#literature meta

I was thinking recently about how some “reparative” interpretations of difficult or troubling texts end up turning every work of fiction into a mouthpiece for the same uplifting and reassuring vision of the world, and I think one of the most interesting examples of this phenomenom is the story of the reception of I. L Peretz’s short story “Bontshe Shvay”.

The story revolves around the character of “Bontshe the silent”, a kind of anti-Job and a figure of absolute passivity in front of injustice. The first half describes his insignificant life, spent in absolute silence (”he was born in silence ; he died in silence ; he was buried in silence”) ; and the second is centered on his judgment in the after-life.

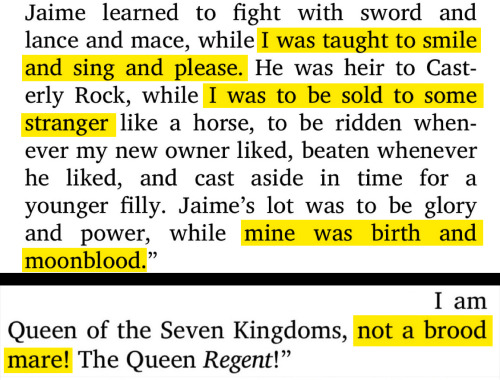

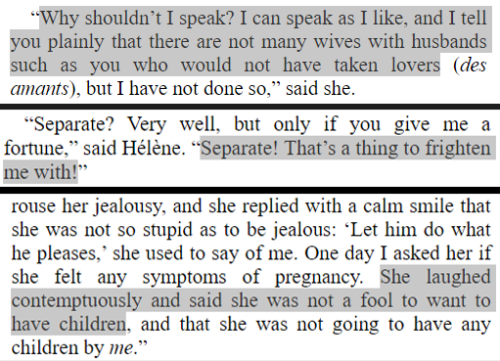

Peretz (Poland, 1851-1915), an activist and one of the most prominent figures of Yiddish literature, was very close to the Bund (the main secular Jewish socialist party of the Russian Empire) at the time he wrote that text. A lot of people have thus been reading it, since its publication, as a socialist denunciation of absolute disempowerment and alienation. Others, however, have turned it into a narrative of sainthood, interpreting Bontshe as a figure of exemplary humility.

I think it’s a very good illustration of how -idependently from what the work actuallypresents as admirable or not- its political and moral impact largely depends on its interpretations.In case anyone be interested, here is a large excerpt of the text (translation by Golda Werman, full version here) :

Here on earth the death of Bontshe Shvayg made no impression. Try asking who Bontshe was, how he lived, what he died of (Did his heart give out? Did he drop from exhaustion? Did he break his back beneath too heavy a load?), and no one can give you an answer. For all you know, he might have starved to death.

The death of a tram horse would have caused more excitement. It would have been written up in the papers; hundreds of people would have flocked to see the carcass, or even the place where it lay. But that’s only because horses are scarcer than people. Billions of people!

Bontshe lived and died in silence. Like a shadow he passed through this world.

No wine was drunk at Bontshe’s circumcision, no glasses clinked in a toast; no speech to show off his knowledge was given at his bar mitzva. He lived like a grain of gray sand at the edge of the sea, beside millions of other grains. No one noticed when the wind whirled him off and carried him to the far shore.

While Bontshe lived, his feet left no tracks in the mud; when he died, the wind blew away the wooden sign marking his grave. The gravedigger’s wife found it some distance away and used it to boil potatoes. Do you think that three days after Bontshe was dead anyone knew where he lay? There was not even a gravestone for a future antiquarian to unearth and mouth the name of Bontshe Shvayg one last time.

A shadow ! No mind, no heart, preserved his image. Nothing remained of him at all. Not a trace. Alone he lived and alone he died.

Were not humanity so noisy, someone might have heard Bontshe’s bones as they cracked beneath their burden. Were the world in less of a hurry, someone might have noticed that Bontshe, a fellow member of the human race, had in his lifetime two lifeless eyes, a pair of sinkholes for cheeks, and, even when no weight bent his back, a head bowed to the ground as if searching for his own grave.

Were men as rare as horses, someone would surely have wondered where he disappeared to.

When Bontshe was brought to the hospital, the corner of the cellar he had called his home did not remain vacant, because ten men bid for it at once; when he was taken from the hospital ward to the morgue, twenty sick paupers were candidates for his bed; when he was carried out of the morgue, forty men killed in the fall of a building were carried in. Think of how many others are waiting to share his plot of earth with him and well may you wonder how long he will rest there in peace.

He was born in silence. He lived in silence. He died in silence. And he was buried in a silence greater yet.

******

But that was not how it was in the other world. There Bontshe’s death was an occasion.

A blast of the Messiah’s horn sounded in all seven heavens: “Bontshe Shvayg has passed away! Bontshe has been summoned to his Maker!” the most exalted angels with the brightest wings informed each other in midflight. A joyous din broke out in paradise: “Bontshe Shvayg - it doesn’t happen every day!”

Young, silver-booted cherubs with diamond-bright eyes and gold-filigreed wings ran gaily to greet Bontshe when he came. The flapping of their wings, the patter of their boots, and the merry ripple of laughter from their fresh, rosy mouths echoed through the heavens as far as the mercy seat, where God Himself soon knew that Bontshe Shvayg was on his way.

At the gates of heaven stood Father Abraham, his right hand outstretched in cordial welcome and the most radiant of smiles on his old face.

[…]

The defense counsel said: - “At last, one dizzy, wet spring evening, he arrived in a great city. He vanished in it like a drop of water in the sea, though not before spening his first night in jail for vagrancy. And still he kept silent, never asking why or how long. He worked at the meanest jobs and said nothing. And don’t think it was easy to find them.

“Drenched in his own sweat, doubled over beneath more than a man can carry, his stomach gnawed by hunger, he kept silent!

“Spattered with the mud of city streets, spat on by unknown strangers, driven from sidewalk to staggers in the gutter with his load beside carriages, wagons, and tram cars, looking death in the eye every minute, he kept silent![…]

“He never even raised his voice to demand his meager wage. Like a beggar he stood in doorways, glancing up as humbly as a dog at its master. “Come back later!” he would be told - and like a shadow he was gone, coming back later to beg again for what was his.

“He said nothing when cheated, nothing when paid with bad money.

“He kept silent!”

“Why, perhaps they mean me after all”, thought Bontshe, taking heart.

“Once”, continued the counsel for defence after a sip of water, “things seemed about to look up. A droshky raced by Bontshe pulled by runaway horses, its coachman thrown senseless on the cobble-stones, his skull split wide open. The frightened horses foamed at the mouth, sparks shot from under their hooves, their eyes glittered like torches on a dark night - and in his seat cringed a passenger, more dead than alive.

“And it was Bontshe who stopped the horses!

“The rescued passenger was a generous Jew who rewarded Bontshe for his deed. He handed him the dead driver’s whip and made him a coachman, found him a wife and made him a wedding too, and was even thoughtful enough to provide him with a baby boy…

“And Bontshe kept silent!”

“It certainly sounds like me”, thought Bontshe, almost convinced, though the still did not dare look up at the tribunal. He listened as the counsel went on:

”He even kept silent in the hospital, the one place where a man can scream.

“He kept silent when the doctor would not examine him without half a ruble in advance and when the orderly wanted five kopecks to change his dirty sheets. He kept silent as he lay dying. He kept silent when he died. Not one word against God. Not one word against man.”

”The defense rests!”

[…]

The judge said: “My child, there, in the world below, no one appreciated you. You yourself never knew that had you cried out but once, you could have brought down the walls of Jericho. You never knew what powers lay within you.

“There, in the World of Deceit, your silence went unrewarded. Here, in the World of Truth, it will be given its full due.

“The Heavenly Tribunal can pass no judgment on you. It is not for us to determine your portion of paradise. Take what you want! It is all yours, all yours!”

Bontshe looked up for the first time. His eyes were blinded by the rays of light that streamed at him from all over. Everything glittered, glistened, blazed with light: the walls, the benches, the angels, the judges. So many angels!

He cast his dazed eyes down again. “Truly?” he asked, happy but abashed.

“Why, of course!” the judges said. “Of course! I tell you, it’s all yours. All heaven belongs to you. Ask for anything you wish; you may choose what you like.”

“Truly?” asked Bontshe again, a bit surer of himself.

“Truly! Truly! Truly!” clamored the heavenly host.

“Well, then,” smiled Bontshe, “what I’d like most of all is a warm roll with butter every morning.”

The judges and angels hung their heads in shame. The prosecutor laughed.

Hamlet dies before an audience, harping on the audience present to him, and his consciousness of himself is immortalized by his consciousness of them.That is not an option for us, not merely because we cannot command an audience, since no one’s position is relevantly different from mine; but because, since no one’s position is relevantly different from mine, to convert others into an audience is to further the very sense of isolation which makes us wish for an audience. Its treatment of this fact is what makes King Lear so threatening, together with its consequent questioning of what we accept as natural and legitimate and necessary. The cost of an ordinary life and death, of insisting upon one’s one life, and avoiding one’s own cares, has become the same as the cost of the old large lives and deaths, requires the same lucidity and exacts the same obscurity and suffering. This is what Lear knows for the moment before his madness; it is the edge Gloucester’s blinding has led him to. Immediately after Lear’s prayer (III, iv, 28–36), he gives himself up to the tempest in his mind and to the storm which is to destroy the world; Gloucester’s thoughts, just after his prayer (IV, i, 66-71), turn to Dover and its cliff. That is, successful prayer is prayer for the strength to change, it is the beginning of change, and change presents itself as the dying of the self and hence the ending of the world. The cause of tragedy is that we would rather murder the world than permit it to expose us to change. Our threat is that this has become a common option; our tragedy is that it does not seem to us that we are taking it. We think others are taking it, though they are not relevantly different from ourselves. Lear and Gloucester are not tragic because they are isolated, singled out for suffering, but because they had covered their true isolation (the identity of their condition with the condition of other men) within hiddenness, silence, and position; the ways people do. It is the enormity of this plain fact which accompanies the overthrow of Lear’s mind, and we honor him for it.

But we will not abdicate. As though this was his answer, while ours will come later, on another occasion, from outside. And it does look, after the death of kings and out of the ironies of revolutions and in the putrefactions of God, as if our trouble is that there used to be answers and now there are not. The case is rather that there used not to be an unlimited question and now there is. “Human reason has this peculiar fate that in one species of its knowledge it is burdened by questions which, as prescribed by the very nature of reason itself, it is not able to ignore, but which, as transcending all its powers, it is not able to answer.” (Preface to the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, opening sentence.) Hegel and Marx, as we know, found this fate not in human reason but in human history. Hegel then denied the distinction between them, Marx thought they could at last be distinguished. Hegel thought both were finished, Marx thought both could now begin. The world whistles over them. We cannot hear them.

Stanley Cavell, “The avoidance of love. A reading of King Lear”, inMust We Mean What We Say.