#normalheart-history

Have you ever had a medical professional describe your care as a collaboration between you and your doctors? Has a family member with a terminal illness been given expedited access to experimental treatments? Then your experience of medical care in America has been profoundly shaped by the AIDS crisis, and by ACT UP.

ACT UP was not the first or the only group involved in reforming the way medical research and medical care were done. Feminist health movements in the 1970s were an important forerunner, and feminist activism continued to be critical: in 1987, the Congressional Women’s Caucus got the National Institutes for Health (NIH) to change rules that kept women of child-bearing age out of all federally-funded medical research. The disability rights movement has been part of changing the conversation as well.

But AIDS activists, and particularly ACT UP, radically changed the face of medicine as we know it. By engaging with researchers, pharmaceutical companies, regulators, and doctors at all stages of the drug and treatment pipeline, by educating themselves on and challenging the orthodoxies of medical science, and by using the sheer numbers and anger of their members to their advantage, they created radically new relationships between patients and the medical establishment.

The FDA approved rules that allowed terminally ill patients expanded access to a drug undergoing phase II or III trials (or in extraordinary cases even earlier) if it potentially represented a safer or better alternative to other treatments. They also created a “parallel track” system to get potentially lifesaving drugs to patients who could not take part in clinical trials. The FDA’s official consulting with patient representatives as part of approving new treatments began with AIDS, but quickly expanded to include a range of cancers as well.

Gay urban men with AIDS, already connected through their pre-existing community, taught themselves and each other about the disease, and challenged their doctors about their care. The extent to which patients sometimes knew more about the disease than their doctors meant that the traditional balance of power in the medical relationship shifted.

By 1988, there was an entire infrastructure encompassing treatment publications and buyers clubs, advocacy groups and grassroots activists — a firm foundation that could then support widespread dissemination of medical knowledge. And by this point, these organizations’ knowledge about AIDS often exceeded that of the average practicing physician. “When we first started out there were maybe three physicians in the metropolitan New York area who would even give us a simple nod of the head,” said the director of a New York City buyers club in 1988. “Now, every day, the phone rings ten times, and there’s a physician on the other end wanting advice. [From] me! I’m trained as an opera singer!” (source)

It’s become a truism now that patients should learn about their conditions and their care, but it was largely people with AIDS who, in their numbers and their vehemence, shook up the medical establishment’s perspective on the doctor/patient relationship, and the ingrained belief that doctor knows best.

Thom Gunn was an openly gay poet in San Francisco. Although he never contracted HIV, he wrote the most famous volume of poetry about living through the epidemic. The title poem, “The Man With Night Sweats,” is even quoted in Emily Nussbaum’s review of the HBO version of The Normal Heart in The New Yorker. It’s short enough to reprint here in full.

The Man With Night Sweats

I wake up cold, I who

Prospered through dreams of heat

Wake to their residue,

Sweat, and a clinging sheet.

My flesh was its own shield:

Where it was gashed, it healed.

I grew as I explored

The body I could trust

Even while I adored

The risk that made robust,

A world of wonders in

Each challenge to the skin.

I cannot but be sorry

The given shield was cracked,

My mind reduced to hurry,

My flesh reduced and wrecked.

I have to change the bed,

But catch myself instead

Stopped upright where I am

Hugging my body to me

As if to shield it from

The pains that will go through me,

As if hands were enough

To hold an avalanche off.

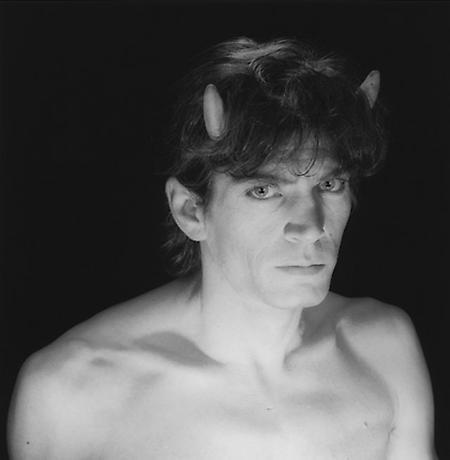

(Self Portrait, 1985)

Robert Mapplethorpe was born in 1946 in Queens, New York. He studied drawing, painting, and sculpture at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, and after college lived in the Chelsea Hotel with his close friend Patti Smith: she’s written about those years in her award-winning memoir, Just Kids.

(More images and history under the cut; all SFW.)

Mapplethorpe moved into photography in the 1970s, creating iconic album cover art for Patti Smith and Television. As the 1970s continued, he became increasingly interested in photographing the local S&M scene. As the biography on the Mapplethorpe Foundation site puts it,

The resulting photographs are shocking for their content and remarkable for their technical and formal mastery. Mapplethorpe told ARTnews in late 1988, “I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.”

Those were not his only subjects: among other photos, he did a series in collaboration with Lisa Lyon, the first World Women’s Bodybuilding Champion. and he photographed many other artists, including this photo I’ve always loved of sculptor Louise Bourgeois holding one of her own works (possibly NSFW). His works are classically, almost austerely beautiful, and highly stylized. In 1986, his exhibit of eroticized photos of black men created controversy when it was accused of being exploitative and dehumanizing in its stylized depictions.

In the last years of his life, Mapplethorpe’s work became more popular, and there were three exhibits of his work in 1988. Although it was widely known in the art world that Mapplethorpe had been diagnosed with AIDS in 1986, the New York Times review of his Whitney Museum exhibit called it a “mid-career retrospective,” ignoring the disease.

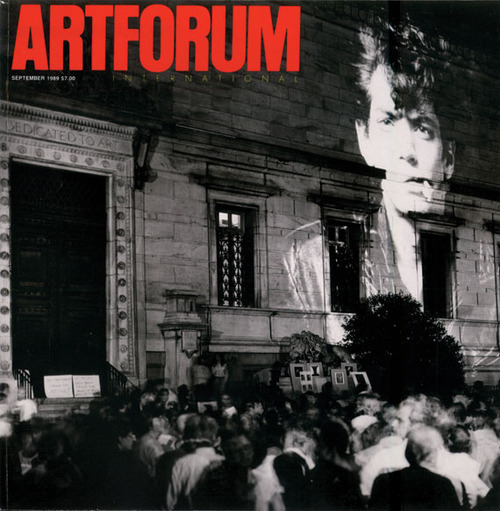

One of those 1988 exhibits, “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment,” traveled from Philadelphia to Chicago, and was then supposed to be shown at the Corcoran Gallery in DC. Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC), an extremely conservative and vocal Republican leader, learned that the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) had given $30,000 to the Philadelphia museum towards the cost of curating the show, and he got 100 members of the US Congress to write a letter of complaint to the NEA about subsidizing materials of “a morally repugnant nature.” The Corcoran, worried about its own NEA funding, pulled out of the show.

As a result, the Corcoran lost $1.5 million in promised bequests, several artists forbade their work from being shown there, and membership dropped by 10%. The exhibit – which kept the explicit works in a separate age-restricted gallery – was taken in instead by the Washington Project for the Arts, which had over 35,000 visitors in three weeks – still a record there. A large protest outside the Corcoran, uniting free speech advocates, artists, and gay rights activists, projected works from the show onto the Corcoran’s walls.

The exhibit would create controversy again in 1990, when the curator of Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center was charged with obscenity for staging the exhibit.

The last image you saw when leaving “The Perfect Moment” was Mapplethorpe’s final self-portrait, taken just months before his death.

(Self-Portrait, 1988)

In this late photograph, Mapplethorpe is no longer playing a role, as he did in so many of his earlier self-portraits. It was taken a few months before he died from an AIDS-related illness in 1989. In it he faces straight ahead, as if he were looking death in the face. The skull-headed cane that he holds in his right hand reinforces this reading. Mapplethorpe is wearing black, so that his head floats free, disembodied, as if he were already half-way to death. Mapplethorpe even photographs his head very slightly out of focus (compared with his hand) to suggest his gradual fading away.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was a Cuban-born American artist, working primarily in minimalist installations and sculptures. Many of his best-known works were created in memory of his partner, Ross Laycock, who also died of AIDS.

Untitled (1991) is a billboard that was originally installed in twelve locations throughout New York City. This photo is from a MoMA re-installation in 2012.

The image of an empty, slept-in bed, created the same year as Laycock’s death, is an act of mourning:

When people ask me, “Who is your public?” I say honestly, without skipping a beat, “Ross.” The public was Ross. The rest of the people just come to the work.“ - ArtPress Interview

But it is also an assertion that their private lives are worthy of public consideration, claiming a dignity for their intimacy that years of hysteria around the epidemic had taken away.

Even more moving is "Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” 1991, which is on display in the Art Institute of Chicago.

To quote the catalogue from a recent Brooklyn Museum show the piece was included in:

González-Torres created a spill of candies that approximated Ross’s weight (175 lbs.) when he was healthy. Viewers are invited to take away a candy until the mound gradually disappears; it is then replenished, and the cycle of life and death continues. While González-Torres wanted the viewer/participant to partake of the sweetness of his own relationship with Ross, the candy spill also works as an act of communion. More darkly, the steadily diminishing pile of cheerfully wrapped candies shows the dissolution of the gay community, as society ignored the AIDS epidemic. In the moment that the candy dissolves in the viewer’s mouth, the participant also receives a shock of recognition at his or her complicity in Ross’s demise.

In 1995, while he was still alive, Gonzalez-Torres was rejected from the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale in part because his work was considered too political. In 2007, he was chosen to represent the US at the Biennale, with some of his initial concepts for the 1995 show included: he was only the second posthumous representative the US has ever had at this important international art event.

On November 7, 1991, Magic Johnson, superstar basketball player, held a press conference to announce that he was HIV-positive and would be retiring from basketball immediately. Some of the sports writers in the audience wept openly at the news.

It was the top story on the national news broadcasts that night, and Tom Brokaw sounds like he’s reporting on a sudden death:

The news is so shocking and so unexpected, it is difficult to absorb it even as we report it. Magic Johnson has tested positive for the HIV virus: that’s the first step to AIDS. Magic Johnson, basketball superstar so beloved, so well-known, that his first name was all he needed well beyond the world of sports.

(emphasis ours.) At the time, there were far fewer treatment options, and many people still believed HIV infection meant an automatic death sentence. But even as late as 1991, many people didn’t understand that the risk of infection came from what you did, not who you were. To quote a Time retrospective on the 20th anniversary of Johnson’s announcement:

“It made people notice, for the first time, that you can get infected with HIV without being gay, without being a drug user, without being a sex worker,” says Kevin Frost, CEO of amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research. “A lot of people took notice, and that changed the perception of how people got infected, and who was at risk.”

The next day, there were four times as many calls as usual to the National AIDS hotline, and closer to Johnson’s home in LA, it was more like six times as many. The New York Times devoted 300 column inches to the story over the following three days, which by our back of the envelope calculations comes out to roughly four solid pages of text. That a healthy, heterosexual, black athlete was now HIV positive upset the image people had of the disease. It could even be argued that the announcement, coming just months before the start of clinical trials on combination antiretroviral therapy, marks the end of the early AIDS era.

Johnson’s announcement was met with outpourings of both affection and fear. In 1992, fans voted him on to the NBA All-Star team, but several of his former teammates said that he shouldn’t play, while others openly worried about the risk of infection if Johnson were wounded on the court. Johnson would go on to be voted the game’s MVP and also be part of the men’s Olympic “dream team” in 1992.

Johnson is still healthy, and the Magic Johnson Foundation, founded in the wake of his announcement, is still an active philanthropic organization, though its mission has grown. As the Foundation’s site says,

MJF was created to fight HIV/AIDS through grantmaking. Twenty-two years after its formation, the organization has evolved to address other powerful epidemics in urban communities, which include the lack of educational opportunity and the absence of empowerment.

Linda Laubenstein, 45, Physician And Leader in Detection of AIDS

Published: August 17, 1992

Her family said an autopsy was pending. She suffered from severe asthma and weakness from childhood polio, an illness that required three major operations and left her a paraplegic at the age of 5.

“She is incredibly important in the history of AIDS, a genuine pioneer and a real fighter for what she believed,” said Larry Kramer, an author and a leader in AIDS causes.

Dr. Laubenstein inspired the character of Dr. Emma Brookner, a principal role in Mr. Kramer’s play on acquired immune deficiency syndrome, “The Normal Heart.” He said an agreement was near on the production of a movie version by Barbra Streisand, with Ms. Streisand playing the Laubenstein-Brookner part.

Dr. Laubenstein and Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien wrote the first paper to be published in a medical journal on the alarming appearance of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a previously rare disease of lesions of the skin and other tissues. Most of the cases were in young gay men suffering a puzzling collapse of the immune system.

Recalling one of the first cases, she described a 33-year-old man with two purple spots behind his ears. Initially he responded to the cancer drugs she prescribed. But 18 months later he was dead, his body covered with 75 lesions.

Many more cases followed. By May 1982, she had seen 62 patients with AIDS – a fourth of the national total recorded at the time. She said then that “this problem certainly is not going away.”

Her father, George Laubenstein, said yesterday, “She told us from the very beginning that this is going to be a terrible epidemic.”

Dr. Laubenstein’s private practice grew to be predominantly AIDS cases. She and Dr. Freidman-Kien arranged the first full-scale medical conference on AIDS, at New York University in 1983. She also help to found the Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research Fund in 1983.

Jobs in Office Services

In 1989, she and Dr. Greene founded Multitasking, a nonprofit organization selling office services to other businesses and employing people with AIDS as the workers. Her concern was that AIDS patients often lost their jobs and that work was vital to emotional and physical health as well as for financial support.

Dr. Laubenstein was outspoken about what she said was the neglect by government and society in fighting AIDS. Some of her views were controversial among gay groups, particularly her belief that bathhouses should be shut down to discourage unsafe sex.

Born in Boston, she grew up in Barrington, R.I. She graduated from Barnard College and New York University Medical School. Her specialties were hematology and oncology, and she was a clinical professor at the New York University Medical Center.

Surviving are her parents, George and Priscilla of Harwich Port, Mass., and a brother, Peter of Melvin Village, N.H.

The New York Times obituary for Linda Laubenstein, the inspiration for the doctor in The Normal Heart.

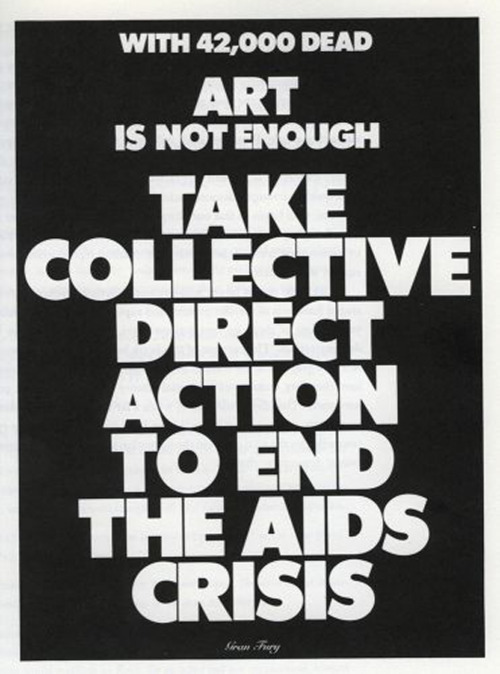

After most performances of the 2011 Broadway run of The Normal Heart, you could find Larry Kramer outside the theater, handing out this leaflet.

Post link

HBO’s adaptation of The Normal Heart airs tonight. We’ll be watching, and we hope you will be too.

We’ve collected these resources over the last week—with lots of help—in hopes of providing more context to the story of the early AIDS epidemic than what we’ll see on the screen.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Please, help us spread the word about normalheart-history by reblogging this and our other posts.

Encourage anyone who’s watching the movie to ask us anything about the people and stories portrayed in the film.

And submit your own story about the epidemic so we can post that, too.

Post link