#lee morgan

Legends section…

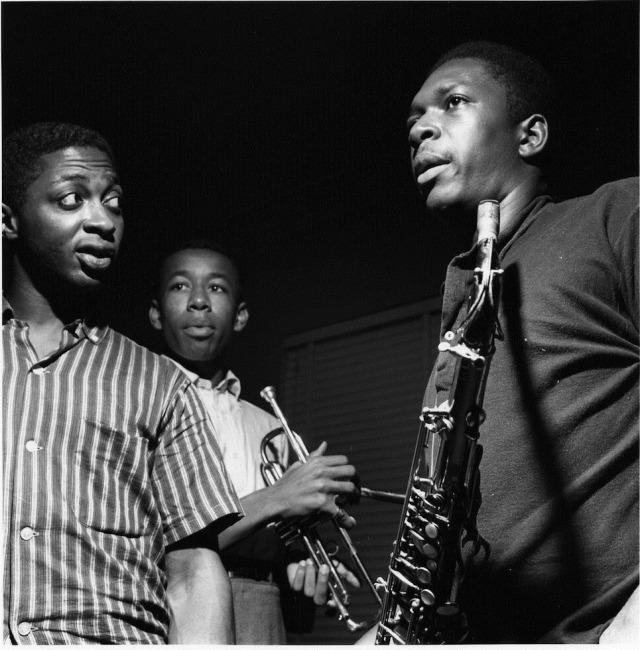

Curtis Fuller, Lee Morgan & John Coltrane

Lee Morgan in the Blue Note Records stockroom at 47 West 63rd Street, NYC (1957).

If the numbers marked on the boxes are accurate, the records are fresh from the Plastylite pressing plant and waiting to be married with jackets.

Art Blakey (The Jazz Messengers, Thelonious Monk, McCoy Tyner)

Bassist: Percy Heath. Drums: Art Blakey. Trumpet: Lee Morgan.

one more time, w/feeling:

bassist - jymie merritt

drums - art blakey

trumpet - lee morgan

Post link

Lee Morgan at a rehearsal for Reuben Wilson’s “Love Bug” session, New York City, March 1969 (Photo by Francis Wolff)

Lee Morgan, by Francis Wolff

‘The Faerie as Witch’s Familiar’

“The Witch, like the faerie, was a feared bringer of contamination, and a divine healer bringing salve from a land flowing with milk and honey. It is this very ambiguity that originally made faeries and Witches both so unpredictable and fearful to the average hedge-bound mind. The process of remov- ing this ambiguity, infantizing faeries and making Witches into kind herb wives, has been the process of defanging and declawing the Otherness, a breaking up of a whole. It does nothing to readdress the imbalance created when Witchcraft was made the black repository of all undesirable faerie characteristics, but instead damages both sides of the divide it creates. Of course it is not actually possibleto declaw the Otherworld, we only ever neuter our own awareness of it.

In Italy the mistress of the magic witch mountain, flowing with milk and honey, was called “wise Sibillia.” It was said the ancient sibyl of mount Cumae had taken refuge in a cave at the crest of the Appenines. In Reductorium Morale (c. 1360) Pietro Bersuire wrote about her Underworld paradise entered through a grotto in the mountains of Norcia, a region famed for its Witches. Nearby was a magical lake fed by water from a cavern. Whoever stayed longer than a year could no longer leave, but remained deathless and ageless, feasting in abundance, revelry, and voluptuous delights.

Sibillia was regarded as Goddess of the Witches. In Ferrara people said “wise Sibillia” led the cavalcade of Witches in their flight. At the end of their feasts, she would touch all the bottles and baskets with her wand, and they would quickly refill with wine and bread. They would then gather the animal bones into their skins, and at the faerie wand’s touch, the animals recovered their flesh and returned to life.

This archaic-sounding tradition of a faerie woman inside a mountain hitting dead animal bones and reanimating them is suggestive of the themes of initiation. Just as the faerie Witch’s bones are taken or counted and put back in, and the Witch is resurrected from a death-like sleep where they have journeyed beyond the grave, so the animal’s bones recover from death due to faerie magic.

But true to the archaic ambivalence we’ve discussed above, Sibylla is not only associated with golden wands and beautiful paradises, but with a half-serpent body and ordeals that involve being covered in snakes and even having to have sexual intercourse with them. No matter what country the narratives of faerie come from there is never any making it to the land of milk and honey without a harrowing of hellish proportions first, but in some areas the faerie creatures contain more obviously archaic mixed natures. Sibillia is one of these beings. We will encounter Sibillian traditions of the Craft later in this book, as she appears both in the English Robin Goodfellow faerie traditions as Sib, and as the faerie Sibylla in Reginald Scot’s grimoire of faerie magic. From the Sibillian mountain and the Witchcraft associated with it we can see that in Italy Witches and faeries were very closely connected, just as they were elsewhere. The fairy mountain was the place you went to learn your magical arts.

One of the most striking ritual connections between the faerie seer and the Witch in Britain, as opposed to the continental examples, is the “all that lies between these two hands practice,” which we find originally in faerie material and later as a British Witchcraft initiation posed in the trial records. As early as Robert Kirk we hear of the faerie seer putting one foot under the foot of the one to be admitted to the secrets of faerie seership and the other on the head whilst looking over the wizard’s right shoulder, thus sponsoring them with their own power.]

We see a similar ritual repeated in trial records of the Wincanton Coven who supposedly adopted a kneeling version of this posture at their initiations. The woodcut of a Witch in this position is drawn from Joseph Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus. But the traditions of Witchcraft and faerie were often quite chronologically parallel rather than one developing off another, as Kirk admits to the fact that the posture has an “ill appearance” which implies the surrender of what is between the hands, suggesting that he already knows that such postures might be used in relation to the Devil. We have already said that Robin Artisson, whom Alice Kyteler was devoted to, was a demon by the estimations of the times but most likely also a kind of faerie. In many cases the true “religion” of Witches, if they could be said to have religious feelings that come through to us from the records, is toward their familiar spirit, who was sometimes but not always associated with the Devil when they were probably often a devil.

The Witch’s faerie familiars present us with a scene of great variety. The faerie Witch Bessie Dunlop seems to have maintained a business-like platonic relationship with her faerie familiar Tom. John Walsh of Dorset mentions working with faeries as though going out to the faerie mounds were a natural part of Witchcraft, but he never mentions a deep bond with any of them. But there are many other than Alice and her Robin who do, such as Isobel Gowdie’s sexual passion with her “devil” and Andro Man’s ongoing relationship with his Faerie Queen and almost worship for Christsonday who sounds angel-like. Ann Jeffries not only experienced romantic love with her faerie man but was bravely defended by him when she was threatened and Thomas the Rhymer was treated with affection by his Faerie Queen at the very least. Alison Person, also a faerie Witch, had an almost religious devotion to a deceased cunning man who now lived among the faeries, one William Simpson, who she said protected her from the worst intensities of the coming and going of her faerie visions by warning her when they were afoot. And Isobel Haldane, a Scottish Witch, acquired her powers after she was saved from an unwanted faerie abduction by “he that protected me from the faerie folk,”’ who was himself a faerie.

In this way a traditional abduction and blighting narrative was transformed through the agency of “he who protected me” into an initiatory ordeal from which the person emerged a Witch of power. Her devotion to “he who protected me” was no doubt almost religious in its intensity. Yet despite the obvious correlation between Witches and faerie familiars those intent on painting Witches as pure evil were loath to associate them with faerie seers. Even King James with his almost pathological fear of Witches claimed in his Demonologie that “those people whom spirits (faeries) have carried away and informed they were thought by the common folk to be the soniest [wisest] and best of life.”

Emma Wilby has taken note of this religiosity that Witches often felt towards their faerie familiars:

“[The witch] Alice Nokes (1579) claimed, when reprimanded before a church congregation, that ‘she cared for none of them all as long as Tom (her familiar) held by her side.’; … an unnamed Cambridgeshire witch (1653), being 'on the point of execution. declined to renounce the faithful friend of threescore years (that is, her demon familiar) and ‘died in her obstinacy.’

If there could be said to be an observable religious impulse behind historical Witchcraft it is not the Pagan fertility religion of early Wiccan and Neo-pagan projections, it is the animistic faith shared with faeries, and sometimes the worship of particular powerful faeries. It is a religious faith both infaeries and the knowledge, shared with faeries and perhaps given by them, that the stars and all things in life have spirits in them from the largest to the smallest and many microcosms are in each with everything moving forever in cycles. The Faith that there is an inalienable sanctity in the relationships between those that mutually nourish each other, including the relationship between a Witch and familiar spirit.

Other examples of the theme of mutual nourishment can be found in relation to the powerful hobman and witch-devil, Robin. We have already mentioned a "Robin” familiar in relation to Alice Kyteler and her Robin Artisson but this name for the witch-devil reoccurs elsewhere, including in the Robin Goodfellow story and in Somerset during the trial of the Wincanton Coven.

The “Robin” of the Wincanton Coven appeared to the principle Witch ten years before the trial as a handsome man, and later as a black dog. He promised her money and pleasure in this life if she would provide him with some of her blood that he might suck it, thus giving her soul (as in virtue rather than spirit) to him and observe his laws. This she did, pricking the fourth finger of her right hand between the middle and upper joints. He gave her a magical sixpence in return and vanished.

Although the Wincanton trial involves plenty of maleficium and they don’t directly make references to faeries, interpreting their “Robin” as a faerie man, much like Robin Artisson, has other support within the evidence. The Wincanton Coven were those who claimed their initiation involved placing everything between their two hands and thus mimicking the logic, if not the exact posture, of the faerie seer posi tion. After her pact with this mysterious man Elizabeth Styles was fed “bread and wine,” much like the sacrament Thomas the Rhymer engages in.

This simple act might seem common enough but this repast that we’ve previously called the host also carries echoes of the “faerie food.” The provision of food by faeries is given as a sign of great love from a faerie man to a woman he has impregnated. One very potent story to this effect is that of the birth of Robin Goodfellow, fathered by the Faerie King Oberon (or Obreon in older sources) upon a mortal woman. As a sign of his love for the human mother of his child he continuously feeds her. Mutton, lamb, pheasant, woodcock, partridge, quail, a never- ending supply of food is laid before Robin Goodfellow’s mother by her faerie lover. He also provided her with fine wines of many types.

The Wincanton Coven received very similar faerie food from their Robin, including a wide variety of meats and fine wine they discuss frequently, presumably because such high quality victuals would usually have been far out of their price range. At their Sabbats the Coven’s “devil” Robin, “the man in black,” would “play on a pipe or cittern” and they danced. This image of Witches dancing with a man called Robin whilst music plays is very evocative of the famous image of Robin Goodfellow, a book poster from the 1600s called “Robin Goodfellow and his mad japes” and further suggests we consider these “Robins” to be the same powerful faerie patron.

This pattern of a faerie man piping for dancing Witches is also seen quite vividly in James Hogg’s poem The Witch of Fife, where Hogg writes this particularly evocative piece of poetry about the experience of a Witch (1835) which I have transcribed outof Scots English and into standard English for ease of reading.

“And then we came to Lommond Height

So lightly we touched down;

And we drank from the horns that never grew,

The beer that was never brewed.

Then up there rose a wee, wee man

From beneath the moss-grey stone;

His face was wan like cauliflower

For he had neither blood nor bone.

He set a reed-pipe up to his mouth

And played it bonnily

Till the grey curlew and the black cock flew

To listen to his melody.”

He then speaks of how all the animals answered the faerie man’s piping and faerie, Witch and animal dance until dawn. Later in the story (which she is relating to her husband) they fly on their hemlock as far as Lapland, were they find the local faeries all in array, for the “geni of the north” were keeping their holiday. Hogg then writes:

“The warlock men and the weird women

And the fays of the wood and steep,

And the phantom hunters all were there,

And the mermaids of the deep.”

Here we see faeries, Witches /Warlocks, the phan tom hunters of the Wild Hunt and mermaids linked together in a Sabbat narrative, which is so explicitly a Sabbat narrative that it involves the Witches ending up in the arms of the Warlock men, but like many faerie Sabbats no diabolism occurs. Although they do learn how to “throw the faerie stroke,” but here it is unequivocal that Witches are learning their skills from faeries who are not labeled demons. If we consider these links between the “Devil’s piper” or the “Devil as piper” as a faerie man, then the figure of Robin Goodfellow is strongly suggested by Style’s “Robin.” What we have in the form of Robin Goodfellow, or Puck, is a particular faerie figure who is connected over a wide area with teaching, piping or having an off-sider who pipes for Witches, and even possibly animal charming.

Just as there was a Puck (the other name for Robin Goodfellow), there was a Poucca of Wales, a Puca of Ireland and a Bucca of Cornwall, the alternative “Robin” as the name of a prominent faerie man might have been equally widespread in Britain and Ireland. Even the Welsh prophet and conjure man Black Robin (Robin Dhu) exhibits some Puck-like qualities suggesting he may be connected withthis figure. As of course does the English Robin Hood with his leveling trickster qualities and his almost exclusive Mary worship. If Robin is indeed the name for one well-known tutelary faerie who teaches Witches—not just the “white” ones—then the link between faerie familiars and the genesis of Witchcraft is quite explicit.

Given how clearly we can see British and Irish Witches learning their skills from faeries, it must have been very familiar to our forebears when they heard the “Watchers” had been the ones to teach Witchcraft to mankind. It seems increasingly obvious why the connection between faeries and fallen angels would have been forged and remained strong in Old Craft traditions, long after the threat of church persecution diminished. Dual faith observance, it seems, may have been about more than hiding the Craft in plain sight, but also to do with intrinsic intersections between certain aspects of the two stories, particularly between the Faerie Faith and some of the apocryphal material.

Given that the earliest testimony about a deep committed relationship with a familiar is Alice Kyteler’s “demon worship” of Robin Artisson, it might behoove us to more deeply explore demonology and whether we find any faerie-like characteristics in prominent demons. We have already noted earlier that Reginald Scot’s work draws together both faerie beings and demons without really specifying too much difference between the two. Like the powerful hobman Robin/Puck, the faerie woman Sibylla mentioned by Scot or as Sib by Shakespeare, lives inside a mountain teaching Witches all the way over in Italy and yet also emerges in England and Scotland.

Some faerie entities were so powerful that they had numerous Witch familiars and were linked to more than one location. Here the line between “faerie” and “God” or “Goddess” becomes very blurred. But in the Faerie Faith, which seems to display a continuous sliding scale of power, rather than clear distinctions between human, faerie and God, this is not to be thought unusual.

The Testament of St Cyprian the Mage by Jake Stratton-Kent discusses how the Goetic tradition and its demon-teeming grimoires are influenced by Witchcraft and folkore relating to the Wild Hunt. His reference to the Hunt is particularly interesting after Hogg’s poem and his phantom riders participating in the Witch’s Sabbat.

There are also many famous witching animals like toads, owls and black dogs among the forms the grimoire demons take and plenty of references to objects from European folklore, such as the hazel wand. So whilst demonology certainly overwrote the witchcraft narrative in certain ways, the realm of faerie and folk sorcery also colonised demonology in return, as Paul Carus explored in his History of the Devil, quoted above. Many of the darker faerie attributes—those connected with the Underworld, dark elf, Wild Hunt, nightmare or winter hag figures—became attached to demons and then back into Witchcraft.

The picture that begins to emerge for the intuitive observer is not a history with a universal “white sabbat,” associated with faeries and full of goodness and light, overcome later by a “black sabbat” imposed from above via demonology and persecution. What we see instead is the suggestion, the smallest echo, of an early Faerie Faith replete with all the characteristics of both, layered on by emerging demonology that was itself already colonized by folkloric sources. It seems as if the so-called “white sabbat” of faerie magicians that Henningsen postulates is actually just a different layer of Otherworldly experience, the “black demonic sabbat” having its place in relation to initiatory ordeals in particular and the dark elf beings who preside over such powers.”

—

Sounds of Infinity

10: ‘The Faerie as Witch’s Familiar’

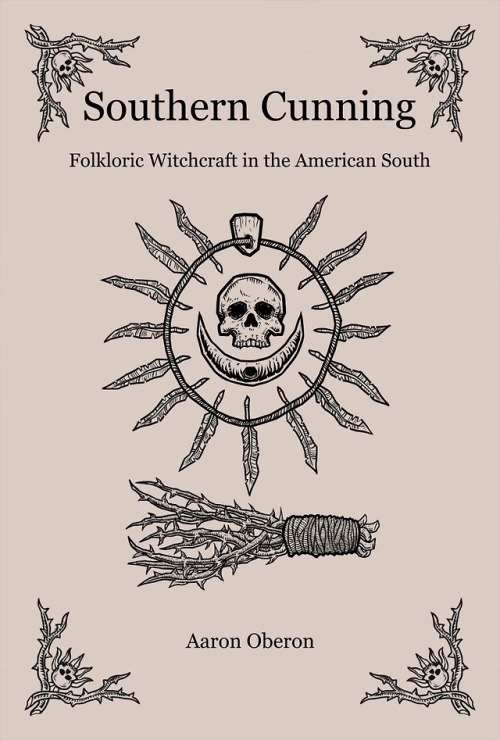

by Lee Morgan

Southern Cunning is now available for pre-order! I’m so excited to have this going out into the world and sharing something that has been such a labor of love. Pre-orders are immensely helpful for authors so give it a gander! Here are some of the early reviews for Southern Cunning

“Born of experience and lived practice, Aaron Oberon’s honest, warm and insightful exploration of Southern Cunning illumines an immersive journey from the crossroads through the stories, rites, tools and substances of an operative witchcraft rooted firmly in folkloric potency, the ways of spirits and the power of place.” - Gemma Gary, author of Traditional Witchcraft - A Cornish Book of Ways

“A straight-talking, easy to follow take on folkloric witchcraft from the South, rich in personal anecdotes and practical tips.” -Lee Morgan, author of A Deed Without a Name

“This is the sort of book I wish there were more of, because it connects the living magic of the past with the living magic of the present without getting stuck on problems of lineage, authentication, or secrecy. Southern Cunning will be a valuable addition to the library of anyone with an interest in folklore, magic, and witches with a Southern flavor.” -Cory Thomas Hutcheson, host of the podcast New World Witchery

Post link