#john wilmot

John Wilmot 2nd Earl of Rochester, poet, libertine and member of Charles II “Merry Gang” died on this day in 1680 aged just 33.

Post link

Image of Rochester from ‘The works of the Earls of Rochester, Roscommon, and Dorset, the Dukes of Devonshire, Buckinghamshire etc., with memoirs of their lives’

Post link

Love bade me hope, and I obeyed;

Phyllis continued still unkind:

Then you may e'en despair, he said,

In vain I strive to change her mind.

Honour’s got in, and keeps her heart,

Durst he but venture once abroad,

In my own right I’d take your part,

And show myself the mightier God.

This huffing Honour domineers

In breasts alone where he has place:

But if true generous Love apppears,

The hector dares not show his face.

Let me still languish and complain,

Be most unhumanly denied:

I have some pleasure in my pain,

She can have none with all her pride.

I fall a sacrifice to Love,

She lives a wretch for Honour’s sake;

Whose tyrant does most cruel prove,

The difference is not hard to make.

Consider real Honour then,

You’ll find hers cannot be the same;

‘Tis noble confidence in men,

In women, mean, mistrustful shame.

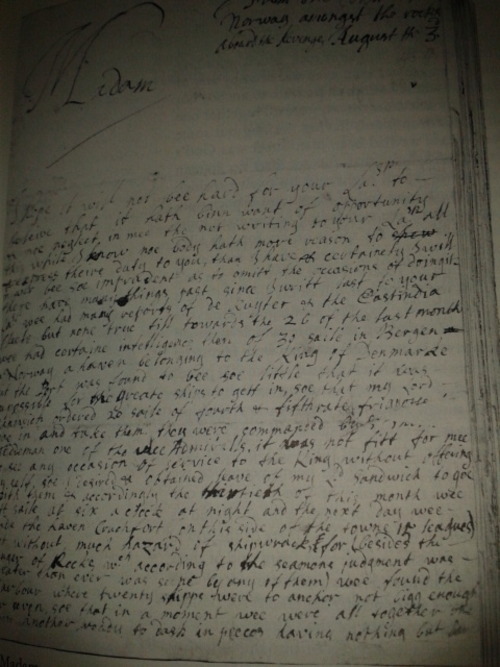

I’m not going to hide my distaste for Henry Wilmot, father of John, as I rather think he spent most of his life drunk and making poor choices that almost got a lot of people killed. For example, taking part in an active army plot against parliament in 1641 for which he was expelled from the House of Commons and committed to the tower.

Nevertheless he took over from Prince Rupert as Commander of all the Royalist Cavalry and aided Charles I in many battles. However he subsequently made contact with the Earl of Essex, the parliamentarian commander-in-chief. Charles I saw this as treason and Henry was arrested on August 8th, 1644, he was stripped of all offices and was exiled to France in return for his charges being dropped, (by doing this he escaped execution.)

Charles II did not share his father’s opinion of Henry and he brought him back from France to be a Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Charles II placed great trust in Henry, so much so that after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester, Charles allowed Henry to hide him and then help him escape to the continent.

They shared the subsequent European wanderings, with Henry visiting Emperor Frederick III, Nicolas II Duke of Lorraine and Frederick William Elector of Brandenburg on Charles’ behalf. However Wilmot refused to disguise himself and declined to travel on foot, causing more than a few problems for the exiled King Charles.

In March 1655, Wilmot was back in England and led an unsuccessful uprising on Marston Moor and upon it’s failure, Wilmot once again fled the country.

He died in 1656 as a result of sickness in an overcrowded barracks in Bruges.

I could love thee till I die,

Would'st thou love me modestly,

And ne'er press, whilst I live,

For more than willingly I would give:

Which should sufficient be to prove

I’d understand the art of love.

I hate the thing is called enjoyment:

Besides it is a dull employment,

It cuts off all that’s life and fire

From that which may be termed desire;

Just like the bee whose sting is gone

Converts the owner to a drone.

I love a youth will give me leave

His body in my arms to wreathe;

To press him gently, and to kiss;

To sigh, and look with eyes that wish

For what, if I could once obtain,

I would neglect with flat disdain.

I’d give him liberty to toy

And play with me, and count it joy.

Our freedom should be full complete,

And nothing wanting but the feat.

Let’s practice, then, and we shall prove

These are the only sweets of love.

And after singing Psalm the Twelfth

He laid the book upon the shelf

And looked much simply like himself;

With eyes turned up as white as ghost,

He cried ‘Ah, Lard! ah, Lard of Hosts!

I am a rascal and thou know'st!’“

When John was born, John Gadbury, famous astrologist and almanac maker cast his horoscope. He declared that the conjunction of Venus and Mercury gave the infant an inclination to poetry. The position of the sun “bestowed a large stock of generous and active spirits, which constantly attended this excellent native’s mind, insomuch that no subject came amiss to him.”

- From A Profane Wit: The Life of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester by James William Johnson.

I am by fate, slave to your will

And shall be most obedient still.

To show my love I will compose ye,

For your fair finger’s ring, a posy,

In which shall be expressed my duty,

And how I’ll be forever true t'ye.

With low-made legs and sugared speeches,

Yielding to your fair bum the breeches,

I’ll show myself in all I can,

Your faithful, humble servant,

John.

According to one account, Rochester wrote this verse “extempore to his Lady, who sent a servant on purpose desiring to hear from him, being very uneasy at his long silence.”

On the left is John’s half brother Charles who died between 1652 and 1657.

On the right is John’s son Charles.

The resemblance is striking, don’t you think?

Post link

Just a quick note of discussion after seeing a post on that there cully of a blog fuckyeahcharlesthesecond.

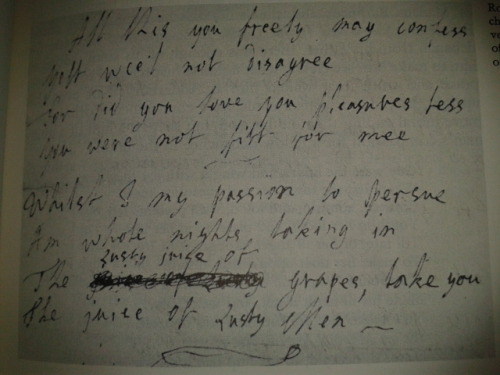

There are several different versions of most of Rochester’s poems floating around, both published physically and on the internet. The original versions were published via manuscript as opposed to print and it is well known that many were doctored posthumously either by his family or those pesky Victorians.

Generally the poems published on this blog appear as they are printed in “The Complete Poems of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, edited by David M. Vieth”

The discrepancy in language between different versions is something that is up for discussion. Standardised spelling wasn’t around until Samuel Johnson’s dictionary of 1755 and that delightful thing we call The Great Vowel Shift hadn’t quite finished wreaking havoc on the English Language.

If you have a problem with the way any of the poems on this blog are written then you can send an ask, I’m willing to discuss it rationally.

But please don’t flat out tell me I’m wrong, that’s a bit rude.

Thanks for reading,

Kit (owner, moderator, creepy Rochester fangirl.)

According to several early sources, Charles II and some of his courtiers, drinking healths, were at a loss for a rhyme for “Lisbon.” Rochester entered, raised his glass and spoke these lines.

A health to Kate!

Our sovereign’s mate,

Of the royal house of Lisbon.

But the Devil take Hyde,

And the bishop beside

Who made her bone his bone.

You can judge for yourself the success of his rhyme.

As some brave admiral, in former war,

Deprived of force, but pressed with courage still,

Two rival fleets appearing from afar,

Crawls to the top of an adjacent hill;

From whence (with thoughts full of concern) he views

The wise and daring conduct of the fight,

And each bold action to his mind renews

His present glory, and his past delight;

From his fierce eyes, flashes of rage he throws,

As from black clouds when lightning breaks away,

Transported, thinks himself amidst his foes,

And absent yet enjoys the bloody day;

So when my days of impotence approach,

And I’m by pox and wine’s unlucky chance,

Driven from the pleasing billows of debauch,

On the dull shore of lazy temperance,

My pains at last some respite shall afford,

Whilst I behold the battles you maintain,

When fleets of glasses sail about the board,

From whose broadsides volleys of wit shall rain.

Nor shall the sight of honourable scars,

Which my too-forward valour did procure,

Frighten new-listed soldiers from the wars.

Past joys have more than paid what I endure.

Should hopeful youths (worth being drunk) prove nice,

And from their fair inviters meanly shrink,

‘Twould please the ghost of my departed vice,

If at my counsel they repent and drink.

Or should some cold-complexioned set forbid,

With his dull morals, our night’s brisk alarms,

I’ll fire his blood by telling what I did,

When I was strong and able to bear arms.

I’ll tell of whores attacked, their lords at home,

Bawds’ quarters beaten up, and fortress won,

Windows demolished, watches overcome,

And handsome ills by my contrivance done.

Nor shall our love-fits, Cloris, be forgot,

When each the well-looked link-boy strove t'enjoy,

And the best kiss was the deciding lot:

Whether the boy fucked you, or I the boy.

With tales like these I will such heat inspire,

As to important mischief shall incline.

I’ll make them long some ancient church to fire,

And fear no lewdness they’re called to by wine.

Thus statesman-like, I’ll saucily impose,

And safe from danger valiantly advise,

Sheltered in impotence, urge you to blows,

And being good for nothing else, be wise.

Her father gave her dildoes six

Her mother made ‘em up a score

But she loves naught but living pricks

And swears by God she’ll frig no more.