#female bildungsroman

• • • [spoilers below] • • •

In the middle of a blind date she doesn’t particularly want to be on, The Incredible Jessica James’ eponymous heroine squares off with her equally uncomfortable, male dinner friend/potential boyf/adversary.

They volley back and forth several brutally, “completely honest” questions.

After a few, he asks her, “How do you pay your rent?”

“I… work at a non-profit, in Hell’s Kitchen.” (Pride in her voice, though a somewhat knowing tone: yeah, I know. Very Brooklyn answer.) “I teach public school kids how to write and produce their own plays.”

“So… how do you pay your rent?”

She laughs.

Already – my Netflix ticker says this is barely 13:50 into the entire movie – the two biggest threads of the film come together: (1) an endearing, realistic romantic comedy starring Jessica Williams (that Dope QueenoffThe Daily Show who now does other stuff – namely, this) and rom-com’s staple dorky everyman Chris O’Dowd (because the thinking, even semi-straight woman[**] needs an IT guy); and (2) the female Bildungsroman.

If you’ve taken an English class any time since approx. 1980, you’ve probably had to learn and use “Bildungsroman” in an essay. It’s the coming-of-age novel, the story of growing up, an arc from innocence to experience. Except, as a pivotal cohort of feminist critics in the 1980s argued, the female Bildungsroman means “growing down,” a story of women being taught by society: Lower Your Expectations! Conform! Settle! The debate around what even isa Bildungsroman has wrestled with how gender-specific a story about maturing and (in essence) #adulting can be, given that women in Western society since the inception of the novel itself haven’t really had the options to leave home, discover themselves as autonomous, free, independent selves. The male Bildungsroman, in other words, is about the boy who grows up to be a man, and gets a job; the female Bildungsroman is about the girl who becomes a lady, and finds the right husband. Sure, there’s status and some freedom attached to that – class status and thus economic freedom, as the bourgieness of the novel excels at rewarding. But by and large, no matter how failed the male career, no matter how much the woman takes on a new career of domestic labor, the novels usually emphasize along these lines. Men achieve professional success; women aren’t left to be spinsters.

(A professor in my department, Jesse Rosenthal, pointed out how pervasive this narrative still is within even the most indie, “unconventional” of tales. His case study? (500) Days of Summer. As he recounted to a class on the 19th-cen. British novel, here’s a movie putatively about the romantic maturation of the male subject – a rom-com trajectory usually reserved for women [i.e.. He’s Just Not That Into You could never be She’s Just Not That Into You]. But Joseph Gordon Levitt’s problematic-nice-guy fairy tale, complete with problematic-indie-dream-girl Zooey Deschanel, isn’t his acceptance of a limited role in his next relationship. It’s a successful job interview. [roll credits])

So the fact that The Incredible Jessica James coupled, in several senses, these two plots wasn’t surprising to me. Less than 15 minutes in, and yeah, obviously, Chris O’Dowd is gonna get the girl, and Jessica is gonna get over her ex by realizing that she “deserves” this more mature guy. Her work is great and all, the story goes, but obviously what we want is Bridesmaids with a lady of color. Comedy + late capitalism’s precarity (Jessica, how doyou pay your rent? Are you going to have to go live with your parents like Kristin Wiig had to after the cupcake biz tanked?) = love story. And bonus points for being about Instagram, and having a WOC lead where a white actress would have been five or ten years ago (slash even now): kudos, my friends. Kudos.

But… that’s not what happened. And here’s where this movie is radical.

BecauseThe Incredible Jessica James is a female Bildungsroman [or Bildungs-Film] that subtly, cannily, definitively breaks the mold.

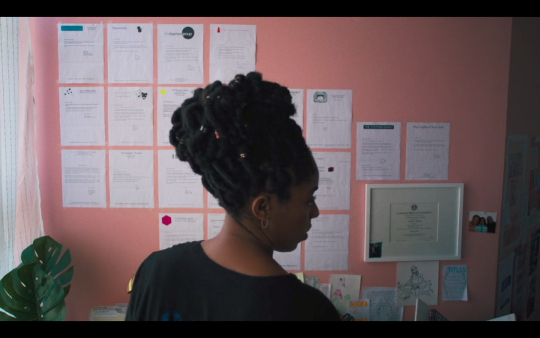

It isn’t a story about a woman realizing how wrong she is to be hung up on the wrong, bad boy, and thus the return to the family, to society’s right side of the tracks, to *herself* that is made whole again by giving up her rebellious adolescent wandering and waffling. Instead, TIJJpresents a heroine who goes through a series of rejections not of lovers, but of jobs [displayed on her wall: see first screencap]. It tracks her indefatigable efforts to make what she loves (theater) into a career, even a somewhat uncertain one. It’s about her slow realization – not the sudden “awakening” narrative that critics have ascribed to female/feminist Bildungsroman of old – that what she’s doing, working every day with kids, continuing to send out her resume, writing and reading and connecting with the public circles of her aspiring field – all that, isa career.

Take, for example, a crucial marker of James’s acceptance of herself, and of her status, as grown-up, matured, sufficiently adult that she’s no longer faking it til she makes it: she’s Made It. The blueish-purple jumpsuit spotted in a Brooklyn consignment shop, the kind that is explicitly labeled as male by the sewn patch of its previous owner, “Randolph,” tall enough for even the pretty tall JJ.

Working-class, second hand, male-identified uniform; natural hair in box braids; red lipstick and bright eyeliner. This is how Jessica meets her parents. But the music slides to an uncomfortable stop as Jessica gets off the Arrivals moving walkway: her parents are bourgie, sweet, stable, and utterly unlike her in spirit. This is the American middle-class dream – as authors from Frantz Fanon to Paul Gilroy to Ta Nehisi-Coates have written – that preys on Black people specifically, the double-consciousness of passing as it works in all its formulaic vapidity. Jessica’s younger sister, too, has bought into this dream: she takes one look at Jessica.

“You look like an auto-mechanic,” Jerusa (her sister) points out in a tone dripping with judgment.

“It’s cool, though, right?” Jessica beams.

“Yeah…” her sister nods, meaning the opposite. “I mean, you’re not going to wear it to the party?” [Her very normative, unironic, and uncritical baby shower.]

“… Nope,” Jessica deflates. Pretending this has been her plan all along.

Because this family isn’t ever going to be the place where Jessica can be anything other than stifled. The prim-and-proper group sits in the suburban family room late that night, merrily gooey-eyed over a romantic drama they’re watching on TV, whose dialogue (that’s all we overhear) is so utterly, sickeningly banal that Jessica doesn’t even enter the room. She hangs back, in the darkness. The entire setting – with all its race and class implications (and the sincere and moving subplot about the James family’s struggles with making their own rent, and how this continues to the present with Jessica’s public school kid whose divorced parents are fighting over custody, intertwines class and race throughout) – requires, in sum, the painful subjugation of Jessica’s self. A “growing down,” a compromise, as its definition of “growing up.”

Women of traditional Bildungsromane, Abel, Hirsch and Langland posit, “are not free to explore; more frequently, they merely exchange one domestic sphere for another. While the young hero roams through the city, the young heroine strolls down the country lane” (8).

Jessica James, by contrast, goes back to New York.

And back, at least superficially, to the romantic sphere of this rom-com. Where her jumpsuit is acceptable; where people like her appreciate thoughtful, empowering arts (instead of, like her mom’s Very White Book Club Lady friend wants, Cats). Where her lesbian best friend (that actress from Master of None) is the elective community James wants, not the family she’s contractually obliged to recognize in her blood. Where Chris O’Dowd is; where her career is.

So how does the movie wrap up the romantic plot without making this aboutJessica’s successful “deserving” of the Right Man™?

(It’s worth noting, before we spoil the ending, that the Boone – aka O’Dowd – subplot of the movie focuses on his not being able to get over the right girl. He stalks his ex-wife, amusingly because it’s Chris O’Dowd, but I think the movie implies cringe-worthily and creepily too: the dude side of rom-coms, it seems, is bleak; not somewhere the film is especially interested in lingering, and neither really are we. He’s eventually ashamed of himself, and this humility is deliberately more endearing than his Every Breath You Take enactment was. Admittedly, we could get into the politics of who says they’re sorry at various points in the film, who asks for and who gives forgiveness, and the ways in which being placed in a position of forgiving is, in a way, simultaneously powerful and powerless. But Nietzsche and feminism is a debate for another time.)

What I’m especially struck by – and I’ve watched this movie myself and with my sister, and then thought about it again after it was praised by another woman I love who watched it an ocean away – is that TIJJends with Jessica.

The final two scenes are crucial here. The penultimate brings together the two guys; formally, the two choices of a Bildungsroman: forward, or back? Jessica’s ex, Damon, finds her backstage after the kids’ theater night concludes, and opens with how he “know[s] how much this means to” her. For a split second, I panicked: OH GOD, fuck, this is why we can’t have nice things. They’re gonna have this guy realize how great she is – because obviously the only way a guy can appreciate a woman is for him to be in competition with another man. She deserves better! I shouted internally. Don’t take him back: sure, you realized you were as responsible for the break-up as he was. So what! You can do better.

But they hug, they sigh, and he leaves. (At which point I breathed a sigh of relief.)

Enter Chris O’Dowd. (At which point I was back to, fuck conventionality. What a missed opportunity.)

Turns out, though, the movie saw me – and the Bildungsroman – coming a mile off.

Because Jessica – unlike Rachel – gets on the damn plane.

Jessica, after all, has been offered a huge job opportunity in the most novelistic of cities: London. But things are just getting back on track with Right Guy; but going is her dream, is her big break; but he, like Damon, just realized how great she is – he read her entire corpus of theatrical writing, and declared – #honesty – that he’s still coming to grips with her complexity, on the page and off; but; but; but…

But… she forgot to tell him about London. And in a sense, this is where swelling crescendos of orchestral joy began filling my head, because if this had been a rom-com like the others, if this had been a female coming-of-age story like the others, she would never forgotten about him. Ever. Not once. He would have been her one phone call; her best friend-par-excellence; her Person. Instead, that honor goes to Tasha, the semi-parodic self-involved best friend who always, though, has Jessica’s back.

And so when the clearly wealthy – loaded, because of an app that is explicitly about the formal gesture afforded by technology of Family, without the actual emotional or affective labor of having to talk to those totally different people who somehow raised you! – Boone mentions “frequent flyer miles,” we can anticipate an airplane that Jessica (by now we can say, of course) will be on.

“Just if you wanted to… bring someone with you… to show you around the town,” he hedges, just before the cut.

“How does that work? […] Frequent flyer miles?”

Cut to Jessica – in the god. damn. JUMPSUIT. Pleased as punch, sitting in – oh yes, we can have nice things – not even economy seats. The nice seats.

At which point, the truly INCREDIBLE part of this movie becomes clear:

Tasha: Dude, I can’t believe your boyfriend bought us tickets to London.

Jessica: Okay, who said anything about him being my boyfriend?

T: Wait. What are you talking about? This is like, the most romantic gesture I have ever seen.

JJ: Yeah, it’s dope. But it takes more than a couple of roundtrip tickets to London for somebody to be my boyf.

T: That is so boss.

Shandra – the elementary school girl whose divorced parents prompted Jessica’s own reflection on her parents/childhood – returning to her seat: What is so boss?

T: Uh, Jessica.

S: Oh, yeah. Duh.[… I]t was really cool of your boyfriend to get me a ticket, too.

T: Hey, whoa, whoa, whoa. Sister. Just because a guy buys a lady a couple of roundtrip tickets to London does not make him her boyfriend.…

[a beat]

S: You know, I like your jumpsuit.

JJ: Thank you. Yeah, it’s pretty bad-ass, right?

S: Hm. Yeah, it is.

They all exchange smiles, the camera zooms in for one final-close up of Jessica’s excited anticipation of landing for the beginning of – not her romance, but – her career.

COME ON! You’re telling me the final scene of this movie is a new affinity, a new definition of family, in which the white, straight, married couple form is reshaped into the female solidarity of friendship, while the child of that hetero dyad of yore is now the dark-skinned girl who herself is a budding author, having been mentored by Jessica, who is – onscreen – mentored by another strong, Black female playwright??? You’re telling me that throw-away moment in the corridor backstage with Chris O’Dowd that seems like the lead-in to a kiss is in fact his last appearance onscreen??? You’re telling me the movie, moreover, goes out of its way to stress – TWICE – that whatever erotic/romantic relationship they’re in, Jessica didn’t accept this trip as the quid pro quo of settling down??? YOU’RE TELLING ME THIS NEW COLLECTIVE IS SO AWARE OF ITS MEMBERS’ QUIRKS AND FOIBLES AND SELF-AUTHORSHIP/FASHIONING THAT THE FINAL LINES OF THE MOVIE UNDERSCORE THAT JESSICA CAN, IN FACT, DRESS HOWEVER THE FUCK SHE WANTS, AND THAT SOME PEOPLE WILL LOVE HER FOR IT, AND FEEL THE SAME ABOUT THE THINGS SHE LOVES???

Get out of my face, TIJJ. You have *EXPLODED* the female Bildungsroman, and maybe the Bildungsroman full-stop. There is no return to the original society, no compromise, no settling. Jessica isn’t the one forced to the margins of the story by choosing either independence or submission: the family is.

For that matter, romance sort of is. Jessica has no “boyf”; Tasha has no (onscreen, stable, couple-form) gf, but neither is she a hypersexualized lerb. She masturbates on/off-screen, but it’s one of her quirks! She and Jessica go to a lesbian bar, where Tasha chats with several recognizably-styled queer ladies: but she is neither reduced to her own romance plot, nor denied any sexuality at all. She and Jessica, however queerly you read their relationship (and I don’t especially, but I see how one could), are the empowering couple of the film, supporting each other not just in romance but in their mutually-reinforcing careers.

This is a rom-com about aiming high, about finding a career not in, because of, or in spite of a guy, but because it’s the one through-line of the entire story. Jessica begins and ends loving her work, and the slow build of that love rewards her by the end. She has Made It. The fact that she probably goes home to an attractive dude who boosts but is not himself responsible for her career – sure, he gets her upgraded tickets, but her confidence, “forthright[ness],” and drive suggest she would have made it to London without him, no question, by whatever means necessary – is icing on the cake. Yes, there was a maturation narrative within the romantic plot (she learned to leap in her relationships; she also learned, as Boone did, to have realistic expectations of where both partners are at any given moment in a relationship). But this, the movie stresses, is not the end of the story. It’s a subplot within herstory.

[gif from x]

I don’t think it’s unimportant, either, that Jessica Williams – a fine actress in this movie, entirely winning the screen – plays the heroine. By which I mean, I think it’s all the more radical that to play the romantic interest to gaze adoringly at rom-com’s Irish nerdboy Chris O’Dowd, the director/producers/writers picked a woman whose best-known appearances are in scathing condemnations of male privilege,white supremacy, and American patriarchal, racist, and just terrible norms in general. That such a woman is the new face – but I didn’t even get to talk about the fact that in a few scenes, Jessica J/W’s complexion is a little spotty, which made me (with a long history of struggling with the medical and psychological reality of being a teenager and then adult woman with terrible acne) want to cry with gratitude: this is what a heroine looks like?

Sure, Wonder Woman is fab, but damn I needed this representation so much – maybe more – than the superheroic, impervious demi-goddess from Themyscira. I needed a strong, self-loving, no-nonsense, tall, Black, not-quite-starving artist in Brooklyn, jamming with headphones in the concrete stairwell of her building, who proudly declares, “I’m freakin’ DOPE.”

I needed a new female coming-of-age story – especiallyin 2017 –, and, somewhat subtly but unquestionably, The Incredible Jessica James delivered.

***

{** I use “women,” “men,” “male,” and “female” throughout this piece to refer mostly to the historical categories of those identities/concepts. I also want to be clear that I’m not trying to gloss over this film’s missteps; rather, I’m trying to celebrate its major, but possibly missable, wins. Lastly, I know that in German Bildungsromanmeans *novel* of development/maturation, not *film*. Don’t @ me.

Thanks to Jesse Rosenthal (JHU) for getting me thinking about the basic understanding of the Bildungsroman in such concise, formal terms. For the debate about male vs./and female Bildungsromane, see – to name just some –, Abel, Hirsch and Langland (eds.), The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development (1983); Lorna Ellis, Appearing to Diminish: Female Development and the BritishBildungsroman, 1750-1850 (1999); Rita Felski, Beyond Feminist Aesthetics: Feminist Literature and Social Change(1989);Franco Moretti, The Way of the World: The Bildungsroman in European Culture (1987); and Susan Fraiman, Unbecoming Women: British Women Writers and the Novel of Development (1993).

The Incredible Jessica James (2017), dir. and writer Jim Strouse; produced by Beachside Films/Netflix. S/o to casting, Kate Geller and Jessica Kelly. Thanks also to Springfield! Springfield! movie scripts for their transcription, which saved me time. }