#brenna yovanoff

The morning starts like other bad mornings, paranoid and full of dark suspicions.

When I come into the kitchen, he’s got the coffee maker pried wide open and is looking down inside it for a hidden camera or a transmitter or a secret service bug.

Addy’s sitting under the table watching the proceedings with her legs splayed out in front of her, loving on that ratty plastic doll.

“Dad,” I say, taking down a box of cereal. “Could you not?”

He glances at me, brandishing the flathead. “They think they’re so smart, but I’m onto them.”

His voice is triumphant, inviting me to ask who, but if we do this right now, I’ll be late getting to school, and I’m not in the mood.

I look down at disheveled coffee maker, then back at him. “Please, I just want to get a cup of coffee and I can’t do that if the thing’s in pieces.”

My father doesn’t have just one definite mood. There are versions of him, different on different mornings. You never know who you’ll get. My father, embarrassed and contrite, anxious to apologize, or my father ranting.

Today, he smiles, and mercifully hands over the screwdriver. “My little girl likes her coffee and that makes two of us. Two of a kind. Two peas, pigs, birds with one stone—”

The listing could go on forever, once he gets going. It jerks out of him like a stutter, a tic he can’t control.

I nod and pinch the bridge of my nose, opening the refrigerator and muttering, “Or maybe, I just like it because I like it. Ever think of that?”

He whirls on me, and in one awful moment, I’ve ruined the tenuous peace between us, shattered it with backtalk and disagreement.

“Dad, I’m sorry. I mean that I like it because you do. That’s why. That’s what I meant.”

He doesn’t answer, just turns and walks out of the kitchen. I smile reassuringly at Addy, who smiles back and waves the doll at me. When its head flops forward, it looks like it’s nodding.

I barely have time to pour a bowl of cereal, before there’s the clatter of footsteps on the stairs and he’s back, carrying a huge armful of my clothes. He crosses the kitchen and yanks open the back door.

“Hey,hey! What are you doing?”

My sweater hits the ground like a buck-shot bird—flapping through the air for a breathless moment, soaring, then bang. It tumbles out of the sky.

“Get out,” he says. “Get out, get out, get out.”

I keep a phone number taped under my bed, because I know he won’t look there. The contact information is encrypted and I know that even he can’t break it without the key. The number is for a social worker. There are other places I’d need to call, too. But the social worker is the one who will list them all. Who will tell me what to do.

“Dad,” I say, reaching for his arm. I’m used to this, the tantrums and the accusations. I’m used to this, but I can’t say that it doesn’t hurt anyway. My clothes are everywhere and I’ll be a good long time picking them up off the lawn.

“You’re a liar,” he says, tossing away a faded T-shirt. “You don’t fool me. You know the truth, you know! You know it because you’re—just—like—me!”

The pronouncement stuns, wounds, hits me in the chest like a bowling ball, but I close my eyes and bite down on nothing, clenching me teeth so the abject horror won’t get out.

For a second, I think I’ve succeeded, made my expression blank as a dinner plate.

Then he plunges at me, putting his face close to mine. “What did you say? Don’t you mumble at me, missy!”

“I didn’t sayanything.”

He rifles through the pile and there goes my plaid Christmas dress. “Don’t you go whispering at me!”

I retreat from the kitchen with Addy scampering after me, and leave him chucking my things out into the yard.

In the living room, my older sister, Meg, is sitting on the couch with her ankles crossed, resolutely ignoring him. She has the TV turned up obstinately loud.

“We need to call,” I say, hearing fear and then resentment come spilling out in my voice.

Meg and Addy just stare at me. Meg’s hands look small, oddly delicate next to the ungainly bulk of her body. Addy sits on the carpet at her feet, petting that mangy doll, over and over. Rubbing its hair right off.

“Well, I’m calling,” I say.

Neither of them move. Their answer is in the fact that they don’t try to stop me.

The social worker is tiny, an olive-skinned woman with a storm of curly black hair.

“I’m glad you made the choice to ask for help,” she says in a low, soothing voice.

We’re sitting out on the porch, drinking tap-water lemonade that I mixed from a packet.

I study my glass. “What’s going to happen to us?”

“Well, I’ll be doing my best to keep you together. I want you to know that, but it is harder with big girls. Doesn’t mean it’s not worth a try, though.”

“No, I mean, what’s going to happen to us? Are we going to wind up like him?”

“Oh honey, let’s not borrow trouble. You don’t want to talk about this right now.”

But I can’t shake the raw intensity of his voice, his face too close, his eyes looking startlingly like mine. “Yes, I do want to talk about it.”

“Well,” she says, with her gaze drifting off over my head, “statistically speaking, there is a chance that one of you could exhibit … symptoms at some point in your life. But this is really something to talk about with a psychologist.”

Addy comes creeping up behind me in that way she has, not touching me, but hovering beside my chair. She slumps forward and leans her chin on my shoulder.

She whispers, “One bright day in the middle of the night, two dead boys got up to fight.” Her voice is sweet and dopey, and even on good days, she doesn’t make an awful lot of sense.

I watch the social worker, whose hands are working at the hem of her blouse, but whose eyes have never left my face. “I’m worried about her.”

“Worried about who?”

I jerk my head to the side and feel traitorous when I whisper it. “Addy.”

“And who’s Addy, honey?”

The weight of Addy’s chin digs into the side of my neck. “Here’s how much I love you,” she whispers, tickling my ear with the busted-up doll.

“My sister.”

“I thought your sister’s name was Meg.”

“My other sister. My little one.”

“Oh.” The social worker blinks and shakes her head. “Oh, I’m sorry. Somehow, I thought there were only the two of you. And where is Addy now?”

With her chin on my shoulder and her arms tight around my neck, breathing in my ear.

The social worker is watching me, hands tugging harder at her blouse.

“Don’t,” I say, feeling the panic well up in my lungs. “Don’t mess with me.” Although I know in my darkest heart of hearts that she wouldn’t.

She’s looking at me with wide, nervous eyes. With doubt, and it’s the doubt, more than anything, that makes me go cold.

“You’re a bad girl,” says Addy. “Now say you’re sorry for what you did to Daddy. Say sorry, and I’ll give you a kiss.”

“I’m sorry,” I say, shaking my head at the social worker. “I’m not making much sense. It’s been a long day. I’m sorry.”

Addy’s mouth is warm against my cheek, the sticky, fumbling kiss of something too strong to pull away from. Rooted in my brain, my dark, uncharted blood.

Too close to family.

Story originally posted December 7, 2009

Photo by zen

One of these days—soon—without word, without warning, I’m going to go up in smoke.

It won’t sputter or smolder. When the blaze finally comes, it will be a conflagration. I’ll explode into flame like a dynamite crate, blackened paper and broken boards going everywhere. One of these days, the weight of the feathers and the silk will be too much. My bones will break like matchsticks, splintering, striking sparks off the edges of my cold steel core.

Two times since rehearsals started, the footlights have gone out during the Pas de trois. Back in November, it was raining all the time. The breakers kept shorting, crackling out in a shower of sparks. It wasn’t anyone’s fault, but someone had to answer for it. The new director told the stage crew that if it happened again, heads would roll. We could hear her through the door of her office, screaming into her phone. The pitch of her voice was inhumane, and directors all are crazy. They’re supposed to be temperamental, dramatic. This is different. When Madame de Sevigne raises her voice, it’s like a struck bell that won’t stop ringing. You can almost hear the frequency of her stiff, violent rage, buzzing under her skin.

Three of the corps dancers quit in one week, less than a month into the season. The ones who stayed called it madness, leaving the best company in the state, but those three were done and even their little-girl dreams of being pretty ballerinas weren’t strong enough to keep them here in the glowering presence of the Madame. They gathered up their lace and ribbons and disappeared, leaving nothing but a few loose hairpins and sequins, a few scattered feathers.

Four is the count, the steady rhythm repeating on the floor. It’s the plodding song of the metronome. We bend and grow to it, stretching and swaying—up, down, over. We fold and crouch, silent. Low. They treat me like their queen, but that’s a lie. It’s Madame who reigns over us. We are all prostrate before her.

Five nights a week, the company rehearses. And spends those rehearsals wishing it was one of our days off. I’m the girl who never murmurs or complains. The others take my silence as indifference. They make assumptions that I’m cutthroat and hungry. That I take all the good things for myself, but that’s only an illusion. I’m just as caught, as tangled-up as the rest of them.

Six times, the Madame has made an example of someone, calling them to stand apart and take their punishment. Six times, I’ve stood silently in the crowd and wished that it was me. Sometimes, if you have to watch, the humiliation is too much. It’s better to bow your head and take the blame. If you can just save all the scorn and the reproach for yourself, sometimes it means that everyone else is spared.

Seven is the number of pounds that Marianne Porter has to lose if she wants to keep her spot. When Madam de Sevigne told her that, in front of everyone, the rest of the swans turned and angled their faces to the floor while I stood apart, with my back straight and my head up. Marianne didn’t argue or protest. She stared greedily at me, the body that Madame holds sacred. The one they’re all supposed to covet, aspire to and emulate. Later, I found Marianne alone in the dressing room, drawing X’s on her stomach and thighs with a marker. I could see her spine through the taut, uncomplaining veil of her skin.

Eight is when we stop for the evening, if the Madame is pleased and the rehearsal goes well and the stars align. We never stop at eight.

Nine is the number of circles Madame draws in her black choreography notebook before turning the page. I’ve seen her backstage, or else sitting stiffly behind the desk in her office, drawing her vicious little circles, making her little notes. She doesn’t glance up or look around, lost in the magic of her book. I think it’s where she keeps our souls.

Ten is the number of toes I have. It’s an ordinary number, but every night, I wonder. I slide them out of my pointe shoes, and it always seems for a moment that the shank and the toe box have molded them together like the gnarled feet of a bird. The other dancers gasp and wince. They cry noiseless tears until the ache stops and the numbness creeps back in. They bend their heads to hide the pain, until their whole bodies look pale and distorted, like fairytale creatures. I think that she’s bewitched them into swans but left me half a princess—a feathered girl made of skin, muscle, bone.

Eleven is when we stop for the evening, since we never stop at eight. The lights flick out and the music trails off. Everything has to stop sometime.

Twelve o’clock is soft and full of shadows. The building is empty, echoing. Still.

The only one left now is Madame, sitting grimly behind her desk.

She didn’t take my voice. My silence is legendary, but she’s not the reason I don’t speak. The other dancers stare around, craven and wide-eyed like she’s fixed their mouths, filled them up with feathers.

My own voice is still right where it belongs.

The door is cracked, and when I push my way into the office, she doesn’t look surprised. When she asks what I want, I tell her that the corps is frightened of her, that more might leave if she doesn’t start using some compassion, or at least some tact.

“Thank you for bringing it to my attention,” she says. “I appreciate your input, but really, the state of the corps is not your concern. If you’d like something to worry over, you ought to be thinking about your arabesques.”

She says is briskly, like the words are prerecorded, before going back to her nasty little book, listing off our flaws and weaknesses and our faults, recipes for destruction. All the perfect, constant circles.

Alone in the hall, I understand that my visit hasn’t made a difference. I didn’t expect it to.

The swans are useless, mute, and I can’t make them into real girls. They might wish for protection, for rescue, but they don’t love me. They’d burn me like a witch if they could, and maybe the secret to being the best is that you don’t mind too much when your feet hurt or other people want to burn you.

The cavernous space behind the stage is cluttered, all ropes and wires and dangling sandbags. There’s ancient wood paneling peeling up from the floor, water dripping from places the maintenance crew were supposed to patch. I wind my way through the boxes and the pulleys, carrying one of the cygnet’s tutus from the dressing room. The feathers are scratchy and coarse against my arms, much coarser than they look.

This is the one elemental truth of a swan princess. The truth of Madame.

Without ceremony, I toss the skirt over the rickety fuse box, and trip the breaker.

Story originally posted January 2, 2012

Photo by Skye Inominatus

All the Avett girls are strong swimmers. In a county of cattle ropers and turkey shooters, this is what we’re known for. There’s nothing more peaceful than diving below the surface. The lake is my secret, my refuge.

But this is not a love story.

Asher Phipps is four years younger than me, but a good deal taller. When he was hardly more than a baby, his daddy, Otha, died in a threshing accident. Afterward, Asher’s momma was no good for anything anymore, so he started tagging after me. He had a sweet country lisp and a toy duck on a string. He used to follow me everywhere.

I watched him on yellow afternoons, showed him how to make pets out of beetles, and dolls from corn husks, took him swimming in the creek.

Now, he’s mostly grown and we haven’t spoken in years, though I still see him nearly every day in the summers. Sometimes, his mouth is open like he’s about to say something, but the sound never makes it all the way out. Sometimes I catch him looking at me, this raw, ragged look that I don’t know how to answer.

Before this business of misfortune and grief, he was the golden one, hero-strong and best-loved. As for me … well, I’m the girl from the lake. It’s been a long time since they didn’t find me strange.

Asher’s change was sudden, whereas mine happened so slowly that no one could make note of it for sure. I might have always been this way.

It wasn’t his momma dying, although that happened. And it wasn’t the recession, or not getting that scholarship. All those things were bad enough, but when he lost his sweetheart, his store of strength, of perseverance seemed to end.

When she died, the whole town turned out for the funeral. I did what I always do—went out to the lake and swam deep, looking for answers. In the murky glow of a stifled sun, I saw blackness and shadows, indistinct. I saw nothing.

This is not a story about revelations.

Before there was the lake, the town was situated at the lowest point in the country, snuggled in tight between two hills. When the steel plant came in, they needed water for cooling. They tore down the houses, carted out the planks and shingles. They left the foundations like a monstrous ruin, a long-forgotten world down in the weedy tangles and the mud.

On most days, I visit. I swim out to the middle and dive right down to the bottom. There in the gloom, I am closer to our past, running my fingers through silt and slime, reaching for a world that used to be ours, all lawns and carports, leaning garden sheds. Avett girls can hold their breath forever. I wind my way between rotting stumps where trees supported tire swings. We used to live here. I would live here again if I could.

This is not a story about coming home.

Asher runs what used to be his daddy’s bait shop, only now I guess it’s his. The shop was there when people used to go fishing in the creek, and now that the lake has taken over, the shop stands farther up the slope, just off a pair of barbecue pits and a rickety picnic area.

During the slow hours, Asher sits out on one of the broken-down picnic tables, waiting for sunset, for closing time. The girls from town come twitching around to see him, smiling cherry-red smiles and flirting with their eyelashes. They all want him to take and marry them, if only to have that triumph, to prove they each are fine enough that he’ll love them. If they can make him love them, then anyone will love them. His eyes are always somewhere off in the middle distance, and tragedy has a glamour to it, if you only wear it right.

This is not a story about sorrow.

It’s a slow, hot evening in August and when I come trudging up from the lake, I’m not startled to see a herd of girls gathered around Asher.

He looks up, looks past Annalee Marquart and Callie McCloud, to where I stand with my dripping hair and sopping canvas shoes.

“Viv,” he says, and his voice sounds cracked and rusty. Just my name. Nothing else.

Callie glances over her shoulder. She’s younger than me, but aggressively put together, with curled hair and heavy lipstick. When Asher stands up and pushes past her, she looks stricken, then furious.

He comes across to me, eyes fixed on my face. In the trees, seven-year cicadas are crying clear to Colvern County. “Viv,” he says, “can you tell me something? Just tell me what it’s like when you dive?”

And I don’t say anything, because it’s not the kind of thing you can say. I know what he’s asking, but that’s not the same as knowing how to answer.

I would comfort him, console him for his loss if I were still his friend. But was I ever?

This is not a story about loneliness.

How can a person ever know the true, honest heart of another?

This is what I’m thinking as we stomp and thrash our way through the canebrake with black flies and no-see-ums whining around our heads. This is what makes the goose pimples come out on my arms and the shudders run through me. Not the chill of my wet clothes, not anticipation of the crisp, authoritative splash when I break the surface. But this, this certainty that Asher is too far from me now to ever know me again and yet, he wants an antidote, expects me to cure him of his pain. At the bottom of the lake, there are the gloomy shipwrecks of memory, but no answers.

Fools like to talk about the little town church. They say it wasn’t dismantled, but only left behind. They claim the steeple stands even to this day, dark and ghostly, just visible when the water gets low. That’s nothing but a tale. I’ve been down a hundred times and never seen it.

This is not a story about God.

Asher wades out first. Just stumbles forward and plunges in. If it were me, I’d have walked farther down the shore, to where the bank slopes off and the ground is all bare gravel and fine sand.

He goes deeper, water churning up around him, and I’m struck by how badly I want to comfort him, fix it all if I could. I raised him half his life, but that was years ago, and it’s taken me this long just to uncover the mysteries of the place I grew up. I don’t know him anymore than he knows himself.

From the bank, I watch him flail away from me, toward a world he can’t survive and can never understand. The world on the bottom is mine alone, not because I conspire to keep it, but because no one else in the history of our incurious little town has taken the time to explore it.

“Asher,” I call, and then start after him. “Asher, wait. Why are you doing this?”

“Because you’re the only other person who knows what it’s like,” he says, looking back over his shoulder. “Because you know how it is to wish and wish for something you can’t ever have back.”

“It was never like that.” And now I’m splashing after him, shaking my head. I say it unashamedly and right out loud. “I never loved our town until they sunk it.”

He stops.

He nods, but won’t look at me, standing hip-deep in the artificial lake, run through on the realization that I’m not broken. That he is wholly alone in his sadness, when all this time, he’s been so desperately sure it was the two of us.

His eyes are a pure, moody ice-grey, like swimming out to the center. Like going under.

This is not a love story.

Story originally posted January 4, 2010

Photo by flaneurin

When Brandon Rowe was eight years old, he hit a squirrel with a rock and broke its back. I know because I was standing on the other side of the fence, watching.

After he went inside, I climbed into his backyard and crouched over the squirrel. I petted it. Its fur was soft and felt like the collar on my mom’s winter coat.

When I carried it home wrapped in my shirt, my mom told me not to touch it, it was dirty and I’d get a bad disease. My sister Rosie, who was in eighth grade, helped me make a bed for it with a shoebox and some rags. When I picked the squirrel up to set it in the box, it looked at me with one shoe-black eye and made a noise like a rusty can opener, but it didn’t move. Rosie showed me how to give it water from a plastic dropper. Then she took me in the bathroom and made me wash my hands.

She said, “It might die tonight, okay? If that happens, don’t be scared. Just come get me.”

Iwas scared, though. The squirrel was little and soft. The room smelled like Dial soap, and I tried not to cry.

“Oh, Noah, don’t be sad. Things die from shock sometimes, is all.”

I spent all night lying on my floor next to the box and watching the squirrel breathe, putting my hands on its back, feeling the places where the bones didn’t line up. The squirrel twitched and shook. Then it stayed still.

I was seven. What did I know? In the morning, the squirrel was still breathing, and when it climbed out of the box and whisked in circles around my room, I was the only one who wasn’t surprised.

When Brandon was twelve, he broke my best friend Milo’s pinky finger. We were down at the community pool and Brandon pushed Milo off the diving board and jumped in after him, even though Milo was still splashing around like a drowning cat and couldn’t get out of the way.

Brandon crashed down on top of him, and when Milo struggled back up to the surface, the look on his face was all shock and white-lipped pain.

After Milo paddled awkwardly over to the side, we sat on the edge of pool and I studied the damage while Brandon stood over us, calling us a couple of whiny little gaywads for holding hands. I looked for guilt or pity in his face but didn’t see it. His grin was so wide it made me feel uneasy, and like the world was a pretty out-of-control place. Milo’s hand was swelled-up, already turning purple.

“Hold still,” I said, and Milo nodded and squeezed his eyes shut.

“What are you going to do?” he whispered. His face was so pale he looked gray.

“Nothing. Just hold still.”

The hardest part was setting the broken ends back together. Milo kept his eyes closed, swaying a little on the edge of the pool. I held his hand between both of mine and waited for the rush of electricity that would mean it was working.

“What a couple of queermos,” said Brandon, and I tried to tell myself it was because he was secretly sorry, but I didn’t believe it.

When Brandon was fifteen, we had PE together. The class was supposed to be for freshmen, but he’d skipped so many times the year before that he had to take it over.

On the second day, he hit Melody Solomon in the face with the volleyball. He did act sorry that time, but only because she looked like a cheerleader. He wouldn’t have cared if the same thing had happened to one of the fat girls, but Melody had shiny hair, nice legs, and a very good tan.

When he tried to say he was sorry, she twisted away from him, cupping her hands over her face.

“Here, let me see,” I said, reaching for her shoulder. She jumped like I’d startled her, but didn’t recoil the way she had with Brandon.

When she took her hands away from her face, blood was running down over her bottom lip and dripping off her chin.

“Is it okay if I touch it?”

She didn’t look at all sure about that, but she nodded.

I ran my fingers along the bridge of her nose, feeling for the break. It was high up and to one side. When I pressed the cartilage back into place and held it there, Melody winced and tears leaked out of her eyes. She was watching me with this numb, pleading look that reminded me of the squirrel and how it stared at me defenselessly, like it didn’t have a choice. Her eyes were gray, with pale starbursts around the pupils, like tiny metallic suns.

Behind me, Brandon made a thick, disgusted noise. “Oh, gross—don’t let Noah touch you or you’ll get his nasty-ass stink all over you!”

And Melody flinched and pulled away. Her expression was frightened, almost lost, and I could still feel tingling sensation the in my fingertips.

Brandon laughed and pushed me hard between the shoulder blades. “You don’t know where he’s been, Mel. I’ve seen him out on Garner Street, playing with the roadkill.”

And it was one afternoon, hot and dismal, and one panicked shuddering dog, but it didn’t matter. For the rest of the year, everyone called me skunk-boy. Melody’s nose healed straight and perfect, but she never looked me in the face again.

When Brandon was seventeen, he shattered his right ankle in a car accident. He also broke his collarbone and fractured his left femur. It happened the week before soccer started and the accident was pretty much the end of his season—maybe the end of all his seasons.

He missed a lot of school and being the good neighbor she is, my mom volunteered me to get his homework assignments and bring them over to his house.

I hadn’t been in his house since I was a little kid, and the few memories I had of the Rowe place weren’t good memories. When I came into the living room, Brandon was sitting in his rented wheelchair in front of the TV, watching like he wasn’t really seeing it.

I dropped the stack of make-up work on the coffee table and he didn’t look up. I was used to him vicious and laughing, but now he just looked resigned. He looked like he hadn’t been sleeping.

“The project for history is a research paper. Give me your list of books by Thursday and I’ll get them from the library.”

When he still didn’t say anything, I turned and started for the door.

“Are you going to do your crazy-voodoo laying-on of hands thing?” Brandon’s voice was low and flat and when I turned around again, he was still looking at the TV. “I mean, isn’t that what you do?”

I didn’t answer. There were plenty of things I should have said—excuse me?orI don’t know what you’re talking about—but the truth was, I kind of wanted to.

His injuries were bad, worse than anything I’d ever seen—worse than dying squirrels or skinny, shivering best friends or beautiful girls in PE. And yes, I wanted to find out what would happen if I tried my touch on a really bad break, one that might never heal right, even with pins and screws.

Brandon sat in his chair, looking up at me, and my hands felt hot. My skin was singing with adrenaline, a wild electricity that couldn’t wait to jolt out of my fingers and into bone. I knew, without a doubt, that I could do it—knew with ninety-nine percent certainty. Except.

Except, I didn’t feel pity when I looked at him. Except, I’d spent more than half my life mending bones and now, in the tips of my fingers, something didn’t feel right. My hands were hot.

Brandon watched me without saying anything, and then his face changed. His stare turned hopeless and painful, like he knew there was cruelty sparking off my fingertips, burning in my blood. He could see it on me, before I was even sure that it was there.

“Jesus, Noah,” he whispered, and his voice sounded tired and almost frightened.

“You don’t want me to touch you,” I said. “It wouldn’t work out.”

Story originally posted August 23, 2010

Photo by Melanie Hayes

I. The Waiting Room

They come to the forgetting place when they are too shaken and too damaged to remember. They come when they can’t accept or move on, when they can’t let go.

The living aren’t the only ones who cling to tragedy, grieving for things they can’t change. The dead can be just as mired in the past.

II. Max

He is standing against the wall. At least, he thinks he is standing—the sheer uncertainty of being dead makes it hard to know for sure, and sometimes he suspects that he is only acting out the illusion of a body, not wearing the actual thing.

He’s watching four grizzled men play poker with the stone-faced seriousness of bankers. They don’t speak as the deal passes from one to the next, and it seems to him that they have never not been sitting exactly like this, one on each side of the card table.

The game is silent and grim. It leaves no room for anyone else. Not that he has any inclination to join in.

His name was Max, and he still goes by it. At least, he is Max to anyone who cares to call him anything. Most of them are politely indifferent to him, sunk deep in their own misery.

Like the four men at the card table, they are all living out their own tragedies again and again, wandering the forgetting place until it coaxes them into remembering and they can finally move on.

III. Emily

She is pale and beautiful, almost unbearably so. Her beauty is fierce, an integral part of her, while her paleness may only be an interesting side effect of being dead.

She is the weeping ghost, and he loves her in the thin, desperate way that only shades can love—transparent and uncomplicated. Pure as glass.

He doesn’t remember meeting her, only that it was after he came here. He thinks that she has always been beside him, tears streaming down her cheeks. She has never once looked at anyone else.

The way he feels about her is the only thing about the place that doesn’t make him feel trapped. His love is, against all reason, growing stronger. This, this steady deepening is the only indication that time is actually passing.

When she turns her eyes up to meet his, he feels as though his heart, which does not exists, may start to beat again. Her gaze is steady, excruciating, and he thinks that if he keeps looking, he will get lost there. His love for her is enormous and acute, and sometimes, it seems to have the power to transform him.

Everything else just stays the same.

IV. How He Died

With a flash of light and a burst of noise. With a bullet in his brain and his eyes turned blankly toward the ceiling. He died with a gun to his head, but it might as well have been a knife in his back.

When he thinks about that night, he still remembers everything. Coming home to his young bride, a woman with a hard, unreadable gaze, a smile like a sphinx. How he trusted her and she lied. The memory is simple. He can’t think why he should still be trapped here in the forgetting place, but he is grateful anyway.

Without his quick, brutal death, he would not have Emily, and because he remembers that death with the jumbled clarity of nightmare, he is troubled by the nagging fear that at any moment, he will be plucked from the forgetting place and spirited away, thrust into an endless afterlife without her.

After all, he knows the truth—has known it from the second the gun went off.

He died from giving his trust to a dangerous woman. From loving too much.

V. What It Meant

Sometimes, she asks about his life before here. If he has ever loved anyone in the same pure, uncluttered way that he claims to love her.

“Never,” he tells her as she drifts there beside him, eyes red-rimmed like always. “I loved someone once, but she betrayed me—turned on me before I even knew what was happening.”

Emily smiles and he thinks that he has never seen anything more beautiful. It is the crumpled smile of tragedy, and tragedy is all that keeps them here. Her smile is his whole world.

“I killed my husband,” she says. “He was an informant, passing secrets to men who would destroy my family, and my father found out. I was so devoted, so in love, but I was loyal to my father.”

He thinks suddenly that this is too familiar. That they have had this conversation so many times. It almost means something.

He has a fleeting sense that he understands everything, but then the moment is gone and instead of trying to recapture it, he smiles and takes Emily around the waist. He kisses her lightly and thinks that he can almost smell the salt of her tears. He can almost smell blood and the hot, scorched-metal smell of the gun.

Then it’s gone and there is no flat, white explosion, no past. There is nothing, because something would mean staring straight down into the dank, murky well of the truth and if he remembers, they will be lost to each other.

The forgetting place is his whole world now, past, present, and future.

It is all he needs to know.

Story originally posted July 4, 2011

Photo by Paul Domenick

The apartment was small, but it was in an excellent location, right in the heart of the Warehouse District and a five-minute walk from the Expo Center. Adeline was only staying for a week or so—just until the trade show was over and all the boutique orders were in. Hopefully, there would be a lot of them. It had been a slow year.

The girl who usually lived in the apartment was a bartender named Daniele. She was away on a month-long trip to Spain and was renting out the place for ridiculously cheap as long as the temporary resident agreed to water her plants.

Adeline wasn’t much of a plant person, but you couldn’t argue with a weekly rate that was, quite frankly, phenomenal.

The night she got into the city, it was raining hard and the streets were flooded, full of tiny white-capped waves and floating trash. She had to wade from the taxi to the curb, holding her suitcases up out of the high-running gutters. It had been a long flight and everything had begun to blur together, so that later, she barely remembered the slow, clanking elevator ride upstairs, the turn of the key in the lock and the headlong fall into sleep.

She woke up late the next morning, in Daniele’s bed, with the sun coming in through unfamiliar curtains.

The first thing she noticed about the apartment was that the whole place had a smell. Not unpleasant, but strangely specific. It was an ancient, shut-up smell, like abandoned attics and pages turning into dust. It reminded Adeline of estate sales, or how she thought mummies would probably smell, but she found it oddly addicting. She couldn’t stop breathing it.

She took her time unpacking, arranging her things on the bathroom counter and the dresser, alongside Daniele’s. Then she wandered down to the lobby to see if there was anyplace to eat nearby, a cafe or a coffee shop.

Outside though, the road was blocked off by barricades and police cars and the sidewalks were crowded with gawkers. The girl at the front desk only raised her eyebrows and gave Adeline a bored look.

“What’s going on out there?” Adeline asked, feeling a little disoriented.

“Looks like some pure fool got it into his head to climb up on the roof and start yelling about how he’s going to jump. It happens in the summer, sometimes. If I were you, I’d just stay in ‘til it quiets down.”

So Adeline went back upstairs and spent the rest of the afternoon organizing her portfolio and hanging up her clothes. The show didn’t start until Monday and she supposed she could use the chance to settle into the apartment, which was full of area rugs and old, heavy furniture and framed pictures of Daniele, who turned out to be a pale, willowy girl with starlet-blond hair and too much eyeliner.

Adeline thought that she would make a good concept model. A muse for some up-and-coming fashion-peddler. Some other designer who specialized in ragged hemlines and liked to use metal studs on everything.

Maybe back when she’d been miserable small-town Adeline, with her grim, bleary childhood, her affection for the shrill and the destructive. Before she’d learned to leave the past alone and only focus on the here and now —before she wised up and got the hell out of dodge, left behind the old night-clubbing, chain-smoking Adeline and become the nervous, polished professional, who bought linen by the bolt and designed sensible-yet-versatile career sets.

The apartment was bigger than it had looked the night before and it seemed that every time Adeline turned around, she discovered some new alcove or closed door.

There was a little room just off the study that was decorated entirely in green, and one through the back of the bedroom closet that was filled with remnants of distressed leathers and dark, raw silks, and piles and piles of concept drawings. The outfits weren’t to Adeline’s taste, but she had to admit that some of them were pretty good.

The next morning, Adeline went out for groceries, only to find the elevator doors propped open and an old woman in a canvas coverall digging around in a battered toolbox.

“It’s not running,” the woman said without looking up. “You’ll have to use the stairs.”

The apartment was on the fourteenth floor and Adeline had to admit that even if she had the motivation to walk down, she didn’t really feel like lugging the groceries all the way back up.

“Will it be fixed tomorrow?” she said, a little doubtfully.

The old woman shrugged. “Should be, I guess. God willing.”

Adeline nodded. She went back to the apartment and sat in a high-backed chair in the living room, smelling the dry, dusty smell and running her fingers around the crochet collar of her blouse. There was a picture of Daniele on top of the old upright piano. Her hair looked darker than Adeline had realized. Her face was mysteriously familiar, like looking at a relative you hadn’t seen in a very long time.

Adeline closed her eyes and leaned back, feeling comfortable for the first time in months. Maybe years. She was glad she had decided to stay in.

The morning of the expo, Adeline spent forty-five minutes fixing her hair and ironing one of her career-casual dresses. Then she started out with her purse slung over her shoulder and her portfolio under her arm. But when she tried the apartment door, she found that it wouldn’t open.

She jiggled the knob, and then tried brute force, but it was stuck. When she called down to the desk, the phone rang for what seemed like minutes on end, but no one answered. By the time she hung up, her hands were shaking. She was supposed to pick up her badge at the registration table, and then be stationed at her booth in fifteen minutes.

She found Daniele’s number taped to the refrigerator and dialed it without much hope, but Daniele picked up on the first ring. Her voice was husky and musical.

“Is there a trick to opening the front door?” Adeline asked after the pleasantries were out of the way. “I mean, do you have to do something special to get out?”

“Yeah,” Daniele said. “You have to be kind of a badass.”

“Excuse me?”

Daniele was silent for a moment. Then she took a deep breath. “Honey, you have to be fierce. You have to know exactly what you want and how to get it. And the state you’re in, you’re not going anywhere.” It sounded like she might be smiling.

Adeline stood in the kitchen, swaying in her sensible heels and clutching her phone.

“I’ll miss my show,” she said. She tried to sound calm and reasonable, but by the time she reached the end of the sentence, she was nearly crying. “This is my biggest week of the year. I needthis.”

“Baby,” said Daniele and something about the familiarity—the absolute presumptuousness of it—chilled Adeline. “I know you want to be Target-famous and dress everyone in chic, durable neutrals and be a big girl and all that, but look at you. You’re falling apart.” Her low, husky voice sounded higher and more girlish suddenly. More like Adeline’s.

“What are you talking about? I was a Mod Madness pick for their Young Designers list. I’m a fresh new talent. If I keep my sales up, I’ll have my own boutique by the time I’m twenty-eight!”

She began to pace, drifting through the front hall and the living room, wandering back and forth in front of the piano. Today, the girl in the photo had long dark hair like Adeline’s. Her smile was small and demure, but there was something cocky about it. Something unnerving.

Adeline crossed to the window, but light coming in was dim and the curtains seemed too heavy to push aside. They wouldn’t budge. For the first time, she began to suspect that there really was nothing out there. That maybe there was nothing in the whole world but this curtained window, this apartment, and the sweet, smiling voice on the other end of the line.

“Aren’t you supposed to be in Spain?” she whispered, knowing that the question was pointless. There was no trip to Spain. There was no getting out. No going anywhere.

Daniele took another hitching breath and it dawned on Adeline that she was laughing. “You need to relax. Look, I have to go now. They’ll be opening the exhibit hall in a minute and I have to get my samples ready. Don’t you worry, though—we’re going to be fine. We’re going to sell the shit out of these matched separates, and then when that’s taken care of, I think we’ll move on to some of mydesigns.”

When the phone went dead, Adeline studied it awhile before setting it on the counter. She took off her shoes. She spent a long time sitting on the floor in the front hall, staring at the locked door. It was funny, the things that could exist, even in the smallest, darkest spaces. Funny, the things you believed in. That, for instance, you were a real, actual person with no shadowy corners, nothing left unknown.

After a long time, she got up and walked back through the bedroom closet into the little sewing room, with its swatches and scraps and stacks and stacks of butcher paper. The silks and leathers were gone now. The room was full of light tweeds and nice, soothing cottons. She was beginning to suspect that the smallness of the apartment was deceptive. With some work, she was reasonably sure that it would get bigger. Maybe she could even use this as an opportunity. A chance to work unfettered, perhaps to make something substantial—something great.

And yes, there was a small, secret part of her that looked at the closed front door and sighed in relief.

She had to admit, it was nice in here.

Photo by ally mcerlaine

Story originally posted June 6, 2011

At first it was little things—how he always wore the watch I’d given him, even though it left a raw spot on his wrist and he’d never worn one before.

I told myself that marriage really does change a person. But I think when people say that, they mean gradual change, like becoming more patient, and not that the person arbitrarily starts liking green beans. They mean little things, not whole personalities.

We’d been married for two years when I first started to feel like maybe I was living with a stranger. I shook it off until one evening when I was getting ready for bed and found myself remembering how Bradley had been pathologically unable to put his socks in the hamper and it used to drive me crazy. But he hadn’t left a single piece of laundry lying on the floor since the wedding.

The night I knew, really knew, we were staying up at a rental cabin with three other couples. (We’d become the kind of people who did things with other couples.) I knew something was wrong because he did the dishes after dinner and when we played dominoes and he won, he didn’t rub it in anyone’s face.

Later, I lay beside him in the dark, trying to decide what to do. He asked me if something was wrong, but I said no. Having a husband who picks up after himself and treats other people with consideration isn’t wrong, and I couldn’t tell whether I was awake or asleep.

We drove home the next morning without saying much. I was deep in a funk and he let me stay there. He bought me a cup of coffee and a danish without me having to ask. He didn’t try to make me talk to him.

Later, I locked myself the bedroom. I dug through his college footlocker and his dresser drawers, even though that’s not what trusting wives do.

It was in the back of the closet—this little wooden box tied with red string. There was a picture of me stuck to the top of box with Scotch tape, and the string was positioned directly over my eyes. When I undid the knot and the string fell away, I felt a curtain lift, like shaking off a cold fog. What had seemed like a long, confusing dream turned true and certain. It was clear, suddenly, like that knotted string had held my photo down, kept the doubts from surfacing, and now they were all floating there right in front of me.

The box was full of scraps and trinkets. The kind of things that wouldn’t mean anything if you weren’t already scared your husband was a very convincing fraud. There were burned matches and a baseball card and a lock of hair wrapped in satin ribbon and at the bottom, a little cloth doll made out of what looked like one of Bradley’s old T-shirt’s and tied up with twine.

When I went back out into the living room, Bradley was sitting in the couch, reading a copy of The Divine Comedy. For fun. The Bradley I’d gotten engaged to never did things like that.

“Who are you?” I said, standing over him. My voice sounded calm and polite. Vaguely interested.

He looked up at me, smiling cautiously, like I was trying to play a game with him and he didn’t quite know the rules. “I’m Bradley Walsh.”

And I started laughing.

For a second, he just sat there, holding the book. “Why is that funny?”

“Because you’re not.”

He didn’t answer right away. He just looked at me. Since the wedding, his eyes had become softer, more unguarded. Before, I’d always thought the new openness meant he’d discovered how much he loved me. That I had changed him. Now I was thinking that maybe he had just changed.

He set down the book and leaned forward, clasping his hands between his knees. “I’m Bradley. I’m your husband.”

“No, you’re not.”

He just looked up at me with a pained expression, like I was hurting his feelings.

“Who are you?” I said again. “Who are you really?”

For a second, I thought that he wasn’t going to tell me. He was going to say again that he was Bradley Walsh and then I wouldn’t argue. We would keep playing this game until we both forgot that’s what it was and we got old and died. But when you’re married to someone, you’re supposed to know their hopes and wishes, their secrets. When you’re married, you’re supposed to know exactly who the other person is.

He swallowed, unclasping and re-clasping his hands, but he didn’t look away. “I’m Alexander Boggs.” He said it like it was the most painful thing that had ever happened to him.

I stood looking down at him, holding the little T-shirt doll. Alexander had been Bradley’s next-door neighbor for the whole three years we’d dated, but I hadn’t seen him in forever. He’d moved right after the wedding and they’d fallen out of touch.

Alexander had been thin and weird and quiet. He’d been shy, too smart to fit in easily. The kind of person who would read The Divine Comedy for fun.

My legs felt heavy and useless and I sat down. “Why?” I said, crouched on the carpet with the doll in my hand. My voice sounded hoarse. “Why would you do something like that? How could you just do something like that?”

He sat on the edge of the couch, looking down at me—the sorriest, saddest look. “Because I loved you,” he said simply. “And you loved him.”

“Where’s Bradley?” I whispered. “Oh, God. Is he dead? Did you kill him?”

He half-rose, holding up his hands, shaking his head. “No, no, no—he’s not dead. He’s in Seattle.”

“Alexander moved to Seattle.”

“No—it’s like I told you. We … I switched us.”

I sat on the floor with my knees pulled up and my mouth open, remembering the last time I’d seen Alexander. It was two days before the wedding and I’d run into him at a bar downtown when I was out with my girlfriends. I’d been surprised to see him there. It didn’t seem like his kind of place. He’d cornered me out on the patio, telling me that Bradley wasn’t the person I thought he was, telling me not to go through with it, not to walk down the aisle. His voice was shaking and his eyes had been desperate in a way made me think that I’d never understood desperation before. I’d just assumed that he was drunk.

I nodded, twisting the doll in my hands and looking away. “He came to me, you know. On the patio at Lucy’s. He—I think he tried to tell me. He was a mess, practically begged me not to marry Bradley. He was almost incoherent. Why wouldn’t he at least try to tell me what had happened?”

On the couch, the man I married didn’t answer right away. For the first time in the two years since the wedding, he refused to look at me. “That was … before. Before the switch. That was me.”

I sat on the floor, clutching the doll, picking at its length of knotted twine. “What will happen if I untie this?”

When he did look at me, his eyes were pleading and Bradley had never, never looked at me like that—that deep, open look, like I was seeing him exposed and he was letting me, like I was seeing all of him, his darkest corners and his heart. He didn’t have to tell me what would happen. If I wanted Bradley back, I could have him.

Since the wedding, wristwatches and picked-up socks weren’t the only things that had changed. Kissing had gotten better. Movie nights and walks through the neighborhood and arguments and conversations had gotten better. Even sitting side by side on the couch together reading was better.

The doll was soft and small in my hand, uncommonly heavy. I held the length of twine between my thumb and forefinger, waiting to see if I would pull it.

Story originally posted May 2, 2011

Photo by Valentina F

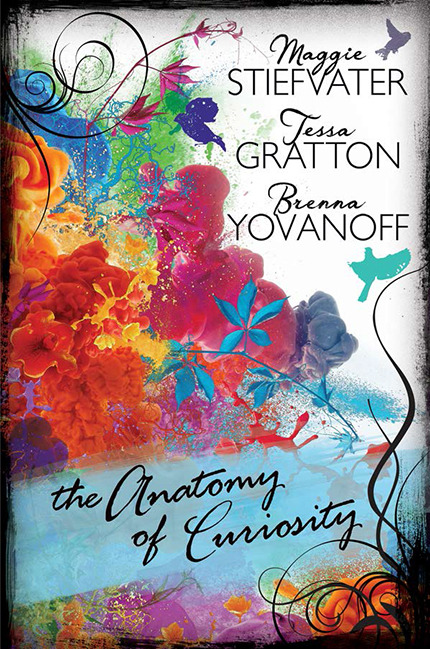

Today is the release date of The Anatomy of Curiosity.

I’m going to tell you a story about this book and how it nearly didn’t exist. It involves magic, blood, and friendship and is completely true.

Once upon a time, there were three friends, Brenna Yovanoff, Maggie Stiefvater, and Tessa Gratton, and they were witches.

No, I began that wrong.

Once upon a time, there were three friends, Brenna Yovanoff, Maggie Stiefvater, and Tessa Gratton, and they were writers.

They had been writers for as long as they could remember and friends for only a little less. The idea for the Anatomy of Curiosity — a show-and-tell writer’s guide for teen writers — was spurred years ago, when Tessa and Maggie were in the middle of an epic fight. The fight spanned states and months and involved battles with dragons in the Kansas sky, and it was mostly Maggie’s fault. I can say that, because I am Maggie.

Finally, when all parties were spent and bleeding out, the two witches reached over and clasped argument-bloodied hands.

“Let’s make a book together,” Maggie said. “That will fix all our problems.”

“You’re a problem,” Tessa replied, which meant yes.

And Brenna was tired of the bad weather, so she patted Maggie and Tessa’s heads and the book was born in the blood of friends. The problem with ideas made under duress, however, is that they are often incomplete, and the project fumbled and faltered even as the battle that spawned it was mostly forgotten. The thing that made the book the most interesting to us — that we were three different writers with three very different approaches to writing — was also what made developing a useful format impossible. How to balance teaching and entertainment? How to show three entirely different ways to get to a story?

By summer of 2014, we were on the verge of calling our agents and canceling it. It was a fraught summer anyway. The three of us were on a road trip — this was Maggie’s fault, and I can say that, because I am Maggie — in a sky blue ‘73 Camaro that was too small for three adults and too broken for a 7,000 mile road trip. Maggie didn’t believe in the concept of impossibility, though, and Brenna and Tessa believed in Maggie, so they were doing it anyway.

We were soaring across the Nevada desert when a raven flew over the top of the car. The Camaro’s engine bucked once. No, thought Maggie. We proceeded for several dozen more miles without incident, and then a second raven flew over the top of the car. The Camaro’s engine bucked again, and then it shuddered in a death rattle.

We coasted into Winnemucca, Nevada.

The car made it to the shade beneath the only tree growing in Winnemucca. We climbed into the bristling hot day and I threw open the hood. As I discovered that a single bolt had fallen from the alternator and stopped us, we heard a laugh. A third raven was sitting in the only tree growing in Winnemucca, Nevada, and it was laughing at us.

The bolt was gone, of course. It had probably fallen out on the highway back when the first raven had flipped us the bird.

We began to walk. It was over one hundred degrees. There was no one else in Winnemucca. They had probably all died. It was just us and the raven. We walked a mile to the closest auto parts store, where we bought a bolt and some lock nuts. On the way back, a Jack in the Box rippled into view. We recognized a mystical oasis when we saw one, so we entered and ordered drinks. As we melted, we talked Anatomy. This, we felt, was the moment of truth. We were stranded in Winnemucca, which might have not even been a real place, and it seemed like we might never escape if we didn’t solve the riddle. Did we choose to hurl ourselves against it one more time or did we choose to give up?

This is the release date of the book, so, spoiler.

We walked back to the Camaro, certain in our new plan. I put in the brand-new bolt and the Camaro started at once. The shade had moved from the only tree in Winnemucca and the raven was gone.

Fast forward to this fall. Tessa, Brenna, and Maggie are still friends, and still writers. The book is about to come out. I am in Virginia, states away from both of them, but I’m thinking about them. I have just come back from Colorado, where Brenna lives, and I have my eyes on my next trip to Kansas, where Tessa lives. I am rummaging in one of my backpacks for a hair band and my fingers touch something cold in the bottom. It’s heavy, and it’s cold, and it is not a hair band. I can’t imagine what it would be — this is just my tiny backpack that I carry clothing in for my overnight trips, and I had just emptied it the weekend before.

I take the object out.

It still had a little bit of rust on it. There was no raven around to laugh this time, so I did instead.

So we hope you enjoy the Anatomy of Curiosity. It’s got magic, blood, and friendship in it, and also some stories and advice.

You get to know the people who come in. If you spend long enough behind a counter, you get an idea of what they like, not just in their coffee, but of what makes them happy. You can look at someone once, and see all the commonplace joys and the tiny miseries that make up their lives. You learn to see these things, even when you don’t want to.

I was nineteen, working at Thatchman’s in the Village. Vietnam had ended, the horror was over, and there was still a giddy sense that we’d won—not Nixon, or the US Army, but we, the people. We had called for peace and they had heard us.

I’d done nothing.

Oh, I’d marched—I’d shouted and dyed my clothes and grown my hair like everyone else. But I hadn’t prevailed in any real sense.

I was at Columbia that year, studying comparative literature and 18th Century French poetry. If I’d done something remarkable, actually done something, I was certain that my life would have been fundamentally altered. The difference would be there on my skin, trembling in my voice, writ large on my face. My sense of justice would shine out my eyes. People would see my immutable strength of will, righteous and pure, like Joan of Arc.

Instead, I was just a girl in a cafe, pouring coffee and serving sandwiches, while out on Bleeker Street, the world went on and on in one long, greasy smear.

The man was older and always wore the same suit. Or maybe it was a different suit and he just had a lot of them. Either way, his clothing was conspicuous. No one else was wearing suits at all. He kept his hair shorter than the men who worked the docks and the warehouses, and much shorter than the men in the Village.

At first, I had a notion that he only came into Thatchman’s at all because of the dogs. There were two of them, black and gold, like Rottweilers. They were bigger than Rottweilers, though—massive through the shoulders and as high as my hip. Side by side, they padded after him. When he snapped his fingers, they sat. When he nodded, they got up and followed him.

On the first day he ever came in, it was raining. He walked in under the jangling bell, shook himself in a giant, glittering spray, and took off his hat. He was the kind of person wore a hat.

I was perched on the wooden bar stool behind the register, making notes in a history of the French Revolution.

At the counter he took a seat, winking in the most indecent way and leaning on his elbows. “Can I trouble you for a cup of coffee?”

His voice was low and rough, with a certain kind of accent. English, but not the bright, sophisticated kind from the movies. His coat was expensive, but the way he said his vowels was working-class.

“You’re not supposed to have dogs in here,” I said. “It’s against health code.”

That made him smile, and he gave me a sly, sideways look. “As dogs go, they’re uncommonly behaved. And Thatchman doesn’t mind. We’re old friends and he owes me a long list of favors.”

The pronouncement was less remarkable than you’d think. I didn’t know much about favors, but it was an open secret that in his early days, Joe Thatchman had been a bag man, cozier than cats with Don Vito and Tony Bender and the Genoveses. It was a dirty business, but business was good, although no one knew for sure just how much money had changed hands or how much goodwill it had bought him. Those days were long gone though. Thatchman had moved down to Florida a year ago and was easily in his seventies.

I poured the man his coffee and went back to marking up my book.

“La Terreur,” the man said after a while, glancing out at the rain and then smiling his sly smile. “Il pleut, il pleut, bergère, rentre tes blancs moutons.”

His French was bad, but he spoke it with a lack of hesitation that proved he knew the words, if not the finer points.

“I’m not a shepherdess,” I said, closing the book. I’d been underlining dates in an account of the execution of Fabre d’Églantine, who had gone to the guillotine singing verses from his own songs and distributing handwritten poems to the crowd. Singing the one about the shepherdess and the rain, but the man at the counter was sitting with his head bowed and I was holding the book so its spine faced him. He couldn’t have known.

He sipped his coffee, then made a steeple with his fingers. “And what would you rather be in this sorry life? A shepherdess, or a sheep.”

The question stung, though perhaps he didn’t mean it to. There were no shepherds, no one to tend the flocks, and I was beginning to lose faith in idealism, just like everybody else.

But still, a small, bright truth beat deep in my heart—that I would do it if I could. If I thought the act of doing it would matter.

I didn’t answer, but he kept smiling, like he knew what I was thinking. “What’s your name, shepherdess?”

“Claudette,” I said, and was startled to recognize that up until that moment, I’d been planning to lie, to say Marjorie or Carol or Betty. But his eyes were a dark, thunderous gray and I told him the truth.

After that, he came almost every morning, sweeping off his hat and bowing. He always said the same thing: “And how is the lovely Claudette today?”

And every time, I expected him to say My. How is my Claudette? But he only took off his hat and snapped his fingers and made the dogs sit obediently at his feet.

Out in the streets, the city still hummed and flickered, but the sense of passion—of power—was fading. Things were slowing. I could feel the energy draining away, bleeding out with every faltering beat.

The man with the dogs was constant, though. Through all the aimless noise and the indifference, he never changed. We talked together over the counter, drinking coffee. I read him Manon Lescaut, and the letters of Saint Augustine. He told me about the Middle East and the Congo, but he never told me his line of work. I liked it better that way. The child’s fantasy that his place in the world could still be something good.

“I was in the war,” he told me once, leaning on his elbows.

His eyes were paler than usual and I looked into them a long time, trying to see the villages burning, or the bodies, but there was nothing. His irises were strangely flat, without the splintered interruptions of filaments or striations.

I didn’t ask which war.

His mouth was close to mine, and he smelled like burned metal and oily smoke. I wanted to taste it, to lick it off his skin, but I just turned to the back counter and poured the coffee.

I had never been in love. At fourteen, I’d blushed giddily over Peter McCourdry who lived down the street. He was five years older, and when his mother got a telegram saying he’d been killed in Hue, I cried with the rest of the girls from my block, because it was a sad and ugly thing, but I didn’t feel the raw pain of heartbreak. I was crying because he was dead, not because I’d loved him.

He came in one day—my man with the dogs—smiling and whistling like always, but his eyes were sober.

“I’m not long for this city,” he said. “Autumn is come. My contract is up.”

“Let me send you off right,” I said before I could stop myself. “Come over and I’ll make you dinner.”

He shook his head, and in that moment, he suddenly looked so grave.

“We could meet at Alexander’s for a drink,” I said, horribly aware that I was starting to sound desperate. “It wouldn’t have to go anywhere. It wouldn’t have to be serious.”

He reached across the counter and took my hand. “Do you know what a brimstone dog is?”

In his eyes, I saw the bodies then. Not only the grisly casualties of land mines and napalm, but others. There were so many. I saw machetes. Axes, bayonets, hoes and rakes and sickles. I saw revolutions, howling mobs, all the things they tell you in history classes, but which never take on the staggering proportions of fact.

I shook my head and let him brush the back of my wrist with his thumb. His touch was warm, and I closed my eyes.

“A brimstone dog doesn’t rise above his station. He doesn’t own anything, he doesn’t want anything. His job is not to desire or to covet or to ask questions. He always does exactly as he’s told. Now look at me.”

His voice was harsh and I did it.

He leaned over the counter. His eyes were dark now, almost black, and I thought that he would kiss me, but he only bent his head to whisper in my ear. “A brimstone dog is no shepherd. His business is destruction, and he destroys the things he touches. But girls like the lovely Claudette have glorious years ahead. They have steadfast hearts and ferocious souls and true callings, and if they wish it, they have the inalienable right to try and save the world.”

And I nodded, knowing that this was the end. Without him, I would not be young, useless Claudette, always waiting. Righteous in only the stubbornest, most childish sense. Naive.

Knowing that in another greater way, it was the beginning.

He left with his dogs trailing after him, and I cried in the storeroom, harder than I had ever cried for anything. It was months before the jangle of the bell stopped sending my heart soaring frantically, cruelly, every time I heard it.

I thought I saw him once, years later. I was guest lecturing at NYU that spring, and had become all the things he’d talked about; activist, scholar, humanitarian—called to the proverbial carpet, in the thick of it, heart and soul. My hair was gray by then, and short.

I saw him across the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Bleeker, standing on a crowded corner with his dogs. The light changed and I stopped to watch as the rest of the city plunged on around me.

He did not look one second older than he had on the day he had promised me my future. He did not look like a man at all. His face was the calm, impassive face of some terrible storm. An engine of destruction, but in his way, he had created me.

The dogs of war were side by side, padding after him. It was raining.

Story originally posted September 14, 2009

Photo by roujo

I picked this as my very last story before The Anatomy of Curiosity comes out on Thursday because it’s one I can’t ever seem to leave alone—I just tinker and tinker with it forever. It was originally part of a common prompt where we each wrote a story about hell hounds. Also, as you can see? I tend to be kind of liberal in my interpretations of prompts. (And other things.) (Everything, really.)

My mother cut my heart out and put it in a box.

If this was a story, that’s how it would end.

It would begin with snow and the tragic, impersonal death of a young trophy wife, and fade into a montage of the replacement-bride, how she drenched her hair with honey and washed her face with milk.

That part’s true.

When my father remarried, the woman was unapologetically vain. She spent hours in front of the mirror, looking all alabaster and perfect. On Wednesdays and Saturdays, she went downtown to the day spa, where they shaped her fingernails and peeled the top layer of her skin off with various kinds of acid.

I stayed home and dyed my hair. I caked my face with powder and drew black lines around my eyes to show everyone the difference between us, that I wasn’t like her, that she wasn’t really my mother. She kept buying me dresses in pink and turquoise, and acting like we could be best friends.

Let me start again. My father’s wife had my heart cut out. She put it in a box.

The secret is that it wasn’t really my heart. Her slim gigolo boyfriend took me out to the Presidio, where the salt wind blew in off the sea. He touched my face and breathed licorice and aftershave on me, which made me want to scream. Then, he bought a pound of lamb’s heart from a butcher in Greek Town and took it home to her. He told her he loved her. He told her that the dense, membranous muscle belonged to me.

Okay, that last part was a lie. Can you tell that I’m lying? My stepmother doesn’t have a boyfriend. But if she did, he’d be young, with wavy hair and bad shoes. He’d be the kind of guy who knows where to buy organ meat in primarily-ethnic neighborhoods.

This is more like it: my obscenely vain stepmother put on her fifty-dollar Dior eyeshadow and her Manolo Blahnik pumps and reached for her Gaultier clutch. She cut her own heart out and dipped it in lead or mercury—one of those metals that poisons you and makes you go crazy. She fed it to me in sly, careful moments, in pieces, so that I would be like her.

I sat in my room with the shades pulled down and the venom of her heart moved like poison, getting under my skin and making me all drowsy. She spent hours by the country club pool, trying to look younger, but washed-up socialites never do.

I lay with the blankets over me, so heavy I couldn’t move my head. My dye-job was starting to grow out and the roots were showing. I stayed so long, it felt like I was turning into stone.

Then one night, she came to my room like a silent film-star, slightly crazed, smelling like gin, and yanked me out of bed. She sat me in front of the ruffled vanity, studying me with bleary eyes.

“I just want you to like me,” she said. “I just want us to do things together. Why don’t you like me?”

The whole time, she kept touching me in that clumsy, drunk way, tugging at my hair. I watched her reflection so I wouldn’t have to watch my own—the crumpled way her mouth seemed to just collapse. Her eyelids were dark and greasy-looking, like she’d bruised them.

She took me by the shoulders and shook me hard, suddenly. “Why are you doing this to yourself? Why do you insist on looking like a freak? Are you determined to embarrass me?”

She brandished a handkerchief—white, petal-soft—and began to scrub my face. She scrubbed hard and fierce, until my mouth got pink and so did my cheeks. She wiped my makeup off like she was scrubbing me back to life.

“Answer me,” she kept saying, but her voice sounded weird and shrill, and the words had stopped making sense.

When I opened my mouth, it felt like a tiny version of a black hole, where light disappeared and nothing could come out. She shook me and my head rocked back and forth. I couldn’t stop nodding.

She swept from the room without warning and came back with the scissors. I closed my eyes. The blades made a whispering noise, snick, snick. I felt lighter.

When she dropped the shears on the carpet, I didn’t know how to feel. It was the worst thing anyone had ever done to me. I had a sudden thought that no one had ever really done anything to me. It was glorious and shocking. I didn’t feel like myself, but for the first time in years, I didn’t feel like I was trying to be someone else.

In the mirror, my hair was brutally short. It stuck up everywhere, patchy-black in places, but most of it was blond. My mouth and cheeks were hectic, and my eyes looked wild. My blood felt like electricity. Like I could do anything.

We sat in front of the mirror, staring at my reflection. She was crying now, sloppy and horrifying, asking me to forgive her.

I wanted to tell her not to cry. That I forgave her for her smallness, for so many reasons.

I was something breathtaking and rare now, while she would never be beautiful again.

Story originally posted August 25, 2008

Photo by John Abella

For the stone-cold sum of five hundred dollars a week, Richard Casey hired me to watch him sleep.

I know what you’re thinking, but not every help-wanted ad ends in depravity. It wasn’t like that. When I called, the voice on the line sounded hoarse and exhausted. The listing wasn’t even in the kink section.

I was looking for placement as a personal assistant—making calls or taking dictation, arranging dentist appointments for old, rich men who can’t be bothered to buy their own socks or pick up their dry-cleaning. What I got was Richard.

He was tall and sullen, with three days of stubble and forty years worth of shadows under his eyes.

The first night, I brought a thermos of coffee and two sandwiches and a copy of Slaughterhouse-Five.

“What is that?” he said, staring at the book.

I gave him a long look. “An American classic.”

“Put it out on the steps and don’t bring it again.”

I did what he said because it was his show, and because I needed the money. I’d read it twice already, and anyway, there are all kinds of eccentricities you’ll put up with if you really need to get paid.

For six hours, I sat bolt upright on a hard kitchen chair, and he slept curled in the exact center of the bed, with his hands tucked against his chest and his pillow over his head, and I drank my gritty coffee with the sludge at the bottom and tried not to nod off.

Except, along about four o’clock, I started to hear small noises from the closet and from the space beneath the bed.

At first the sound was just a steady scraping—the scratch of a nib pen or a fingernail. But gradually, the noises got louder. When I knelt down to look, something moved far back in the shadows. Then it was gone.

In bed, Richard began to toss and mumble, tangled in the covers.

I stood up and kicked the footboard. “Hey, wake up.”

He gasped himself alert, looking wildly around the room, staring into all the corners. Then, with a glance at the closet, he sighed and let his shoulders slump.

“What was that under your bed? No, what the hell wasthat?”

He scrubbed a hand across his eyes, already right back to sullen. “Look, you might be here in a pretty strange capacity, but my personal life is none of your business. I don’t pay you to ask questions.”

“Itis my business,” I said. “It’s my business if you’re losing it, and it’s my business if all kinds of nasty crawlies want to come sneaking into your room, because either way, I’m the one who has to deal with it.”

Richard stared up at me. There were gray shadows under his cheekbones and he was grizzled and tragic, but not in the good way. There was nothing deep and brooding about his gaze. He just looked sick.

“Tell me, or I won’t come back.”

“I’m not a good man,” he said. And left it at that.

It was less than half an answer, but it was honest. He hadn’t bothered to lie, and that much I respected.

The next night, he was waiting for me with a basket of odds and ends. There was a bundle of dried sage tied with string, some candles and chalk and strike-anywhere matches. Sewing shears and salt.

“What is this?”

He set the basket beside the bed. “Consider them necessary objects. They might look harmless, but they’ll keep back the creatures of depravity.”

“Excuse me?”

“In my younger days, I ran with … a rough crowd. I mean a whole pack of less-than-savory associates. They did my dirty work, but now my time’s used up and the deal works both ways. Now they’re looking to collect on my debt.”

“Okay, I’m sorry, but are you out of your damn mind? Are you trying to tell me that you sold your soul?”

“I was young,” he said, with a shrug, like that meant anything. “I wanted insight and knowledge. I wanted to know that I wasn’t trivial, and I bought their service because I thought I could afford it.”

“So am I. Young, I mean. But I’m not about to lease myself a demon at a high interest rate and very little down.”

He climbed into bed and pulled the covers up. “Sometimes the long-term consequences don’t really hit you until later. I was in the market for a different kind of life, and they were offering.” Over the quilt, his grin was pale and empty like he was already dead.

So I took the basket and put it under my chair, and at two or three in the morning, the scratching started. This time, though, the sound was louder and more insistent and when the thing under the bed showed signs of getting a little too friendly with my feet, I reached for the necessary objects.

I sprinkled salt over my shoes and lit some tea candles. When I stuck the scissors point-down into the carpet, the scraping stopped.

“Very well,” said a low, soggy voice from the closet. “But tell me this, at least—why do you protect him?”

“Because it pays better than Kinko’s.”

“But the cost to your dignity, my dear! And where are your scruples? Do you know of his sordid past? Only look at his hands.”

In the bed, Richard sighed and rolled over, flinging out an arm. His hand was wet to the wrist with blood. It ran in sloppy rivulets and dripped down onto the carpet.

“I hope that’s metaphorical blood,” I said. “Because otherwise, it will be devilish hard to get out of the shag.”

“He gave us his eternal soul in return for wisdom, and then squandered that same wisdom in favor of power,” whispered a voice under the bed. “He gave himself over to vice and hedonism when it were better he craved knowledge. Even in retreat, he is despicable and clever. For a pittance a week, he owns you, and you accept that when you could surely rise above it.”

“And you figure you’ll snatch him away to hell because he had the audacity to live his own life instead of curing cancer and blessing lepers?”

“Hell has no circumference,” said the thing in the closet. “It is where we make it and this room is as good as another. Hell can be as vast as the sea, or as small as the head of a pin, but I promise you one thing: we will never let him sleep. Go back where you came from and leave us to our work.”

“What’s it worth to you? I mean, are you here for profit, or just for fun?”

“Is this the face?” whispered a voice from somewhere in the shadows. “The face that burned the topless towers of Ilium?”

“No,” I said. “But that sounds like a good time.”

“The power could be yours,” said the voice under the bed. “Imagine, all the cities of men—yours to own.”

“I wouldn’t give up my soul for that,” I said, thinking of home and bed and my book. “But I might could sell his.”

“Then let us have him, and we will give you New York and Chicago. We will give you London and Persia and Rome. Don’t you want Rome?”

“We don’t call it Persia these days.”

I stood up and kicked the salt off my shoes. I blew out the candles. I took away the scissors because people’s debts are their own and a job is only a good one until you find something better. Because I am not a good person, and that’s something I never lie about.

Story originally posted June 29, 2009

Photo by Steve Prakope

Rose hates the bougainvillea, which grows in wild sprays of red and purple, swarming over the railings and the walls. She hates the oleander, with its sweet-smelling flowers and its toxic sap.

She hates sightseers and tourists, weekend-giddy and winter-white. She even hates the hotel, although there’s nothing really terrible about it—after all, it’s just a hotel.

Mostly, she hates the fog, always forming beyond the breakers, always waiting.