#larry cohen

The following article appeared in the September 2013 issue of the now-defunct Shadowland Magazine.

God Told Him To!

The Cinema of Larry Cohen

By Will Sloan

Killer babies! A deadly snackfood! A winged serpent in the Empire State Building! An abducting ambulance in the streets of New York! A man trapped in a phone booth by a sniper! No doubt about it, writer/director/producer/force-of-nature Larry Cohen is one of horror cinema’s masters of the high-concept. But for a 55-year career that has been canonized by Robin Wood, trashed by Pauline Kael, feted by Lincoln Center, and has encompassed every genre from horror to blaxploitation, erotic thrillers, lowbrow comedies, westerns, a political biopic, and not one, not two, but three screenplays about telephones, this descriptor seems vaguely inadequate. So here’s a high-concept for you: Larry Cohen is one of cinema’s masters, period.

Cohen began his directorial career with Bone (1972), an acidic comedy about a black burglar in upper-class L.A. and the sexual threat he poses. Cohen likes to point out that had Kael not eviscerated it The New Yorker, he might have had an entirely different career. While we may mourn the dead-end his debut represents, we should be thankful that Bone led to the blaxploitation film Black Caesar (1973), which led to his breakthrough It’s Alive! (1974), which led to so many warped classics – Q: The Winged Serpent,God Told Me To,The Stuff,The Ambulance,Island of the Alive, and A Return to Salem’s Lot among them. Like George A. Romero, he would become a master of smuggling humor and politics into lowbrow horror fare. Like Ed Wood (and believe it or not, I mean this as a compliment), he would force the viewer to ask what, exactly, is “good” and “bad” – and whether such distinctions matter when the results are so flavorful.

Given the outrageous nature of his work – not to mention his durability in the world of exploitation filmmaking – one imagines Cohen could have thrived as a salesman, or perhaps a carnival barker. By his own account, he entered show business through sheer force of will, writing and submitting teleplays as a teenager until, he says, he was finally able to shame some people into hiring him. In the ‘60s, his career picked up: he pumped out scripts for The Fugitive,The Defenders,Branded, and other shows, and as a screenwriter, he landed a few high-profile gigs, including Return of the Magnificent Seven (1966) and Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting(1969).

It was during these years that Cohen no doubt established himself as a master of the quick, zingy premise, and working for American International Pictures to direct Black Caesar, he presumably received a crash-course in low-budget, guerilla shooting. Bone had already established his off-kilter sense of humor (best when it’s bubbling just beneath the surface), but with It’s Alive!, Cohen decisively became Larry Cohen.

In the opening scenes, we join a middle-class couple preparing to welcome its second child – which, we learn, they had briefly considered terminating. The child is born, or, more accurately, unleashed – a fanged, deformed monstrosity, barely recognizable as human. It mangles the hospital staff and flees out the skylight, leaving the parents and doctors to make sense of what they’ve seen. While the mother (Sharon Farrell) becomes distraught with grief, the father (John P. Ryan) does everything he can to distance himself from his offspring – disowning him, branding him a “monster,” and joining in the hunt to capture and kill him.

At times, It’s Alive! is a frankly goofy creature feature – the baby, with its rubbery teeth and claws, looks uncannily like a puppet designed by Rick Baker on a budget, and Bernard Hermann contributes an especially ripe score (not criticizing, just observing). But unlike most monster movies, It’s Alive! is best in its quiet moments, as the parents descend into confusion, heartbreak, and denial. In the climactic scene, when the father confronts his child and finds that he cannot kill it, Cohen doesn’t succumb to bathos, and he doesn’t tidily wrap things up. Ryan’s sensitive, vaguely pitiable performance conveys the pain of an unconditional parental love that endures even when the baby is unplanned and unwanted. With It’s Alive!, we see the full flowering of the key elements of Cohen’s work: a serious social consciousness, an affection for underdogs and outsiders, and an irreverent, unpredictable approach to genre.

***

The common rap on Cohen is that his films are clever and entertaining, despite being slapdash. Whether by temperament or economic reality, Cohen gives the impression of someone who doesn’t sweat the small stuff. His editing is sometimes haphazard (see: the early supermarket scene in The Stuff), characters sometimes drift in and out of his scripts (“By the time Sandy Dennis made her second appearance, I’d forgotten she was in the film” – Roger Ebert on God Told Me To), and his sense of mise-en-scène varies from film to film. His wild biopic The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977) was partly shot at real Washington D.C. exteriors on the fly, partly on backlots, combining for an odd aesthetic experience.

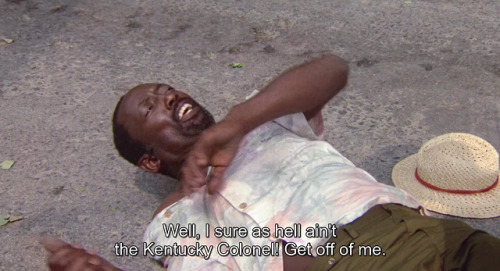

As with Roger Corman and Ed Wood, fans celebrate Cohen nearly as much for his resourcefulness and off-screen chutzpah as his work. Stories abound of Cohen and company risking arrest by filming without permits: when Fred Williamson staggers through Harlem after being stabbed at the end of Black Caesar, he’s surrounded by real New Yorkers who have no idea what’s going on; gunshots from the Empire State Building finale of Q: The Winged Serpent led to the police being called.

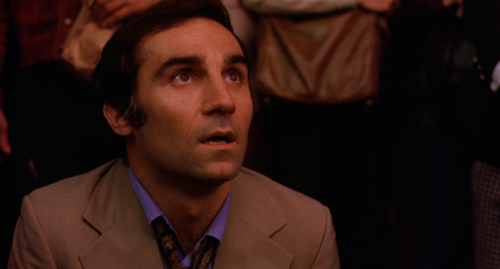

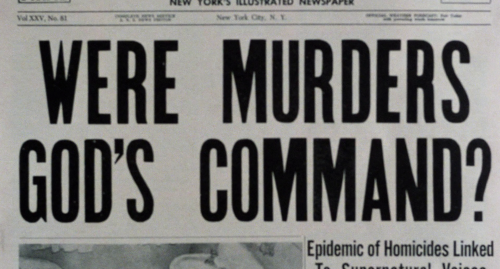

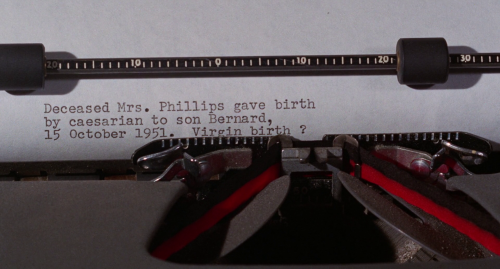

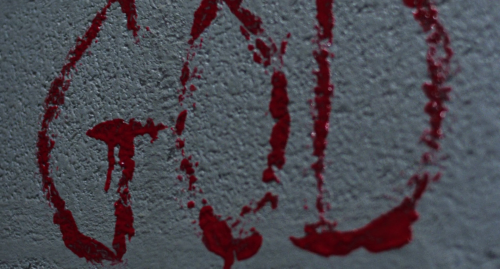

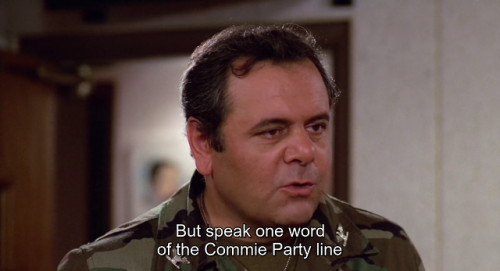

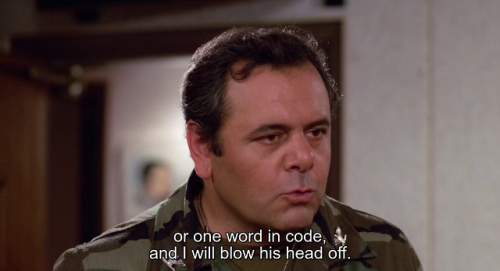

Many of Cohen’s faults, virtues, and faults/virtues are a matter of necessity. Even when he worked at major studios like Warner Brothers and MGM, Cohen never worked with comfortable budgets. But if you’re one of the cultists who seek out his work, his freewheeling approach to film grammar is exactly what you respond to. Putting everything else aside, Cohen’s guerilla shooting style has established him as one of the best chroniclers of New York City in film history. The city breathes in God Told Me To (1976), his grimy thriller about a mysterious force that sends ordinary people on killing sprees because “God told me to.” Cohen invaded the St. Patrick’s Day Parade for an extraordinary scene in which a possessed NYPD officer (Andy Kaufman, of all people) begins opening fire on the crowd. No, Cohen and Kaufman did not have permission to be there – cutting between real scenes of the parade and shots of Kaufman firing away, the scene proves that despite his slapdash reputation, Cohen is capable of rather virtuoso feats of editing.

New York is even more pungent in Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), which comes close to encapsulating everything wonderful about Cohen’s cinema. In Q, there are about three competing plot strands, none of which seem to belong together: a splattery monster movie about a prehistoric Quetzalcoatl, rendered in sub-Harryhausen claymation, that nests in the needle of the Empire State Building and feeds on roof-dwellers; a straight-faced police procedural starring David Carradine and Richard Roundtree; and an offbeat comedy starring Michael Moriarty as lowlife who discovers the nest and demands $1 million for the information.

Q was reportedly conceived in all of one week, after Cohen was fired from I, the Jury (1982). He immediately went to work on another script, using his buyout money to pay for preproduction and drawing on industry connections to get quick financing. By chance, he met Michael Moriarty (then fresh off his triumph in the miniseries Holocaust) at a restaurant, and sold him on the lead role, and called on his old army buddy David Carradine to round out the cast. The memorable scene where Carradine and Moriarty meet for the first time at a piano bar was shot without Carradine knowing what character he was playing, or even what the film was even about.

InQ, Jimmy Quinn (Moriarty) is a petty larcenist, fresh out of prison and already in trouble with the mob. Moriarty plays him to the hilt – he’s jittering, hyperventilating, and unreasonably self-satisfied. When Quinn leads the police force up the Empire State Building, he has the skip in his step and smile on his face of someone who has never felt such power. Moriarty plays Quinn as someone who doesn’t deserve to be the main character of a movie, and knows it, and relishes it. When he gets hit by a car and develops a limp, Moriarty turns it into just another bullshit affectation by a terminal bullshitter.

What I value most about Cohen – which goes hand-in-hand with his alleged sloppiness – is this sense of whimsy. Where many of his B-movie progenitors shot similar stories in a listless, indifferent style (think of the lesser works of Roger Corman or Bert I. Gordon, with their gray protagonists in their gray offices talking endlessly about the off-screen monsters), you can count on Cohen to throw in enough eccentric elements to keep you off balance. “Sometimes the scenes that really make a movie are the little scenes that have nothing to do with advancing the action, but just add a little something,” Cohen told Andrea Juno and Vale in the book Incredibly Strange Films.

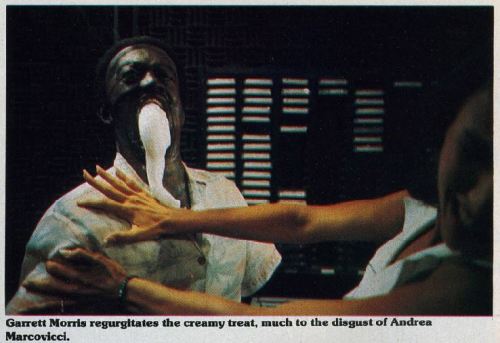

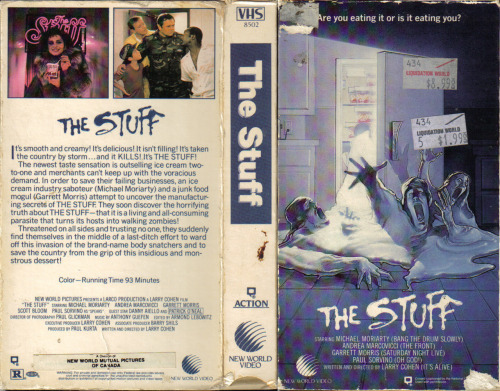

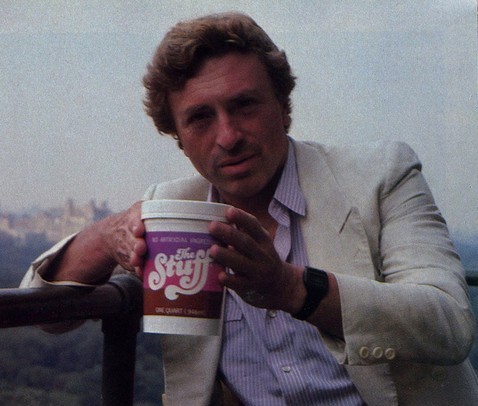

InThe Stuff (1985), his weirdest film, the discovery of a mysterious creamy substance leads to an all-consuming snackfood sensation, complete with obnoxiously omnipresent marketing campaign. Rather than the usual square-jawed hero, Cohen again gives us Michael Moriarty, giving a wry performance as an ex-FBI agent hired by the dairy industry to investigate and destroy the Stuff. Sprinkled throughout are shots at America’s insatiable appetite for flashy advertising and sugary garbage, and our reluctance to question what we’re eating so long as everyone else is consuming it too. “Are you eating it, or is it eating you?” says Moriarty, who might as well be referring to McDonald’s.

The unheralded gem of the Cohen oeuvre is Special Effects (1984), his contribution to the erotic thriller genre. Eric Bogosian stars as a down-on-his-luck film director who kills an aspiring actress (Zoë Lund) during a one-night stand. Having covertly filmed the murder, he uses the footage as the bedrock for his comeback picture, an ultra-realistic mystery made in collaboration with the unknowing actress’ husband and the detective on the case. Key to Cohen’s black-comic approach to this sordid material is an amusing performance by Bogosian, in his first leading role, who conveys what would happen if a Hitchcock movie had actually starred Hitchcock (or at least the detached, witty, all-knowing sociopath he played on his Alfred Hitchcock Presents series). “Who’s your favorite filmmaker?” someone asks Bogosian. “Abraham Zapruder,” he replies.

***

Since the watchable but anonymous blaxploitation revival Original Gangstas (1996), Cohen has been absent from feature film directing. For the past two decades, he has pumped out screenplays and treatments for projects both prestigious (Sidney Lumet’s Guilty as Sin, Joel Schumacher’s Phone Booth, Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers) and not (Maniac Cop 3,Uncle Sam, and – always with the high-concepts – the artificial insemination thriller Misbegotten). His most recent script to see wide release was the regrettable Captivity (2007), an odious attempt to ride the Saw/Hostel wave, laced with some half-baked commentary on gender relations.

But there are signs of life in the old Larry Cohen. In 2006, he reemerged to direct Pick Me Up, a lightly enjoyable hourlong episode of the anthology series Masters of Horror. Working for the first time from someone else’s script, Pick Me Up is Cohen’s slickest production (perhaps benefitting from a seasoned television crew), but still unmistakably his, thanks to the welcome return of Michael Moriarty. As an avuncular trucker who’s also a serial killer, his odd, charismatic performance brings back fond memories of Q.

And, with a little luck, we may soon welcome the master’s first theatrical feature in 17 years. Earlier this year, Cohen told Film Comment that he is at work on Delusion, a new thriller to be shot in Chicago. Cohen has not revealed the scale of the story, nor where he hopes to find funding, but one wonders if the digitally-abetted boom in microbudget filmmaking might be conducive to Cohen’s cinema. With so many Sharktopuses on our Netflix queues, we could certainly use Larry Cohen. In a roomful of David Carradines, his films are Jimmy Quinn.

***

WILL SLOAN: I was happy to hear that you’re planning a new movie.

LARRY COHEN: Always planning a new movie. It’s a thriller – Delusion, it’s called. I usually don’t tell the plots of my movies in advance, because then I end up seeing them on television or something.

WS: Is it Hitchcockian?

LC: Yeah, of course. Isn’t it always?

WS:WasAlfred Hitchcock Presents one of the shows you sent spec scripts to at the start of your career?

LC: I never sold anything to him. I tried to get a job on that show, but I never did. I guess he’s a major influence, ever since I was a kid growing up on those kinds of pictures, watching them over and over again. And I got to meet Hitchcock a few times, and I got to have Bernard Herrmann, his composer, do a picture for me. And another composer, Miklós Rózsa, who did Spellbound, he did a picture for me also. So I’m kind of mixed up with him.

WS: In your early years, you wrote for television pretty much nonstop. How much did that impact your way of working?

LC: I just latched onto people and did free work for them until they got so tired of seeing me around that they finally hired me. I just always felt that the best friend you’ve got is yourself and you can’t expect other people to do things for you.

I liked writing, I enjoyed seeing the finished product whether they bought it or not, and that still holds true today. The biggest kick I get is the writing of the script, and then when the finished product is done, whether it gets made or not, I’m glad I wrote it. I have loads of scripts around that have never been produced – I’ve got ten of them on my website, LarryCohenFilmmaker.com, that I’m very happy I wrote and are available for people to read and imagine the movie for themselves.

WS: Do you have a writing routine?

LC: I never had a routine, but I always found plenty of time to write. I never said I had to write until 8 o’clock in the morning until noon or anything like that. In my early days, when I was married and had kids, I used to write very late at night after everybody else went to sleep, because I didn’t want to be one of those fathers who was always chasing the kids away because he was busy working.

WS: I know you have a reputation as being “Mr. High-Concept.” Do you think of yourself that way? Do you always start with a high-concept?

LC: I start with an idea that I think is worth writing. To me it’s a high-concept, or I probably wouldn’t have put the time in. A lot of my work is what they call “spec work,” where nobody hires me to do it, I just write the script because I want to. Usually I start it and I want to see how it’s going to turn out, so I finish it. I often don’t have a finish for the thing when I start it, I just want to see where it’s going to go. It’s not like I’m filling out squares that have already been drawn in advance – I’m making it up as it’s happening. That’s the way I like to work the best.

WS: Do you think of yourself more as a writer who directs?

LC: Yes, absolutely. The writing comes first. The writing is the essence of the motion picture. If you don’t have it at the beginning, you’re not going to have it at the end – you can’t pull things out of the air that don’t exist. When I’m writing the script, I can improvise all I want to. When I get the picture on the floor with the actors, it depends on who the actors are and what the actors contribute to the story.

I often make up elements to suit the actors. Like in Q, the character that Michael Moriarty played had nothing to do with playing the piano in nightclubs, he was just a straight character until Michael came aboard. I heard Michael listening to recordings of his own piano playing, and I said, ‘Hey, listen, let’s take that and put it in the movie.’ I told my assistant, ‘Go find me a club that open during the day that has a piano and a bar, and we’ll make up a scene. We’ll shoot tomorrow.’ On a regular studio picture, you couldn’t do something like that – everybody would go nuts saying, ‘That’s not in the script, that’s not in the schedule, it’s gonna delay production.’ On my pictures, if I want to do something like that I can do it, so we created the whole subplot of him being a failed piano player who ends up participating in the robbery because he can’t get a job. It added dimension, and it allowed Michael to write a song for the movie, and he enjoyed the whole process. As soon as the actors start having a good time, we all have a good time.

WS: That’s always the first scene anyone mentions when they talk about Q, even though it has nothing to do with the winged serpent.

LC: Absolutely. If you’re making a picture on a normal studio basis, they’d say, ‘That has nothing to do with the monster, so what are you putting that in for? You’re going to add to the budget of the picture and delay the production.’ By the time you’ve made explanations to people, it would be too late to do it anyway. The fact that I make pictures that are low budget usually means I can go off and do them on my own and I don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to do anything. I can just make up whatever movie I want to make up.

WS: Writer-directors often say they starting directing to preserve the integrity of their scripts. Was that the case with you?

LC: Well, I had a lot of pictures that I wrote that I didn’t like. I thought they had good scripts, and the pictures didn’t add up to the quality of the script. I decided, ‘Maybe I should direct a picture and see how it works out,’ and my ex-wife bought me a director’s viewfinder as a gift and said, ‘Go ahead, do what you want to do.’ I ended up directing, but I suppose if all the pictures I had written had turned out to be great, I might never have directed. As it was, I’m partial to the ones I directed.

WS: You started with Bone, but It’s Alive was the one that set you on a path more towards horror/exploitation films. Did you anticipate this?

LC: Oh, you never know. If Bone had received more acclaim when it came out, I might have had a different career. Bonewas really in the same category as something like the movies Mike Nichols was making back in those days, like Carnal Knowledge. If the picture had received the kind of notices that I’d hoped for, I probably would have gotten a different career, but it wouldn’t have been the same career, because if I’d gotten into making studio pictures, I never would have had the autonomy that I had on my low-budget pictures.

In the end, I’m happy that I followed the route that I did, because I got to make pictures without interference. I don’t do too well with having to deal with people butting into my work schedule and my plans. I’m not a team player. They say that movies are a collaborative effort, but most of the time in my movies, I’m the whole cheese. I write, produce, edit the pictures, and usually come up with the ad campaigns.

WS: You’ve worked at major studios – have you found it hard to work in that system?

LC: Well, major studios always have a staff of producers and executives that have to justify being there. They have to put their two cents in – after all, they’re getting a salary every week, and their job is to interfere. If they don’t interfere, I guess they don’t think they’re earning their keep. Basically, they’re bird-dogging you, they’re looking at your dailies, they’re looking at the production schedule, they usually put a production manager on the picture who isn’t working for you, he’s working for the studio. He’s kind of the spy on the set – you’re looking over your shoulder at someone who’s watching you and doesn’t have your interests at heart. Usually on my pictures, I don’t have anybody like that. The director’s guild makes me put a production manager on the picture, but very often I’ve just paid the production managers their salary and told them not to come to the set, just go get another job. They never know what I’m doing – I’m the only one who knows what I’m doing.

WS: I just watched It’s Alive again and was surprised by how sad it was.

LC: Yeah, well, it is a tragic movie. It’s not so much a horror movie as a movie about the disintegration of the American family. Some people are Warner Brothers said they found it extremely depressing, but they went in expecting to see a pure horror picture, and the film had a lot of characterization and very, very good acting.

WS: It feels like a very relevant film.

LC: It was. I mean, people in that period of American life were estranged from their children. Kids were 15 or 16-years-old and they were smoking dope and using language and engaging in sex, and parents felt like they had a stranger living in the room down the hall. They didn’t know who that person was – defiant, angry, hostile. In some cases, fathers actually killed their kids, and when I read about that in the paper, I said, ‘Oh my god, what if you had a monster living in your house? Suppose it was born a monster, then what would you do?’ After that I sat down and wrote it.

WS: You went in a more comic direction in the sequels.

LC: Well, the second one was serious, but then when I did the third one, which was some time after that, I had Moriarty again and I thought, well, I’m not going to do the same movie I did twice before. I’m going to for a different approach, with more of a manic humor to it.

WS: You and Michael Moriarty are sort-of the Dietrich and Von Sternberg of a certain kind of film. What was your working relationship with him?

LC: We had fun together. We improvised stuff. The first picture we did was Q, and the first day we shot, I heard his music on a tape and changed the script around. After that I more or less owned him. When you sit down and write a scene for an actor and they see you write it, they learn it right away and they play it. After that, you’re kind of a magician and you can more or less get the actor to do anything. With Moriarty, he had a marvelous concentration – he could be playing a scene and I could be off-camera yelling out lines of dialogue to him, and without a flinch he would just put that into the scene. He’d never worked with anybody like that before.

Once you get something going like that with an actor, it energizes them, and they’re having a great time. One of the comments I’ve got from critics over the years is that the cast looks like they’re having a great time. And it’s true, they are – I’m entertaining them. Unlike studio pictures, I’m the star of the movie, it all revolves around me, and everybody wants to see what I’m going to do next, including me.

WS: There’s something unstable about your movies, like the odd mix of comedy and horror in something like The Stuff. Is that a hard tone to cultivate?

LC: It’s my way. The Stuff had more humor in it than most of my other pictures beforehand. As a matter of fact, the studio that made the picture was disappointed in the film; they thought it should be more horrific and less satiric. But, that’s what I made, and that’s what they had to release. Now, over the years, it’s gained a lot of favor because of the humor, because of the characters like the Paul Sorvino character and the one that Moriarty played, but originally the studio was looking for a real horror movie like The Blob or something. They didn’t get it.

The reviews were phenomenal, but the studio just didn’t support the picture with the review ads that we needed. If you get good reviews, it can be very dangerous, because in order to exploit the reviews, the studio has to buy big ads and put quotes in, and that means a lot of space in the newspaper, and that means a big expense. If they don’t want to go to that expense, all those reviews are gone the next day, they’re only in the newspaper for one day. In their case, they just didn’t want to spend the money for the advertising.

WS: How about Q? That’s another one that feels like several different movies running parallel. Sam Arkoff produced it – how did he feel about the movie?

LC: Sam didn’t have much to say about it, he just gave me some money and left me alone. I’d given him a couple of hits before – Black Caesar,Hell Up in Harlem – so he didn’t get in the way of anything. He just wanted to know if there were going to be enough special effects shots of the monster, because he was looking to sell the picture in Europe, and he knew it would sell if there was a monster flying around. But he never interfered. That picture did very well, box office-wise and critically too – at least the distributors were willing to take full-page ads, and they did some nice poster work.

WS: I loved the article you wrote in Film Comment about your ill-fated experience with Bette Davis on Wicked Stepmother[“I Killed Bette Davis,” July 2012].

LC: Well, that was all true. I really enjoyed the time I spent with her – she was a great old dame, and I loved hearing all the anecdotes about the old days of Warner Brothers and the inside gossip. I had fun with her, particularly during the preproduction period.

Once we got into the actual shooting of the film, she was extremely nice to me, but something was bothering her. I didn’t know at the time it was her dentures, and they had cracked before the picture had started and she was trying to get through the scenes without having her teeth dislodge. She kept stopping all the time to push her teeth back into place with her tongue, so she gave me some very odd line readings and some pacing that was inexplicable. I said to myself, ‘What’s the story with Bette Davis? She’s the last one I would expect to be doing the lines like this,’ but she was just having trouble. When she saw herself in the dailies and realized how it was, she decided she had to get out of there.

WS: She had a very unusual presence in the movie, almost otherworldly.

LC: She was so skinny, so withered. People didn’t want to see Bette Davis like that. When I first met her and my agent was with me, after we left her house my agent said, ‘You can’t possibly make a movie with her.’ I said, ‘Yeah, she doesn’t look good, but when she starts talking, it’s Bette Davis.’ But of course, I didn’t know her dental problems would make even the talking extremely difficult to handle. She was better off leaving when she did [after one week of filming]. As a matter of fact, MGM insisted that I cut out some of her footage, so there was even less of her in the movie than we actually shot.

But I did like the fact that Lionel Sander was so good in his part, and Barbara Carrera was so good in her part, and so many of the people did nice jobs. I thought it was a very cute movie. It suffered from the Bette Davis debacle, but if you saw the picture with an audience, there were plenty of laughs.

WS: Of the movies you’ve written for other directors, do any stand out for you?

LC:Phone Booth was good. I thought Joel Schumacher did a good job with that. Maybe it could have been better, but as opposed to others that were really bad, this was a pretty good movie.

WS: What did you think of Captivity?

LC: Terrible. Absolutely disastrous. They rewrote the script and took all the humor out of it. You’d never know it was one of my pictures, they just deleted anything in the first third of the script that was humorous that made you like the characters and made you get involved. Then, poor Roland Joffé, they took the picture away from him and went back and shot horror scenes that he hadn’t directed – stuff that was really vile and disgusting. All in all, it was a piece of junk.

WS: I was surprised to learn that Special Effects was a script you wrote before most of your other movies. Since it’s about an established director whose career is in a downturn, it feels like the work of someone who has been around the block.

LC: That was one of the first scripts I ever wrote with the intention of directing, and we never put it together. Years later, I got the opportunity to make a couple of low-budget films for a company called Hemdale, and I gave them the script and said, ‘Can I do it?’ We changed it around a bit, rewrote it, and made the picture.

I particularly like that film. I think it has a lot to say about the movie business and about creativity, and it was beautifully shot. I kinda like that movie.

WS: How do you feel about the director character that Eric Bogosian played? Do you sympathize with him?

LC: Well, it wasn’t me, it was more like Peter Bogdanovich and Michael Cimino who had big successes and then all of a sudden the whole bottom fell out on their careers and they couldn’t get a job anymore. They were very demanding and difficult when they were on top, and people didn’t like them, but they were successful and people put up with them. When they slipped, nobody wanted to put a hand out to help them get back up again. So, there was a whole raft of directors like that that you see all over the place – they all disappeared from the horizons and I don’t know what became of them.

I look at their careers and mine and I go, ‘Well, I never got up there to the top, but I never had a huge collapse like they had.’ It must be tough to be at the very pinnacle of the business, get Oscar nominations and critical acclaim, and all of a sudden, nothing. My career is more or less on even keel – I’ve made the pictures I wanted to make, they’ve had a moderate success but I’ve made a lot of money off them, and I just keep working. Thank God I never had that meteoric rise or meteoric fall.

Ten years ago Emmet had the opportunity to interview Larry Cohen, to promote a visit to Australia as part of MonsterFest October 2012. This episode features segments of their conversation, released as a tribute to mark the 4 year* anniversary of Cohen’s passing.

During their conversation, Cohen raises his feelings about the use of CGI effects in horror cinema, how his themes have allowed a new generation of film-fans to rediscover his films, as well as shout outs to Bruce Campbell, Quentin Tarantino, and The Big Lebowski.

Also for no apparent reason Emmet decides to shit on Sydney as a filming location!?