

Prairie View A&M(Texas)

Savannah State University(Georgia)

Southern University(Louisiana)

South Carolina State University(South Carolina)

Spelman College(Georgia)

Tennessee State University(Tennessee)

Tuskegee University(Alabama)

Virginia State University(Virginia)

West Virginia State University(West Virginia)

Xavier University of Louisiana(Louisiana)

____

If museums and/or cultural organizations are more of interest, seethis listof Black/African American institutions we put together last year.

____

Cleo Hereford ‘09

OnTuesday, April 13th, the Class of 2009 is hosting the following talk which is open to all members of the Wellesley Community.

________________

From Abortion Care to Parenting: Supporting Folks throughout the Spectrum of Pregnancy

Date: Tuesday, April 13th

Time: 7pm EST

Register in advance here

Megan Aebi Opeña (she/her) is a Latina, mother, doula, and community activist. She trained as a community based doula while studying for her MPH at Boston University, became a member of the Doula Project in 2015, and eventually became a certified full-spectrum doula. Megan has supported over 50 families throughout the perinatal period and over 200 folks during abortions. She has delivered and designed trainings on full-spectrum doula work for over 500 doulas in 3 countries and 10 States, with an emphasis in anti-racism work. Her goal is to provide people with access to information and support.

She lives in Brooklyn, NY with her husband, toddler, bonus son, and dog Toast.

________________

Bring your questions!

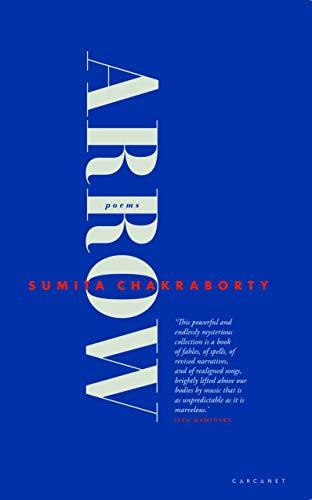

Sumita Chakraborty is a poet, essayist, scholar, and a graduate of Wellesley College, class of 2008. Her debut collection of poetry, Arrow, was released in September 2020 with Alice James Books in the United States and Carcanet Press in the United Kingdom, and has received coverage in The New York Times,NPR, and The Guardian. Her first scholarly book, tentatively titled Grave Dangers: Death, Ethics, and Poetics in the Anthropocene, is in progress. She is Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Poetry at the University of Michigan - Ann Arbor, where she teaches in literary studies and creative writing.

Sumita’s poetry appears or is forthcoming in POETRY, The American Poetry Review, Best American Poetry 2019, the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, and elsewhere. Her essays most recently appear in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Her scholarship appears or is forthcoming in Cultural Critique, Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment (ISLE), Modernism/modernity, College Literature, and elsewhere. Previously, she was Visiting Assistant Professor in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, as well as Lecturer in English and Creative Writing, at Emory University.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10, had the chance to chat with Sumita about publishing, reading, and writing. E.B. is grateful to Sumita for willing to be part of the Wellesley Writes It series in the middle of her book debut!

EB:Thank you so much for being part of the Wellesley Writes It series, Sumita! I’m excited to get to talk to you about writing in general, but especially your debut collection Arrow. Can you start off speaking a bit about how this book came about?

SC: Thank YOU so much! This is such a joy.

The book that’s now Arrow went through about seven prior full versions.

EB:Oh my gosh! Wow.

SC:While there’s a lot going on in there, the most fundamental story I wanted to tell was that of the experience of living in the aftermath of severe domestic violence, other entangled forms of assault, and grief (in my case, particularly for my sister, who died in 2014 at the age of 24). The word “aftermath” is a tricky one, because there is no neat and tidy “after” violence or grief, particularly when one considers the varying scales on which various devastations and mournings take place. One of the main narrative arcs of the collection, though, is that of becoming someone who can embrace love and joy and care and kinship even when those concepts have been weaponized or altogether foreclosed for all of one’s childhood and adolescence. And that’s a narrative that requires a sense of an “after” that I am deeply fortunate to have personally experienced. That’s the main tightrope the collection is invested in walking, which forms the through-line around which and with which its other preoccupations and obsessions orbit and collide.

EB:Wow, thank you so much for sharing all that, Sumita. I especially like what you said about the lack of a “neat and tidy” ending – isn’t that always the case when it comes to writing about things from our own lives? We want real-life closure but sometimes have to settle for just narrative closure instead.

I meant to say also congratulations on the publication of your collection not only in the US but in the UK as well! What was it like to put that version together? The same? Different?

SC:I was wildly lucky in this regard. Some years ago, I published the poem “Dear, beloved” in Poetry, before it was in Arrow—and in fact before this version of Arrow even existed. At that point, the editor of Carcanet reached out to me to say that the press would be interested in bringing out my collection in the UK. I kind of panicked!

EB: I totally would have, too!

SC: As I mentioned, there was no Arrow yet. I was on a much earlier version that was “complete,” but when I looked at it, I knew: This ain’t it. And querying US presses was therefore not something I was prepared to do at that time; UK publication was even less within the realm of my imagination. I essentially told them the manuscript was in progress and asked if I could reach back out when it was ready and if I had secured a US publisher. Some years later, the collection was picked up by Alice James in the States and I reached back out to Carcanet to see if they were still interested, and they were! Alice James and Carcanet worked together during the production process, so while there were certainly some differences in approaches across either side of the pond, much of it was really streamlined, and that is all thanks to the outstanding and immense labor of the extraordinary editors and staffs at both publishers.

EB:How did you begin writing poetry in the first place? What was your path to becoming a writer?

SC: I didn’t come into much of a sense that I was interested in poetry and in literature until college. When I got there, I didn’t have a sense of really any passions and skills that I had, and that’s not imposter syndrome speaking—it’s because I had a terrible record in high school and found nothing inspirational there, and I was also pretty busy attempting to survive the violence I was experiencing at home and working toward moving out, which I did before college. In my first year and my sophomore fall at Wellesley, I took a really broad smattering of courses, including (with wild, and probably inappropriate, disregard for prerequisites in both cases) Advanced Shakespeare with William Cain and Advanced Poetry Writing with Frank Bidart. I was very much not good enough for both of those courses! But even as I was flailing around in them, something in my mind clicked: this was something I was willing to be terrible at until I started to understand it a bit better. These were puzzles that I liked, questions I liked, problems I cared about dwelling with. It was pretty much “love at first confusion.”

EB: I love that idea: “this was something I was willing to be terrible at.” That 100% nails how I feel about writing, too.

So, obviously, as you just said, Wellesley was very important in your trajectory as a poet – the title of your book is a reference to a Frank Bidart poem! Which other faculty, staff, fellow students have influenced or inspired you? Are there any professors or classes you would tell young Wellesley writers that they 100% have to take?

SC:Following “love at first confusion,” I essentially made a second home of the first floor of Founders, so my answer to who at Wellesley influenced or inspired me could fill multiple pages!

EB: I love Founders. I miss Founders.

SC: I will invariably accidentally leave someone out and feel guilty, so I offer my mea culpas in advance. In addition to Bill Cain and Frank Bidart, I am beyond grateful to Dan Chiasson, with whom I worked on both my literary studies (including my thesis) and my poetry, and who graciously offered me more mentorship than I’d ever experienced in my life before that point; to Kate Brogan, from whom I got the bug for twentieth-century poetics, which remains the focus of my literary studies research; to Yoon Sun Lee, who taught the theory class when I took it, and planted a hugely important seed that I didn’t even know had been planted until much later simply by being a brilliant Asian American literary scholar (not a role I had ever before seen filled by someone of this subject position); to Larry Rosenwald, who was the first person I had ever met in a literary context who both knew that English was not my heritage language and, in his infinite and genuine passion for multilingualism, viewed that fact as a strength.

I wish I’d had more of a chance to get to know my peers while actually at Wellesley—my life circumstances while I was in college differed from the typical Wellesley experience in ways that made doing so challenging (for one, I worked multiple jobs the entire way through), but I’ve gotten to better know many people I knew at Wellesley more in the years since and that’s been a wonderful experience.

EB: I’ve also made a lot of Wellesley friends post-Wellesley. The Wellesley experience never ends, in that way.

SC: Since I’ve already spoken to the coursework that inspired me, I’m going to zig a bit where your last question zags: there isn’t a single course I would tell young Wellesley writers or literary enthusiasts that they 100% have to take. I don’t think one could go wrong with anyone I’ve named here (and I’ve been really excited to learn about the new additions to the English department: I would have loved to have learned from Cord WhitakerandOctavio González, and have heard wonderful things about both!). But I think that what made the Wellesley experience truly influential for me was that I had the opportunity, like Whitman’s “Noiseless Patient Spider” (though, um, not very noiselessly or patiently), to “launch’d forth filament, filament, filament,” and really listen to what spoke to me. I came in with no preconceptions, no expectations, no firm career plan (or even career plan). Knowing what undergraduates at environments like Wellesley frequently pressure themselves or feel pressured to do (or achieve or produce or attain), I don’t want to offer advice along the lines of a “must-do.” Rather, try things out and truly listen to yourself. What’s your “love at first confusion”?

EB: I know from personal experience that writing can be a really lonely practice. Who did you rely on for support during those really frustrating writing moments? Other writers? Your spouse? Friends? Fellow Wellesley grads? What does your writing/artistic community look like?

SC: All of the above! The thing is, for me, I don’t think writing is a lonely practice. When I feel most energized about writing, it is because I feel like I am in a conversation—or, to put a finer point on it, when I’m in a conversation that is nestled within hundreds of thousands of other conversations that have happened for millennia, are currently happening all around me, and will continue to happen after I’m a hunk of dirt. Tapping into that is often what brings me to the page in the first place.

EB: That’s such a good point.

SC: So when students, for example, feel really isolated or alone in their writing life, my first recommendation is to remind themselves of their beloveds. These may be actual living ride-or-die humans in their lives; these may be ghosts of writers and artists past that are important to them; they might be their most frequently bustling group text or their favorite TV show. Honestly, if one’s thinking of this question as broadly as I recommend, those beloveds probably belong to all of the above categories, to some degree. When you write, even if none of these beloveds are your subject or your audience or anything quite that easily analogous to the process, they are with you, and they have formed who you are before you’ve even picked up a pen or turned your computer on, so they are with you when you are writing, too.

EB: What is it like to now be teaching poetry to undergrads? Are you channeling your inner Dan Chiasson?

SC: Ha! Thank you for that—I just got a visual of myself trying to go as Dan for Halloween and I cracked myself up. (Dan, if you’re reading this: sorry!) I teach undergraduates and graduate students at Michigan, both in literary studies and in creative writing, and I love it very, very much. My students of all levels are brilliant, thoughtful, curious, and wildly imaginative people who often help bolster my faith in the ongoing importance of literary work. Honestly, particularly during this year, I have frequently been in awe of my students and have felt overwhelmingly lucky to be able to work with them.

EB: I know that you are also currently working on your first scholarly book, Grave Dangers: Death, Ethics, and Poetics in the Anthropocene.How do you approach writing poetry vs. writing an academic work? How is your creative process similar or different?

SC: For me the two have been inseparable since Wellesley. I essentially ask similar questions and have similar preoccupations no matter what genre I write; in terms of deciding which thought belongs to which genre, or which project a particular moment is better suited to, that’s often a matter of thinking carefully of what shapes that I want the questions to take, and what kinds of “answers”—in quotation marks because I don’t strive at certainty or mastery in either genre, or in anything for that matter—for which I imagine reaching or searching. For me, the processes for writing both are very, very similar: I draft wildly and edit painstakingly. It’s more a matter of closely listening to my patterns of thinking on any given subject or day in order to find out if the rhetorical patterns of academic prose would better suit them or if the rhetorical patterns of poetry would better suit them.

EB: What are you currently reading, and/or what have you read recently that you’ve really enjoyed? What would you recommend to read while we (are continuing to) lay low during this pandemic?

SC:2020 was such an incredible year for books! Which feels somewhat perverse to say, considering everything else was dismal and it was hardly an easy year to put out a book, either. In terms of new poetry releases—and this is not a comprehensive list, so my mea culpas here too to the many that I have loved and will end up accidentally leaving off—I have this year read and loved: Taylor Johnson’s Inheritance, francine j. harris’s Here is the Sweet Hand, Craig Santos Perez’sHabitat Threshold, Jihyun Yun’sSome Are Always Hungry, Eduardo Corral’sGuillotine, Rick Barot’sThe Galleons, Jericho Brown’s The Tradition, Shane McCrae’sSometimes I Never Suffered, Victoria Chang’s Obit, Danez Smith’s Homie, Aricka Foreman’sSalt Body Shimmer, and Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem. Two prior-to-2020 poetry collections that I reread every year are Brigit Pegeen Kelly’sSongand Lucille Clifton’s The Book of Light. I’m currently reading Claudia Rankine’s Just Usand Alice Oswald’s Nobody.

EB:Also what about Lucie Brock-Broido? I know she was a teacher of yours at one time, and she was a professor in my MFA program. I had the pleasure of once sitting in on her lecture, and it was life-changing. Are there any particular poems of hers you would suggest?

SC: I joined Lucie’s summer workshop held at her home in Cambridge, MA the summer after my sophomore year at Wellesley, and I stayed in it until I moved to Atlanta for graduate school in 2012. “Life-changing” is right—in fact, it feels a little too modest. She was transformative. A cosmos-realigner. A hilarious, brilliant, extraordinarily kind meteor. A fox with wings. A unicorn. I could go on, and on. For a reader new to her work, I’d recommend starting with her posthumously published “Giraffe” in The New Yorker. I think “A Girl Ago”and“You Have Harnessed Yourself Ridiculously to This World”fromStay, Illusion(2015) are also remarkable entry points. After that, I would probably recommend reading her collections in this order: first Stay, Illusion; then A Hunger (1988); then The Master Letters(1997); and finallyTrouble in Mind(2005). The sequencing here isn’t intended as a ranking in the least—my own personal favorites toggle back and forth depending on where my own “trouble in mind” lives, and each collection is dazzlingly strong and has its own raison d’être—but rather because I think the story those collections tell in that order would let a new reader have a full sense of Lucie’s poetics outside of the story that mere chronology can tell.

EB:Any advice for aspiring young poets?

SC:Filament, filament, filament. Let your writing life be as huge and wild and disparate as the whole person you are—don’t feel like there’s only a part of you that’s “worthy of poetry,” and don’t let anyone else tell you what kind of writer you should or shouldn’t be.

EB:Thank you, Sumita! That was wonderful.

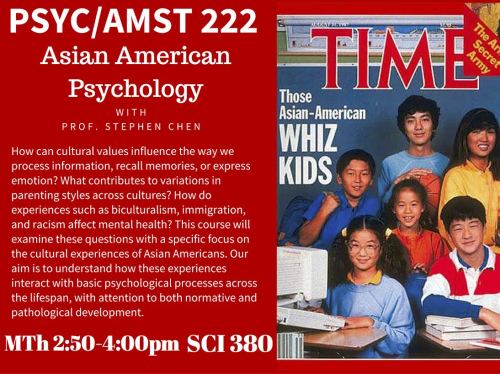

Interested in understanding Asian-America through a psychological lens?! Or perhaps passionate about mental health issues as they manifest in communities of color?! Register for:

PSYC/AMST 222: Asian American Psychology

Post link

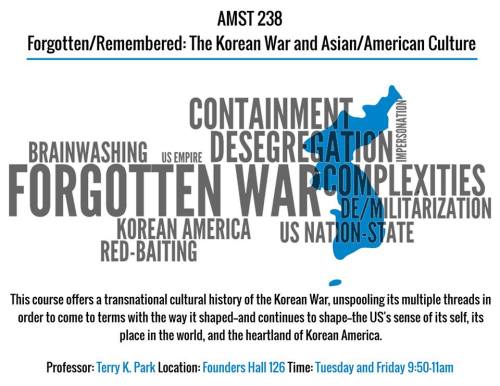

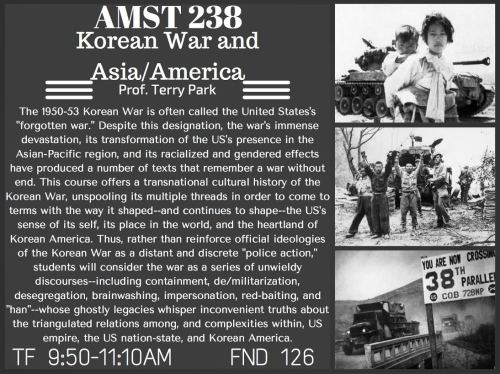

WELLESLEY FRIENDS! Still looking around for a last class?! Interested in AA Activism, Ethnic Studies, or the consequences of U.S. Imperialism?! Register for

AMST 238: Forgotten/Remembered–The Korean War and Asian/America

taught by *new hire in the American Studies Dept, Terry Park!*

(who also served as a former Executive Director of Hyphen magazine!!!)

Post link