#18th century history

I will likely re-post this every few weeks.

New call for research articles for the scholarly journal Eighteenth-Century Fiction, McMaster University: http://ecf.humanities.mcmaster.ca/call-for-articles/

Please also see the ECF home page:

http://ecf.humanities.mcmaster.ca/

ReadEighteenth-Century Fiction journal online via institutional subscription at Project MUSE:

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/eighteenth_century_fiction/

Post link

One of Georgiana’s numerous fashion achievements was her invention and popularization of what was known at the time as the Picture Hat. When she sat for Gainsborough in 1783, Georgiana wore this heavenly haberdashery, which she had designed herself. After the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the hat became all the rage. Numerous women went straight to their milliners, requesting “the picture hat” that they has seen at the Royal Academy. Whether they actually liked the over-sized feathered and ribboned black hat or were only imitating the fashionably elite is not known, but this hat resurfaced in the following century among Victorian women, now called the “Gainsborough Hat”.

Below are some pictures of this fabulous hat.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/picture-hat.html

Earl Grey is the name of an absolutely delicious black tea blended from Indian and Ceylon tea leaves with a dash of bermagot oil. Legend has it that the eponymous earl, Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, got the blend off of a Chinese mandarin after Lord Grey kindly saved said mandarin’s life.

However, history has it that Charles Grey was kind of a dick when he was younger.

Charles Grey had a precocious talent and a predilection for older women and power. When he was first elected at the age of 22 to the House of Parliament in 1786, he lost no time in befriending the leaders of the Whig party. One of those leaders was the political hostess Georgiana Cavendish, the Duchess of Devonshire. By having the tenacious persistence that would put a cactus in a drought to shame, and an emo obsession with the Duchess that would make Stephanie Meyer’s Edward Cullen seem well-adjusted, Lord Grey managed to convince the Duchess of Devonshire (who was rather lonely, as her husband was a cold fish who preferred his dogs to human beings and who was dickishly sleeping with her best friend) into having an affair. In the late 18th century this was not at all uncommon. It was even quite expected. Aristocrats started up affairs to stave off boredom, glean governmental secrets, pay off debts, or gain political power. As long as you were discreet, you were good to go. However, the keyword was “discreet,” and there Lord Grey and Her Grace the Duchess of Devonshire showed themselves to be completely illiterate.

While the Duke of Devonshire was in London, the Duchess was in Bath with her sick sister, Harriet, Countess of Bessborough. Charles Grey was in Bath too and was very publicly seen to go in and out of the Duchess’ house. Gossip spread, Lord Grey impregnated the Duchess, and someone wrote a letter to the Duke of Devonshire to come to Bath immediately.

This was bad.

The Duke was in a towering rage about his wife’s indiscretion (it was impossible to pass of the child as his, as they had been living apart for most of the year), and threatened to divorce the Duchess and keep her from ever seeing her three beloved children again if she didn’t give up Grey and Grey’s baby immediately. Grey was also in a towering rage, and demanded that the Duchess give up her other children and social position and marry him. The Duchess couldn’t bear to give up her dearly beloved children off of the Duke or her position as the political hostess of the Whig party/the arbitrator of Georgian fashion/one of the most popular and influential political figures in Great Britain, and so was forced to give up Grey’s baby by “going abroad for her sister’s health”, i.e. giving birth in France, where hopefully no one would notice she was pregnant, and then shipping the baby off to Grey’s parents to raise. Grey was furious, refused to speak with her again, blamed her for the entire mess, and married someone else without even bothering to tell her. The Duchess was speechless with grief when she found out by reading it in a newspaper.

Later on, Grey, who had fifteen children with his wife Mary Ponsonby, found monogamy not to his taste and had a torrid affair with another Whig political hostess, Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s second wife, Hecca.

So, Earl Grey. Kind of a dick.

Fun Fact: Earl Bessborough, Harriet’s (the Duchess’ sister) husband, escorted Georgiana and Harriet to France. During the entire time, Harriet’s husband had no idea that the Duchess of Devonshire was pregnant. Absolutely none. However, Earl Bessborough was not known for his powers of observation. Later on, his wife had two children by the love of her life, Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, and her husband did not notice she was pregnant either time.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/earl-grey-kind-of-dick.html

Superstitions abound from many cultures and many eras, and continue to flourish around the globe even in the most technologically advanced societies. The startling array of old wives’ tales, saws, and warnings that survive to this day are a reflection of many preoccupations, ranging from largely historical fears about the welfare of animals and portents of coming weather, to psychologically-telling omens of marital discord, mistrust of new innovations, and magical ways of probing what the future holds.

Since superstitions played a large part in the historical era, I thought I might do a series of blogs about the role different superstitions played in various societies. Perhaps this information will serve as a source of research for you, the reader/writer.

Let’s begin with “abracadabra”. The word “abracadabra” is a magical invocation that is associated chiefly with stage conjurers and pantomime witches, but in fact has a long history as a cabalistic charm. The charm was said to have special powers against fevers, toothache, and other medical ailments, as well as to provide protection against bad luck. Sufferers from such conditions were advised to wear metal amulets, or pieces of parchment folded into a cross and inscribed with the word repeated several times, with the first and last letter removed each time until the last line read just “A”. According to the thinking behind the charm, the evil force generating the illness would decrease as the word grew shorter. Once the charm had proved effective (after a period of nine days), the wearer was instructed to removed the parchment cross and to throw it backwards into an eastwards flowing stream before sunrise.

Such charms were, according to Daniel Defoe in his Journal of the Plague Year (1722), widely worn in London in the 17th century as protection against the plague. Simply saying the word out loud is also said to summon up strong supernatural forces, hence its use by contemporary stage performers and entertainers throughout the West.

Well, this is certainly a curious if not entertaining belief. Stay tuned for a fascinating journey in to the world of superstitions.

Source: http://historicalhussies.blogspot.com/2009/01/superstition.html

Funny things tended to happen to Pitt the Younger when he was, well… younger. It is possible that this was because Pitt, who was a notorious drinker, could out-drink most university students and often led his college friends in drunken routs. At one point in time, Pitt instigated a practical joke by stealing a friend’s top hat during a house party at William Wilberforce’s villa in Wimbleton, cutting the hat to pieces, and then planting the pieces in the garden.

This amateur historian is sure the joke made more sense when drunk.

However, one of the most amusing of his university experiences had to be when he was invited to the country estate of his friend Henry Bankes, along with William Wilberforce and a number of others. Pitt readily accepted this invitation, as he was a younger son without a country estate, and London (this was at the beginning of the industrial revolution and also at a point where London was one of the most populated cities on the planet) was said to be deadly in the summer. While they were there, Pitt and his friends engaged in some grouse shooting.

No record remains of what they shot, except that the short-sighted Wilberforce took aim at Pitt and nearly shot him in the head by mistake.

Grouse shooting later came back to haunt Pitt the Younger; in 1797, his bill to introduce some regulation and social security for child laborers failed when the MPs decided they’d rather debate grouse-shooting instead.

Wilberforce got the worst end. For the rest of his life, his friends teased him for having taken “a shot a greatness” and missed.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/pitt-younger-goes-grouse-shooting.html

First things first, here are all those elusive postal details you’ve been seeking. Before the introduction of the prepaid penny post (Post Office Act of 1765) and adhesive stamps (6 May 1840), postage was usually collected from the recipient. Rather than paying in advance, one paid on delivery. In order to save their correspondents paying postage, some people had their letters “franked”. A frank was the signature of a Member of either House of Parliament, who had to write both the address on the envelope as well as his signature in his own hand. Thus postage was free.

Envelopes had been developed in the 1830s, but did not catch on until the Great Exhibition of 1851, when Jeremiah Smith displayed his gummed envelopes. Still, the use of envelopes in correspondence was not general until well into the 1860s, with most people preferring the old fashion of folding over the sheet of paper and fastening the flaps with a wafer, a little disc of gum and flour, which was moistened and pressed down with a seal. Quill pens were used long after steel nibs had been introduced. Quills soon lost their point and needed cutting with a sharp “pen knife,” so the art of cutting a nib was one of the first things taught at school.

The penny post routes operated six days a week in most cases. Rates of postage at a uniform penny were lower than those charged by most private carriers, some of whom charged fees as high as 4d to take letters from the nearest post town. Many private posts charged for both letters delivered and those collected for onward transmission by the general post. The official penny post charged only for letters delivered, a system which allowed for posting boxes to be provided at certain points. Letters were delivered to any house on the penny post route, and in most villages receiving houses were set up where people in outlying areas could collect their mail. In 1830, the letter rates for the penny post were 4d for 15 miles, 5d for 20 miles, and thence according to a sliding scale to 1s for a limit of 300 miles. A letter from London to Liverpool cost 11d, to Bristol 10d, to Aberdeen 1s 3d, and to Glasgow 1s 2d. Packages weighing an ounce paid four times the ordinary rate, and for every quarter of an ounce in excess an additional sum was charged. Letters sent to addresses within the same post town were delivered free of charge. In the late 1880s, commercially-produced picture postcards became all the rage and the Post Office instituted a half-penny fee for the handling of these.

A late posting fee was sometimes charged and was meant to deter letters from being posted at times inconvenient to official duties, this usually being a penny. Private postal boxes were available but not in widespread use at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1837, the Bromley postmaster had six subscribers from whom he received a guinea each. The use of such boxes was explained in The Second Report on Postage (1838): “Persons having Private Boxes enjoy generally the advantage of receiving their letters as soon as the window is open and the letter-carriers despatched, but which means, those Subscribers who reside at any distance from the post office obtain their letters so much earlier than they would do by the ordinary Delivery; they have also the opportunity of ascertaining at once whether there are any letters for them, and are usually allowed credit by the Postmaster, accounts being kept of their postage.”

The Postmaster could also realize extra revenue by the sale of money orders. From 1798 on, the Money Order Office was run by three partners, including Daniel Stow, Superintendent President of the Inland Office. Originally, money orders were offered in order to enable soldiers and sailors to send funds home to their families. In 1861, the Post Office Savings Bank was opened, with millions opening small savings accounts over the next forty years.

The Twopenny Post served London and its suburbs. There were six collections and deliveries daily in London, and three in the suburbs, letters being posted at various receiving offices during the daytime, while the last collection was made by a postman who went through the streets ringing a bell. There were two kinds of postmen in London, the General, who delivered the post from all parts of the country, and the Twopenny Postman, who had only to do with local mail. Both wore much the same style of uniform – a scarlet coat, and a shining top hat adorned with a gold band.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, postmasters had also been innkeepers due to the fact that they were responsible for finding post boys and horses, providing stabling, etc. Once recognized mails came into being, this was no longer necessary, and it was felt that inns provided little security for the mail bags. In October 1792, the Post Office declared itself against the appointment of innkeepers, as separate rooms for postal business were rarely provided and business might be conducted in the bar. By March 1836, only one post town in the entire country had an innkeeper as postmaster. More common were post offices run by druggists, stationers, grocers, news agents, and booksellers. Women could be appointed postmistresses or allowed to take over the concern upon the death of their husbands. Of the twenty-nine Kentish post towns in March 1836, four had postmistresses. One of these was the bustling Ramsgate office, the salary of which was roughly 178 pounds per annum. When a postmistress married, it was the ruling of the Post Office that she must give up the appointment, but it could be transferred to her husband. At Faversham, the widow of Mr. Plowman, the late postmaster, took over upon his death, but in 1800 she married Andrew Hill, who became postmaster in her place. After Mr. Hill died in July of the same year, Sara was reappointed.

Source: http://onelondonone.blogspot.com/2010/03/low-down-on-english-post.html

This 1791 print is entitled “THE LUBBER’S HOLE… alias… the Crack’d JORDAN” because Gillray believed wholeheartedly in CAPITALIZATION. The speech bubble is a nonsensical nautical cry of glee (an articulate “Yar! Yar! Yar!”) because Gillray had no freaking clue how the hell sailors talked.

The subjects of the painting are the actress Dorothea Bland, who went by Mrs. Jordan (Mr. Jordan was what one would call a figure of speech) and was famous for doing cross-dressing comedic roles at the Drury Lane Theatre, and the Duke of Clarence, the third son of George III and a member of the Royal Navy, as can be seen with the blue and gold coat hanging on the wall.

Jordan is, unfortunately, a slang word for “chamber pot”. Mrs. Jordan was well-known for her vulgarity, and the number of men who made her their mistress and later tired of her, hence her representation as a cracked chamber pot on legs. By far the most famous of her… suitors… was the Duke of Clarence, who gave her ten children and dickishly told her she’d get a pension only if she gave up the stage. Mrs. Jordan did so, but was forced to return to the stage when one of her sons-in-law fell grievously into debt. Her pension vanished and she died in poverty in France, as did a number of Regency celebrities. Fleeing to France in poverty was basically the 18th century equivalent of going into rehab.

The Duke of Clarence later became a king of England (King William IV), but most people thought he was a really crappy sailor, too distracted by impregnating Mrs. Jordan to actually do anything of consequence. The fact that he did not take part in the Napoleonic wars because he had fallen down some stairs drunk and broken his arm, thus rendering himself incapable of command and convincing the Lords of Admiralty that he was too dumb to live, did not do him any favors. Gillray calls attention to this by making the Duke of Clarence go through the lubber’s hole. It was a naval tradition to get up to the crow’s nest by climbing the diagonal netting up to 50 feet above the deck instead of just climbing up the mast and pulling oneself through a hole (the lubber’s hole) to the platform of the crow’s nest. Real men, you see, don’t follow safety precautions.

However, by the time he became William IV, everyone was royally pissed off at his elder brother George IV, who had massively overspent his income, gone completely mad, and horrified most of British society with his hedonism and his lechery, and William IV was welcomed with open arms. William IV was better received as King of England than Duke of Clarence (the Duke of Wellington said that he “he had done more business with King William in ten minutes than he had with George IV in as many days”). Despite his conservative opinions, his reign saw a large number of reform bills, the total abolition of slavery, a weakening of the generally conservative House of Lords, a welfare bill, and the establishment of child welfare laws. This came, of course, with a weakening of monarchical influence.

Since the House of Hanover was known to have porphyria and a genetic history of stupidity, this could be seen as a good thing.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/lubbers-hole.html

As some blogs tend to do, The Gossip Guide will begin to feature some weekly hotness. Although these sexy ladiez have been in the ground a couple of centuries, that doesn’t mean they don’t deserve their place to be ogled in the blog sphere. The tart who receives the first honor of this position is one close to my heart: Grace Dalrymple Elliott.

Yeah, I know. At first glance she looks kind of like your grandma, but once you get past the interesting shade of powder and the charcoaled eyebrows, Grace was like a supermodel, or at least tall enough to be one. During the height of her celebrity she was known as Dally the Tall. Unlike most supermodels today, she was not crazy and a smart cookie. She was a child bride of this fat, ugly doctor in London who divorced her after, it is alleged, he caught her sleeping with a hot rake. Meow! She went on to have affairs with The Prince of Wales and the Duke d'Orleans, among others. She spent most of her life in France, and gave us some of the most reputable accounts of the French Revolution, which she saw firsthand. Grace narrowly escaped the guillotine after months in French prisons, even having her hair sheared off in preparation. Although she was arrested just to be arrested, she was a firm royalist, had helped Marie Antoinette with correspondence during the Revolution, and may have even met the future Empress Josephine during her imprisonment. Obviously she also had strong connections with other hot tarts! Plus, you kind of have to like her just based on the fact that she wore low cut gowns for her formal portraits.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/tart-of-week.html

Below you have Gainsborough’s stately portrait of a Prime Minister in perfect control of both himself and his elegant setting (note the neatness of Pitt’s attire and how the line of the pen matches the line of his right arm – very orderly is the young Mr. Pitt) and to the upper left you have Gillray’s less than flattering print of Pitt the Younger as a “An Excrescence; – a Fungus; – alias – a Toadstool upon a Dung-hill”, as Gillray believed Pitt’s power to stem solely from rotten royal favor. Note the rosy nose, which is a pot-shot at Pitt’s habit of drinking three bottles of port a day.

William Pitt the Younger became Prime Minister of Great Britain at 24, a position he held (except for two years) until his death, which not only makes him the youngest Prime Minister in history, but also one with the second-longest term in office. Many people, including Pitt himself, who was an MP at 21 and Chancellor of the Exchequer at 23, were quite surprised when George III tried to bully Pitt into taking office in 1782 just as Pitt was about to complete his gentlemanly education by taking a Grand Tour of the Continent with two of his friends, William Wilberforce (who spearheaded the British Abolition movement) and Edward Eliot (who later married one of Pitt’s sisters).

Being bullied by a monarch is enough to put anyone into a tizzy, which is probably why none of these gentlemen thought to get a letter of introduction. In the 1780s, letters of introduction served not only as a passport into a country, but a passport into society. The three gentlemen managed to secure a letter to a certain Monsieur Coustier in Rheims just before they had to leave England.

In the words of Mr. William Wilberforce: “From Calais we made directly for Rheims, and the day after our arrival dressed ourselves unusually well, and proceeded to the house of Mons. Coustier to present, with not a little awe, our only letters of recommendation. It was with some surprise that we found Mons. Coustier behind a counter distributing figs and raisins. I had heard that it was very usual for gentlemen on the continent to practice some handicraft trade or other for their amusement [Marie Antoinette liked pretending to be a milkmaid, herself], and therefore for my own part I concluded that his taste was in the fig way, and that he was only playing at grocer for his diversion; and, viewing the matter in this light, I could not help admiring the excellence of his imitation; but we soon found that Mons. Coustier was a ‘véritable epicier,’ and that not a very eminent one.”

They thus spent what one can assume was an extremely boring week at Rheims, since their friend the grocer did not even sell figs to the local aristocracy and could not introduce them to anyone. Since they spoke no French (Wilberforce had slacked off at Cambridge; Eliot had studied law, not languages; and Pitt had studied classical languages like Greek and Latin, which, though helpful for becoming a famous Parliamentary orator, was of no practical value in Rheims) and kept to themselves, they were almost arrested as spies.

Fortunately for them, the bishop of Rheims knew Pitt the Elder, the late Earl of Chatham/Pitt’s now-dead father, and took them in as guests, causing Mr. Wilberforce to note: “N.B. Archbishops in England are not like Archeveques in France; these last are jolly fellows of about forty years of age, who play at billiards, &c. like other people”.

Sage words, Mr. Wilberforce, sage words.

Thus concludes the first part of what will be an admittedly long series on Funny Things That Happened to Pitt the Younger.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/blog-post.html

The above image is one of my favorite depictions of her Grace. It is a satirical image from 1784, which happened to be a very big year in the Duchess’ life. Not only did she have her first child after years of painful miscarriages, but she also became notorious for her part in the 1784 Westminster elections. In fact, this seemed to be the thing she became the most known for, besides, of course, being a leader of fashion. She became the first woman to canvass for a political leader, hers being Charles James Fox. The image shows Georgiana on the left, brandishing a staff with the head of Fox on it, identifiable by the fox tails. She holds in her other hand an image of the Prince of Wales, another Whig figurehead. In the right panel we see her cuckolded husband tending to their child.

Of course, the image is meant to be more insulting to the Duke, who probably couldn’t care less about his public image. Although it’s meant to be equally insulting to the Duchess of Devonshire, I think it fails in this. From an 18th century viewpoint, we see a lady out of control, and therefore whose sexuality is out of control as well. From a contemporary standpoint, we see an awesome image of feminine power and liberty.

As an introduction to Georgiana, we have a perfect first impression. This nonchalant image captures what the stuffy portraits cannot portray: a personality that stands out in a sea of powdered coiffures.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/devonshire-amusement.html

Elizabeth Farren was an Irish actress of humble origins. She excelled at her art and was even dubbed “the queen of comedy” by Horace Walpole, the social authority of the time. Given that Elizabeth was the starlet of Drury Lane Theater, the title was probably not flattery. She excelled at playing aristocratic ladies, even portraying Lady Teazle in Sheridan’s School of Scandal, a part based upon The Duchess of Devonshire.

It was likely these parts that got Edward Smith-Stanley, 12th Earl of Derby’s attention. The earl fell in love with Elizabeth despite the fact that his wife, Elizabeth Hamilton, was still very much alive. The secret affair was once again very public in satirical prints and therefore a widely followed affair. When Lady Derby died, the earl wasted no time making Elizabeth his wife (and the new Lady Derby). They were married two months after his first wife’s death. The couple continued to be ridiculed in satires, with Elizabeth portrayed as the tall and skinny gold-digger, and the earl as short and squatty. They amused and inspired satirical artists throughout the rest of their marriage – a typical celebrity union.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/tart-of-week-elizabeth-farren.html

Here are a few historical tidbits about a man who received very little formal education, the Romantic poet William Blake.

Blake was an odd character whom all the other Romantic poets found bewildering, and whom Wordsworth and Coleridge called “crazy Blake”. Coleridge, reviewing Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, found fault with Blake’s hand-drawn illustrations, in particular with the “I don’t know whatness of the countenance, as if the mouth had been formed by the habit of placing the tongue, not contemptuously, but stupidly, between the lower gums and the lower jaw”. Coleridge also disapproved of “the mood of the mind”, i.e. the supposed sanity of the poet. Robert Hunt, a critic of the time, was highly upset that “the ebullitions of a distempered brain [were] mistaken for the sallies of genius… [in the] admirers of William Blake, an unfortunate lunatic, whose personal inoffensiveness secures him from confinement and, consequently, of whom no public notice would have been taken, if he was not forced on the notice and animadversion of the Examiner, in having been held up to public admiration by many esteemed amateurs and professors as a genius in some respect original and legitimate”.

This amateur historian personally thinks that the best line from Hunt’s review is as follows:

“The praises which these gentlemen bestowed last year on this unfortunate man’s illustrations… have, in feeding his vanity, stimulated him to publish his madness more largely.”

The fact that Blake amped up the crazy in order to get people who annoyed him to leave him alone probably did not help this impression.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/02/oh-that-crazy-blake.html

Without getting into too much detail (because this is another post with babble potential), I’d like to touch upon the imagery of Charlotte Corday, who definitely wins the prize for “Most Spartan” Frenchwoman, but I’d like to look at it from the English perspective. To review, Charlotte was the broad who took matters into her own hand when the executions in the French Revolution became too numerous. Placing blame on Jean-Paul Marat for the out of control killing sprees, Charlotte assassinated Marat with a butter knife in his bathtub. Well, maybe not a butter knife, but she she did buy a kitchen knife right beforehand to do the job. She was, of course, punished with the original execution of death by guillotine.

This, of course, made her a martyr. The French despised her for her actions. A man even lifted her freshly severed head from the guillotine basket to slap her cheek. The English, on the other hand, idolized the murderess. As can be seen in this Gillray print, Corday is one of the few women to be portrayed in a positive light by the satirical artist. Her depiction is very similar to those of Britannia, a rare compliment for those not of English origin. Don’t you just love how in this depiction, Charlotte address the assembly as “wretches”? Plus, I doubt Gillray ever put so much time into making a hairdo look nice as he did with this print. It should also be noted how incredibly un-French Charlotte looks. She looks more… hmm… British? Her depiction is notably in the British vogue.

The British, who have a tradition of enjoying a good rebellion (unless it is against them), felt France crossed the line with the execution of Louis XVI. Charlotte became, for them, a symbol of liberty, the exact thing France was fighting for. The French disagreed with this viewpoint and felt it was Marat, the guy who died taking a bubble bath, who was the true martyr.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/gossip-from-france-charlotte-corday.html

Duff Cooper, Talleyrand’s biographer, on the difference between Talleyrand and Fouché was that for the former “politics meant the settlement of dynastic or international problems discussed in a ball-room or across the dinner-table; for Fouché the same word meant street-corner assassination, planned by masked conspirators in dark cellars”.

Charming individuals, no?

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/talleyrand-and-fouche.html

This is taken from Frederick the Great’s early journals:

“I admire [Voltaire’s] eyes, so clear and piercing… I would kiss his eloquent lips, 100 times.”

This came as something of a surprise to Voltaire when he found out, particularly considering Voltaire was, at that time, madly in love with Emilie du Chatelet, a renowned physicist. They were on the outs at the time of the trip because Emilie was actually much smarter than Voltaire, which had sent Voltaire into a passion when they discovered it (Emilie placed above Voltaire in an essay contest for the Academie des Sciences).

Fortunately, though Frederick the Great wrote that most evenings he and his court full of young men “lost money at cards, danced till we fell, whispered in each other’s ears, and when that had shifted to love, began other delicious moves,” Voltaire talked about Emilie a great deal and was off the hook.

Less fortunately, he was still irritated with Emilie for being smarter, and his name-dropping turned to mocking quips and complaints about her, which did not amuse Emilie when word got back to her.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/frederick-great-on-voltaire.html

Voltaire visited Frederick the Great as a French spy, something which he took no pains to conceal. Most of Europe then thought of Frederick the Great as a floofy monarch who didn’t pose a threat to anyone because his claim to fame had been trying to run off with his boyfriend and then getting caught. His father then threw Frederick the Great into prison, where the guards mocked Frederick for playing his flute and reading French literature.

Surely Frederick wouldn’t catch on. The fact that most of Europe was pretty pissed at Voltaire for his satirical poetry and the mission was pretty much given as a “get-the-hell-out-of-my-country-if-you-won’t-stop-writing-about-me” sort of trip by Louis XV did not daunt Voltaire either. Thus, he set off from France in high spirits, going so far as to grandly inform a sentry guarding Westphalia, “I am Don Quixote!”

The sentry apparently did not speak any language other than German, and smiling and nodding, let Voltaire pass.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/moment-with-voltaire.html

Fast mail coaches were introduced in 1784, with recognized mail routes springing up across the land soon after. There were two types of fast coach upon the road, and with the exception of the wealthy, who traveled in their own carriage or by post-chaise, and of the very poor, who used wagons or slow night coaches, all passenger traffic was done by mail or stage coach. Stage and mail coaches were alike in build, carrying four inside passengers and ten or twelve outside. Mail bags were piled high on the roof, and luggage was carried in large receptacles called boots at either end of the vehicle. The box seat by the coachman, for which an extra fee was charged, was considered the most desirable and was frequently occupied by someone interested in horse flesh. Mail coaches, which were subsidized or owned by the Post Office, were painted uniformly, the lower part of the body being chocolate or mauve, the upper part as well as the fore and hind boots black, and the wheels and under carriage a vivid scarlet. The Royal arms were emblazoned on the doors, the Royal cipher painted in gold upon the fore boot, and the number of the vehicle on the hind boot. The panels at each side of the window were embellished with various devices, such as the badge of the Garter, the rose, shamrock or thistle.

The departure of the mails was one of the most exciting sights in London. On its outward journey, each coach collected passengers from whatever inn the vehicle was horsed at and then dashed ‘round at 8 p.m. to St. Martin’s le Grand to collect the mail. Coaches were called by name to receive their bags, and the crash of the lid of the boot locking down on the special mails was the signal for each coach to speed away. Fast stage and mail coaches made their journeys in about the same time. It took five hours to travel from London to Brighton, two more to Southampton, seventeen hours to Exeter, nineteen to Manchester and twenty-one to Liverpool. This worked out to an average speed of 10 miles an hour. The coaches, besides galloping against each other, were always running against the clock, for lateness was punished by heavy penalties and loss of credit. The half-thoroughbred horses were kept in peak condition and during their stage of seven or eight miles were worked at fever pitch. The steadier wheelers were meant to act as a check upon their leaders, but more often than not the driver gave the wheelers their heads and the whole team sped along at a gallop.

In truly severe weather, the sufferings of the outside passengers was terrible. Once, when the Bath mail changed horses at Chippenham one March morning, two of the outside passengers were found frozen to death, a third dying later. Post boys were frequently lifted out of their saddles near the point of death. The winter of 1836 was one of the worst on record, with Christmas storms closing all coach roads for several days. On December 26th, the Manchester, Holyhead, Chester, and Halifax mails were all stuck in snow drifts at Hockley Hill, near Dunstable, within a few yards of one another, and throughout the country, stories of overturned coaches and dogged heroism on the part of coachmen and guards were recounted. In one instance, a guard, leaving his snowbound coach, carried out instructions by taking the mails forward on horseback. Nine miles farther on he sent the horse back but pushed on himself. Next morning he was found dead a mile or two up the road, with the mail bag still tied round his neck.

Change of horses at each fresh stage was made quickly. Hostlers and stable boys were allowed a minute in which take out the old horses and harness up a fresh team, though some could manage the job in fifty seconds. Seats on a coach had to be secured in advance at the inn from which it started or where it stopped on the road. The traveler’s name was entered into a book and half the fare taken as a deposit. The fares by stage coach worked out to 2 ½ to 3d a mile outside, 4-5d a mile for inside passengers. Mails coaches were dearer, averaging from 4 1/2d to 5d for outsides, 8-10d for insides.

The coachman wore beneath his coat a crimson traveling shawl topped by a long waistcoat of a striped pattern, and over that a wide-skirted green coat ornamented with large brass buttons. Usually he wore on his head a wide-brimmed, low-crowned brown hat. He wore knee cord breeches, painted top boots, and a copper watch chain. The real responsibility for the coach rested with the guard who, in the case of mail coaches, had the added care of guarding the letter bags. In their red coats, with the gleaming brass horn at the ready, they collected fares from those who joined the coach on the road, saw that the schedule was kept to, and were entrusted with the execution of commissions. In case of accident, the guard looked after the mails and the passengers, carrying the former by horse and arranging for a fresh coach for the latter if necessary. They were accustomed to journeys of up to 120-150 miles at a stretch and received about 10s a week in wages. Inside passengers were supposed to tip the guards 2s 6d, the outsides 2s, and the guard collected further tips for handling luggage or running errands.

Travelling post chaise was decidedly the favored means. The chaise was a light and comfortable vehicle with two, or more commonly four, wheels drawn by two or four horses ridden by post boys. For great haste, four horses with two postilions were used. As with a mail coach, the horses were changed at stages. There was room for only two passengers in a post-chaise, but most carriages had a dickey, or platform, at back for a groom. Principal turnpike gates out of London were found in Knightsbridge at the corner of Gloucester Road, in Kensington at the corner of Earls Court Road, at Marble Arch, Notting Hill, King’s Cross, City Road near Old Street, Shoreditch, Commercial Road, Kennington Gate, and three more in the Old Kent Road.

An important London coaching inn was the Golden Cross in Charing Cross, near Nelson’s Column before 1830, when it was moved to face Craven Street. Coaches left here bound for Gloucester, Cheltenham, South Wales, Chester, Liverpool, Hastings, Dover, Stroud, Brighton, Halifax, and other points. The Saracen’s Head stood at the top of Snow Hill, next to St. Sepulchre’s Church, with coaches leaving for many parts of England and Scotland. During the eighty years before its demolition in 1868, the inn had been kept by members of the Mountain family, the most prominent being Sarah Ann Mountain, who carried on after her husband’s death in 1816. She dispatched thirty coaches from her inn each day and set a record with her Tally Ho! to Birmingham. She also built coaches for sale at 110 - 120 guineas each. The Tally Ho! served Canterbury, Liverpool, and Birmingham, and was one of nine coaches on the London to Birmingham route. Its team of four horses was changed at each of the ten stops made between London and Birmingham. The Tally Ho! normally made the 109-mile trip in eleven-and-a-half hours, traveling at an average speed of 9.5 mph. During the famous London to Birmingham race, which took place on May Day, 1830, the Tally Ho! made coaching history, setting a record by covering the route in seven-and-a-half hours, travelling at an average speed of 14.5 mph. It should be noted that the coach carried no passengers during the race.

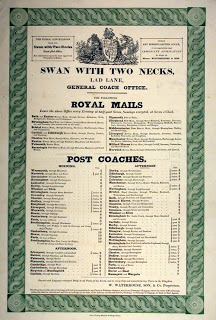

The Swan With Two Necks was the hub of much activity during the 17th and 18th centuries, serving London as a coaching, parcel, and wagon office. The name is derived from Swan with Two Nicks, the nicks being the mark by which the birds of the Vintner’s Company were identified. The inn was a terminus for northbound coaches, and stood at the corner of Aldermanbury, where the Guildhall was and is located, with the Wax Chandler’s Hall being on the south side of the street. The inn was demolished in 1845 when Lad Lane, St. Anne’s Lane, Maiden Lane, and Cateaton Street were all widened during the building of Gresham Street.

William Chaplin, the “Napoleon of coach proprietors,” was born at Rochester, Kent, in 1787, son of a coachman-proprietor, and he himself started off driving the Dover Union. Marriage to the sister-in-law of James Edwards, “one of the largest proprietors on the Kentish routes,” proved useful. He and Edwards allied in many ventures in Kent. He came to horse more and more coaches until, by 1827, he owned between three- to four-hundred animals and the Spread Eagle, Gracechurch Street. By 1835, he owned twelve-hundred horses and the Swan with Two Necks. In 1838, he horsed sixty-eight coaches with eighteen-hundred horses, employing two-thousand men. He also acquired the Cross Keys and the White Horse, Fetter Lane, and opened the Spread Eagle coach office in Regent Circus. Chaplin was said to have had “immense energy, an equable temperament and great sagacity,” and also, “a very good knowledge of the animals he governed as well as the bipeds with whom he was associated”. Nevertheless, Chaplin one day had a run in with George Denman, toll collector at Kensington Gate, who issued Chaplin a toll ticket bearing the improper amount. A fight broke out during which Denman took hold of Chaplin’s horses, prompting him to use his whip upon the toll keeper. Chaplin was later fined 12s and court costs. As with most well-to-do businessmen, Chaplin was known to grumble about the actual profits he made, stating in 1827, “I have not a shadow of a doubt that, were the coaching account of the nation kept regularly, the whole is decidedly a loss and the public have the turn.”

Source: http://onelondonone.blogspot.com/2010/03/english-mails-part-two.html

Gentle readers, this amateur historian is quite pleased to announce yet another series, entitled “Voltaire Takes on the Universe: Voltaire Wins”.

The title, I should hope, is self-explanatory.

To begin with, we must start with the 23-year-old Voltaire, who was then going by the name Francois-Marie Arouet and was merely a minor poet. Someone had recently published some extremely subversive verses about the sexual escapades of Phillippe d'Orleans, who was serving as regent of France until Louis XV was old enough to rule on his own.

Arouet, who was rumored to be one of the possible authors of the poem, got into a discussion of said poem in the Parisian inn where he was living. Arouet mysteriously asked one of his new friends, i.e. a random guest in the inn, if he liked the poem, and boasted that though he, Arouet, was very young, he had, in fact, written it and written many more like it.

His new friend turned out to be a police spy.

Arouet went to the Bastille.

While he was there, he befriended his guards and formed an instant dislike for his head inquisitor, Monsieur Ysabeau. Ysabeau asked Arouet for any and all subversive poems. Arouet said he had no knowledge of said poems (which was actually true, as he hadn’t yet written any) and then “gave in” and said he’d left them at the inn. When Ysabeau failed to find them, Arouet feigned a fit of temper and “admitted” to throwing them down the toilet.

Ysabeau was forced to open up the sewage drain near the inn where Arouet had been staying, much against the wishes of the rest of the inn and all the people living around it. Ysabeau ought to have listened to the protests of Arouet’s neighbors. The drain was made of old bricks and mortar, and collapsed as soon as Ysabeau tried to inspect it more closely. The sewage spewed forth, ruining everything in the cellars of the inn (the inn-keeper later got compensation for the loss of his entire collection of beer and wines) and forcing Ysabeau to pick through the collected waste in search of the poems.

As Ysabeau wrote in his formal report, “It appears M. Arouet, with his active imagination. only pretended to have thrown away [the documents]… to create unnecessary work.”

While this was going on, Arouet wrote his first famous play, an adaptation of Oedipus that became the theatrical success of the decade. While his eleven-month jaunt in the Bastille had been unpleasant, the lack of other occupation forced him to finish his play, and this play earned him popularity with audiences and critics alike. Philippe d'Orleans, apparently feeling Arouet (who had now chosen the pen name Voltaire) had learned his lesson, told him to keep up the good work, and gave him a gold watch and a large annual subsidy.

Voltaire thanked Philippe d'Orleans for paying for his food, but begged the regent to never again chose his lodgings.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/voltaire-takes-on-universe.html

The actress, poet, and author known as Perdita in her celebrity life was born Mary Darby, and at the tender age of 16 she married Tom Robinson, the bastard child of some rich guy. What Mary is most known for is her very public secret affair with the Prince of Wales, as well as her acting career. Both, despite her celebrity from them, were actually very brief. She was the prince’s first big love and he would write her impassioned love letters (which he signed “Florizel” and addressed to “Perdita” based on the play he was introduced to her in), which she blackmailed him with later when she needed some cash. When the teenage prince grew bored of their very public affair, he promptly replaced her with Grace Dalrymple Elliot, a rival tart.

“A Correspondent says that Dally the Tall gave a superb fete last night at her house near Tyburn Turnpike, in consequence of the Perdita’s departure for the Continent, whose superior charms have long been the daily subject of Dally’s envy and abuse.“

-The Morning Herald, 19 Oct. 1781

Mary was not only a foe of the other tricks of the town. She also rivaled the Duchess of Devonshire in her ability to start new fashion trends.

The second half of her life was extremely opposite to the extravagance of the first half. She was permanently separated from her super lame husband (believe me, SUPER lame) and devoted her life to her writings. She became paralyzed from the waist down in an impassioned act of love for the true love of her life, the super dreamy Banastre Tarleton. Their relationship lasted many years before his family (who hated Mary) finally got him to marry some teenager, leaving Mary a bitter, bitter (already feminist) author. She was very devoted to her art and hung out with only the coolest authors, such as uber-cool chick, Mary Wollstoncraft. However, she will eternally be remembered as Perdita, the dame who robbed the sweet prince of his virginity… probably.

Source: http://georgianaduchessofdevonshire.blogspot.com/2008/05/tart-of-week-mary-perdita-robinson.html

This print is pretty self-explanatory. Regency gowns simply don’t flatter every figure.

Compare Gillray’s take on the new fashions of the late 1790s with Boilly’s, where a dedicated follower of fashion (a merveilleuse) is mistaken for a prostitute because of the general skimpiness of her attire.

In the 1790s, fashion took a complete 180 from the poufs and panniers associated with Marie Antoinette. The French Republic wished to complete change French culture, and what better medium than fashion? Since the National Assembly wanted to build a republic the likes of which had only been found in ancient Rome, tailors and dressmakers took their cues from ancient Roman statues, which meant high waists; long, trailing drapery; and simpler, curlier hairstyles.Since the French set the fashion, England followed, even though for most of the period when empire waist dresses were popular, England and France were engaged in a series of long and vicious wars against each other.

Fashion, apparently, is the one import that continues despite naval blockades and Russian winters.

Source: http://gillraysprintshop.blogspot.com/2009/01/following-fashions.html