#mail coaches

Fast mail coaches were introduced in 1784, with recognized mail routes springing up across the land soon after. There were two types of fast coach upon the road, and with the exception of the wealthy, who traveled in their own carriage or by post-chaise, and of the very poor, who used wagons or slow night coaches, all passenger traffic was done by mail or stage coach. Stage and mail coaches were alike in build, carrying four inside passengers and ten or twelve outside. Mail bags were piled high on the roof, and luggage was carried in large receptacles called boots at either end of the vehicle. The box seat by the coachman, for which an extra fee was charged, was considered the most desirable and was frequently occupied by someone interested in horse flesh. Mail coaches, which were subsidized or owned by the Post Office, were painted uniformly, the lower part of the body being chocolate or mauve, the upper part as well as the fore and hind boots black, and the wheels and under carriage a vivid scarlet. The Royal arms were emblazoned on the doors, the Royal cipher painted in gold upon the fore boot, and the number of the vehicle on the hind boot. The panels at each side of the window were embellished with various devices, such as the badge of the Garter, the rose, shamrock or thistle.

The departure of the mails was one of the most exciting sights in London. On its outward journey, each coach collected passengers from whatever inn the vehicle was horsed at and then dashed ‘round at 8 p.m. to St. Martin’s le Grand to collect the mail. Coaches were called by name to receive their bags, and the crash of the lid of the boot locking down on the special mails was the signal for each coach to speed away. Fast stage and mail coaches made their journeys in about the same time. It took five hours to travel from London to Brighton, two more to Southampton, seventeen hours to Exeter, nineteen to Manchester and twenty-one to Liverpool. This worked out to an average speed of 10 miles an hour. The coaches, besides galloping against each other, were always running against the clock, for lateness was punished by heavy penalties and loss of credit. The half-thoroughbred horses were kept in peak condition and during their stage of seven or eight miles were worked at fever pitch. The steadier wheelers were meant to act as a check upon their leaders, but more often than not the driver gave the wheelers their heads and the whole team sped along at a gallop.

In truly severe weather, the sufferings of the outside passengers was terrible. Once, when the Bath mail changed horses at Chippenham one March morning, two of the outside passengers were found frozen to death, a third dying later. Post boys were frequently lifted out of their saddles near the point of death. The winter of 1836 was one of the worst on record, with Christmas storms closing all coach roads for several days. On December 26th, the Manchester, Holyhead, Chester, and Halifax mails were all stuck in snow drifts at Hockley Hill, near Dunstable, within a few yards of one another, and throughout the country, stories of overturned coaches and dogged heroism on the part of coachmen and guards were recounted. In one instance, a guard, leaving his snowbound coach, carried out instructions by taking the mails forward on horseback. Nine miles farther on he sent the horse back but pushed on himself. Next morning he was found dead a mile or two up the road, with the mail bag still tied round his neck.

Change of horses at each fresh stage was made quickly. Hostlers and stable boys were allowed a minute in which take out the old horses and harness up a fresh team, though some could manage the job in fifty seconds. Seats on a coach had to be secured in advance at the inn from which it started or where it stopped on the road. The traveler’s name was entered into a book and half the fare taken as a deposit. The fares by stage coach worked out to 2 ½ to 3d a mile outside, 4-5d a mile for inside passengers. Mails coaches were dearer, averaging from 4 1/2d to 5d for outsides, 8-10d for insides.

The coachman wore beneath his coat a crimson traveling shawl topped by a long waistcoat of a striped pattern, and over that a wide-skirted green coat ornamented with large brass buttons. Usually he wore on his head a wide-brimmed, low-crowned brown hat. He wore knee cord breeches, painted top boots, and a copper watch chain. The real responsibility for the coach rested with the guard who, in the case of mail coaches, had the added care of guarding the letter bags. In their red coats, with the gleaming brass horn at the ready, they collected fares from those who joined the coach on the road, saw that the schedule was kept to, and were entrusted with the execution of commissions. In case of accident, the guard looked after the mails and the passengers, carrying the former by horse and arranging for a fresh coach for the latter if necessary. They were accustomed to journeys of up to 120-150 miles at a stretch and received about 10s a week in wages. Inside passengers were supposed to tip the guards 2s 6d, the outsides 2s, and the guard collected further tips for handling luggage or running errands.

Travelling post chaise was decidedly the favored means. The chaise was a light and comfortable vehicle with two, or more commonly four, wheels drawn by two or four horses ridden by post boys. For great haste, four horses with two postilions were used. As with a mail coach, the horses were changed at stages. There was room for only two passengers in a post-chaise, but most carriages had a dickey, or platform, at back for a groom. Principal turnpike gates out of London were found in Knightsbridge at the corner of Gloucester Road, in Kensington at the corner of Earls Court Road, at Marble Arch, Notting Hill, King’s Cross, City Road near Old Street, Shoreditch, Commercial Road, Kennington Gate, and three more in the Old Kent Road.

An important London coaching inn was the Golden Cross in Charing Cross, near Nelson’s Column before 1830, when it was moved to face Craven Street. Coaches left here bound for Gloucester, Cheltenham, South Wales, Chester, Liverpool, Hastings, Dover, Stroud, Brighton, Halifax, and other points. The Saracen’s Head stood at the top of Snow Hill, next to St. Sepulchre’s Church, with coaches leaving for many parts of England and Scotland. During the eighty years before its demolition in 1868, the inn had been kept by members of the Mountain family, the most prominent being Sarah Ann Mountain, who carried on after her husband’s death in 1816. She dispatched thirty coaches from her inn each day and set a record with her Tally Ho! to Birmingham. She also built coaches for sale at 110 - 120 guineas each. The Tally Ho! served Canterbury, Liverpool, and Birmingham, and was one of nine coaches on the London to Birmingham route. Its team of four horses was changed at each of the ten stops made between London and Birmingham. The Tally Ho! normally made the 109-mile trip in eleven-and-a-half hours, traveling at an average speed of 9.5 mph. During the famous London to Birmingham race, which took place on May Day, 1830, the Tally Ho! made coaching history, setting a record by covering the route in seven-and-a-half hours, travelling at an average speed of 14.5 mph. It should be noted that the coach carried no passengers during the race.

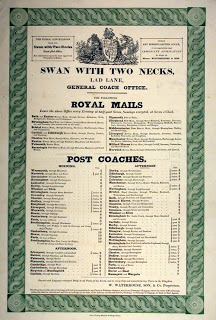

The Swan With Two Necks was the hub of much activity during the 17th and 18th centuries, serving London as a coaching, parcel, and wagon office. The name is derived from Swan with Two Nicks, the nicks being the mark by which the birds of the Vintner’s Company were identified. The inn was a terminus for northbound coaches, and stood at the corner of Aldermanbury, where the Guildhall was and is located, with the Wax Chandler’s Hall being on the south side of the street. The inn was demolished in 1845 when Lad Lane, St. Anne’s Lane, Maiden Lane, and Cateaton Street were all widened during the building of Gresham Street.

William Chaplin, the “Napoleon of coach proprietors,” was born at Rochester, Kent, in 1787, son of a coachman-proprietor, and he himself started off driving the Dover Union. Marriage to the sister-in-law of James Edwards, “one of the largest proprietors on the Kentish routes,” proved useful. He and Edwards allied in many ventures in Kent. He came to horse more and more coaches until, by 1827, he owned between three- to four-hundred animals and the Spread Eagle, Gracechurch Street. By 1835, he owned twelve-hundred horses and the Swan with Two Necks. In 1838, he horsed sixty-eight coaches with eighteen-hundred horses, employing two-thousand men. He also acquired the Cross Keys and the White Horse, Fetter Lane, and opened the Spread Eagle coach office in Regent Circus. Chaplin was said to have had “immense energy, an equable temperament and great sagacity,” and also, “a very good knowledge of the animals he governed as well as the bipeds with whom he was associated”. Nevertheless, Chaplin one day had a run in with George Denman, toll collector at Kensington Gate, who issued Chaplin a toll ticket bearing the improper amount. A fight broke out during which Denman took hold of Chaplin’s horses, prompting him to use his whip upon the toll keeper. Chaplin was later fined 12s and court costs. As with most well-to-do businessmen, Chaplin was known to grumble about the actual profits he made, stating in 1827, “I have not a shadow of a doubt that, were the coaching account of the nation kept regularly, the whole is decidedly a loss and the public have the turn.”

Source: http://onelondonone.blogspot.com/2010/03/english-mails-part-two.html