#civil rights movement

Women’s History Month

Margaret Palm-African-American History-Civil War

Margaret Palm lived in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, along with 190 other free African-Americans, making up about 8% of the town’s population. She rented a white shack on the west end of Emmitsburg Road, and lived there with her husband, Alf Palm and their one child.

During the months leading up to the Battle of Gettysburg, African-American members of the Gettysburg community began fleeing their homes for fear that their freedom and safety would be in jeopardy, once the Confederate army invaded their little town.

There are many stories that surround the persona of “Mag Palm”, as she was called, some perhaps mere legends passed on by other civilians over the years. One legend refers to Mag as “Maggie Bluecoat”, referring to the story that she wore a blue coat of an officer of the War of 1812, and carried a musket while aiding other slaves in their fight for freedom from slavery.

One account, however, of an attempted kidnapping of Mag Palm by two local men is well known and well documented. Many free African-Americans were often victims of kidnapping by their own white neighbors, often to be sold off to Southerners for slavery.

Like the majority of African-American women in the Gettysburg community during the Civil War years, Mag made a hard living by scrubbing floors and washing the clothes of her white neighbors. One cold winter night in 1858, three years before the war even began, upon returning home from picking up her pay from one of her employers, Mag was attacked by two men who tried to tie her hands and take her away. . Mag managed to fight both men off with the help of another neighbor, John Karseen, a store owner in town, who witnessed the attack. Years later Mag Palm was photographed demonstrating how the men bound her hands and documented the attack for history.

During the battle, her home on Emmitsburg Road was occupied by the Union army and eventually destroyed in the fighting on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. Despite hardships in her own marriage, as her husband drank and was often prone to fits of rage, she managed to buy her own home again along Long Lane, a black community in the town, after the battle was finally over. She continued to struggle financially and was never able to stop beating rugs and scrubbing floors for a living.

Mag Palm passed away in October of 1896 from a heart ailment. She was buried in the Lincoln Cemetery in Gettysburg, among many other African-American civilians of the town. Her courageous story of struggle and survival is only one of the many forgotten African-American civilian stories of the women who lived and survived the battles fought right in their own communities, during the Civil War.

Remembering the amazing Harriet Tubman, who died on this day, March 10, 1913, in Auburn, New York.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was an author and abolitionist who wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin-Or, Life Among the Lowly”, in 1852. At the time, the book caused a sensation throughout the country, especially in the South. Stowe’s story opened up the country’s eyes to the hideous institution of slavery more than ever.

Stowe, the wife of the staunch abolitionist, Calvin Ellis Stowe, and an abolitionist herself, was once described by President Lincoln upon their meeting as “the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.”

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is considered the bestselling and most impactful book of the 19th century, and ranks second in Literature only to the Bible.

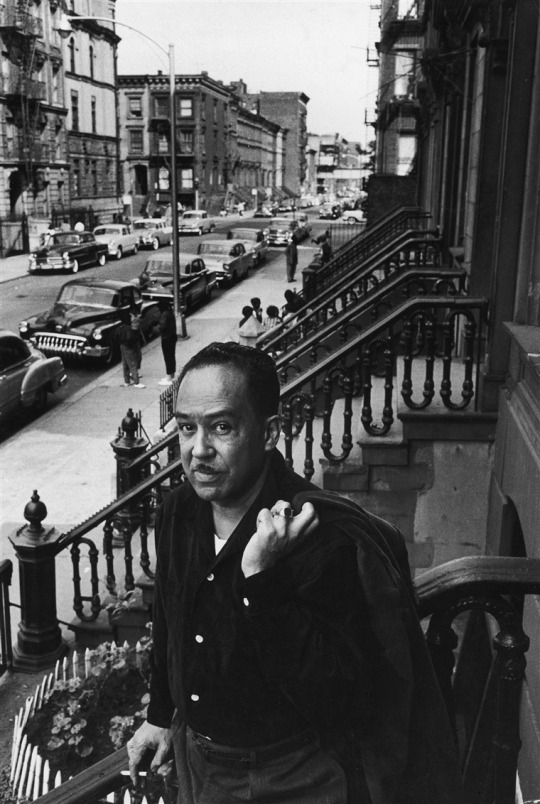

“The Weary Blues”-By Langston Hughes

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway….

He did a lazy sway…

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

He made that poor piano mean with melody.

O Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

Coming from a black man’s soul.

O Blues!

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan–

“Ain’t got nobody in all this world,

Ain’t got nobody but ma self.

I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’

And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more–

“I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied–

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.”

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The stars went out and so did the moon.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

He slept like a rock or a man’s that’s dead.

African-American soldier-Union Army-Civil War

Remembering John Lewis, born on this day, February 21, 1940.

“My Guilt”

My guilt is “slavery’s chains,” too long

the clang of iron falls down the years.

This brother’s sold, this sister’s gone,

is bitter wax, lining my ears.

My guilt made music with the tears.

My crime is “heroes, dead and gone,”

dead Vesey, Turner, Gabriel,

dead Malcolm, Marcus, Martin King,

They fought too hard, they loved too well.

My crime is I’m alive to tell.

My sin is “hanging from a tree,”

I do not scream, it makes me proud.

I take to dying like a man.

I do it to impress the crowd.

My sin lies in not screaming loud.

-Maya Angelou

“My People”

The night is beautiful,

So the faces of my people.

The stars are beautiful,

So the eyes of my people.

Beautiful, also, is the sun.

Beautiful, also, are the souls of my people.

–Langston Hughes

“This past, the Negro’s past, of rope, fire, torture, castration, infanticide, rape; death and humiliation: fear by day and night, fear as deep as the marrow of the bone; doubt that he was worthy of life, since everyone around him denied it; sorrow for his women, for his kinfolk, for his children, who needed his protection, and whom he could not protect; rage, hatred, and murder, hatred for white men so deep that it often turned against him and his own, and made all love, all trust, all joy impossible-this past, this endless struggle to achieve and reveal and confirm a human identity, human authority, yet contains, for all its horror, something very beautiful. I do not mean to be sentimental about suffering-enough is certainly as good as a feast-but people who cannot suffer can never grow up, can never discover who they are.”

–James Baldwin, “The Fire Next Time”, 1962