#public opinion mail

Stacey Chandler, Reference Archivist

In 1958, starting the school day with the Pledge of Allegiance was pretty routine for American kids. But mornings became a bit more complicated that year for students in New Hyde Park, New York, where the local public school board started requiring teachers to lead a class prayer (written by the state’s Board of Regents) after the Pledge each day. It didn’t take long for local dad Steven Engel and a few like-minded parents to challenge School Board President William Vitale on the prayer’s constitutionality, bringing the issue of school-sponsored prayer into the national spotlight and sparking controversy across the political spectrum.

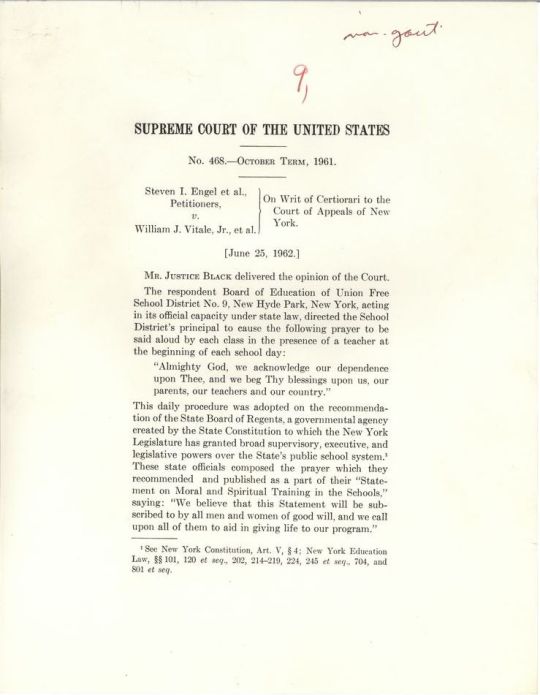

AsEngel v. Vitale made its way through New York’s courts, judges sided with Vitale and school prayer three times, stressing that students could leave the room if they didn’t want to participate. But on June 25, 1962, after hearings at the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Hugo Black delivered the 6-1 decision that reversed the lower court’s ruling and deemed school-sponsored prayer unconstitutional:

We think that by using its public school system to encourage recitation of the Regents’ prayer, the State of New York has adopted a practice wholly inconsistent with the Establishment Clause. …When the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief, the indirect coercive pressure upon religious minorities to conform to the prevailing officially approved religion is plain.

Though the ruling banned only official school-sponsored prayer and didn’t impact individual students’ rights to pray on school grounds, it motivated people across the United States to write to President John F. Kennedy with their thoughts about the role of prayer in public life. Their letters are now part of the archives at John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, where archivists are working on preserving and describing them.

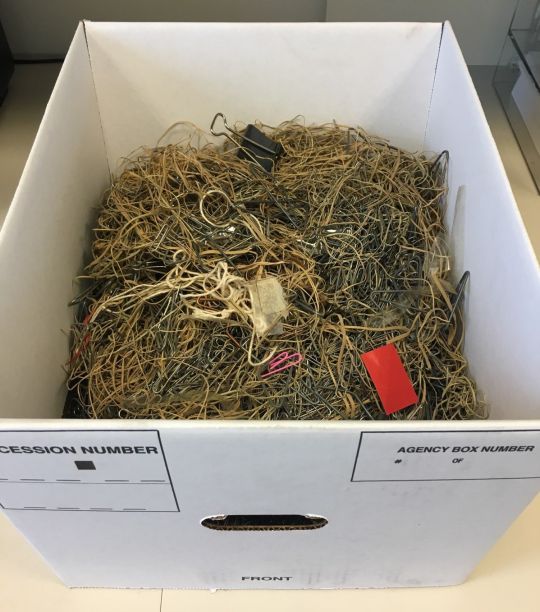

Damaging materials removed from the Public Opinion Mail collection during preservation.

In the two weeks after the decision, the White House Mail Room saw nearly 1,000 letters on the topic; only 13 of those, a staff member noticed, supported the Supreme Court’s ruling. Most writers brought up Communism or the Soviet Union, echoing the comments of politicians like Alvin O’Konski of Wisconsin, who suggested the Court was “doing everything possible to help Khrushchev bury us.” Meanwhile, children (often writing as part of a Sunday school class) worried they wouldn’t be allowed to pray in school at all.

JFKMPFPOM-1202-001

JFKWHCSF-0886-008

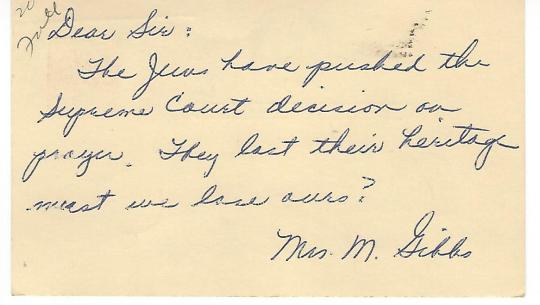

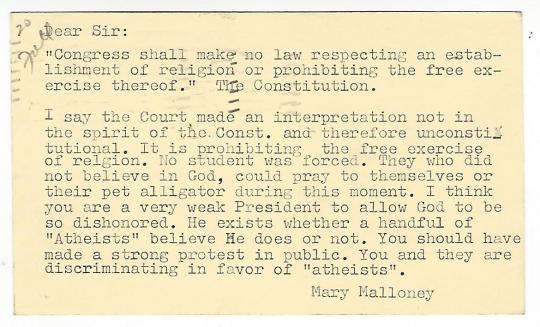

Others attacked the communities associated with the families involved in the case, who identified as atheist, Ethical Culturalist, Jewish, and Unitarian:

JFKMPFPOM-1202-002

JFKMPFPOM-1202-002

While the letters arrived, JFK was preparing for a previously-scheduled June 27 press conference. Expecting that he’d be asked about Engel v. Vitale, the President’s staff put together a few draft statements, including one that expressed sympathy with the dissenting opinion. But when a reporter asked “Can you give us your opinion of the decision itself?” JFK ditched the prepared remarks and said:

We have in this case a very easy remedy, and that is to pray ourselves. …I would hope that as a result of this decision that all American parents will intensify their efforts at home, and the rest of us will support the Constitution and the responsibility of the Supreme Court in interpreting it.

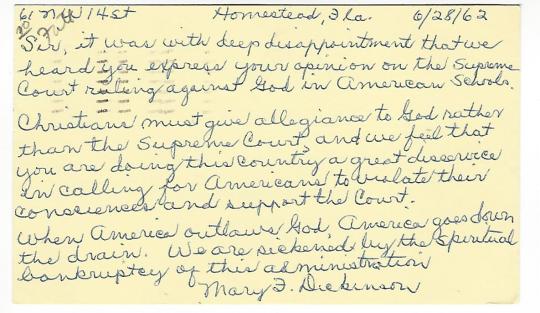

JFK’s comments sparked a second wave of letters, and most writers expressed concern over what they interpreted as outright support for the Court’s ruling.

JFKMPFPOM-1202-002

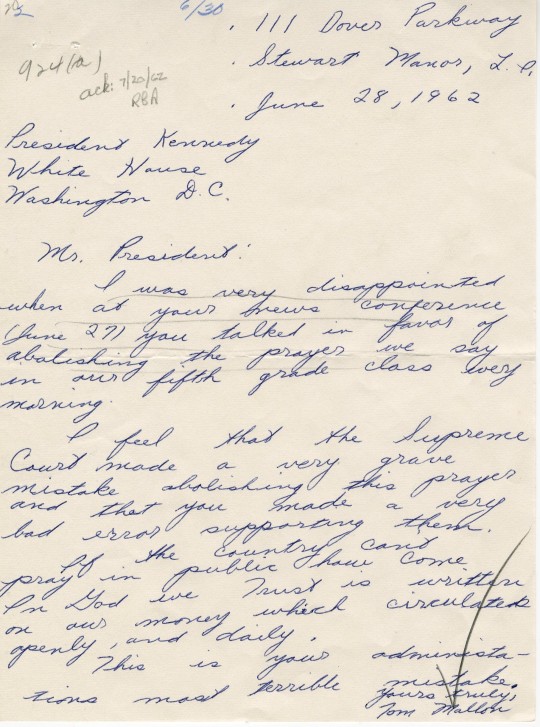

One of these writers was New York fifth-grader Tom Mallon, who later reflected that his own letter “based on a misapprehension (Kennedy was not supporting the Court’s decision per se), shows a stiff anger.”

JFKWHCNF-1709-007

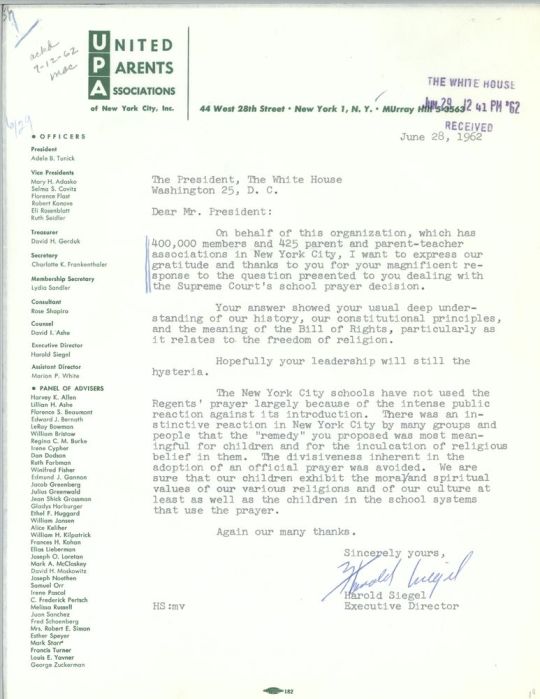

But not all of the letters about JFK’s comments were critical. Scattered throughout the boxes of mail on this topic are letters from leaders of organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the United Parents Association of New York City, who wrote in to express their approval of his remarks.

JFKWHCSF-0886-009

JFKWHCSF-0886-008

By the end of 1962, the flood of White House mail about the case was over – but the controversy wasn’t. In December (after receiving many constituent letters of their own), members of the House of Representatives voted to inscribe “In God We Trust” on the wall in the House Chamber, in what Congressman William Randall of Missouri called “our answer to the recent decision of the U.S. Supreme Court order banning the Regents’ prayer.” But even as the words were mounted on the Chamber wall, another landmark case was on its way to the Supreme Court – Abington School District v. Schempp – that would end Pennsylvania public schools’ required Bible readings in June 1963.

JFKWHP-ST-C7-2-63. John F. Kennedy delivers his State of the Union Address in January 1963 under the newly-installed “In God We Trust” inscription.

While a 1962 Gallup poll tells us that 79% of Americans approved of “religious observances in public schools,” polls can’t always reveal what’s hidden behind the numbers: the beliefs, attitudes, and understandings about an issue that contribute to each person’s opinion of it. Letters from the public can capture the perspectives that raw numbers can miss, and we’re working to preserve these materials for future study of decisions like Engel v. Vitale and their lasting impact on American politics and culture.

Emily Mathay and Stacey Chandler, Archives Reference

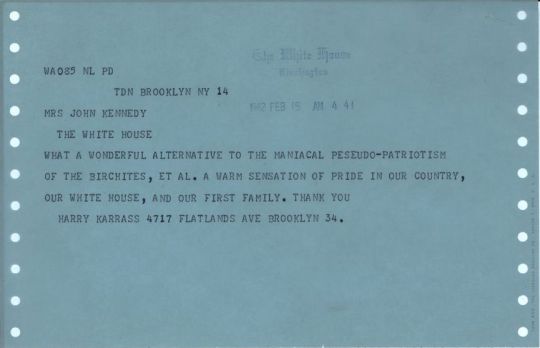

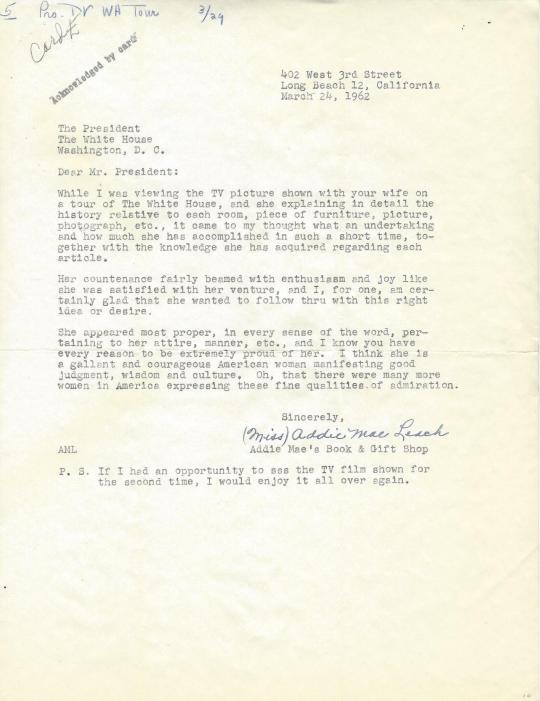

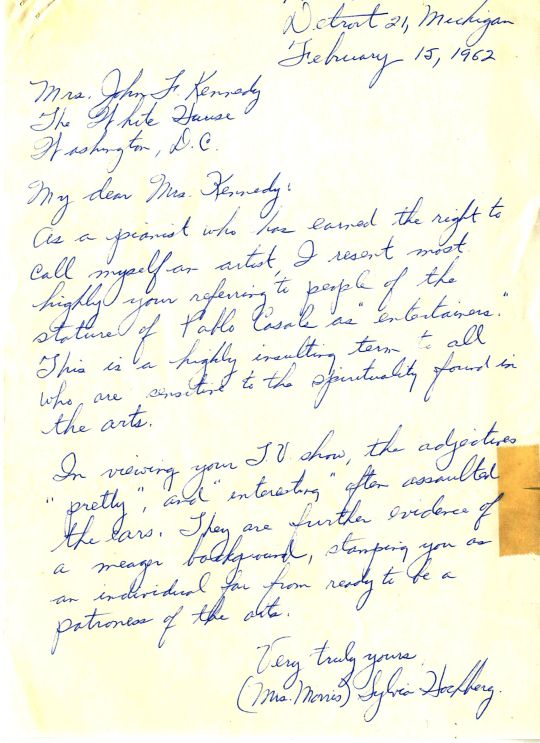

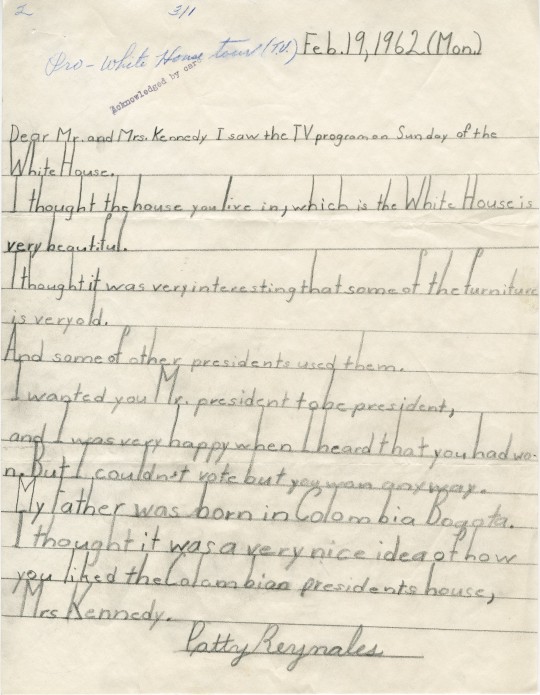

At 10 p.m. on February 14th, 1962, Jacqueline Kennedy brought millions of people into the country’s most famous house with her television special A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy. Hosted by the First Lady and CBS correspondent Charles Collingwood, the tour was the public’s first look at Jacqueline Kennedy’s famed White House restoration project. After the broadcast aired, thousands of people wrote to the White House with their opinions. Their letters are now in the archives at the JFK Library, where we’re working on preserving them.

A sampling of items archivists have removed from letters during preservation of the White House Public Opinion Mail.

By 1962, many Americans knew about Jacqueline Kennedy’s project to fill the White House with antiques from the time of its original construction; she had already helped create the White House Historical Association, the Fine Arts Committee, and the position of White House Curator. But her televised tour showcased the results of all that work for the first time, and invited the world to hear about the history she chose to preserve. The broadcast led many viewers to write to the White House with their own views about history – and the way political figures discussed it.

JBKOPP-SF002-005-p0013

JBKOPP-SF002-005-p0049

Most of the letters noted Jacqueline Kennedy’s appearance in some way, offering praise or criticism of her style, expressions, and tone of voice.

JFKWHMPFPOM-0659-005-p01

JBKOPP-SF002-005-p0104

Some messages offered thoughts (positive and negative) about the content of the tour itself, including personal connections to the history and art the First Lady talked about.

WHSF_947_22-p09

JFKWHMPFPOM-0658-005-p01

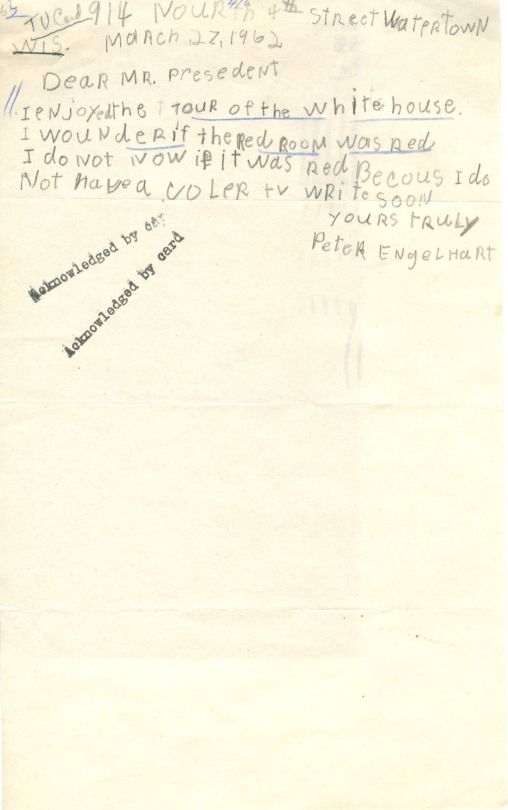

Others sent in clippings of positive reviews, requested for photographs of the First Family, or asked questions the tour hadn’t quite answered for them. A common question from kids who watched the black-and-white broadcast: are rooms like the Red Room really decorated in the colors they are named after?

JFKMPFPOM-0659-04-p18

Throughout the boxes of letters, one unexpected figure pops up: Astronaut John Glenn, who blasted into space in the Mercury capsule Friendship 7 just six days after the First Lady’s tour. Letters to the White House often comment on both the White House Tour and Glenn’s success, creating a documentary record of public reaction to both the intimate and the (quite literally) ‘out of this world.’

JFKMPFPOM-659-04-p10

A month after the broadcast, a new Nielson report noted that the number of White House visitors in the first week of March had increased by over 5,000 from the previous year. Though we can’t be sure that the dramatic uptick was a result of the First Lady’s broadcast, letters from the public reflect an overwhelmingly positive response to the preservation of the nation’s past even as it began to explore the new frontiers of the future.

JFKMPFPOM-659-02-p49

By Stacey Chandler, Archives Reference

On the morning of August 28, 1963, about 250,000 travelers came to Washington, DC for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the biggest civil rights rally of its time. These days, the March on Washington is remembered as a major milestone of the 20th century. But in 1963, Americans were divided about whether the March was a good idea at all.

ST-C278-2-63 (PX 96-33). Participants at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963.

A Gallup poll found that only 23% of Americans who’d heard of the March had a positive view of it - and the negativity didn’t come only from segregationists. President John F. Kennedy’s administration had recently drafted a new civil rights bill for Congress, and some civil rights activists worried that a big protest would push away representatives who were still on the fence about supporting it.

But while a record turnout was expected for the March, civil rights protests weren’t new to the American public in the Kennedy era – especially after a few very public showdowns between the White House and Southern governors. These and other events prompted people across the political spectrum to write to the White House with their views on American protest and civil rights activism. These public opinion letters are now part of the archives at the JFK Library, where we’re working on preserving and describing them.

JFKMPFPOF-0200-005-p04

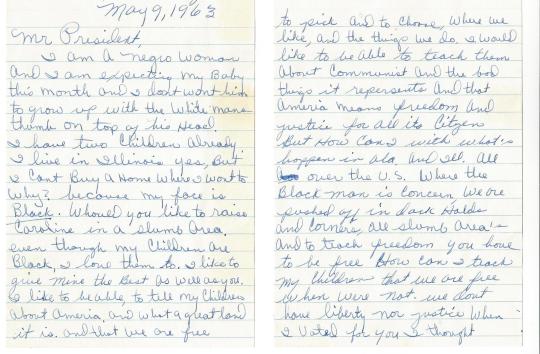

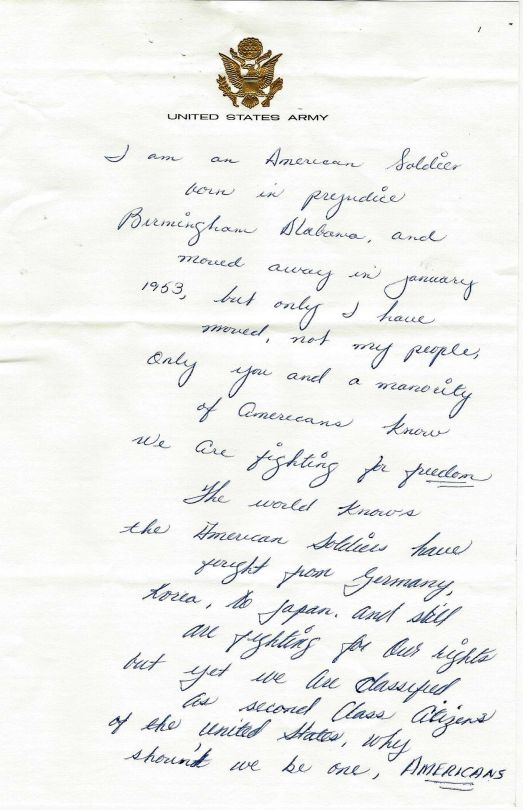

The first wave of letters about civil rights protests hit the White House in May 1963, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Birmingham Campaign” highlighted the violence that peaceful civil rights activists faced while trying to integrate the city of Birmingham, Alabama. Writers described the atrocities they read about in newspapers or, in some cases, experienced themselves.

JFKMPFPOF-0201-003-p01

JFKMPFPOF-0201-003-p03

JFKMPFPOM-0198-003-p03

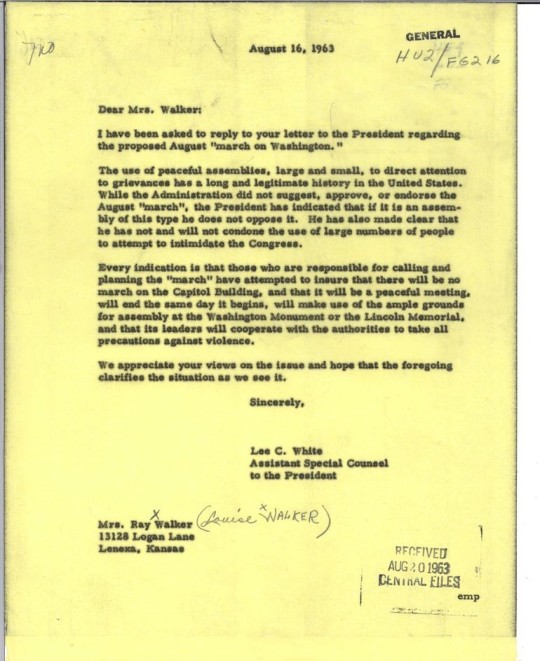

But as news about the proposed March on Washington spread in June and July, a reporter finally asked for JFK’s views about this specific protest at a July 17 press conference. The President defended the right to peacefully assemble, but stopped short of a full endorsement:

I think that the way that the Washington march is now developed…I think that is in the great tradition. I look forward to being here. …I would suggest that we exercise great care in protesting so that it doesn’t become riots, and, number two, that those people who have responsible positions in government and in business and in labor do something about the problem which leads to the demonstration.

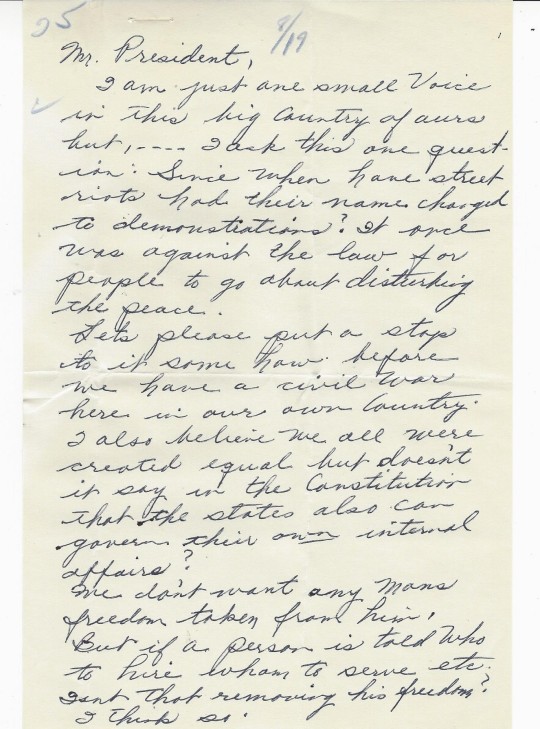

After these remarks, the White House saw an increase in letters about the March. Many interpreted JFK’s press conference statement as an outright endorsement, and the reactions varied widely.

JFKMPFPOF-0200-005-p03

JFKMPFPOF-0200-003-p03

Many of the anti-March letters expressed worry that the Civil Rights Movement was controlled by Communists, or predicted riots or violence.

JFKMPFPOM-0199-002-p02

Other writers took the opportunity to write in about civil rights in general, covering a wide range of opinions and beliefs.

JFKMPFPOM-0196-001-p01

JFKMPFPOF-0200-005-p02

Though our archives don’t include White House responses for all of these letters, a form response sent to multiple writers shows consistency with the President’s July statement: that the administration supported peaceful protest, but did not “suggest, approve, or endorse” the March itself.

JFKWHCSF-0365-008-p0266

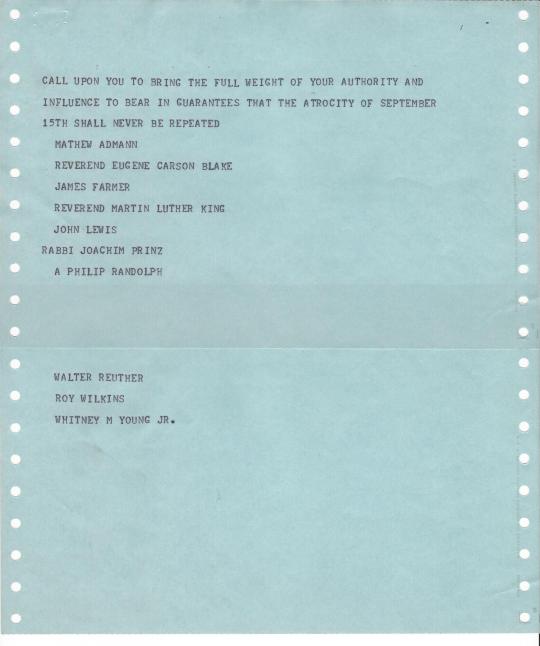

In the end, the March on Washington was a landmark achievement in the history of American protest, safely hosting more than double the number of marchers its organizers had planned for. National Urban League Director Whitney Young summed up the day in an interview after the March: “I just can’t see how anybody could have witnessed this today and denied something long overdue.” But only two weeks later, March leaders found themselves reunited via telegram – this time, to push the White House to action after a Ku Klux Klan bombing killed four little girls in the Birmingham Baptist Church basement. While the March was over, its organizers continued to assert that until the reasons behind it were resolved, the work wasn’t done.

JFKMPFPOM-0197-001