#boulders

Stone

This is the Glen River on the lower slopes of Slieve Donard in the Mourne Mountains, Newcastle, Northern Ireland. It is a very beautiful wee place, but unfortunately as it is one of the more popular areas you can find quite a lot of trash and litter from inconsiderate people -__-

Post link

When the light is good in Florida. For more of my work, check out: Instagram.com/r4s & erickramirezphotography.com

Post link

Stuart, Florida coastline, if you didn’t know this existed in Florida, you need to get out more. More on my instagram: instagram.com/r4s

Post link

Rocks out of place

Why are these rocks out of place? They just do not fit the environment in which they are. The sea waves that moved the medium to coarse sand that is now the sandstone that surrounds these boulders, are not strong enough to move boulders. There is a huge contrast in mass between the sand and the boulder. So, the only explanation is they were placed here by some other means. For this reason, such rocks are called ‘dropstones’, as they were dropped/placed into their current position, rather than being transported along with the surrounding sediment.

One explanation how this could have happened, is the sea ice. During Permian (~300-250 million years ago) this region was under ice age conditions, with glaciers covering the continent from land to sea. So, whether it was glaciers sliding into the sea, or sea ice enveloping loose boulders around the coast and moving them off into the sea; it is impossible to say exactly. But, because ice floats on water, it provides a good candidate for a mechanism of moving these heavy boulders from the land to the sea bypassing the sea wave transport.

Ulladulla, Australia

Post link

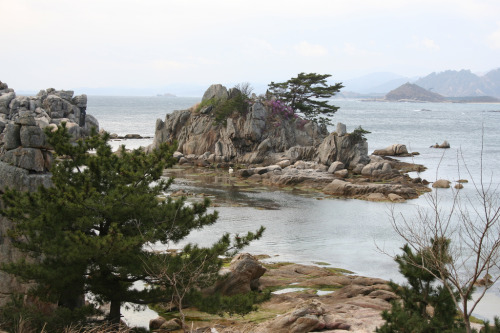

I searched my entire collection for a good photo for these. There was nothing quite right, but this will have to do.

有間皇子自傷結松枝歌二首

Arima no Miko, two verses composed bemoaning his own fate as he tied together two branches of pine

磐白乃 濱松之枝乎 引結 真幸有者 亦還見武

磐白の浜松が枝を引き結びま幸くあらばまた帰り見む

ipasiro no/pamamatu ga e wo/pikimusubi/masakiku araba/mata kaperi mimu

In Iwashiro - I tied two boughs of the shore pines; if I am truly fortunate, I will return to look upon them once more.

(MYS 2-141)

家有者 笥尓盛飯乎 草枕 旅尓之有者 椎之葉尓盛

家にあれば笥に盛る飯を草枕旅にしあれば椎の葉に盛る

ipe ni areba/ke ni moru ipi wo/kusamakura/tabi ni si areba/sipi no pa ni moru

When at home, I pile my rice in a bowl; since I am on a journey, I pile it atop leaves of chinquapin.

(MYS 2-142)

長忌寸意吉麻呂見結松哀咽歌二首

Naga no Imiki Okimaro, two verses composed in despair upon seeing the “tied pines”

磐代乃 <崖>之松枝 将結 人者反而 復将見鴨

磐代の岸の松が枝結びけむ人は帰りてまた見けむかも

ipasiro no/kisi no matu ga e/musubikemu/pito pa kaperite/mata mikemu kamo

That person who is said to have tied together the shore pines at Iwashiro - did he ever return to look upon them once more?

(MYS 2-143)

磐代之 野中尓立有 結松 情毛不解 古所念[未詳]

磐代の野中に立てる結び松心も解けずいにしへ思ほゆ[未詳]

ipasiro no/nonaka ni tateru/musubi matu/kokoro mo tokezu/inisipe omopoyu

The “tied pines” that stand in the field at Iwashiro - like them, my heart does not unknot as a time long ago comes to mind. (author unclear)

(MYS 2-144)

山上臣憶良追和歌一首

Yamanoue no Okura, one verse composed as a follow-up

鳥翔成 有我欲比管 見良目杼母 人社不知 松者知良武

鳥翔成あり通ひつつ見らめども人こそ知らね松は知るらむ

tubasa nasu/arikayopitutu/miramedomo/pito koso sirane/matu pa siruramu

Having become winged, you surely continue to look upon them as you fly about the sky; people may not know this, but the pines surely do.

(MYS 2-145)

大寶元年辛丑幸于紀伊國時<見>結松歌一首 [柿本朝臣人麻呂歌集中出也]

In the first year of Taihō (younger brother of metal, ox), on the occassion royal outing to the land of Ki, one verse composed upon seeing the “tied pines” (This appears in the Kakinomoto no Asomi Hitomaro collection)

後将見跡 君之結有 磐代乃 子松之宇礼乎 又将見香聞

後見むと君が結べる磐代の小松がうれをまた見けむかも

noti mimu to/kimi ga musuberu/ipasiro

Thinking he might look upon them again, my lord tied these together: the small pines of Iwashiro, did he ever again look upon their boughs?

(MYS 2-146)

These six verses kick off the “banka” (elegy; or “coffin-pulling” verse) section of the second book of Man’yōshū, although the compiler admits they are not very banka-like in a note that follows Okura’s poem:

右件歌等雖不挽柩之時所作<准>擬歌意 故以載于挽歌類焉

The poems to the right were not composed on the occassion of “pulling the coffin”; however, the content of these verses matches up, and so for that reason they have been put into the category of “banka.”

This suggests that the category of “banka” was still relatively new and fluid: the first two of these verses are supposed to be by Arima himself! How could he have possibly composed his own elegy? The verses by Okimaro and Okura that follow seem to fit the category of “banka” a bit better, as they lament Arima’s unfortunate fate, but were likely composed on the outing to Ki in 701 mentioned in the headnote to the final verse, and thus some forty years after Arima’s demise. The section places all these verses under the reign of Saimei, but again that only works in terms of “content.” However, the story of Arima’s “tied pines” seems to have been a famous tragedy at this point, and so having a section on it in the volume is fitting, and perhaps “banka” was chosen to tell this story, for lack of a better available categorization.

Prince Arima was the son of the sovereign Kōtoku, brother of Saimei and both her successor (as Kōgyoku) and predecessor (as Saimei). He lived just eighteen years, executed for having become involved in a plot to manipulate succession in his favor, egged on by Soga no Akae, the grandson of Soga no Umako (who was killed by Tenji, then Prince Naka no Ōe). Akae later betrayed him to Naka no Ōe, leading to the prince’s capture in the province of Ki. He pleaded that he had no knowledge of a plot, and such was all Akae’s doing; he thought he might be safe, but alas, he was executed in Ki soon thereafter. The first two poems are supposedly from the brief period between the time of his capture and his execution, and are thus imbued with a deep sense of pathos as the prince is aware he will likely never see the “tied pines” again.

The first poem describes the act of tying the pines together at Iwashiro, which becomes a symbol of the prince’s tragic fate for the following poems. It has the structure of a ritual-prayer verse, as it seems to be imploring the pines to allow him to return and look upon them by ensuring his safety. This is a typical prayer-structure: describing the act of the prayer, then its content; however, the content is never relayed as a direct address, but states the desired outcome in either present or future. The act of tying the pines together also undoubtedly has ritual significance, and so there can be no doubt that this verse was meant to evoke the sympathies of the local deities to ensure his safety. (ma-sakiku, which I have translated above as “truly fortunate,” really implies fortunate in the sense of safe/without harm). If we read this as having been composed in the mid-seventh century (some scholars argue the poems were later attributed/proxy-composed for Arima), then the ritualistic understanding is most appropriate. However, by the time of Okimaro and Okura, Arima’s poem is re-interpreted as being imbued with pathos, with Arima’s awareness of his impending execution and his desire to leave a physical katami (memento) of his presence on the landscape, a landscape which he will never see again. The ritual meaning may not have been entirely lost, but had likely been caught up in the lore of the prince’s tragic death, such that it was now more about that lingering symbol of him, while he himself was long gone from the earth, than it was about his final plea for divine mercy.

The second verse attributed to Arima at first glance seems considerably less powerful and that it almost doesn’t fit here with the other five, but actually carries over many similar sentiments from the previous. It is perhaps, in contrast with the previous, a lyric expression of the prince’s awareness of his inability to return to his former life, and his impending end, in contrast to the plea in the previous verse (one might also argue, however, that the act of making such a plea is an expression of his awareness of the inevitability of his death). He had been accustomed to a life of rice in a bowl - a proper container - but now he has been cast out of his former position, his former life, and finds himself eating rice atop “chinquapin” (a type of beech tree) leaves. He says this is “because [he is] on a journey,” but in the context we know this is no mere “journey,” but something with considerable more finality–there is no possibility of return. We are thus afforded an image of a prince partaking of his final meal, out on the frontier, away from everything he once knew. We sense harsh winds blowing in from the ocean, through the pines which he tied together, as he awaits the inevitable. HIs last meal in this rustic, harsh setting is atop beech leaves. Is he still a prince in this poem? Perhaps, but one who has surely lost everything at this point.

Arima’s two verses are thus interesting “banka” in that they look forward to death with despair and resignation (with perhaps a dash of hope in the plea, but again it may be ironic), rather than look back from death in anguish and lament. The perspective of the one “who will die” is undoubtedly unique. I can’t think of any other examples quite like this. It is the awareness of the impending end, and its inevitability, that plays further into the pathos of remembering Arima in Okimaro and Okura’s poems. Arima’s poems offer his respondents of a later age a glimpse into his mind as he looked forward to death, connected with a concrete image of the “tied pines,” to which they too, presumably have access when visiting the shores of Ki, which then prompts them to remember and compose. They know the pines were tied together as a ritual act, perhaps, but also as one that would symbolize hope against hope that he might see them again: it is the fact that this hope was dashed that is so incredibly aware (pathos), and which becomes the focus of Okimaro and Okura’s verses.

The first Okimaro poem does little more than rephrase Arima’s first verse in the third person, but as a response to Arima’s verse from someone aware of the outcome, it is strikingly powerful. Okimaro asks if that person who tied together the pines ever did return, and it is the implicit knowledge that he did not that moves one to the verge of tears. The second poem (which, for some reason, is followed by a note that the author is unknown, despite it being attributed to Okimaro in the headnote…) is more about the speaker, in his moment, reflecting on the past as he sees the pines still tied together in the present. Like the knotted pines, his heart is “knotted” as he remembers Arima’s tragic fate. The second poem is thus more explicitly a lyric response to the sight of the “tied pines” and their associated lore, by the poet himself in the present moment, while the first focuses more on the tragedy of the past.

Okura’s poem does something quite different: it attempts to find consolation in the idea that Arima’s spirit must have transformed into a bird (an old belief attested in Kojiki), and thus could fly about the sky and look upon the pines from there - and while the people of the world regard Arima’s inability to return to the pines and look upon them a tragedy, the pines themselves know Arima has in fact returned, as a spirit. Okura is indeed a unique poet, and this is an example of how his perspective at times utterly deviates from the standard: he is one of the few poets that I am aware of to seek comfort in the notion of an afterlife, a state beyond death that allows for the fulfillment of the otherwise tragically unfulfilled promises of life. Most banka, as with Okimaro’s, simply lament and bemoan that unfulfillment, recalling it in the present and being moved to tears, but rarely seeking any relief from that. This is indeed something I’d like to look more into…

The final poem I’ve included here, which rounds out the Arima section, is said to be taken from the Hitomaro kashū, but that does not necessarily mean it is by Hitomaro. It is in many ways similar to Okimaro’s first verse, in that it rephrases in the third person the first, more ritualistic of Arima’s verses. It does begin with “nochi,” however, which is a quite powerful word (when compared with kaeru “return,” I would argue), because we know there was no “nochi.” For Arima, there was only the now, there was never a “later,” and our knowledge of that, along with the poet’s of course, is what makes this poem a powerful response to seeing the pines in the present (from Arima’s perspective, “nochi”). Others see them “nochi” and recall Arima - but Arima himself never had such an opportunity to look upon them again.

Okura’s poem is really the stand out in the bunch. I really enjoy him. If I had the time, I would have a blog solely about him.

I have paired this with a photo from my trip to Kǔmgangsan, North Korea, in April 2006, mostly because it was one of the few photos in my collection that featured a pine on the shore, and I also enjoy the large boulders as evocative of the name “Iwashiro.” Unfortunately, none of the pines are “tied together” - I am now going to be on the look out for such things, however, and perhaps can provide a better photo at a later date. If you plug 結び松 into google images, however, you can get an idea of what it likely looked like.

Well, that might be enough aware for the day.

Post link

#Repost @bia.lan with @repostapp.

・・・

#penguins #penguin #nature #boulders #simonstown #sealife #threesomes #cape_town #capetown #birds# #flightlessbird #southafrica

可愛いヒナちゃんたち

Post link

⛰

Mon Repos or Monrepos is an extensive English landscape park in the northern part of the rocky island of Linnasaari outside Vyborg, Russia. The park lies along the shoreline of the Zashchitnaya inlet of the Vyborg Bay and occupies about 180 hectares (440 acres) of land.

The seaside park is strewn with glacially deposited boulders, scenic cliffs and wooden pavilions. It is considered a landmark in the evolution of the Romantic taste for landscape gardening.

Photos byLina Groza

Post link