#duccio di buoninsegna

Triptych: the Crucifixion; the Redeemer With Angels; Saint Nicholas; Saint Gregory, (1311-18),Italy - Duccio di Buoninsegna

Post link

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART V: The Social and Material Contexts of Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna

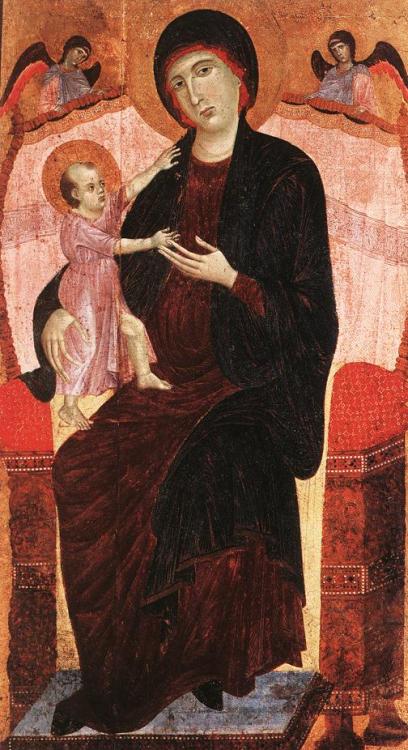

In 1285, the Florentine confraternity of the Laudesi comissioned the workshop of Duccio di Buoninsegna to paint an image of the Virgin and Child for the chapel they sponsored in the church of Santa Maria Novella. Like the other urban confraternities, the Laudesi provided care and services for each other at the time of a member’s demise, overseeing funeral rites, financially assisting surviving family members and collectively praying for the soul of the deceased. The latter took the form of laude, or hymns sung by the group in praise of the Virgin, begging her intercession on behalf of the defunct member. The lauds and other confraternity activities were performed in the group’s chapel, under the supervision of the Dominican friars. The panel painting of the Virgin and Child commissioned of Duccio was, therefore, was destined to serve as the visual focus of a devotional, musical performance by a prestigious, civic-minded group, conducted in a large stone-vaulted chapel.

In 1260, city-state of Siena defeated its long-standing rival Florence at the battle of Montaperti. This victory was attributed to the intervention of the Virgin, to whom the city of Siena had been dedicated the previous day. In the years following the battle, increased demand for representations of the Queen of the City caused Sienese artists to develop, elaborate and refine new Marian pictorial types and conventions. Thus, in 1285, Siena was where one went for high-quality, modern pictures of the Virgin by experienced artists, and Duccio was an established master painter of such images in that city. This fact must have complicated the prominent Florentine confraternity’s decision to choose Duccio over a local painter and indicates that the Sienese painter’s artistic reputation not only trumped even bitter, tenaciously-held political rivalries, but that it was more important to the Laudesi to have the best image of the Virgin available than it was to rehearse partisan loyalties.

The negotiations between artist and client are preserved in the contract, drawn up on 15 April 1285 and preserved in the archive at Santa Maria Novella. The contract stipulates that Duccio will paint an image in the Virgin and Child and angels on a panel previously prepared by a carpenter in return for the amount of 150 lire (approx. 91 florins). The confraternity had the right of refusal without payment “if the image did not please.” The contract does not specify anything about the style of painting, and no details of composition are mentioned, but it clearly enjoins the artist to use real gold for the background and genuine azzurro, the hugely expensive blue pigment made from ground lapis lazuli, for the large expanse of the Virgin’s robe. The expense of both materials was to be covered by the artist. The contract also states that the painting of the figures will be carried out by Duccio, and not by, one presumes, less-qualified workshop assistants. No delivery date is specified. Thus, at the level of the contract, what we think of as aesthetic issues are not mentioned at all. The value equivalent to 150 lire to be created by Duccio would lie in the conspicuous use of high-quality materials and the registration of the master’s hand in the work—preciousness and authority. These are the values one encounters again and again in medieval documents concerning the commission and/or evaluation of works of art, and they give us some sense of the period expectations viewers brought to the experience of looking at pictures.

TheRucellai Madonna is the largest 13th-century panel painting to survive.

The image of the Rucellai Madonna is accompanied by other pictures of the Virgin and Child by Duccio.

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART:

I: Saint Denis and Gothic Art

II: The Carolingian Renovatio

III: The Monastic Scriptorium

IV: Grisaille, or The Abstention from Color

V: The Social and Material Contexts of Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna

VI: Beauvais Cathedral and the Limits of Gothic Verticality

VII: The Harrowing of Hell

VIII: The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

IX: The Art of the Dark Ages

X: Simone Martini’s Saints

XI: Sainte-Foy de Conques

XII: The Cave Churches of Cappadocia

XIII: The Klosterneuburg Altar

Post link