#jesuisahmed

What do we mean when we say “freedom of speech”?

full article here: http://www.worldbulletin.net/world/152585/charlie-hebdo-fired-cartoonist-for-anti-semitism-in-2009

Post link

This weeks attacks at the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris have justly sparked a lot of public discussion about terrorism. Unfortunately, most of it has been trite, relying on the old narrative of barbarians at the gates of civilization.

The proverbial “they” are the terrorists, constructed in the collective imagination out of fear, ignorance, and gullibility. “They” hate our perceived freedoms. Our movies have been saturated with images of them: brown-skinned men and women attacking our way of life. Tabloids prominently display their faces alongside images of carnage. Such an understanding lacks nuance and ignores historical, social, and cultural context – it creates a caricature of culture that constructs a monolith of Otherness that must be destroyed at all costs in order to preserve Western liberalism.

We in the West live with an inflated sense of our importance and with a mythological understanding of our society. In the United States, this myth takes the form of American Exceptionalism. It’s the same myth that Reagan perpetuated when he paraphrased the Puritan leader John Winthrop, invoking the “shining city on a hill.” It’s this belief that was echoed by American diplomat Richard Guenther and later quoted by Teddy Roosevelt when he proclaimed “We will fight for America whenever necessary. America, first, last, and all the time. America against Germany, America against the world; America, right or wrong; always America.”

The European face of cultural superiority is not very different. In a telling post-9/11 quote, then Italian Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi said “We should be conscious of the superiority of our civilization, which consists of a value system that has given people widespread prosperity in those countries that embrace it, and guarantees respect for human rights and religion. This respect certainly does not exist in the Islamic countries.” It is this same sense of cultural superiority that Winston Churchill betrayed when discussing the Palestinian issue, “I do not admit that the dog in the manger has the final right to the manger, even though he may have lain there for a very long time…I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia…I do not think the Red Indians had any right to say, ‘The American Continent belongs to us and we are not going to have any of these European settlers coming in here’. They had not the right, nor had they the power.”

So pervasive is this myth that it infects all facets of our culture. Westerners trace their political fantasies to Athens and Rome, fetishizing democracy and republics that were inherently flawed, corrupt, and unequal. More important than who the West identifies as its cultural ancestors, is who or what the West denies. The West is not, in its eyes, barbarous, savage, and cruel. The West is not corrupt, dictatorial, and problematic. The West is justice and all those who oppose it are the purveyors of evil and injustice. Instances that say otherwise, are mere aberrations in our history, not symptoms of our inherent cultural defects. It was Western culture that birthed the Nazi party, it was Western culture that birthed the Spanish inquisition, it was Western culture that both developed and used nuclear warfare. At a point, the weight of all these aberrations becomes too great; there are simply too many Wounded Knees, too many internment camps, too many My Lai massacres, too much slavery, too many secret medical tests on Black people, too many Hiroshimas (it takes a kind of savagery of the soul to eradicate a people without even looking at them), too many drones in the sky, too many Fergusons, too many Eric Garners, too much torture.

The West is more than the United States. Our notions of France are archetypal of our ideas of Westernism. Paris is the “City of Light” and we claim the French Enlightenment ushered in a new era in human history that emphasized reason over traditional, light over dark. The slogan of the French Revolution translates to liberty, equality, and fraternity - a three word summary of what we imagine the West to stand for.

Yet, it was the French who colonized much of North Africa, namely Algeria and Tunisia. The colonized were oppressed both in their native lands and as immigrants in France. France’s history in Africa, rife with racism, is especially problematic. The French referred to the colonized who took on French customs as “evolved,” implying an empirical superiority over native culture. During the Algerian War of Independence, an uncounted number of Algerian Muslim protesters were massacred by the police in the streets of Paris.

When the scales of justice are weighed down with these so-called aberrations, justice, like a house of cards, falls over, an aberration unto itself.

America and the West is not devoid of problems, we are hardly exceptional in that way.

When a terrorist attacks a civilian or government target in a Western country, the discourse varies based on the attacker. If the attacker is obviously Muslim, the agent is labeled an Islamic terrorist. If the attacker is a white Westerner, he is deranged and irrational. One is a product of his society, the other is not. This essentialist dichotomy is precisely the reason the media was slow to label the Tsarnaev brothers attack in Boston, so much so that they threw one of the brothers on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine.

But when either terrorism is discussed, societal, economic and political context is dismissed. The personal context of the white American terrorist is magnified - he is a deranged man, a disturbed lone wolf acting outside the bounds of his society. The Muslim is essentialized as culturally-predisposed to terror by a violent faith, acting in accordance with the nature of his society.

Think on Timothy McVeigh, the man convicted and executed for the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995: he was portrayed as alienated, insane, and fundamentally evil. The social and material conditions that produce McVeighs are rarely explored; rather, psychological defects are cited as the root cause of their malice. We have had similar homegrown American terrorists. We have had Ted Kaczynski the Unabomber, a Harvard-educated mathematician who wrote scathing critiques of modern industrial society. We have had the shooters: James Holmes in Aurora; Michael Page, the Army Veteran responsible for the Sikh temple shooting; Jared Loughner the Tucson, Arizona shooter; and Steven Kazmierczak, who killed 27 people in a Northern Illinois University lecture hall. These are just a few of the many. Between 1982 and 2012, there have been at least 62 mass shootings in the United States. Most of these acts were meant to send a political or social message.

Is it something about our society or culture that produced these killers? Are they anomalies or are they representative of something ubiquitous?

Simultaneously, there are no close studies of the Muslim individuals who perpetrate acts of terror. Their upbringings are not dissected nor are their conditions examined; instead they are painted with a broad brush. Their childhood friends are not interviewed, elaborate psychological profiles are not publicly discussed. The motives are reduced to one word: Islam.

If the target of both kinds of terrorists is the Western power structure, in the eyes of the media, the West is a priori exonerated without scrutiny. No reasonable person would blame the terror on people shopping in a Parisian kosher market or those working in the Twin Towers. Clearly, the victims of terror are innocent.

Our current discussions on terrorism are inadequate. They are largely racist, serving to further the political and economic interests of the Western power structures while doing nothing to create a world in which we can live alongside one another.

Responsible discourse lies not in dismissing these actions as the products of either psychosis or an evil, inferior culture. It begins with self reflection– in unraveling our myths about others and ourselves.

On January 7th 2015, three gunmen entered the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine, and opened fire, killing 12 people and injuring 11 more. The assailants targeted the magazine, particularly its cartoonists, as retribution for cartoons and artwork that they deemed offensive to Islam. Entering the office, they identified their targets and unleashed a barrage of bullets.

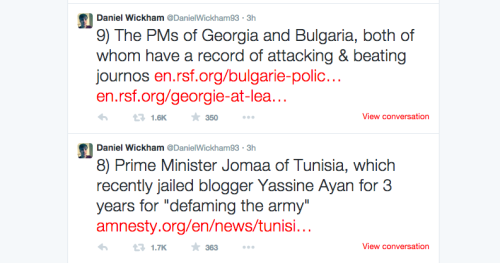

The subsequent public reaction to the attack has been of understandable horror. As expected, right wing news outlets relied on the simplistic narrative of Islam as a religion of terror. Social media quickly erupted to denounce the attacks; #JeSuisCharlie became a trending topic on Twitter, Tumblr, and Facebook.

The sentiments behind this hashtag are noble and reasonable, as lives were taken and freedom of speech was assaulted. Journalists, actors, government officials, and religious leaders the world over have shown solidarity.

French President Francois Hollande described the attack as one “of exceptional barbarity,”while the US President called the attacks “cowardly” and “evil.”

But I cannot #JeSuisCharlie. Not because I don’t condemn the ghastly murders. I do. Not because I don’t believe in freedom of speech. I believe it is the bedrock of a truly free and civil society. I cannot for other, larger, reasons.

I cannot #JeSuisCharlie because attacks of this nature are not commonplace in the West, yet they have been part of a dark and ugly reality in much of what we broadly call the Muslim world for years.

Where is our hashtag for that?

In Pakistan alone, over a thousand civilians are killed by terrorism every year. The numbers have almost steadily escalated every year since the so-called War on Terror began, with about 140 fatalities in 2003 and almost 1800 in 2014. In 2013, an especially brutal year, the number of civilian fatalities was around 3000. But the terror doesn’t come from Al-Qaeda and like groups only. A lot of it comes from us.

(table from Institute For Conflict Management)

Where is our hashtag when the United States blows up a wedding convoy or a 16-year-old American-born teenager in Yemen? When it launches a missile into Momina Bibi, a 67-year-old Pakistani grandmother going about her gardening? They stood for something greater than freedom of expression: the freedom to exist.

I cannot #JeSuisCharlie, because we’ve always mourned the deaths of Europeans and Americans. We’ve purported to launch wars for them. But if we value lives, then where is our indignation for deaths in the Muslim world?

Statistically speaking, a terror attack will kill a few Pakistanis this week. A drone strike is likely to kill a civilian in Pakistan, Yemen, or Somalia soon.

Where are their hashtags?