#latin american literature

Gabriel García Márquez, Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

translated Edith Grossman (1988)

Fermina Daza was horrified when she heard the boat’s horn with her good ear, but by the second day of anisette she could hear better with both of them. She discovered that roses were more fragrant than before, that the birds sang at dawn much better than before, and that God had created a manatee and placed it on the bank at Tamalameque just so it could awaken her. The Captain heard it, had the boat change course, and at last they saw the enormous matron nursing the baby that she held in her arms. Neither Florentino nor Fermina was aware of how well they understood each other: she helped him to take his enemas, she got up before he did to brush the false teeth he kept in a glass while he slept, and she solved the problem of her misplaced spectacles, for she could use his for reading and mending. When she awoke one morning, she saw him sewing a button on his shirt in the darkness, and she hurried to do it for him before he could say the ritual phrase about needing two wives. On the other hand, the only thing she needed from him was that he cup a pain in her back.

Florentino Ariza, for his part, began to revive old memories with a violin borrowed from the orchestra, and in half a day he could play the waltz of “The Crowned Goddess” for her, and he played it for hours until they forced him to stop. One night, for the first time in her life, Fermina Daza suddenly awoke choking on tears of sorrow, not of rage, at the memory of the old couple in the boat beaten to death by the boatman. On the other hand, the incessant rain did not affect her, and she thought too late that perhaps Paris was not as gloomy as it had seemed, that Santa Fe did not have so many funerals passing along the streets. The dream of other voyages with Florentino Ariza appeared on the horizon: mad voyages, free of trunks, free of social commitments: voyages of love.

…Contrary to what the Captain and Zenaida supposed, they no longer felt like newlyweds, and even less like belated lovers. It was as if they had leapt over the arduous calvary of conjugal life and gone straight to the heart of love. They were together in silence like an old married couple wary of life, beyond the pitfalls of passion, beyond the brutal mockery of hope and the phantoms of disillusion: beyond love. For they had lived together long enough to know that love was always love, anytime and anyplace, but it was more solid the closer it came to death.

…The Captain looked at Fermina Daza and saw on her eyelashes the first glimmer of wintry frost. Then he looked at Florentino Ariza, his invincible power, his intrepid love, and he was overwhelmed by the belated suspicion that it is life, more than death, that has no limits.

Post link

Deep green and silent…

Literature isn’t innocent. I’ve known that since i was fifteen. And i remember thinking that then, but I can’t remember whether I said it or not, and if I did, what the context was. And then the walk (but here I have to clarify that it wasn’t five of us anymore but three, the Mexican, the Chilean, and me, the other two Mexicans having vanished at the gates of purgatory) turned into a kind of stroll on the fringes of hell.

The three of us were quiet, as if we’d been struck dumb, but our bodies moved to a beat, as if something was propelling us through that strange land and making us dance, a silent, syncopated kind of walking, if I can call it that, and then I had a vision, not the first that day, as it happened, or the last: the park we were walking through opened up into a kind of lake and the lake opened up into a kind of waterfall and the waterfall became a river that flowed through a kind of cemetery, and al of it, lake, waterfall, river, cemetery, was deep green and silent. And then I thought it’s one of two things: either I’m going crazy, which is unlikely since I’ve always had my head on straight, or these guys have doped me. And then I said stop, stop for a minute, I feel sick, I have to rest, and they said something but I couldn’t hear them, I could only see them coming closer, and I realized, I became conscious, that I was looking all around trying to find someone, some witness, but there was no one, we were in the middle of a forest, and I remember I said what forest is this, and they said it’s Chapultepec and then they led me to a bench and we sat there for a while, and one of them asked me what hurt (and the word hurt, so right, so fitting) and I should have told them that the problem was probably that I wasn’t used to the altitude yet, that it was the altitude that was getting to me and making me see things.

~The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolano, page 154-155

“…a kind of stroll on the fringes of hell.”

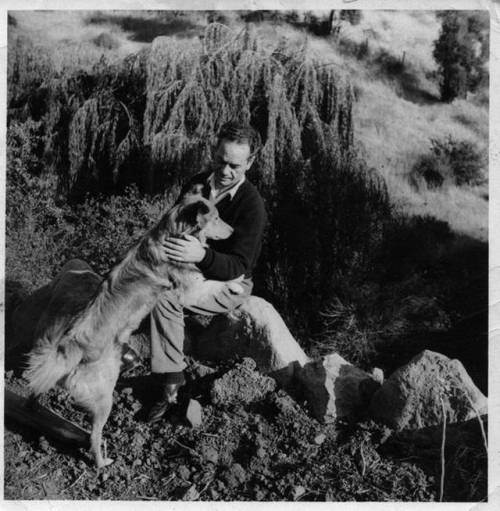

(“Untitled” [2002] by Just Loomis)

To celebrate the relaunch of its website, The New Yorker is opening up its archives for free this summer. Take a half hour and read this beautiful Bolaño story, “Clara,” from an August 2008 issue.

One night I dreamed of an angel: I walked into a huge, empty bar and saw him sitting in a corner with his elbows on the table and a cup of milky coffee in front of him. She’s the love of your life, he said, looking up at me, and the force of his gaze, the fire in his eyes, threw me right across the room. I started shouting, Waiter, waiter, then opened my eyes and escaped from that miserable dream. Other nights I didn’t dream of anyone, but I woke up in tears. Meanwhile, Clara and I were writing to each other. Her letters were brief. Hi, how are you, it’s raining, I love you, bye. At first, those letters scared me. It’s all over, I thought. Nevertheless, after inspecting them more carefully, I reached the conclusion that her epistolary concision was motivated by a desire to avoid grammatical errors. Clara was proud. She couldn’t write well, and she didn’t want to let it show, even if it meant hurting me by seeming cold.

There’s plenty more where this came from. Check it out.

-Hal-