#manyōshū

Today is one of those happy occasions where I actually have a photo of the place mentioned in the poem(s) I am going to translate/discuss… and even with a somewhat appropriate natural phenomenon (fog trailing across the peak) - although no river in sight. Regardless, this is in the Yoshino Mountains in early April 2007, when I took a day trip down to see the famous cherries. Those cherries are not quite as famous yet in the period of MYS, so there’s nothing about them in these poems, which really only feature Yoshino due to it being the site of the cremation of the maiden for whom these elegies were composed. Nevertheless the cherry blossoms trees scattered throughout the mountain are what make Yoshino still a part of the cultural imaginary in Japan, and that was the inspiration for my trip (well that and Heian literature), but next time I’ll have to remember to think of the poor drowned Izumo no otome while I’m there (hopefully later this year!).

溺死出雲娘子火葬吉野時柿本朝臣人麻呂作歌二首

Two verses by Kakinomoto no Asomi Hitomaro, upon the cremation in Yoshino of Izumo no wotome, who had drowned

山際従 出雲兒等者 霧有哉 吉野山 嶺霏(雨+微)

山の際ゆ出雲の子らは霧なれや吉野の山の嶺にたなびく

yama no ma yu/idumo no kora pa/kiri nare ya/yosino no yama no/mine ni tanabiku

From amongst the mountains/the girl from Izumo/is she now the mist?/that now on Mt Yoshino/trails across the peak?

八雲刺 出雲子等 黒髪者 吉野川 奥名豆颯

八雲さす出雲の子らが黒髪は吉野の川の沖になづさふ

yakumo sasu/idumo no kora ga/kurokami pa/yosino no kapa no/oki ni nadusapu

Myriad clouds thrust into the sky/the girl from Izumo/her black tresses/now float about in the pools/of the Yoshino river.

This is the first drowned maiden verse that I know of in MYS, although it doesn’t give much of a story other than to tell us that Hitomaro is composing at the funeral of a girl who drowned. But elegies for drowned maidens, and the tales of drowned maidens, are a persistent theme throughout the collection, and there seems to have been a certain aesthetic appeal to them, for they persist into Heian literature, albeit in different forms and generally more fleshed out (Unai no otome reappears in Yamato monogatari, and then you have Ukihime of the Genji Uji chapters, who is perhaps the most famous - although she survives). Women who cast themselves into the river, at the mercy of the tide, when faced with no other options, seem to have been a literary trope, but probably more than that - this was probably the “elegant”/”appropriate” way for a woman to die, when she needed to. Usually, this is portrayed as her choice - she chooses to seize control of her own fate and cast herself into the water; the fact that her death is later aestheticized by poets is a separate matter. She certainly doesn’t do it for them. In most cases that I know of where female suicide is aestheticized, however, it is because she is faced with an impossible situation in life, one which usually involves having to choose between two men and being unable to do so (not because she is conflicted, necessarily, but moreso because choosing one over the other or vice versa will result in negative repercussions beyond merely a scorned suitor - such as causing conflict within one’s group/village, or with another family/group/village). Her choice to sacrifice herself to avoid the negative ripples that might result from acting in life, is seen as beautiful - and being swept away by the waves, helpless, is somehow a method of death befitting that sort of sacrifice - admittedly, of course, this is all in the view of the male poets of the age. I am in no way endorsing this, mind you - simply noting this is a literary trope common from this time.

Here we don’t really get any background on Izumo no otome, other than that the manner in which she died was drowning, and she did so in the Yoshino River (information which we can garner from the second poem). We know she is then cremated on Mt. Yoshino, where Hitomaro imagines that the mist trailing over the peak is the smoke from her pyre (and therefore her, herself - a very similar notion with poem #428 in my previous post - girl = smoke from her fire = mist, with no real distinction or leaps of logic in between necessary). The fact that the drowned maiden was already a trope at this time, however, allows us to extrapolate and guess her story in some way mirrors the others (indeed, there is actually no direct mention of her having taken her own life here - we might think it was an accidental death, if it were not for the whole literary matrix that had already formed around the figure of the drowned maiden).

The first banka for this poor girl from Izumo (modern Shimane), who drowns so far away from home in Yoshino (near Fujiwara/Nara), begins with an epithet for Izumo (as does the second), “yama no ma yu.” Both “Yama no ma yu” and “Yakumo sasu” play on the name “Izumo” itself, which means “emerging clouds” - so in the first case, the clouds are emerging from between the peaks, and in the second, myriad clouds are being thrust up into the sky. This leads into the girl’s name, Izumo no otome (”The Izumo Maiden”), as we are not actually in Izumo here, but this use of makura kotoba, while decorating her name and honoring her home, also contrasts sharply with the “Yoshino” that appears in the fourth ku in both poems - and reminds us that the maiden was in a foreign land, far from home, when she died. Like the corpse that Hitomaro encounters by the wayside in poem #426, who had “forgotten his home” and died alone, far away, we get the sense that Izumo no otome died a lonely death. She’s just a young girl (”kora”) but tragically meets her end alone in a foreign land (politically, by this time, Izumo had been integrated into Yamato’s sphere of influence, but was likely still somewhat culturally distinct - as the Izumo no kuni fudoki would suggest - and her presence in the Nara area may have in fact been a political one, to cement ties been the Yamato center and Izumo - this would certainly explain a court poet such as Hitomaro’s presence at her funeral). Neither poem really seems to have a sense for who she is, either - Hitomaro certainly grieves for her death, but not really for her - it’s clear he probably didn’t know her personally, and there seems to be a good amount of distance as he’s viewing her (as smoke, and then as her hair floating in the river [good old synecdoche allowing him to talk about her corpse without actually talking about it]). He views her in much the same way he views the corpse from 426 - a body that has suffered a tragic end, but not necessarily anything more than that.

These two poems are very similar in terms of both structure and content - they mourn the maiden from a detached, even aestheticized point of view. The makura kotoba they use for Izumo is different, but the second ku is identical between the two; the first sees her in the scenery, the smoke from her pyre becoming the mist trailing over the mountains - the second sees her as part of the scenery, and brings us back to the moment and circumstances of her death in a way quite unsettling for a funeral, but perhaps important, to remind those present of the circumstances of the tragedy, and probably perhaps to ensure that her death is seen as a beautiful one, despite the pathos of her end, so young and in a foreign, far off place.

There are certainly more interesting banka out there - these are not the most exciting or emotive of even those I’ve looked at in volume 3 so far, but I think they are important for how they touch upon the drowned maiden motif and for how we begin to see death being aestheticized, rather than merely mourned, something which continues into Heian literature. Older banka focus on the biting pain of grief and the process of mourning - #427 is all about denial, for instance - but the step to making death beautiful, to making death some literary, is interesting. Perhaps this comes out of not knowing the girl in life, and merely composing as part of the ritual, as Hitomaro is doing here - it is hard to say - but there is certainly something beginning here. In any case, this poor girl of Izumo who died at one of the most picturesque places in Yamato… now I’ll think of her when I see the mist at Yoshino, for sure…

I may need to take a break from banka for my next post… too much death, too much pathos…

Been a little slow this week - but I’m gonna just keep going with my Vol 3 banka… This photo is quite old now (taken almost 10 years ago on Mt Lafayette in NH), but I still remember this hike vividly because I remembered how close the clouds seemed, and how they seemed to me to be rising out of, rather than hovering above, the mountains - and so naturally, this is the image that was called to mind by the following poem.

土形娘子火葬泊瀬山時柿本朝臣人麻呂作歌一首

One verse, composed by Kakinomoto no Hitomaro at the time of the cremation of Hijikata no wotome on Mt Hatsuse

隠口能 泊瀬山之 山際尓 伊佐夜歴雲者 妹鴨有牟

こもりくの初瀬の山の山の際にいさよふ雲は妹にかもあらむ

komoriku no/patuse no yama no/yama no ma ni/isayopu kumo pa/imo ni kamo aramu

Hidden away/is Mount Hatsuse – along the mountain ridge/those clouds that linger above: are they my beloved?

I apologize for the crazy syntax here (although I’m not really that apologetic), but the order of things is important here, as it is in most Japanese poetry (saving the verb to the end can make for some great twist endings!). It begins with a makura kotoba “komoriku no” meaning something along of the lines of “in an opening in a hidden spot,” i.e. hidden away, usually inferred to be among mountains - it does not only modify Hatsuse, but rather is used to set the stage for a number of place names that are fairly remote, hard to access, hidden among mountains and away from civilization/the capital. It thus serves a crucial function to set us in a particular remote locale, one that is literally “hidden away” from the rest of the world - a spot where the rituals of death and mourning can take place away from where they might pose the risk of pollution. After the introduction of Buddhism, and particularly following the cremation of Empress Jitō, who was the first royal to do so, cremation became increasingly popular as a funerary practice, and thus the mourning process was fundamentally altered – banka indeed at this point were a dying breed, being replaced by Buddhist ritual chanting appropriate to a Buddhist cremation rite. However, as we can see here, old practices didn’t just immediately give complete way to new: cremation was still taking place on mountains, far from settlement sites, where burial would have also primarily taken place (at least for the elite, whose tombs were usually positioned in some such remote locale, where the procession to the tomb site was also part of the ritual), and this would continue to generally be the case throughout the Heian period and beyond (even when done closer to the capital, the cremation was usually performed at a temple in the hills around the capital, rather than anywhere within the capital proper). Further, banka continued to be composed as part of the mourning ritual, at least through the end of the seventh and the beginning of the eighth centuries: it was perhaps re-styled as a way to process one’s feelings, as much as a ritual verse to placate the spirit itself, but the practice nevertheless persisted. And, indeed, as we can see here, cremation itself became a theme of such verses, perhaps because it was so new, and it figures more prominently into banka for such funerals than the actual burial process ever had (although there are definitely verses where the speaker proclaims his beloved to now be the mountain itself, or speaks of the tomb in some other way). In fact, here there is a touch of “elegant confusion” that seems to aestheticize the funeral pyre itself: the speaker cannot distinguish between the clouds rising above the mountain and the smoke from the pyre.

This is a striking image, perhaps even moreso because the smoke from the pyre becomes such a prominent metaphor for the impermanence of human life in later literature; here, the clouds linger (”isayopu”), almost as if they are unable to continue on, almost as if they are reluctant to leave the site. We are presented, in the first four ku, with a long modifier, all leading up to “kumo” (clouds), and thus ultimately a single image - clouds that linger, waveringly, along the mountain ridge of Mt Hatsuse. It is only in the final ku that we are aware the speaker sees these as something other than clouds, but rather, as “imo” (beloved, referring to the “wotome”/maiden from the preface, who is probably not Hitomaro’s lover but rather just some maiden whose death he was of aware of/whose funeral he attended and was asked to compose a verse for, and thus he channeled the voice of someone who would have loved her as an “imo”). The ending is in fact a rhetorical question, wondering if the clouds could in fact be her, but the implied answer is positive–that they are. Note that they are not likened to the smoke from the pyre, but rather to her herself. She is the smoke, and she is the clouds, there is no distinction - this is strikingly reminiscent of earlier banka that saw the deceased as the tomb, making no real distinction between them (being with the tomb=being with the deceased; here, seeing smoke=seeing the deceased, not merely a sign of them, but actually them). It is possible to see this lack of distinction between sign and signifier as part of a more ritualistic consciousness present in this verse, and this is, of course, a valid interpretation; here, however, I tend to think there is a nascent awareness of the poetic value of blurring the lines between two different phenomena, all while clinging to a ritualistic worldview. In other words, there is not necessarily a need to posit a binary between ritual verse/aestheticized verse, but rather, creating the confusion, and aestheticizing the smoke of the pyre by transforming it into gently lingering clouds along the mountain ridge is a new way to integrate banka into the funerary rite, yielding the bulk of the placation of the spirit to Buddhist chants, but also creating a space where the deceased could be posited as part of the landscape (since there was no longer a permanent physical marker of their presence such a tomb), and thereby for their permanent absence to be denied/negated, a natural and important part of the mourning process for the living. Banka seemed to have filled this niche only for a short time longer, however, for the deceased’s own writings came to have a similar significance of a persistent presence even after their death, and banka mostly fell out of common practice after the age of MYS. However, in this particular moment, they were a way to bridge the gap between the old and new funerary rites, and maintain a way forward for the living to grieve even in the absence of any physical reminder of their loved one.

It couldn’t have been easy to get used to the idea of cremation - and I think this poem shows us part of that process. There is no tomb to posit as the deceased maiden, so the clouds substitute for the smoke from her pyre - in that way, she continues to exist, and exist in a beautiful way. This was probably a comforting notion for those still bewildered by the change. In a way, it is not unlike how people handle the concept of cremation today - often they will spread the ashes of their loved ones at some spot, making them a part of the landscape, and in that way continue to feel their presence. It is a way to simultaneously acknowledge and negate the permanence of their death. Beautifully.

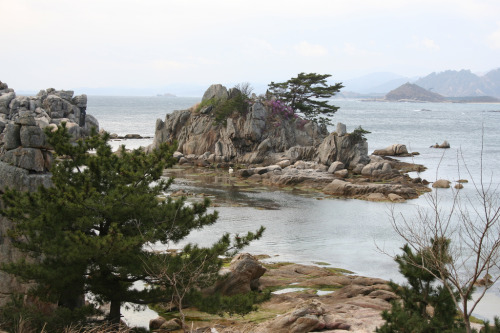

Photo from Sǒngsan Sansǒng (Fortress Mountain Mountain Fortress - one of my favorite place names ever) in Haman, Kyǒngsangnam-do, South Korea

I am loving me some banka from MYS vol 3, so I am probably going to keep going through them for the foreseeable future. I think I have yet another side project in the works on “drowned maidens” as a trope in MYS and the late seventh/early eighth century aesthetic worldview, but I’ll maybe talk about that ore in a few more poems when it begins to come up (because elegies for such maidens were a popular poetic topic, particularly when you passed by one of their graves - and there’s a bunch of them in vol 3, as elsewhere in MYS). For now, this poem is fairly straightforward, but also betrays a desire for some sort of contact with people beyond death that is not so common in banka (there’s usually more of a resignation to the fact that such contact is impossible, and a focus on the tragedy of such impossibility). It also gives us a glimpse into the ritual world of the late seventh/early eighth century, as far as it connected with the landscape and travel (i.e., movement across said landscape).

田口廣麻呂死之時刑部垂麻呂作歌一首

At the time of Taguchi no HIromaro’s death, one verse composed by Osakabe no Tarimaro

百不足 八十隅坂尓 手向為者 過去人尓 盖相牟鴨

百足らず八十隈坂に手向けせば過ぎにし人にけだし逢はむかも

momo tarazu/yasokumasaka ni/tamuke seba/suginisi pito ni/kedasi apamu kamo

Not quite a hundred/on this Eighty-cornered Hill/were I to present an offering/might I be able to encounter/one who has passed on?

The euphemistic language “suginisi” for something akin to “passed on” to another realm, means that on the surface this does not necessarily need to be a poem about death, and death does not need to be spoken of directly - important, as I mentioned in my last post, in a world where death=pollution; given that words and the phenomena they signify were considered to be closely intertwined and the power of words evoked through incantation (poetry), this was likely a real concern. Banka (elegiac verse) do very rarely speak of death directly. Rather, the transition from the world of the living to that of the dead–the crossing of that border, so to speak–is aestheticized through the likening it to transitional spaces such as “journey” (see previous post), or here, a mountain. Mountains were considered the gateway to the land of the dead, as it was there that the dead were often buried. Not only that, however, but mountains connected the phenomenal world with that of the spirits/supernatural, which we see also come into play here. Mountains were always ritual sites; when on a journey, an offering needed to be presented on each mountain to show respect to the gods who occupied it/were it (really, both). Failing to do so could have disastrous consequences - see the Kojiki version of the Yamato Takeru no Mikoto tale. So here, up until the third ku, everything is straightforward–”tamuke” is what is expected on the top of the mountain (here, “saka” is “hill,” perhaps, but the ritual significance is the same). However, the place is not simply where Hiromaro is buried (although it may well be, thus inspiring the verse); its name “eighty-cornered hill” is important here. “Not quite a hundred” (momo tarazu) is a makura kotoba that leads into “yaso” (”eighty”) that makes up the first part of the place name Yasokumasaka “Eighty-Cornered Hill.” It is really just a set up/lead in (”dōshi” in Konishi Jin’ichi’s terminology) to “Yaso” since “yaso” is literally “eighty,” but in common parlance was really used just to mean “a lot.” So “Yasokumasaka” is really a “saka” (”hill”) with a lot of “kuma” (corners, turns, but could also mean dark/shady spots - spots where no light touches - the nuance of which could come into play with the idea that it is here that one might meet the spirits of the departed). In any event, there are a lot of twists, a lot of corners, a lot of dark spots on this particular hill, and so all the more opportunity/possibility that this might be a spot where the dead are passing by - or are stopping to rest, etc. I do sort of picture it more as there being a lot of intersecting paths, which I think makes sense for the top of a hill, and so this is an appropriate “meeting spot.” In any event, this intersection of all the “kuma,” in the poet’s formulation, is a place that might yield a “meeting” with a departed person, if one presents an “offering.” The editors of NKBZ propose this particular term “Yasokumazaka” might have actually referred to a mythical place thought to exist between the land of the living and the dead, but this is simple speculation - although certainly possible that this was such a designation, I think the idea here is that we are on a mountain, which is already such an “in-between space,” and the “limitless” corners/paths that intersect at this place present the possibility that spirits could be encountered as they passed through (”sugi” also, of course, in non-euphemistic context, meaning “to pass through”). The “kedasi” (”might”) of the fifth ku is also significant in this regard, because although it implies perhaps more “probability” than “possibility,” nevertheless betrays a certain uncertainty, as does the conditional “seba” of “tamuke seba” (”tamuke sureba” would be more of a definitive). Thus this place is a barrier between worlds, an “in-between space,” but the ability to cross that barrier/create a link between those two worlds is conditional, only possible and not assured.

On the surface, this seems to just be describing ritual procedure/belief, and one does not really get a sense of Tarimaro’s grief over Hiromaro’s passing that we get from Hitomaro’s poem about the anonymous corpse (3:426, previous post). We can surmise from the poem that contact with a departed “spirit” was possible at such a transitional place while it was still “transitioning” to the other world - and this is consistent with what we otherwise know of funerary practices at the time (or rather, shortly before this time, perhaps), particularly the “mogari no miya,” where the body of the deceased was placed for an indefinite period (depending on status of the deceased) before being buried, so that the spirit might choose to return to it. Only after the spirit was thought to have transitioned to the land of the dead was the body finally interred, and later, cremated. Thus as the spirit made its way from the body to the land of the dead, it may have been possible to make contact with it, if one followed proper procedure. Elsewhere in banka it is rare to see a desire or an admission of possibility of contact with the deceased, as noted above - and here, I think it only works because the death is recent, and the spirit was thought not to have fully crossed the “barrier” yet. Not until the rise of Pure Land Buddhism among the aristocracy in the Heian period do we really begin to see a belief in the ability to “meet again” after death among people - it is not something that appears to have been prevalent in MYS times/before. Rather, here I think the “meeting” of the departed has more to do with the waiting period for/attempt to call the spirit back to the body. Making contact could with the spirit at “Yasokumasaka” could help remind it to return to the land of the living, before it crossed into the world of the dead.

Tarimaro’s expression of grief is thus less overtly emotional, but is no less desperate, no less heart-wrenching - his reaction to the death of Hiromaro is not to mourn/grieve, but to deny its finality. This is of course, another very human way to handle such a tragedy, and something I’m sure a reader in any time can relate to. If only he could present an offering on Yasokumasaka, he might meet his dearly departed friend, and call him back to life. Then there would be no reason to grieve, no reason to mourn. This is a very different sort of banka - one I have yet to see elsewhere. Banka are usually all about the grieving process - and they may have a degree of denial - accusing the dead “how could you” and the like - but they rarely propose to do something about it. Of course, in the fifth ku’s “kedasi” there is the glimmer of realistic expectation that such a meeting may be beyond the possible, but on the whole it conveys an optimistic tone. It is not lamenting the impossibility by implying the possibility; “kedasi” indicates the speaker really believes he could meet Hiromaro’s departed spirit. Thus as readers/listeners to his verse we are keenly aware of the tragedy of his state of mind that denies the finality of death, and yet he is not - the pathos is not intrinsic to the verse in this case, but emerges in the reading process.

My favorite part about reading MYS verse, as I have said before, is how potently I feel the emotions of the poets all these centuries later, and I think this particularly true with banka. Although the grief, the desperation of the speaker’s voice is often what moves me with these, here I can’t help but pity Tarimaro and his lack of acceptance. He can’t “move on,” so to speak, thinking that Hiromaro’s spirit has yet to “move on,” and so he takes comfort in the possibility of ritual to bridge the gap and avert the finality of death. Such ritual practice was probably already dated in his day, having been replaced by Buddhist funerary rites, and yet there is solace, there is comfort to be found in old traditions. Generations of ancestors believed in such things, and if one is desperate enough, unwilling to accept enough, then such rituals are perhaps the only relief. That too, again, is very relatable, even to me, 1300 years later..

Of course I don’t have a photo of “Yasokumasaka,” given that we don’t know if it is a real place/where it might have been, but I offer up this photo taken this summer on an ancient mountain fortress in Haman, southern Kyǒngsang province, South Korea, because there was this odd rock arrangement in a clearing - that really could be anything, but I imagined it was a ritual space, each stone serving as an altar for the spirits of the mountain and the surrounding landscape. It may not be the special “intersection” that Yasokumasaka was, but as with any mountain (and this one is actually more of a “saka”), is an “in-between” space, where one might just meet a spirit wandering, searching for the gateway to the world of the dead.

So, continuing on in Vol. 3 of MYS, immediately following the chōka + hanka of my last post, there’s this Hitomaro poem… that is just… wow. The pathos, the immediacy of it–there’s nothing I love more than a poem that speaks across the centuries in profound ways like this one does. Of course I’m not gonna use a photo of a corpse… but I thought one of these ground-level shots from my Yongmunsan trip went will with the image here of a body, simply collapsed on the mountain path. Perhaps it’s almost the perspective of the corpse?

MYS 3:426

柿本朝臣人麻呂見香具山屍悲慟作歌一首

One verse composed by Kakinomoto no Asomi Hitomaro, as he grieved deeply upon seeing a corpse on Kaguyama

草枕 羈宿尓 誰嬬可 國忘有 家待<真>國

草枕旅の宿りに誰が嬬か国忘れたる家待たまくに

kusamakura/tabi no yadori ni/ta ga tuma ka/kuni wasuretaru/ipe matamaku ni

Grass for a pillow/stopped for lodging on his journey/whose spouse might he be?/he has forgotten his home/while his household surely awaits his return…

The first thing that strikes me here is that the kotobagaki (preface) is absolutely essential to an understanding of the poem… knowing that Hitomaro is reciting this upon seeing a corpse makes the impact here considerably more profound - he is not composing on a fellow traveler, himself, or even a stag or the like… and so when he speaks of “having forgotten his home” [”kuni wasuretaru”] and “household surely awaits him” [”ipe matamaku”], we know there is an implicit negation of the possibility of that waiting being fulfilled, that forgetting being reversed. As a fellow traveler, Hitomaro cannot help but be drawn in to sympathize - after all, journeys were truly dangerous then, and there was real possibility of death (although, to be honest, Kaguyama is right near the capital so it’s a bit of an exaggeration to think of it as a true “journey,” but Hitomaro nevertheless evokes the word “tabi,” leading into it with the makura kotoba/epithet “kusamakura” grass for a pillow; in any case, dying away from home was probably more or less considered the equivalent of dying on a journey - and the move to create a connection between himself and the corpse necessitates an appeal to the idea of “journey” as that is what they have in common - both are/were travelers along the mountain path - and in any event, the poem here thrives on the contrast between “journey” and “home” and their incongruence). Hitomaro, seeing the corpse lying in the mountains, immediately equates him with a traveler having stopped for the night, but one that can never return home - because he has forgotten his “home” (’kuni’ is essentially referring to his home village) in laying to rest here. He cannot return, and yet Hitomaro imagines those at home awaiting him in vain - and he cannot help but see the utmost tragedy and pathos in not only his having died here, alone, unable to make it home, but the lack of knowledge of that reality of the people at home, who can only continue to wait. Moreso than the corpse himself, the “ipe” [household] is cast as pitiable here, as the “mu” suffix (plus +ku to nominalize) creates the sense of speculation on Hitomaro’s behalf but also indefinite continuation, from the present into the future. This man - he must be someone’s husband [”ta ga tuma”], Hitomaro reasons, and it is that someone who is to be pitied in this situation, for she shall remain unaware of his fate, forever waiting for his return - he, having forgotten her as he laid to rest away from home.

Now, detractors like Ebersole would be sure to note here that there is more going on that Hitomaro simply empathizing with the plight of the anonymous corpse’s wife, and he would be right. There is certainly and necessarily a ritualistic aspect here - because corpses were considered polluting “kegare” - and were to be avoided at all costs - but death could simply not go unrecognized, either. And so it is perfectly reasonable to see Hitomaro’s poem as part of a ritual of placating the dead and the accompanying pollutant effect on the living of their presence - and also probably purifying the mountain, which was, after all, one of the three sacred mountains of the Asuka area/the Fujiwara capital. In other words, once noticed (見), the corpse needed to be dealt with in an appropriate manner, and this poem was probably part of that. However, the pathos infused in Hitomaro’s verse surely goes beyond mere ritual, in imagining him as not just a body but a person, who has left behind home and family in dying far away form them. This act of personifying the corpse and imagining those left behind is an astonishingly human reaction to death, one that even betrays a bit of self-insertion on the poet’s behalf, and goes above and beyond what was probably necessary for the purification of the precincts where he died. Hitomaro felt general emotion for this poor fellow, unable to make it home to die. How lonely for both he and his family - what a pathetic fate, one so illustrative of the cruel ways of the world. There may be no Buddhist message about the impermanence of human existence here yet, but there is a comparable almost existentialist subtext - where life and death alike are clearly “unfair” - having no inherent logic or reason to them. In any case, the emergence of a deep “pathos” in Japanese poetry, where the poet empathically reacts to sights and sounds of the world, can be seen here even in what may have been arguably a ritual context. Emotion and empathy are indeed also a part of ritual, but there is something about the pathos that echoes in Hitomaro’s voice here that seems fresh, even new in its moment, and moves a reader even 1300 years later to tears over this poor man’s wife who would never see her husband again, he having died by the wayside, alone, on a journey.

IMG_6586by Margi

I’m back - going to try to churn out at least a couple posts a week. I was in Korea for my research for the latter half of 2015… back stateside now, and hoping to start my days with a refreshing poem from MYS. I suppose this is not the most up-lifting poem(s) to start out with - but it spoke to me. Also, it’s a chōka/hanka combination, so there’s a lot of it, which somewhat? makes up for no posts for almost a year.

MYS 3:423-425

同石田王卒之時山前王哀傷作歌一首

As in the previous poems, upon the death of Ishida [Iwata] no Ōkimi, a poem composed by Yamasaki [Yamakuma] no Ōkimi as he grieved

角障經 石村之道乎 朝不離 将歸人乃 念乍 通計萬<口>波 霍公鳥 鳴五月者 菖蒲 花橘乎 玉尓貫 [一云 貫交] 蘰尓将為登 九月能 四具礼能時者 黄葉乎 折挿頭跡 延葛乃 弥遠永 [一云 田葛根乃 弥遠長尓] 萬世尓 不絶等念而 [一云 大舟之 念憑而] 将通 君乎婆明日従 [一云 君乎従明日<者>] 外尓可聞見牟

つのさはふ 磐余の道を 朝さらず 行きけむ人の 思ひつつ 通ひけまくは 霍公鳥 鳴く五月には あやめぐさ 花橘を 玉に貫き [一云 貫き交へ] かづらにせむと 九月の しぐれの時は 黄葉を 折りかざさむと 延ふ葛の いや遠長く [一云 葛の根の いや遠長に] 万代に 絶えじと思ひて [一云 大船の 思ひたのみて] 通ひけむ 君をば明日ゆ [一云 君を明日ゆは] 外にかも見む

tunosapapu/ipare no miti wo/asa sarazu/yukikemu pito no/omopitutu/kayopikemaku pa/pototogisu/naku satuki ni pa/ayamegusa/pana tatibana wo/tama ni nuki[nukimazipe]/kadura ni semu to/nagatuki no/sigure no toki pa/momitiba wo/worikazasamu to/papu kuzu no/iya toponagaku[kuzu no ne no iya toponaga ni]/yoroduyo ni/taezi to omopite[opobune no omopitanomite]/kayopikemu/kimi wo ba asu yu[kimi wo asu yu pa]/yoso ni kamo mimu

Horns creeping up/along the road to Iware [Craggy Land]/each morning, without fail/he had traveled/lost in his thoughts/as he went– In the fifth month, when the cuckoos cry out/the wild irises/and the flowering oranges/making them into beads on a string [stringing them both up]/shall I make a crown?/In the ninth month/at the time of early winter’s rains/the yellow and crimson leaves/shall I break them off to adorn my head?/Like winding kuzu vines/that stretch ever far and long [like the roots of the kuzu vines, stretching ever farther and longer]/for the myriad ages/this would not come to an end, he thought [like a great ship, he relied upon this belief]/as he traveled back and forth–As for my lord, from tomorrow [My Lord, from tomorrow]/will he be looking upon it from afar?

或本反歌二首

Two echo verses found in one text

隠口乃 泊瀬越女我 手二纒在 玉者乱而 有不言八方

komoriku no/patuse wotome ga/te ni makeru/tama pa midarete/ari to ipazu yamo

Surrounded by mountains/the maiden of Hatsuse/those beads she had wrapped about here wrist/have now scattered about/you might say…

河風 寒長谷乎 歎乍 公之阿流久尓 似人母逢耶

川風の寒き泊瀬を嘆きつつ君が歩くに似る人も逢へや

kapakaze no/samuki hatuse wo/nagekitutu/kimi ga aruku ni/niru pito mo ape ya

The river winds/are chilling in Hatsuse/sighing, sighing/as you walked along/will I ever meet another like you?

右二首者或云紀皇女薨後山前<王>代石田王作之也

As for the above two verses, in one text it says these were composed by Yamasaki no Ōkimi on behalf of Ishida no Ōkimi after Ki no hime miko passed away.

The main long verse hinges on the location of a road through Iware which connects Hatsuse and likely the Fujiwara capital, via which the subject of grief, Ishida[Iwata] no Ōkimi “commuted” [kayopikemu] (Scholars speculate the “Hatuse maiden” in the first hanka could be his wife, living out in the country, to whose home he commutes back and forth, from his post in the capital, along the Iware road). Interestingly, the poet is attempting to imagine the thoughts of Ishida as he traveled back and forth along the road–well particularly as he traveled up to the capital each morning–and they can’t get much more elegant (fūryū 風流) - Ishida was a man of true taste, it seems, or that’s how Yamasaki wants to present him, in any case. As he encounters irises and orange blossoms in the summer (fifth month=second month of summer by lunar calendar), he appreciates their beauty and his thoughts turn to fashioning them into a flower crown for his head; as he encounters autumn foliage, he again thinks the same thing. Recognizing the beauty of these things and seeking to adorn himself with it is perfectly fitting for a late-seventh century aesthetic - where you couldn’t get much more elegant (cf. Princess Nukata on spring/autumn, or any number of poems from this period about wanting to “kazasu”(adorn) oneself with something). There are quite a few makura kotoba here, which contribute interesting “stage-setting” that enables the poet to move through space, like Ishida is moving along the road: first, the scene of Iware is set by leading us into the word “Iwa” (boulder) via the epithet “horns creeping up”–thus we get an image of craggy, rocky cliffs, rising up into the sky–a mountain pass. Then comes the figure moving along the road each morning, and w are zoomed into his location, and finally his mind, and we see what he sees. The next makura kotoba comes following the two “thoughts” of Ishida (each ending with “to”), where a great length of time is translated into an image of ever stretching, ever inching forward kuzu vines. It is here where we get the sense of a sudden, unexpected death–or rather, one for which Ishida himself was unprepared. He had thought such journeys of his would continue indefinitely, stretching forward into the future far and long like kuzu vines, but such was not to be the case. There is no awareness of the ephemerality of life–just expectation that things will continue as they are indefinitely, until, of course, they don’t. That seems to be the real tragedy here–Ishida, a man of elegance, appreciated each aspect of his daily journey, but he didn’t appreciate that such journeys were limited, that they couldn’t go on forever. And so in the end, he who had traveled the road daily and knew it so well, can only look upon it from afar [yoso ni kamo mimu]. That’s a very powerful way to end the verse–he is no longer a part of the scenery, it goes on without him, and he is now only a distant observer (perhaps looking upon it from the underworld, which coincidentally, was located in the mountains). He didn’t expect, no one expected, for him to so abruptly vanish from the scene, but he was the one aspect of it that could not be renewed, could not be repeated. This is less a traditional banka, expressing grief over the loss of a loved one or a public figure, and more of a personal lament, that focuses on someone who was lost, but in doing so conveys a deep truth about human experience, and expands beyond the purview of a mere song of grief. Perhaps there is subtext here about impermanence, although perhaps not in a fully Buddhist sense, in the way the verse highlights the un-awareness of Ishida of the relatively fleeting nature of his existence, and the fact that it could not go on forever. Granted, the “yoroduyo ni taezi” type locution is common in banka which lament the fact that, particularly for rulers, no one thought they could die, everyone thought they would live and rule forever (well, not literally, but it’s a thing you say when a ruler dies), but here it’s not the cries of grieving loved ones who can’t believe the deceased is gone, but it’s actually a speculative thought of the deceased himself while he was alive (”yoroduyo ni taezi to omopite”) - he was the one who thought he’d be around forever. And now, of course, he is on the “outside” (”yoso”). Yamasaki doesn’t focus on his own grief. Rather, he enters Ishida’s head, to present an elegant, innocent man who can no longer travel the scenic road of which he had so been a part in life, and who in some way laments that fact in the end “from afar” (yoso). There are elements of Yamasaki’s voice that bring us out and remind us he is speculating, projecting for us what Ishida must have been thinking - but the overall effect is that we are more aware of the tragedy of Ishida’s unawareness of impermanence and his abrupt disappearance from the scene than we are of Yamasaki’s own grief over the loss of Ishida. Of course, Yamasaki is bereaved, but we also get the sense that Ishida’s passing has inspired an acute awareness in him of the speed at which the everyday can become precious, and even when each moment of the mundane is savored in a most elegant way–it can all end just like that, leaving one forever “on the outside.”

The hanka obviously inspire confusion, since there is a footnote suggesting they perhaps don’t even belong to this chōka but instead were written on a different occasion, grieving a different death. So people didn’t even know in the eighth century, how can we? Well, the footnote may be right, but I think the imagery and themes present in the hanka match the chōka pretty well, even if they were not composed together (but I kinda think they were). First, “komoriku no” has an echo of “tuno sapapu” from the chōka, and although Hatsuse is not mentioned in the chōka, geographically it can make sense that was where Ishida was coming from along the Iware road. The maiden is again, not mentioned in the chōka, but I think suddenly shifting to not only giving us an explanation for the “commuting” but also to the grief of one left behind, that is not in fact the poet himself, is fitting for a hanka. “Jewels/beads” (tama) wrapped around her wrist echoes the “tama ni nuki” of the chōka, and is a striking image for death - that the man she had kept “wrapped around her wrist” is now gone, scattered like beads from a string. The other obvious connection, is of course, that “tama” (bead) is cognate with “tama” (spirit), i.e. his spirit has left her, scattered away. The ending is a little strange, “might one say?/you might say..” is a little ambivalent, but perhaps is used to fill out the syllables, and further has an emphatic, grieving tone with the “yamo” at the end. One can feel almost a desperation in the ambivalent tone as well, as if the poet, and perhaps also the maiden, are struggling to find the words to describe what has happened, the describe what they are feeling. The second hanka is a bit more straightforward, a lament that one will never see the likes of Ishida walking along the road again. Everything in the entire verse modifies “pito” (person) in the final ku, which is again fitting - because it emphasizes there will never be another ‘person’ like him (”niru”). Hatsuse appears again here, this time as place of cold “river winds,” which accords another layer to the figure traveling back and forth along the road. Further, the “nagekitutu” suggests a feeling Ishida, one consumed with love for Hatsuse no otome, perhaps, but also moved by the nature around him, which echoes the content of the chōka, but from a distance, rather than from inside Ishida’s head.

Together I found these verses a tour de force - there’s no heavy-handed lamenting of impermanence here, no desperate shouting about how he wasn’t supposed to have gone, how can he have left the world behind, etc. Rather, this is a different sort of tribute, one I think you see emerging in the late seventh and early eighth centuries and definitely in Hitomaro’s work, where the deceased is the focus, rather than those left behind, necessarily, although there is of course both here. By speculating on Ishida’s mindset, Yamasaki is of course both avoiding talking about his own grief and conveying the sense of the second hanka, i.e. that he will never meet another like him, but this is done in a subtle way that is both appealing and refreshing when compared to earlier more ritualistic literal “coffin-pulling” poems (banka). There is in any event a lot of striking imagery, use of makura kotoba, and deep sentiments here.

Feels good to be reading MYS again. I was interested in maybe talking a little bit about the little “one text says” parts of this verse, because I think they are remarkably informative and striking “alternatives,” but for now I think I’ve gone on long enough about these verses.

The photo is from when I climbed Yongmunsan in Kyǒnggido back in October during the height of the foliage. I figured, mountain road, crimson leaves, it sort of works. One thing I do miss about being in Korea – mountain climbing on demand, any time, any where.

I searched my entire collection for a good photo for these. There was nothing quite right, but this will have to do.

有間皇子自傷結松枝歌二首

Arima no Miko, two verses composed bemoaning his own fate as he tied together two branches of pine

磐白乃 濱松之枝乎 引結 真幸有者 亦還見武

磐白の浜松が枝を引き結びま幸くあらばまた帰り見む

ipasiro no/pamamatu ga e wo/pikimusubi/masakiku araba/mata kaperi mimu

In Iwashiro - I tied two boughs of the shore pines; if I am truly fortunate, I will return to look upon them once more.

(MYS 2-141)

家有者 笥尓盛飯乎 草枕 旅尓之有者 椎之葉尓盛

家にあれば笥に盛る飯を草枕旅にしあれば椎の葉に盛る

ipe ni areba/ke ni moru ipi wo/kusamakura/tabi ni si areba/sipi no pa ni moru

When at home, I pile my rice in a bowl; since I am on a journey, I pile it atop leaves of chinquapin.

(MYS 2-142)

長忌寸意吉麻呂見結松哀咽歌二首

Naga no Imiki Okimaro, two verses composed in despair upon seeing the “tied pines”

磐代乃 <崖>之松枝 将結 人者反而 復将見鴨

磐代の岸の松が枝結びけむ人は帰りてまた見けむかも

ipasiro no/kisi no matu ga e/musubikemu/pito pa kaperite/mata mikemu kamo

That person who is said to have tied together the shore pines at Iwashiro - did he ever return to look upon them once more?

(MYS 2-143)

磐代之 野中尓立有 結松 情毛不解 古所念[未詳]

磐代の野中に立てる結び松心も解けずいにしへ思ほゆ[未詳]

ipasiro no/nonaka ni tateru/musubi matu/kokoro mo tokezu/inisipe omopoyu

The “tied pines” that stand in the field at Iwashiro - like them, my heart does not unknot as a time long ago comes to mind. (author unclear)

(MYS 2-144)

山上臣憶良追和歌一首

Yamanoue no Okura, one verse composed as a follow-up

鳥翔成 有我欲比管 見良目杼母 人社不知 松者知良武

鳥翔成あり通ひつつ見らめども人こそ知らね松は知るらむ

tubasa nasu/arikayopitutu/miramedomo/pito koso sirane/matu pa siruramu

Having become winged, you surely continue to look upon them as you fly about the sky; people may not know this, but the pines surely do.

(MYS 2-145)

大寶元年辛丑幸于紀伊國時<見>結松歌一首 [柿本朝臣人麻呂歌集中出也]

In the first year of Taihō (younger brother of metal, ox), on the occassion royal outing to the land of Ki, one verse composed upon seeing the “tied pines” (This appears in the Kakinomoto no Asomi Hitomaro collection)

後将見跡 君之結有 磐代乃 子松之宇礼乎 又将見香聞

後見むと君が結べる磐代の小松がうれをまた見けむかも

noti mimu to/kimi ga musuberu/ipasiro

Thinking he might look upon them again, my lord tied these together: the small pines of Iwashiro, did he ever again look upon their boughs?

(MYS 2-146)

These six verses kick off the “banka” (elegy; or “coffin-pulling” verse) section of the second book of Man’yōshū, although the compiler admits they are not very banka-like in a note that follows Okura’s poem:

右件歌等雖不挽柩之時所作<准>擬歌意 故以載于挽歌類焉

The poems to the right were not composed on the occassion of “pulling the coffin”; however, the content of these verses matches up, and so for that reason they have been put into the category of “banka.”

This suggests that the category of “banka” was still relatively new and fluid: the first two of these verses are supposed to be by Arima himself! How could he have possibly composed his own elegy? The verses by Okimaro and Okura that follow seem to fit the category of “banka” a bit better, as they lament Arima’s unfortunate fate, but were likely composed on the outing to Ki in 701 mentioned in the headnote to the final verse, and thus some forty years after Arima’s demise. The section places all these verses under the reign of Saimei, but again that only works in terms of “content.” However, the story of Arima’s “tied pines” seems to have been a famous tragedy at this point, and so having a section on it in the volume is fitting, and perhaps “banka” was chosen to tell this story, for lack of a better available categorization.

Prince Arima was the son of the sovereign Kōtoku, brother of Saimei and both her successor (as Kōgyoku) and predecessor (as Saimei). He lived just eighteen years, executed for having become involved in a plot to manipulate succession in his favor, egged on by Soga no Akae, the grandson of Soga no Umako (who was killed by Tenji, then Prince Naka no Ōe). Akae later betrayed him to Naka no Ōe, leading to the prince’s capture in the province of Ki. He pleaded that he had no knowledge of a plot, and such was all Akae’s doing; he thought he might be safe, but alas, he was executed in Ki soon thereafter. The first two poems are supposedly from the brief period between the time of his capture and his execution, and are thus imbued with a deep sense of pathos as the prince is aware he will likely never see the “tied pines” again.

The first poem describes the act of tying the pines together at Iwashiro, which becomes a symbol of the prince’s tragic fate for the following poems. It has the structure of a ritual-prayer verse, as it seems to be imploring the pines to allow him to return and look upon them by ensuring his safety. This is a typical prayer-structure: describing the act of the prayer, then its content; however, the content is never relayed as a direct address, but states the desired outcome in either present or future. The act of tying the pines together also undoubtedly has ritual significance, and so there can be no doubt that this verse was meant to evoke the sympathies of the local deities to ensure his safety. (ma-sakiku, which I have translated above as “truly fortunate,” really implies fortunate in the sense of safe/without harm). If we read this as having been composed in the mid-seventh century (some scholars argue the poems were later attributed/proxy-composed for Arima), then the ritualistic understanding is most appropriate. However, by the time of Okimaro and Okura, Arima’s poem is re-interpreted as being imbued with pathos, with Arima’s awareness of his impending execution and his desire to leave a physical katami (memento) of his presence on the landscape, a landscape which he will never see again. The ritual meaning may not have been entirely lost, but had likely been caught up in the lore of the prince’s tragic death, such that it was now more about that lingering symbol of him, while he himself was long gone from the earth, than it was about his final plea for divine mercy.

The second verse attributed to Arima at first glance seems considerably less powerful and that it almost doesn’t fit here with the other five, but actually carries over many similar sentiments from the previous. It is perhaps, in contrast with the previous, a lyric expression of the prince’s awareness of his inability to return to his former life, and his impending end, in contrast to the plea in the previous verse (one might also argue, however, that the act of making such a plea is an expression of his awareness of the inevitability of his death). He had been accustomed to a life of rice in a bowl - a proper container - but now he has been cast out of his former position, his former life, and finds himself eating rice atop “chinquapin” (a type of beech tree) leaves. He says this is “because [he is] on a journey,” but in the context we know this is no mere “journey,” but something with considerable more finality–there is no possibility of return. We are thus afforded an image of a prince partaking of his final meal, out on the frontier, away from everything he once knew. We sense harsh winds blowing in from the ocean, through the pines which he tied together, as he awaits the inevitable. HIs last meal in this rustic, harsh setting is atop beech leaves. Is he still a prince in this poem? Perhaps, but one who has surely lost everything at this point.

Arima’s two verses are thus interesting “banka” in that they look forward to death with despair and resignation (with perhaps a dash of hope in the plea, but again it may be ironic), rather than look back from death in anguish and lament. The perspective of the one “who will die” is undoubtedly unique. I can’t think of any other examples quite like this. It is the awareness of the impending end, and its inevitability, that plays further into the pathos of remembering Arima in Okimaro and Okura’s poems. Arima’s poems offer his respondents of a later age a glimpse into his mind as he looked forward to death, connected with a concrete image of the “tied pines,” to which they too, presumably have access when visiting the shores of Ki, which then prompts them to remember and compose. They know the pines were tied together as a ritual act, perhaps, but also as one that would symbolize hope against hope that he might see them again: it is the fact that this hope was dashed that is so incredibly aware (pathos), and which becomes the focus of Okimaro and Okura’s verses.

The first Okimaro poem does little more than rephrase Arima’s first verse in the third person, but as a response to Arima’s verse from someone aware of the outcome, it is strikingly powerful. Okimaro asks if that person who tied together the pines ever did return, and it is the implicit knowledge that he did not that moves one to the verge of tears. The second poem (which, for some reason, is followed by a note that the author is unknown, despite it being attributed to Okimaro in the headnote…) is more about the speaker, in his moment, reflecting on the past as he sees the pines still tied together in the present. Like the knotted pines, his heart is “knotted” as he remembers Arima’s tragic fate. The second poem is thus more explicitly a lyric response to the sight of the “tied pines” and their associated lore, by the poet himself in the present moment, while the first focuses more on the tragedy of the past.

Okura’s poem does something quite different: it attempts to find consolation in the idea that Arima’s spirit must have transformed into a bird (an old belief attested in Kojiki), and thus could fly about the sky and look upon the pines from there - and while the people of the world regard Arima’s inability to return to the pines and look upon them a tragedy, the pines themselves know Arima has in fact returned, as a spirit. Okura is indeed a unique poet, and this is an example of how his perspective at times utterly deviates from the standard: he is one of the few poets that I am aware of to seek comfort in the notion of an afterlife, a state beyond death that allows for the fulfillment of the otherwise tragically unfulfilled promises of life. Most banka, as with Okimaro’s, simply lament and bemoan that unfulfillment, recalling it in the present and being moved to tears, but rarely seeking any relief from that. This is indeed something I’d like to look more into…

The final poem I’ve included here, which rounds out the Arima section, is said to be taken from the Hitomaro kashū, but that does not necessarily mean it is by Hitomaro. It is in many ways similar to Okimaro’s first verse, in that it rephrases in the third person the first, more ritualistic of Arima’s verses. It does begin with “nochi,” however, which is a quite powerful word (when compared with kaeru “return,” I would argue), because we know there was no “nochi.” For Arima, there was only the now, there was never a “later,” and our knowledge of that, along with the poet’s of course, is what makes this poem a powerful response to seeing the pines in the present (from Arima’s perspective, “nochi”). Others see them “nochi” and recall Arima - but Arima himself never had such an opportunity to look upon them again.

Okura’s poem is really the stand out in the bunch. I really enjoy him. If I had the time, I would have a blog solely about him.

I have paired this with a photo from my trip to Kǔmgangsan, North Korea, in April 2006, mostly because it was one of the few photos in my collection that featured a pine on the shore, and I also enjoy the large boulders as evocative of the name “Iwashiro.” Unfortunately, none of the pines are “tied together” - I am now going to be on the look out for such things, however, and perhaps can provide a better photo at a later date. If you plug 結び松 into google images, however, you can get an idea of what it likely looked like.

Well, that might be enough aware for the day.

Post link

923 on Flickr.

山部宿祢赤人詠故太上大臣藤原家之山池歌一首

Yamabe no sukune Akahito, one verse composed on the garden pond at the mansion of the late Fujiwara Chancellor (Fuhito)

昔者之 舊堤者 年深 池之瀲尓 水草生家里

いにしへの古き堤は年深み池の渚に水草生ひにけり

inisipe no/puruki tutumi pa/tosi pukami/ike no nagisa ni/mikusa opinikeri

The weathered bank of the past–since it has been a great many years, now on the shore of the pond water grasses flourish!

(MYS 3-378)

I seem to have moved into Volume 3, quite unplanned, but fitting perhaps since the rest of volume 2 is banka (elegiac verse) and doesn’t really seem to go with the theme of the blog. Although, in its own way, this verse too is an elegy.

Probably a little more than a decade after the death of Fujiwara no Fuhito, one of the most powerful politicians of the early Nara age, Yamabe no Akahito, one of MYS’ “greats,” stands on the banks of a garden pond within the grounds of his former mansion. We don’t know if his descendants are still living there (and let’s face it, they probably were), but that doesn’t matter - the pond has fundamentally changed since the days when its former master looked after it. Ooh, I’m getting close to a political reading here, and I think it’s certainly possible - but I don’t really want to go there. I think what’s more important here is the lament of the passage of time, and the seeming indifference of natures’ cycles to the impermanence of human experience.

The poem begins by emphasizing the temporal distance between Fuhito’s age and the poem’s present by repeating “inishie” and “furuki” - two words that evoke the past, but “furuki” also implying erosion, wearing down, “becoming old.” The bank is the bank of the past, but it is now weathered down, a shadow of its former self. The next line tells us why this is the case: many years have passed. We implicity understand that these are years since Fuhito’s passing. The pond is the pond of old, and yet years separate its past from its present. Its continued existence evokes the past, but can never recall it - a barrier of “water grasses” has arisen around its edges to convey just such a reality. Thus the irreversibility of time, the irrecoverability of the past, that all-too-familiar poetic topos, is what emerges here, but to striking effect, and with considerable poetic technique. The poem relies on linguistic linkages that add another level to it: inishie and furuki mean similar things, but their different nuances serve to set up the parallel between past and present in an efficient, succinct manner; ‘tsutsumi’ (bank) is juxtaposed with 'nagisa’ (shore) below, the former being what once was and is now eroded (furuki), the latter being the new site of growth for the water grasses, whose new life stands in sharp contrast with that which once was, but at the same time evokes the cyclicity of nature (the law of rise and fall); the third ku, “toshi fukami,” literally translates “as the years are deep,” with “deep” very smoothly transitioning into the first word of the fourth ku, “pond” - thus years and water are explicitly likened to one another - both creating distance, the former temporally and the latter spatially. Thus this poem is much more than Akahito simply lamenting that Fuhito’s household has been slacking off on their gardening maintenance since his death. It wouldn’t matter if the pond looked exactly the same - and it certainly wouldn’t be poetic if it did. What is interesting is the way the scene maps onto the pathos associated with the irrecoverability of the past, of which Fuhito was apart. That is what makes it the “right” image through which Akahito might convey such emotive content, because it conjures spatially the types of temporal barriers felt by those “left behind”, while the landscape itself is also not unaffected by time, and through the conflation of the water grasses and the “deep years,” acquires an affect of its own, one of longing for a past that will always remain irrecoverable.

Ah, there’s a reason Akahito is “one of the greats.” I have paired this poem with this photo of a garden pond taken on the grounds of a museum in Yǒngju, North Kyǒngsang province in South Korea. I thought it captured the scene of a carefully constructed and formerly well-manicured garden pond, that has now seen “water grasses” growing up on its shores. I think that those have nice orange flowers and so were probably planted there, and you can see the grasses on the far banks are still kept short, so it’s not quite the level of “sabi” that perhaps Akahito is evoking, but the algae and lotus on the surface of the water cause it to almost blend into the green landscape in a way that does suggest something of the atmosphere of Akahito’s verse. And in any case, I was going through these old photos and found I really enjoyed this one.

Post link

IMG_1296 on Flickr.

式部卿藤原宇合卿被使改造難波堵之時作歌一首

Lord Fujiwara no Umakai of the Ministry Ceremonial, one verse composed on the occasion of the re-building of the Naniwa capital

昔者社 難波居中跡 所言奚米 今者京引 都備仁鷄里

昔こそ難波田舎と言はれけめ今は都引き都びにけり

mukasi koso/nanipa yinaka to/iparekeme/ima miyako piki/miyabinikeri

In the past, Naniwa may have been called a country outpost–but now, moving the capital here, it truly has the air of a capital!

(MYS 3-312)

The translation does not do this justice. It is truly a brilliant poem, and I had quite a few giggles when I first discovered how perfect it was for expressing my feelings upon visiting the Naniwa capital site located in modern day Osaka. Naniwa, briefly the capital in the mid-seventh century under Kōtoku, was kept up as a “detached”/secondary capital/palace located close to the sea from the age of Tenmu (r. 673-686) through that of Shōmu, Tenmu’s great-grandson (r.724-749), when it briefly became the full-on capital again for most of 744. It was ultimately dismantled for materials for the building of Kanmu (r.781-806)’s new capital at Nagaoka. Amidst all this, this poem’s poignancy could have been felt at various points, but is contextualized by MYS as coming from Fujiwara no Umakai, an official who was involved in the rebuilding efforts of the Naniwa “capital” (miyako/miya slippage is dificult to convey in English - this was a “capital” in the sense that there was a palace there for the ruler to reside in/“rule” from). He was appointed to such a role in 726, a full 18 years before the capital was ultimately moved to Naniwa. Thus, seeing Naniwa assuming an air of the cosmopolitan as a new capital would have been quite a personally moving experience for him. To see this distant outpost, an appointment to which would have amounted to effectively banishment for him (for any appointment away from the capital generally meant you had somehow fallen out of favor and no one wanted you around for the foreseeable future), now become the capital, would have been absolutely breathtaking. The collapsing of distance between center and periphery meant the collapsing of distance from Umakai to the center of power and culture, and that he was being welcomed back in. But this verse is striking because it can be understood as a narrative of the history of the Naniwa palace as a whole, which is why I bothered to outline it above. Naniwa, despite being a major port of entry for trade goods and foreign emissaries, was usually considered a distant country outpost, far from the cosmopolitan center that was the courtly capital. There were a few moments where it managed to rise to center stage (under Kōtoku and Shōmu), but these moments were always fleeting. But since the waning of the power of the aristocratic bureaucracy in the medieval period, and the gradual “capitalization” of the economy that occurred in the Early Modern Period (17th-19th centuries), modern day Osaka has been, for all intents and purposes, much more of a “capital” than Kyoto, or Nara, for that matter, had ever been. Of course this is an entirely different sense of capital - that of an economic center, rather than a political/courtly one, but reading the poem with a looser understanding of “capital” allows its import to carry through the ages, such that it is just as poignant uttered in the center of modern day Osaka, particularly at this Naniwa palace site that is now a vast park amidst an otherwise heavily urbanized landscape, where the sense of “this place was once scorned as country, it was once this abandoned, sprawling former palace site, but look how this cosmopolitan city has arisen about it!” echoes throughout.

I just love the ending: Miyabinikeri - How “capital-like” it has become! Not just because it’s one of my favorite ways to end a poem– -nikeri being a great way to convey exclamation, surprise, resignation… a whole range of things. But because I love the verb miyabu, which is what it is here. Later its linking form “miyabi” would become a noun meaning something like “refinement” - basically of the city, rather than of the country, something that is a very prominent theme in Heian literature, particularly Ise monogatari. But here, it is still a verb, the -bu suffix being a way of conveying “become x-ish” “become like x” “take on an air of x.” It’s just such a wonderful suffix. And I think it encapsulates the type of transformation that Umakai is taken aback over, that is, the becoming ALMOST capital-like, but not quite. It may be the site of the capital now, in Umakai’s present, but it is still Naniwa, and that is important. And we know that it may be capital-like now, but that come the following year, when the capital was relocated yet again to Shigaraki, and then later when it was dismantled for the building of Nagaoka, that it will return to being merely “Naniwa,” it will return to being “inaka” - its miyabi is impermanent, in other words. This makes the experience of its fleeting transformation into something capital-like the epitome of pathos, for we, although perhaps not Umakai, are aware of what’s to follow. But even in the poetic present - the law of rise and fall, the reality of the frantic capital hopping that Shōmu was engaged in at the time - were all possible reasons to believe that the Naniwa capital was not here to stay. And so Naniwa would continue to negotiate the boundary between “miyabi” and “inaka” - something that, in many ways, perhaps it still does.

Post link

1421 on Flickr.

Making my way through some of my favorite poems from Volume 2 of MYS, despite the fact that it’s perhaps not seasonally appropriate in this case:

明日香清御原宮御宇天皇代 [天渟 原瀛真人天皇謚曰天武天皇] / 天皇賜藤原夫人御歌一首

The age of the heavenly sovereign who reigned from the Kiyomihara Palace at Asuka (Ame no Nunahara Oki no Mahito no sumera mikoto; his posthumous name is Tenmu tennō)

One verse sent by the sovereign to his Fujiwara consort

吾里尓 大雪落有 大原乃 古尓之郷尓 落巻者後

我が里に大雪降れり大原の古りにし里に降らまくは後

wa ga sato ni/opoyuki pureri/opopara no/purinisi sato ni/puramaku pa noti

In my village, a great snow has fallen–but as for the fallen village at Ōhara, it has yet to fall.

藤原夫人奉和歌一首

One verse the Fujiwara consort offered in reply

吾岡之 於可美尓言而 令落 雪之摧之 彼所尓塵家武

我が岡のおかみに言ひて降らしめし雪のくだけしそこに散りけむ

wa ga woka no/okami ni ipite/purasimesi/yuki no kudakesi/soko ni tirikemu

On my hill, I told the Dragon God, and he made it fall - shattering the snow into many tiny pieces, he scattered them about here.

This seems like a very mundane exchange between the Tenmu and his consort, who in reality were only about a kilometer apart, the morning after a snow fall. And that is what it is - except it’s also so much more. That even such exchanges were conducted with the utmost decorum, creativity, and wit is what makes MYS poetry, and classical Japanese poetry in general, so wonderful. Tenmu’s verse is full of puns/associative word play: opoyuki/opopara, the “opo” in both cases meaning “great,” i.e. “great snow” and “great field.” We also have the repetition of “puru” meaning both “to fall” and “to become old/run down,” but in order to convey the pun in the case of “purinisi sato ni” I have translated it as “to the fallen village” - this in English maybe suggests a “downfall” and less of a gradual decay, which is the sense in Japanese, so I may have to rethink the best way to keep the pun relevant in translation… puns are what often make poems really interesting, and yet are probably the most difficult thing to convey well in translation (you pretty much always need a footnote). Tenmu has also loaded his verse up with “p” sounds in a way that just makes it delicious to enunciate, something I’m sure he was very aware of. In any case, Tenmu ends with what seems like it could be a question (he’s not where she is, so he doesn’t know, really, whether it has snowed or not, but he can probably guess that it has - which makes his ending statement almost necessarily a question “has it yet to fall?” because otherwise this makes no sense), but grammatically is not. “puramaku pa noti” is literally “its falling will be later” or something to that effect. In any case, the Fujiwara consort’s answer confirms that this is a rhetorical question of sorts, as she answers it, tongue-in-cheek, saying she brought about its falling where she is by offering prayers to the Dragon God, who was believed to control precipitation (snow and rain). Of course the snow had fallen – Ōhara is only one kilometer southeast of where the Kiyomihara palace site is thought to have been – but she cleverly attributes the snow having fallen there to her own prayers, and offers a powerful, almost frightening image of the deity “smashing” the snow and “scattering” it about. These sort of personified descriptions of the deity’s activity in a verse is something I’ve not seen elsewhere and what originally attracted me to this pair of verses. The consort’s verse in a way belongs to a sub-category of ritual verse that describes a prayer and then its content/after-effects (sometimes before they’ve happened in an anticipatory way to bring abut the desired after-effects, but this is not the case here), but she seems to be playing with the language of ritual to paint the reality of the snowfall in a more sacred, awe-inspiring light. We are not meant to believe she literally prayed to the dragon god of the hill for the snow. She simply casts it in this prayer-effect form in order to infuse the landscape with a supernatural power; in doing so, she conveys her cleverness, for she does not merely say “yes the snow has fallen and it is white” in an elevated style, as later poets might, but she re-imagines and re-shapes what she sees in a “grandiose” (taketakashi) way.

The other joy of these two poems which make them so much more than they appear on the surface is the layers of meaning provided by the man'yō gana transcription, with Tenmu’s poem using 落 for “puru” (which is common in MYS, I should say, but fits nicely with the sense of the verse) and 巻 “wrap up, roll up” for the future “mu” (mizenkei) + ku (nominalizer) in “puramaku,” which following immediately on 落for “furu” (to fall), suggests the piling up of snow, or even the enagement with it by packing it together as a snowball or the like. The consort’s verse is more clever, however, in its making use of 塵 (dust) for the verb “tiru,” which takes the “kudaku” (shatter, smash) to a whole new visual level, where the snowflakes are rendered almost imperceptibly small, the size of dust. This use of 塵 is a “gikun” - taking an established kun reading of a character and reapplying it in another context, where it is used for its phonetic and not its semantic value - but this stripping of meaning in the use of kun characters in this manner often involved the invoking of the nuance of the character’s semantic content, as it does in this case. Thus the transcription in MYS adds a whole new level of insight/interpretation, again emphasizing how texts had shifted from an oral to a written mode, where the visual perception of the verse was becoming an important (though still secondary to aural) means of apprehension.

I have paired this with one of my favorite photos of snow in my hometown - which was covered in more than 7 feet of snow this past winter and is only now emerging from underneath all that (I wasn’t there for that, so unfortunately don’t have a photo - even though that would probably indeed be the “greatest” of snowfalls… I doubt Tenmu meant quite that much with his 大). Living out in CA for the past several years, I do kind of miss the snow - there is a certain aesthetic value, for me at least, in the way it blankets the earth and covers over all of its imperfections, a great equalizer of sorts. Also, snow=water, and we could use some of that out here. I know people on the east coast and especially in MA probably never want to see a snowflake again, but believe me I think it’s a blessing, rather than a curse, to live somewhere the dragon god is willing to shatter the snow and spread it about. My prayers continually go unanswered in that regard.

Post link

IMG_0812 on Flickr.

勅穂積皇子遣近江志賀山寺時但馬皇女御作歌一首

One verse composed by Tajima no hime-miko when Hodzumi no miko was dispatched to a mountain temple at Shiga in Ōmi.

遺居 戀管不有者 追及武 道之阿廻尓 標結吾勢

後れ居て恋ひつつあらずは追ひ及かむ道の隈廻に標結へ我が背

okure yite/kopitutu arazu pa/opi sikamu/miti no kumami ni/shime yupe wa ga se

Rather than staying behind and being consumed by longing, I shall follow you–at each turn in your path, leave a trail for me, my love!

(MYS 1-115, Tajima no Hime-miko)

There is a series of three poems, 114-116, that deal with the illicit affair that apparently took place between Tajima no hime-miko, an imperial princess (daughter of Tenmu by Hikami no otome, a daughter of Fujiwara no Kamatari) , and Hozumi no Miko, an imperial prince and her half-brother with a different mother (it was the norm for members of the imperial family to marry their half-siblings of different mothers at this point). This was not illicit because of their shared father (shared fathers were ok, but not shared mothers, in sexual relationships between siblings; there is another tragic love story in MYS between two full siblings–Prince Karu and Princess Sotōri, perhaps I will post about this later), but because Tajima had previously been married to their elder brother, Takechi, Tenmu’s son by yet another woman (albeit of lower status, a woman of the Munakata family known as Amako no otome). (Side note: Tenmu had a lot of consorts, and therefore many children, which was partly the reason for a lot of bloodshed in the late seventh century as Jitō, one of Tenmu’s consorts and also daughter of his elder brother Tenchi whom he succeeded by force in 672, sought to keep succession in her line - when her son Kusakabe died prematurely, she herself seized power in order to ensure the throne would pass to her grandson, Kusakabe’s son Prince Karu/Emperor Monmu). It is not clear if this affair coming to light was the reason for Hozumi’s “exile” mentioned here - it is possible that it was considered bad form for Tajima to switch husbands, and so Hozumi was punished for this; it is also possible, according to another theory, that he was simply dispatched to Sūfukuji, a temple located in the old capital of Ōmi (modern day Ōtsu, Shiga prefecture) as an imperial representative. Such a command was tantamount to exile, especially for a member of the imperial clan, because of its distance from the capital, and thus Tajima’s distress at his being sent so far away. It seems likely that his being sent to Sūsenji had something to do with their relationship, since their parting is probably primarily of interest in this context, and its inclusion in MYS probably does have something to do with the interest, as well as the pathos, of it all. The previous poem (114) has Tajima, still in Takechi’s household, declaring to Hozumi that she will go to him, even if they are to incite rumors:

但馬皇女在高市皇子宮時思穂積皇子御作歌一首

One verse composed by Tajima no hime-miko, on longing for Hozumi no miko, when she was residing within Takechi no miko’s palace

秋田之 穂向乃所縁 異所縁 君尓因奈名 事痛有登母

秋の田の穂向きの寄れる片寄りに君に寄りなな言痛くありとも

aki no ta no/po muki no yoreru/kata yori ni/kimi ni yori na na/kochitaku ari tomo

Like the ears of rice that lean in one direction in the autumn fields, let me lean toward you–even if rumors are to arise.

This poem, in immediately preceding the one above, sets the stage that something is not quite “proper” about Tajima’s desire for Hozumi, and yet the pathos of the situation lies in the inability of either to control their emotions, and thus they say “damn it all” to rumors–however, despite this noble declaration, reality steps in between them, and he is, as we know, sent away. This first poem is amsuing in that it puns on Hozumi’s name by referring to the “ears of rice” that “lean” in one direction in the autumn fields, while the first character of Hozumi’s name is this same 穂 “ear of rice.” (The second character means “to pile up,” and it is possible to understand his name as “prince of the piled up rice ears,” if you want, but most names in this period are made up of “ate-ji” or characters chosen mostly for their correspondence to the sound of a person’s name, but also with an idea of “good meanings” in mind). However, I led the post with the second poem in the sequence because I think it is more evocative, in that it is not a mere declaration of love, but a counterfactual proposition that plays on the physical aspects of “going into exile” in order to convey the depths of longing of Tajima for Hozumi.

/okure yite/kopitutu (staying behind/longing and longing) is what we know she will be doing. She, in reality, cannot follow him–this seems to have been a purposeful separation. But rather than writhing in agony from the separation, she expresses her desire to follow him into exile, where he is traveling on a long road farther and farther from the capital - and she asks him to leave a trail for her. This is what particularly appealed to me about the verse - there is a real sense of a physical landscape where he is receding into the distance, but in order to be able to find a way to him, she asks that he leave signs for her along the path, so that she might follow. There is this deep pathos in the specificity offered by such an image - a concrete picture of a path along which she may travel to him, and yet we know she cannot follow. The reality of her inability to follow is contained in the final “my love” which seems to crystallize a desperation that pervades the rest of the poem. Ending with such an exclamation emphasizes the grieving woman, and provides a picture of her shouting after him, begging him to not go, begging him to leave a trail for her, she’ll meet him there.

I paired with this verse a photo of a path between peaks at Hōraisan, my favorite mountain that borders Biwako in Shiga - on the northeast side of the lake. I thought the tall grass meshed nicely with the “ho” (rice ears) image, while the sense of leaving a trail at the corners of the paths while traveling to the Shiga mountains seemed to fit overall with this photograph. This is one mountain I definitely want to revisit, should I have the chance - there’s an amazing waterfall on the way up, and beautiful views of the lake from the top.

Post link

IMG_1160 on Flickr.

I really should include the chōka for these two, but I find these two hanka quite powerful on their own:

樂浪之 思賀乃辛碕 雖幸有 大宮人之 船麻知兼津

楽浪の志賀の辛崎幸くあれど大宮人の舟待ちかねつ