#engel v vitale

Stacey Chandler, Reference Archivist

In 1958, starting the school day with the Pledge of Allegiance was pretty routine for American kids. But mornings became a bit more complicated that year for students in New Hyde Park, New York, where the local public school board started requiring teachers to lead a class prayer (written by the state’s Board of Regents) after the Pledge each day. It didn’t take long for local dad Steven Engel and a few like-minded parents to challenge School Board President William Vitale on the prayer’s constitutionality, bringing the issue of school-sponsored prayer into the national spotlight and sparking controversy across the political spectrum.

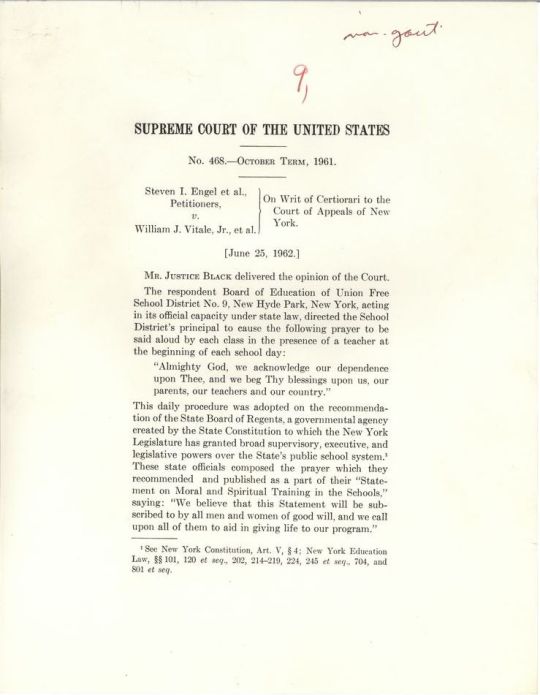

AsEngel v. Vitale made its way through New York’s courts, judges sided with Vitale and school prayer three times, stressing that students could leave the room if they didn’t want to participate. But on June 25, 1962, after hearings at the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Hugo Black delivered the 6-1 decision that reversed the lower court’s ruling and deemed school-sponsored prayer unconstitutional:

We think that by using its public school system to encourage recitation of the Regents’ prayer, the State of New York has adopted a practice wholly inconsistent with the Establishment Clause. …When the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief, the indirect coercive pressure upon religious minorities to conform to the prevailing officially approved religion is plain.

Though the ruling banned only official school-sponsored prayer and didn’t impact individual students’ rights to pray on school grounds, it motivated people across the United States to write to President John F. Kennedy with their thoughts about the role of prayer in public life. Their letters are now part of the archives at John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, where archivists are working on preserving and describing them.

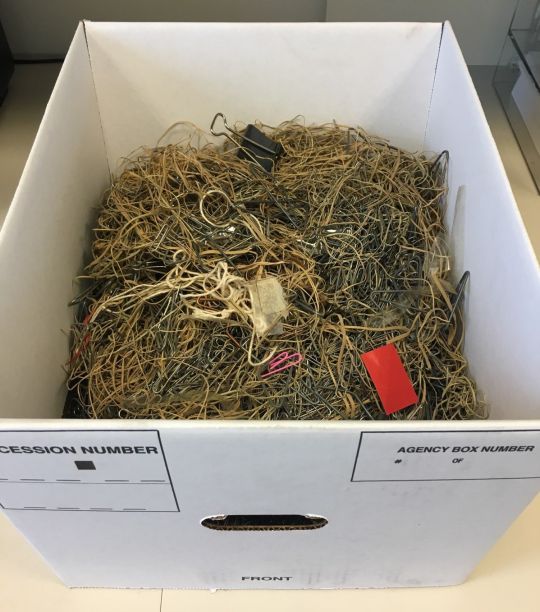

Damaging materials removed from the Public Opinion Mail collection during preservation.

In the two weeks after the decision, the White House Mail Room saw nearly 1,000 letters on the topic; only 13 of those, a staff member noticed, supported the Supreme Court’s ruling. Most writers brought up Communism or the Soviet Union, echoing the comments of politicians like Alvin O’Konski of Wisconsin, who suggested the Court was “doing everything possible to help Khrushchev bury us.” Meanwhile, children (often writing as part of a Sunday school class) worried they wouldn’t be allowed to pray in school at all.

JFKMPFPOM-1202-001

JFKWHCSF-0886-008

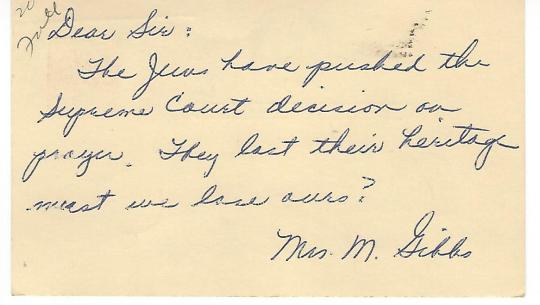

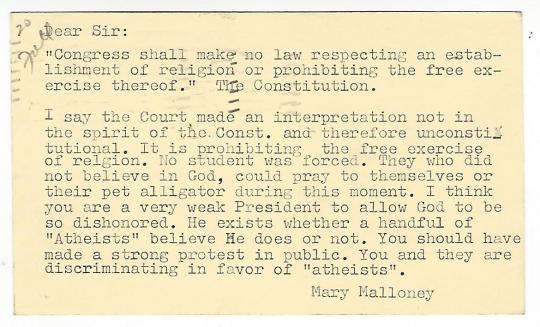

Others attacked the communities associated with the families involved in the case, who identified as atheist, Ethical Culturalist, Jewish, and Unitarian:

JFKMPFPOM-1202-002

JFKMPFPOM-1202-002

While the letters arrived, JFK was preparing for a previously-scheduled June 27 press conference. Expecting that he’d be asked about Engel v. Vitale, the President’s staff put together a few draft statements, including one that expressed sympathy with the dissenting opinion. But when a reporter asked “Can you give us your opinion of the decision itself?” JFK ditched the prepared remarks and said:

We have in this case a very easy remedy, and that is to pray ourselves. …I would hope that as a result of this decision that all American parents will intensify their efforts at home, and the rest of us will support the Constitution and the responsibility of the Supreme Court in interpreting it.

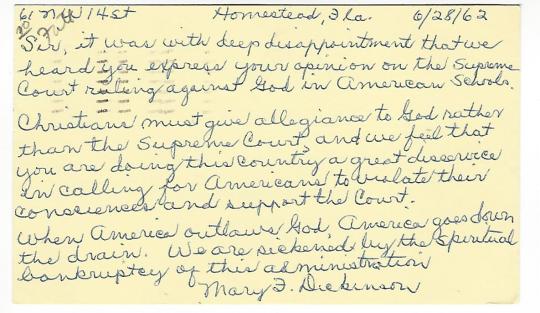

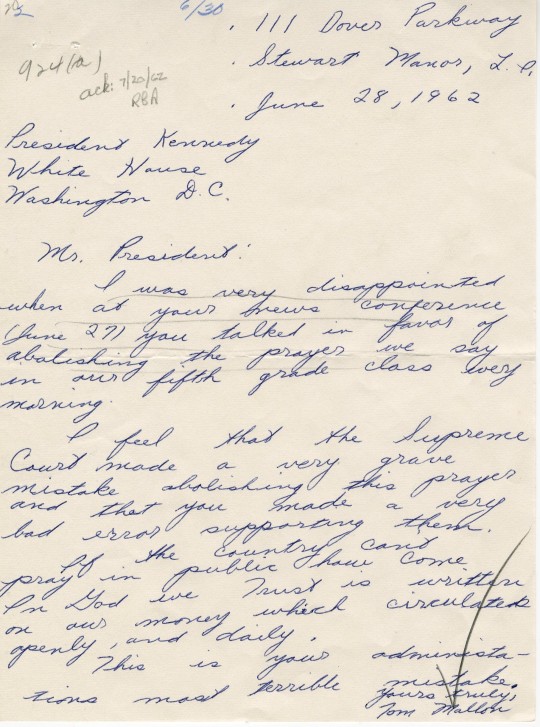

JFK’s comments sparked a second wave of letters, and most writers expressed concern over what they interpreted as outright support for the Court’s ruling.

JFKMPFPOM-1202-002

One of these writers was New York fifth-grader Tom Mallon, who later reflected that his own letter “based on a misapprehension (Kennedy was not supporting the Court’s decision per se), shows a stiff anger.”

JFKWHCNF-1709-007

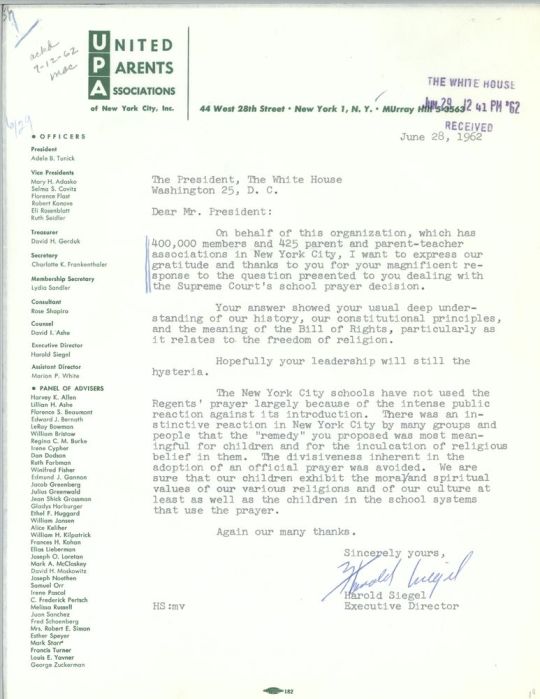

But not all of the letters about JFK’s comments were critical. Scattered throughout the boxes of mail on this topic are letters from leaders of organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the United Parents Association of New York City, who wrote in to express their approval of his remarks.

JFKWHCSF-0886-009

JFKWHCSF-0886-008

By the end of 1962, the flood of White House mail about the case was over – but the controversy wasn’t. In December (after receiving many constituent letters of their own), members of the House of Representatives voted to inscribe “In God We Trust” on the wall in the House Chamber, in what Congressman William Randall of Missouri called “our answer to the recent decision of the U.S. Supreme Court order banning the Regents’ prayer.” But even as the words were mounted on the Chamber wall, another landmark case was on its way to the Supreme Court – Abington School District v. Schempp – that would end Pennsylvania public schools’ required Bible readings in June 1963.

JFKWHP-ST-C7-2-63. John F. Kennedy delivers his State of the Union Address in January 1963 under the newly-installed “In God We Trust” inscription.

While a 1962 Gallup poll tells us that 79% of Americans approved of “religious observances in public schools,” polls can’t always reveal what’s hidden behind the numbers: the beliefs, attitudes, and understandings about an issue that contribute to each person’s opinion of it. Letters from the public can capture the perspectives that raw numbers can miss, and we’re working to preserve these materials for future study of decisions like Engel v. Vitale and their lasting impact on American politics and culture.