#john stuart mill

I am not aware that any community has a right to force another to be civilized.

John Stuart Mill

Post link

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty

Sure, you could pay to read the New York Times, or take an extra minute out of your day to blow through their paywall, but for free[*] you could be getting the good information about John Stuart Mill that was just dropped at johnpistelli.com. There’s plenty of nuance in his almost legalistic prose, I promise you, as he heroically tried to synthesize the Enlightenment with Romanticism. An excerpt from my new essay:

How is the infrastructure of free speech to be erected and sustained? Through a proper education, one in which students are allowed to hear a diversity of views from those who hold them. Citing precedents in intellectual history from the Platonic dialogues (in which philosophy is conducted as an argument between multiple personae) to the legal practice of Cicero (who learned the opposing counsel’s case better than his own) to the process of Catholic canonization (which invites the “devil’s advocate” to speak against the candidate for sainthood), Mill argues that students must be prepared to defend their own positions against counterarguments they themselves are able to reconstruct from the inside: “He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that.” Otherwise, people will hold even their own opinions lazily, unfeelingly, and without really knowing why—a state of intellectual torpor that bodes ill for the polity.

Precisely the situation in which once-august and now-bathetic institutions like the Times sadly find themselves.

I don’t even know why I started reading or rereading On Liberty the other day, nor do I remember if I’d ever read the whole thing before or just excerpts in college. I do remember reading all of The Subjection of Women in a Western Civ class, and then answering a final essay exam question in the same class where I was invited to imagine and write out a debate between Mill and Hitler. I recall having some fun with the stage directions: “Mill lifts both eyebrows in startled alarm” and the like. The professor would no doubt be fired today.

Anyway, I think I went back to Mill because George Bernard Shaw had me wanting to revisit the Victorian sages (and indeed to expand my knowledge of some of them beyond the Norton Anthology)—nothing to do with the news. But current hegemonic left-liberalism has of course abandoned Mill’s liberal ideal of free speech without even seeming to understand its rationale—they appear as well to be in the process of abandoning any theory of mind whatever, ironically returning to a fully infantile state—so On Liberty remains pertinent.

Two things I didn’t get to discuss in my essay since I try to keep these things short enough for Goodreads:

1. Mill was a Malthusian who thought the state should seize control of breeding. He disfavored “a woman’s right to choose,” to use an obsolete phrase from my youth, to opposite effect as does the religious right today: he might not outlaw but mandate abortion, for generally eugenic reasons. This seems to me inconsistent with the broad principles of On Liberty and premised on a flawed and zero-sum idea of humanity’s relationship to nature and economics.

2. I quoted but did not elaborate on Mill’s beguiling sentence, “It may be better to be a John Knox than an Alcibiades, but it is better to be a Pericles than either.” I first encountered it before I ever read any Mill at all as the epigraph to James Wood’s paralyzingly eloquent essay against Thomas More, “A Man for One Season.” Wood’s idea is that More was no better than Knox, a religious sectarian, and therefore not a fit Periclean hero for a liberal, secular society. But is it really better to be John Knox than Alcibiades? It’s a case of two extremes, an unenviable choice. I confess I haven’t read any Thucydides since my first year of college, but I do recollect that Athens’s golden boy (and Socrates’s boy-toy) was an unreliable man, to say the least. Still, would I want to found Scottish Presbyterianism or hang out with Socrates? I swing sexually the other direction, but Al seems to have enjoyed primarily female company anyway, among all his wild and dangerous political intrigues. Wherever you come down, it’s certainly a thought-provoking sentence.

_________________________________

[*] While I have been “playing real good for free,” like the “one-man band by the quick-lunch stand” in the Joni-Mitchell-via-Lana-del-Rey ballad, if you like it and if you’re able, you might please send moneyorbuy a book to keep the operations ongoing. Thank you!

Post link

If the cultivation of the understanding consists in one thing more than in another, it is surely in learning the grounds of one’s own opinions. Whatever people believe, on subjects on which it is of the first importance to believe rightly, they ought to be able to defend against at least the common objections. But, some one may say, “Let them be taught the grounds of their opinions. It does not follow that opinions must be merely parroted because they are never heard controverted. Persons who learn geometry do not simply commit the theorems to memory, but understand and learn likewise the demonstrations; and it would be absurd to say that they remain ignorant of the grounds of geometrical truths, because they never hear any one deny, and attempt to disprove them.” Undoubtedly: and such teaching suffices on a subject like mathematics, where there is nothing at all to be said on the wrong side of the question. The peculiarity of the evidence of mathematical truths is, that all the argument is on one side. There are no objections, and no answers to objections. But on every subject on which difference of opinion is possible, the truth depends on a balance to be struck between two sets of conflicting reasons. Even in natural philosophy, there is always some other explanation possible of the same facts; some geocentric theory instead of heliocentric, some phlogiston instead of oxygen; and it has to be shown why that other theory cannot be the true one: and until this is shown, and until we know how it is shown, we do not understand the grounds of our opinion. But when we turn to subjects infinitely more complicated, to morals, religion, politics, social relations, and the business of life, three-fourths of the arguments for every disputed opinion consist in dispelling the appearances which favour some opinion different from it. The greatest orator, save one, of antiquity, has left it on record that he always studied his adversary’s case with as great, if not with still greater, intensity than even his own. What Cicero practised as the means of forensic success, requires to be imitated by all who study any subject in order to arrive at the truth. He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. The rational position for him would be suspension of judgment, and unless he contents himself with that, he is either led by authority, or adopts, like the generality of the world, the side to which he feels most inclination. Nor is it enough that he should hear the arguments of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. That is not the way to do justice to the arguments, or bring them into real contact with his own mind. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them; who defend them in earnest, and do their very utmost for them. He must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form; he must feel the whole force of the difficulty which the true view of the subject has to encounter and dispose of; else he will never really possess himself of the portion of truth which meets and removes that difficulty. Ninety-nine in a hundred of what are called educated men are in this condition; even of those who can argue fluently for their opinions. Their conclusion may be true, but it might be false for anything they know: they have never thrown themselves into the mental position of those who think differently from them, and considered what such persons may have to say; and consequently they do not, in any proper sense of the word, know the doctrine which they themselves profess.

—John Stuart Mill, On Liberty(1859)

My “female-bodied” Catholic school teachers, lay and religious, most of them daughters of the immigrant working class, who marched on Washington every January 22 and had us write our congressional representatives once or twice a year protesting abortion, send their regards. They certainly thought it was an ethical question—and, since these are not mutually exclusive categories, a political one too, hence their petitioning the state. I am in the end as much the student of John Stuart Mill as of them, civil libertarian in inclination and by conviction, so my politics are not theirs; but I will not do them the injustice of denying them a coherent ethics. They believed they were defending souls. And there was and remains something sublime in this belief, even for those of us who don’t share it. Just because you will not deign to understand their ethics, it only shows that you, for all your honors and your erudition, have been easily outsmarted by a group of elementary school teachers to whom, in the guise of championing the female and otherwise marginalized intellect, you baselessly condescend.

Post link

—John Stuart Mill, On Liberty(1859)

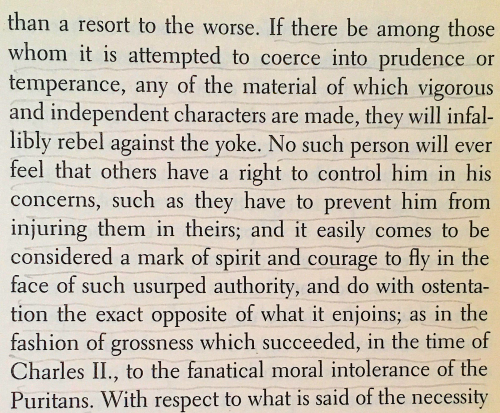

Mill explains the vibe shift and/or new conservatism and/or post-left and/or new right. Even his 17th-century example is libertine vaguely/crypto-Catholic right-wingers reacting against left-wing puritan Protestants.

Post link