#legends and odd things

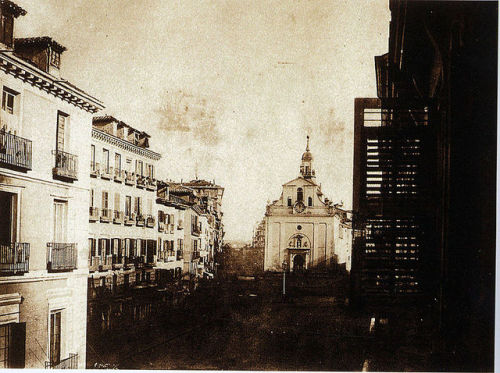

Madrid definitely has a thing with legends about beheaded people. The ghost which, according to legend, inhabited the church of San Ginés, is only one of them. Although there are references of a church of San Ginés in the city since the 12th Century, the current aspect of the building is more modern. After being partially demolished and rebuilt between 1641 and 1672, the church suffered several fires. The building as its known today is the result mainly of the reforms after these fires and a last intervention at the ending of the 19th Century… Leaving aside, of course, the restoration after the damage caused after the Civil War.

One night in 1353, or so the legend says, an old man (in certain version of the legend, a priest) was praying inside the church. Unfortunately that was the moment chosen by several bandits to the building and ransack the church’s treasure. When they realized they weren’t alone, the bandits egorged the poor man, with such violence that his head almost was separated from his body. Then they disappeared leaving the corpse there.

The crime left the neighbourhood shocked, especially since the ghost of a beheaded man started to appear at San Ginés, claiming revenge over his murderers. Night after night the ghost would appear, revealing at last the names of the bandits.

The story arrived to the King’s ears. Those of Pedro I, nicknamed the Cruel mainly by his enemies or the Just for those who were not. That depends on which side of the civil war which he lost against his half-brother Henry of Trastamara they were. The case is a group of men were said to be the guilty ones of the old man’s murder and arrested. Sentenced to death, they were pushed from a clift, just outside the city.

Did the beheaded ghost disappear then? Apparently yes. Or not, according to another story that tells how the ghost defended several homeless men who had taken refuge inside the church after being harassed by a group of vandals. While the latter were at the gates of San Ginés, somethingstarted to knock the door with such violence that the vandals ran away. As they were told by the (very alive this time) priest next morning, the church was totally empty that night, so no one, with perhaps the exception of our beheaded friend, could have made flee the vandals.

The ghost, if he’s still there, has been in good company until recent times with another particular inhabitant of San Ginés: the infamous stuffed crocodile which at some point during the 16th Century was laid at the Virgin’s feet and that it’s no longer there. No one knows where did the crocodile go. Rumors says that at some point during the last century the priest became annoyed because everyone entering the church went there not out of devotion, but just because they wanted to see a stuffed crocodile, so he just threw the thing away.

Urban legends of Madrid: The ghost of the naughty priest.

Sandwiched between two unremarkable appartament buildings, the last chalet standing in number 124 of Madrid’s Calle de Ayala (named after the writer Abelardo López de Ayala) hides an unedifying story behind its pretty façade, now painted in a discreet grey instead of its original yellow. For decades, as the legend goes, workers of what had become an office building were terrified by strange noises, laments, and the lights of the chalet ramdonly going on and off during the evening.

Number 124 (like other buildings in the same street) had been decades before a brothel, where a priest (other versions claiming he was a bishop) died suddenly while in company of one or several girls. Apparently it’s his ghost the one to blame for all the above mentioned nuisances, even if there are also rumours about two or three prostitutes dead in strange circunstances.

Photo F. Moreno. In that site there’s also mention to number 126, which seems to have been also host of a similar phenomenon. Not the naughty priest thing, but instead noises coming from a pub which has been closed for years.

Post link

Cirilo, the birds and the night visitors

If there’s a spot in Madrid charged with a somber backstory which could made it the perfect magnet for ghosts, then probably the Plaza Mayor is the place to be for human ghosts. And probably ghost birds too, given the story of the equestrian monument that presides it (there are no mention about ghost birds, though, which I find disappointing). This “main square” has seen auto-da-fés, executions, bullfights and three fires (1631, 1672 and 1790) with multiple victims. It’s not strange then that rumours about mysterious aparitions (inside or outside the buildings surrounding the square) abound.

Plaza Mayor’s “official” ghost is Cirilo, who apparently was executed there during the 17th Century. He’s not as popular as Ataúlfo or the ghosts of the Palace of Linares, but he has his little space in the city’s extended list of spectral inhabitants. Cirilo’s favourite activity is to equally scare tourists and madrileños. For the ghost, the fact that his victims are present at the square at certain hours of the night is reason enough. Cirilo and other unnamed ghosts are said to visit the housings nearby. Perhaps they hang near one of the square’s secondary entrances, in past times called Hell’s Alley (Callejón del Infierno, in Spanish). Thus named in remembrance of the 1672 fire. Since 1854, the street bears the somewhat less intriguing name of Arco del Triunfo (Triomphal Arch).

And what about the birds? Philip III’s statue, a masterwork by Gianbologna and Pietro Tacca, was, during centuries, a mortal trap for them. This was unintentional: the horse’s mouth had been left slightly open, so sparrows and other little birds were often trapped inside. Only in the 20th century, when after the proclamation of the Second Republic someone throw a little bomb against the statue and damaged it, was this discovered. When the monument was restored the house’s mouth was carefully sealed, so no other bird had to suffer the same fate again.

Photo by Sebastian Dubiel,Wikimedia commons.

Post link

Death comes to Mass.

Jerónimo de Barrionuevo, a writer from the Spanish Golden Age, maybe is not that known compared with the likes of Cervantes, Quevedo or Lope de Vega, but he left behind a long series of letters to the Dean of Saragossa, in which he penned a vivid portrait of daily life in Madrid during the 17th Century.

Barrionuevo’s letters were reunited in several volumes under the title of Avisos. One can find very juicy details, e.g., that day when a woman and her husband were found in bed together in unison with a friar (the friar seems to have been playing the tambourine at the same time). Or we have this strange story from February 1656, when a majordomo of the House of Alba found Death herself, under the appareance of a young and beautiful lady.

The scene takes place in the Church of Buen Suceso, then placed at the Puerta del Sol and demolished during the reform of the square in 1854. One of the servants (Barrionuevo precises he was one of high rank) of the Duke of Alba went to mass and found himself sitting near a extremely beautiful lady. From time to time he kept looking at her. At the end of the mass he approached her, discovering, to his horror, that now the lady’s face was that of Death herself.

The poor man lost conciousness, and had to be taken back home in a coach. Barrionuevo then claims the man died exactly twenty-four hours later. Of the mysterious lady, nothing else is said. Our writer then goes for a totally different story and tells the Dean how their Majesties (that is, Philip IV and his wife) plan to invite a whole crowd of ladies to the theater and then loose more than a hundred mice just to see what happens (their Majesties finally decided not to loose them, as Barrionuevo tells in his next letter)…

Post link

Once upon a time, in the 17th Century there was a little girl called Blanca Coronel who decided to save the little fishes from a pond near her father’s house. Berfore Mr. Coronel and his daughter lived there, their garden had been part of the state of a Priest, a certain Henríquez. The City Council, after Henríquez’s death, adquired his propiety, selling it by lots, since the city’s increasing population was in need of new homes. Henriquez had lived a long life and was found dead by his servants near to a fountain. The Priest’s Fountain (la Fuente del Cura) gave its name to the street, until little Blanca intervened.

The lot adquired by Mr. Coronel had a little pond, where fishes swam. But, as the works in the building went on, the level of water dropped and they started to die. Blanca did her best to rescue them: she tried to keep them alive in a bowl [I pretty much doubt that there was such a thing like a proper fishbowl in 17th Century Madrid but this is a legend after all] with clean, fresh water, but they died anyway, one by one, until only one was left. And it didn’t last. Blanca was devastated, so as a consolation her father carved a fish in their house’s façade. Blanca’s reaction is not recorded and the Coronel’s house has disappeared, but the carved fish is still there, and the street became known as Calle del Pez: the Street of the Fish. What we know about Blanca is that she later became a nun in the nearby Convent of San Plácido. Which has its own share of legends and scandals. Blanca, though, doesn’t seem to be directly involved in any of them. But that’s another story.

Urban legends of Madrid: Goyito, the ghost in the skyscrapper.

Inaugurated in 1930, the Telefónica Building (seen in the background) was Spain’s first skyscrappers and one of the first in Europe. Taking inspiration in New York’s architecture, a Spanish baroque touch was added in the main façade and ornaments. It had been conceived as the siege of Spain’s national telephone company; from there, Hemingway, Dos Passos or Saint-Exupéry send their reports of the Spanish Civil War. It’s not strange that the skyscrapper was a target of bombings, which, in the words of his architect Ignacio de Cárdenas, only scratched the colossus’ skin. The colossushad lived somber moments before, like for example the suicide of Ana Cubillo, one of the Telephone Company’s workers, who jumped to her death from floor 7th in 1934.

And then you have Goyito, the building’s ghost. During years, there had been rumours about workers of the company meeting him. But information about Goyito is quite contradictory. Is our ghost a little boy or an elder gentleman (with monocle!)? Does he appears in floor 9 or floor 13? Or in both of them? It remains unclear.

Post link

Like all cities in the world do, Madrid has its share of famous crimes. However, there’s a house in the very heart of the city that seems a magnet for them. One could argue that the entire street is, indeed, prone to tragedy and violence. But number 3 concentrates the higher amount of murders. The most known took place in may 1962, when a taylor murdered his entire family in the third floor, before taking his own life. But it wasn’t the first one, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Even if it didn’t happen inside the house, it must be noticed that a man was killed just in front of the main entrance, in 1915.

The first crime which took place in the building was the murder of the shirtmaker Felipe de la Breña in 1945. He was found dead days later on his bed, in his appartment of the first floor. Lying on his bed, his head bloodied, and still held a lock of hair in his hand. The conclusion was that he had surprised (or been surprised by) a burglar who had hit him in his head, causing his death.

On May the 1st, 1962, Mr. José María Ruiz Martínez, a taylor who had his workshop near the house killed his wife and his children. He hit her with a hammer and later stabbed his children, one by one. From a balcony he cried that he loved his family and that he had killed them in order to avoid killing certain bastards. He then asked for a priest, claiming that he wouldn’t open the door to anyone else and that he now could kill himself. The priest arrived then and tried to negotiate with him, urging the taylor to repent and surrender to police, but Mr. Ruiz carried out his threat, shooting himself.

In 1964, a young woman in the first floor made a macabre discovery: the corpse of a dead baby hidden in a drawer. It turned out to be her sister’s Pilar own son. Pilar was single and had given birth alone, immediatly killing the newborn to avoid disgrace (being a single mother in Franco’s Spain turned a woman in a social pariah).

As noticed above, the street itself seems to concentrate a high rate of violence: a woman attacked her husband’s lover with vitriol, there were several people ran over different vehicles, suicides, and if all this wasn’t enough, one of the most infamous serial killers in Spain used to hang with his friends near there.

The series El Ministerio del Tiempo dedicated an episode to the crimes of the house in Antonio Grillo street, but changing the adress to Antonio Grilo, 10.

Urban legends of Madrid: The Ghost Actress of the Lara Theatre

Named after his founder and patron, Cándido Lara, the Lara Theatre was built in 1879. It was one of the many little theatres that abounded in Madrid during the last decades of the 19th Century. The Lara has known hard times, especially after the Spanish Civil War, this time not because of the sequels of war themselves but because Mrs. Milagros Lara (Cándido’s daughter and heiress)’s last will was to demolish it. Closed in 1985, it was reopened almost one decade later. Unlike other similar theatres, the Lara manages to survive.

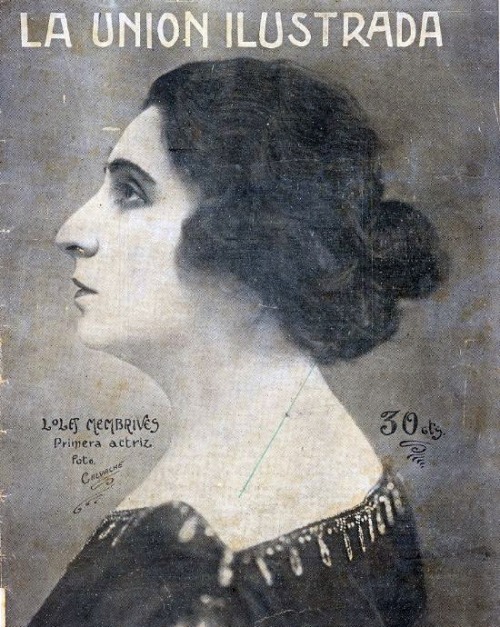

Apart from its “secret” passages that aren’t a secret for anyone, legend wants the theatre is inhabited by the ghost of Lola Membrives (1888-1969), an Argentinian actress who spent part of her career in Spain, starring in plays by Lorca, Benavente or Machado, and playing the great roles from the classic Spanish repertoire, from Calderón to Lope. Membrives later returned to her hometown, Buenos Aires, where a theatre is named after her. But apparently part of the actress’ soul remained in Madrid. Lola’s ghost likes to sing from her dressing room when the theatre is empty and closed to public, and there are people who will swear her voice can be heard from the stage. It is said, also, that she will be furious if she doesn’t like the expositions that are held in one of the theatre’s halls.

Fun fact: the ghost of Membrive’s colleague and contemporary Margarita Xirgu is said to haunt the Romea Theatre in Barcelona.

Post link

Among the streets that disappeared with the creation of the Gran Via, one of the most narrow (in fact, it was the narrowest street in the city) was the Dog Alley, or in Spanish, el Callejón del Perro. According to legend the alley’s name comes from a legendary black mastiff from the 15th Century, the loyal guardian of the secrets of Enrique de Villena, nicknamed The Necromancer.

The Marquis of Villena had royal blood in his veins. Born in Torralba de Cuenca in 1384, skilled mathematic, chemister and philosopher, he owned, according to legend, an apparently modest shed in this alley, mainly destined to house his books, writings and instruments. A ferocious guardian dog watched over the shed.

The mastiff was an excelent guardian, keeping unwanted visitors out of Villena’s shed. That alone would have been enough to make the dog feared. But, given his master’s reputation as a necromancer, the mastiff soon became the subject of rumors in the city. It was said that this new Cerberus guarded the Hell’s gate. It was said, more often, that the dog had the evil eye. Those who dared to get closer to the shed were invariably cursed… by the dog.

Needless to say, this ghost story doesn’t have a happy ending, although there are several versions about how the mastiff met his end. In one version, the dog was killed after attacking a crossbowman. In a more heroic variation of the legend, the animal died defending his master’s books when they were condemned to be burnt. The culprit of his death is still a crossbowman in this second version.

Later, the residents of the alley still claimed that the shadow of Villena’s dog appeared every single night, howling and attacking those who dared to enter in the alley. It also was said that the mastiff’s shadows covered the façades of the diminute street. With time, the alley took the name of the Dog, although by then the faithful ghost had disappeared…

Inaugurated in 1871 and nowadays a nightclub, the Theater Eslava has its own ghost, that of the playwright and politician Luis Antón del Olmet, killed there in 1923 [you can find the date 1922 on the Internet too, but press archives exist for a reason]. The murderer was a colleage and former friend of Mr. Olmet, Alfonso Vidal Planas. One day, as the rehearsal of one of Olmet’s plays, El Capitán sin Alma (The Soulless Captain) was going on, the two men, who were talking in one of the theater’s rooms, had a heated argument. Was it due to literary rivalry, or to another kind of jealousy? There were rumours about a woman involved with the two men…

An actress, Mrs. Corona, heard them from her dressing room. When Vidal yelled at Olmet: ‘I’ll kill you, here or in front of your wife, it doesn’t matter!’ she ran for help, but it was too late: a gunshot was heard and, when the theather’s personal and several of the actors entered the room, they found Olmet laying on a sofa. Vidal was beside the victim, still holding his gun. I have killed him. He was a scoundrel, and he had wronged me, were Vidal’s first words.

Olmet was carried to the hospital where he died that same day. Vidal later claimed that he had killed the playwright in self-defense ( according to his version, Olmet had tried to strangle him).

Image source (by Tamorlan at Wikimedia Commons)

Post link