#early flight

Fêtes D'Aviation. 1911. Goth.

47 ¼ x 63 in./120 x 160 cm

Practically the mirror image of Le Petit Parisien’s poster for the Paris-Madrid race, we are here offered the skyline of the small town of Le Puy. The text below advertises a rivalry between Jules Vedrines (who would become the first pilot to break 100 mph the following year) and the Peruvian Juan Bielovucic Cavalié (the second aviator to make it across the Alps).

Available at auction February 25, 2018.

Post link

Hello. We’ve been writing this blog every day for almost twelve months now. As it was our intention to find out why every single day of the year is BRILLIANT, we’re almost there and it seems appropriate to have some sort of countdown. If we make it, there will be seven more posts after this one. You can also find this blog on Wordpress, along with a short explanation of how it came about, and in which we reveal which of us has actually written all of this on the ’about’ page. Thank you all for reading, liking and re-posting. Will we reach a hundred followers my March 15th? Probably not…

Why March 8th is BRILLIANT

One Day I’ll Fly Away

Today is the birthday of Tito Livio Burattini, who was born at Agordo in northern Italy in 1617. Burattini explored and measured the inside of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the late 1630s with an English mathematician called John Greaves. But we don’t want to write about that today. He was also the first person to come up with the word metre for a standard unit of length. If your interested, it was first described as the length a pendulum needs to be to measure one second with each swing. But we don ’t want to go into any more detail about that either. We don’t even want to tell you about the time he was running a mint in Poland and got into trouble for adding glass to the coins. Today, we want to tell you about Burattini’s flying machine.

As we’ve spent the last two days banging on about seventeenth century authors who wrote about imaginary flying machines, we thought it would be nice to tell you about someone who properly had a go at building one. In the 1640s Burattini went to live in Poland, where he worked as architect for King Wladislaw IV. In 1647, he built a working model of a flying machine. It is generally described as a glider, but it appears to have had moving parts, so perhaps it was an Ornithopter, a machine with wings that flap like a bird. It was four or five feet long and could rise into the air carrying a cat as a passenger. History does not record how the cat felt about this. Pierre des Noyers, who was secretary to the Queen of Poland, said it remained airborne as long as a man kept the feathers and wheels in motion by way of a string. It was demonstrated before the Polish court at the request of the King. He must have been impressed because Burattini was granted money from the Royal Treasury to build a full sized model.

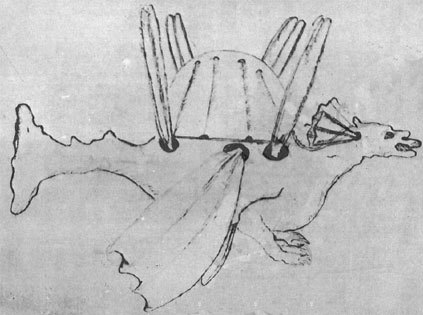

By May 1648, he had built his ‘Dragon Volant’ (Flying Dragon). Again, according to des Noyers, it had four pairs of wings. The two middle pairs seem to have been fixed and were for lift. The rear pair also provided lift but, along with the pair at the front, were designed to flap, by means of pulleys, and propel it forwards. It also had a large tail which moved in all directions for steering. The tail was also meant to act as a float, in case of emergency landing on water. The machine was designed to carry a crew of three. Two operating the wings at either end and a 'master of the ship’ in the middle. It also carried a large folding parachute in case the wings failed or they needed to slow its descent. Apparently, Burattini claimed that landing the craft would only cause the most minor of injuries, so that’s a comfort.

We are told that it was tested and did rise into the air, but was never completely successful. Burattini was convinced that it would work and that he would be able to use it to fly from Warsaw to Constantinople inside twelve hours, a distance of about a thousand miles. No one knows what happened to his machine. It may have been destroyed by the Swedes when they invaded Warsaw in 1655.

In our brief research today, we’ve actually found several attempts at human flight previous to Tito Livio Burattini. Mostly they end with someone simply falling off a tower or crashing through a roof. In 1540, there was João Torto, from Portugal. He made himself two large pairs of calico wings and also a helmet shaped like the head of an eagle. He crashed because the helmet slipped over his eyes. Some time in the sixteenth century, a French labourer built himself wings from two winnowing baskets and a coal shovel for a tail. He fell out of a pear tree into a drain. In 1600, there was Paolo Guidotti who built wings of whalebone, feathers and springs. He is reported to have flown a quarter of a mile before his arms grew tired. None of these people can really be described as having flown. They really only devised a means of falling more slowly. The first truly successful heavier than air flying machine would not be flown for over 150 years. It was built by someone who is, for us, a bit of a local boy as he was from Scarborough in North Yorkshire. He built a glider which he flew in 1804. He properly understood the principles of weight, lift, drag and thrust that you need to know about if you want to build an aircraft. He also knew the importance of cambered wings. His significance in the history of flight was acknowledged by the Wright brothers.

Post link